March 31, 2019

William Josie is watching dramatic changes in weather and animal behaviour unfold in Yukon’s most northern community of Old Crow.

Josie, the executive director of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, thinks much of the shift has to do with the effects of climate change.

He and his family spend a lot of time hunting and trapping at their camp at the mouth of the Driftwood River, about 85 kilometres up the Porcupine River.

“The biggest change I’ve seen in the past 20 years is the weather. We seem to be getting warmer winters, we have open water in lakes and rivers, longer and wet summers," says Josie.

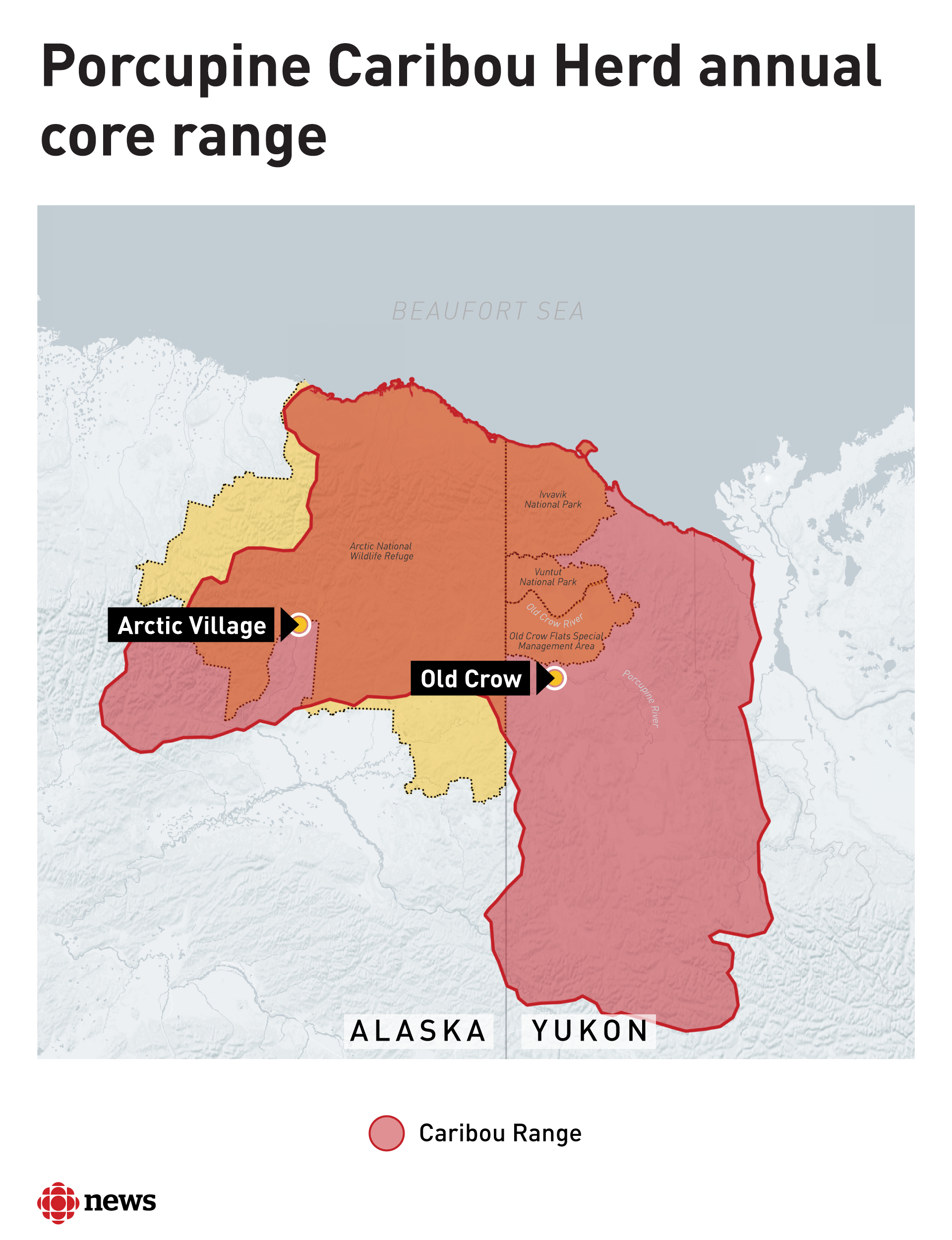

He says the caribou are now staying north of the Porcupine River during the fall, and in winter the majority stay in Arctic Village in Alaska.

Last fall, Josie says the herd stayed in the Vuntut National Park and special management areas, about 85 kilometers north of where they usually are. That meant hunters had to go up the Old Crow River to find them.

The changes Josie is seeing suggest a shift in animals’ traditional habitat, as weather patterns change throughout the territory.

He thinks caribou are moving farther north to escape the effects of climate change, specifically an increase in wet weather.

Josie says there’s a lot more rain and it lasts longer, from the summer to well into the fall. So the ground is freezing up, virtually sealing off lichens, an important food source for caribou in winter.

“There is a bigger moose harvest in Old Crow because it’s harder to get caribou in the fall," said Josie.

Josie says that shrubs are now growing north of the treeline and moose are following the food source farther north, so there are more of them to hunt around the community.

Mark O’Donoghue, a biologist with Yukon’s Fish and Wildlife branch, says this increased growth of shrubs due to climate change is attracting moose into what used to be primarily caribou habitat.

“The increase in shrub growth northwards into the tundra and higher up mountains is well-documented as temperatures warm.”

O’Donoghue points out that a longer growing season stimulates more growth, and shrubs can then overtake other plants.

He also warns that human disturbances — things like forestry, or cutting seismic lines and roads for natural gas exploration — also help create shrubby conditions and drive caribou farther north.

“Definitely if you get some real rain during the winter time, that makes it hard for caribou to get at their food,” O’Donoghue said.

“They want the lichens in the ground and that can make them less accessible.

“Certainly in the far north that has been a cause of some die-offs of caribou when they have a lot of rain and they just can’t get food.”

'If they encounter some cold weather in the spring then they just die of hypothermia or pneumonia.'

And there are other threats to their food source — O’Donoghue says biologists are also watching the impacts of a changing fire regime due to climate change.

“If we end up with more frequent or intense fires, these would likely have side effects on caribou, which require lichens for winter food — these take at least 40 to 50 years to develop.”

Deadly for moose

Indigenous elder Chuck Hume lives in the southwestern part of the territory in the small community of Haines Junction.

Hume was born in the bush on the traditional territory of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations and has spent much of his life out on the land as a hunter, trapper, outfitter and park warden at Kluane National Park and Reserve.

“It’s a late spring now and it runs right into May, June, it stays cold and then our falls are running right into late December,” said Hume. “So it’s a pretty good indication there is a shift that’s happening.”

Hume says the late spring is killing off moose calves in the area.

“The weather is very critical when they’re born. If they encounter some cold weather in the spring then they just die of hypothermia or pneumonia, you know they are wet when they come out and it’s cold.”

Hume’s suspicion that the moose calf population is down significantly was confirmed when he participated in an aerial moose count with Yukon Fish and Wildlife officials in Kluane National Park last November.

The survey showed that while adult moose populations are increasing, there aren't as many calves. Usually staff will see 35 calves per 100 cows, but this year, there were only nine or 10.

According to a recent report from the United Nations, even if the Paris Agreement goals to cut emissions and curb global warming are met, “Arctic winter temperatures are expected to increase three to five degrees Celsius by 2050, unleashing sea level rises worldwide.”

On top of that, and perhaps more devastating for wildlife, rapidly thawing permafrost could accelerate climate change even more.

There’s also the potential of oil and gas development of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) by the Trump administration.

ANWR is an integral breeding ground for the Porcupine caribou herd. First Nations and environmental groups believe any kind of development would have catastrophic consequences for the herd.

Strong caribou numbers

Despite all of this, the Yukon currently has a very strong caribou population.

While many caribou herds in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are at record low numbers, O’Donoghue says the Porcupine caribou herd numbers are at an all-time high. According to the Yukon government, the most recent survey in 2017 shows the herd to be well over 200,000 animals.

William Josie remains optimistic.

“They’re going to have to adapt and that’s what they are doing and they’re staying up there where they still have food, it’s cold and they don’t have to go very far to calf.”

He says now it’s the people who are going to have to change.

“We may have to build a meat camp somewhere [farther north] to supply our community down the road, but we’re going to adapt, believe me.”