November 5, 2018

Glyn Williams-Jones was lying on his belly on wet rocks and ice, uncertain whether the ground beneath him might give way or the thick ice shelf overhead would break off and fall onto him.

He was peering into the abyss of an ice cave and could not have been happier.

"This is spectacular," he said with a broad smile on his face. "It's not often you get to see underneath the bottom of a glacier."

The glacier sits on top of the last volcano to explode on Canadian soil: Mount Meager, northwest of Whistler, B.C. But the fact that it erupted just over 2,400 years ago does not mean it's past its potential to blow again. That's just the blink of an eye in geological terms.

The combination of the volcano and its shrinking glacier has drawn Williams-Jones. He is a volcanologist from Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C., and brought a team to, as he said, "read the signals, the body language" of the mountain in hopes of knowing when the next eruption will happen.

"This big, massive mountain is rotten."

Global warming, said Williams-Jones, is increasing the chances of a landslide or an eruption.

Mount Meager is part of B.C.'s coastal mountain range. A helicopter journey there offers stunning views of peaks and fields of ice dropping down into valleys, rivers and alpine lakes. For the rich, it can be a playground: guides fly in heli-skiers, couples propose marriage against dramatic backdrops and, according to one guide, a party of several dozen people once had a catered lunch on the mountaintop — complete with a DJ and a tequila bar carved out of the ice.

But Williams-Jones's reason for coming here is more sobering.

Mount Meager, he believes, is cracking, collapsing and potentially threatening the safety of people who live in the region.

Two years ago, a helicopter pilot spotted something as he flew over the mountain. There were three holes in the glacier and something was belching out of them.

Williams-Jones heard of the discovery and confirmed that the holes were fumaroles — vents that spew a mix of steam and toxic gas from the underlying volcano.

They had emerged, Williams-Jones said, because the ice is shrinking as a result of climate change.

Sleeping giant

When his team's helicopter landed on the glacier that day in September, the smell of rotten eggs filled the air. It was hydrogen sulfide, mixed with carbon dioxide and steam from below, which produced a ghostly churn of mist.

In the open air, the smell is unpleasant, and the gas may cause headaches. The greater danger is getting trapped in an enclosed space — a crevice or crack — where concentrations of the gas can knock a person unconscious and, at worst, kill them.

Williams-Jones hiked up to the edge of a fumarole with a guide, carefully poking the ice to avoid falling into a crevice. Tethered to posts driven deep into the glacier, he set up two boxes near the edge to record the gas levels.

"This big, massive mountain is rotten," he said, standing at the edge of one of the fumaroles.

"It's been growing for two million years, and over that time, we've had all of these gases and acid fluids coming through the rock and, slowly but surely, changing into weaker rock. And that weaker rock fails."

The team is researching not only the gases and the expansion of the fumaroles, it is also measuring the speed of the glacier's retreat and the potential for a landslide, which could trigger an eruption.

All of those factors combine to create instability and uncertainty about when disaster might strike.

Williams-Jones is certain Mount Meager will erupt again. He just cannot say when.

"It is like a great, sleeping giant and in some ways, it is more dangerous as things can build up," he said.

Mount Meager is one of a string of volcanoes reaching up North America's west coast between Northern California and Alaska. They include Mount St. Helens in Washington state, the site of a deadly eruption in 1980. Fifty-seven people died when the north face of the mountain collapsed, triggering an eruption. In its intensity, it mirrored the last volcanic eruption on Mount Meager so long ago.

Using this volcano as a laboratory is a homecoming of sorts for the Canadian-born Williams-Jones. While completing his master of science degree, he worked on a volcano in Costa Rica.

"It was erupting every half hour," he said. "It was great."

Williams-Jones has also worked in Nicaragua and on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. He only began focusing on Canadian volcanoes about six years ago.

One of Canada's leading authorities on Earth sciences and natural hazards, John Clague, described Williams-Jones as "very enthusiastic and very committed."

"He is achieving an international reputation for being a leader in this field, but it is really driven by a passion to better understand volcanoes so you can reduce the risk they pose," said Clague, a professor emeritus at Simon Fraser University.

"It is very likely this slope will fail very soon."

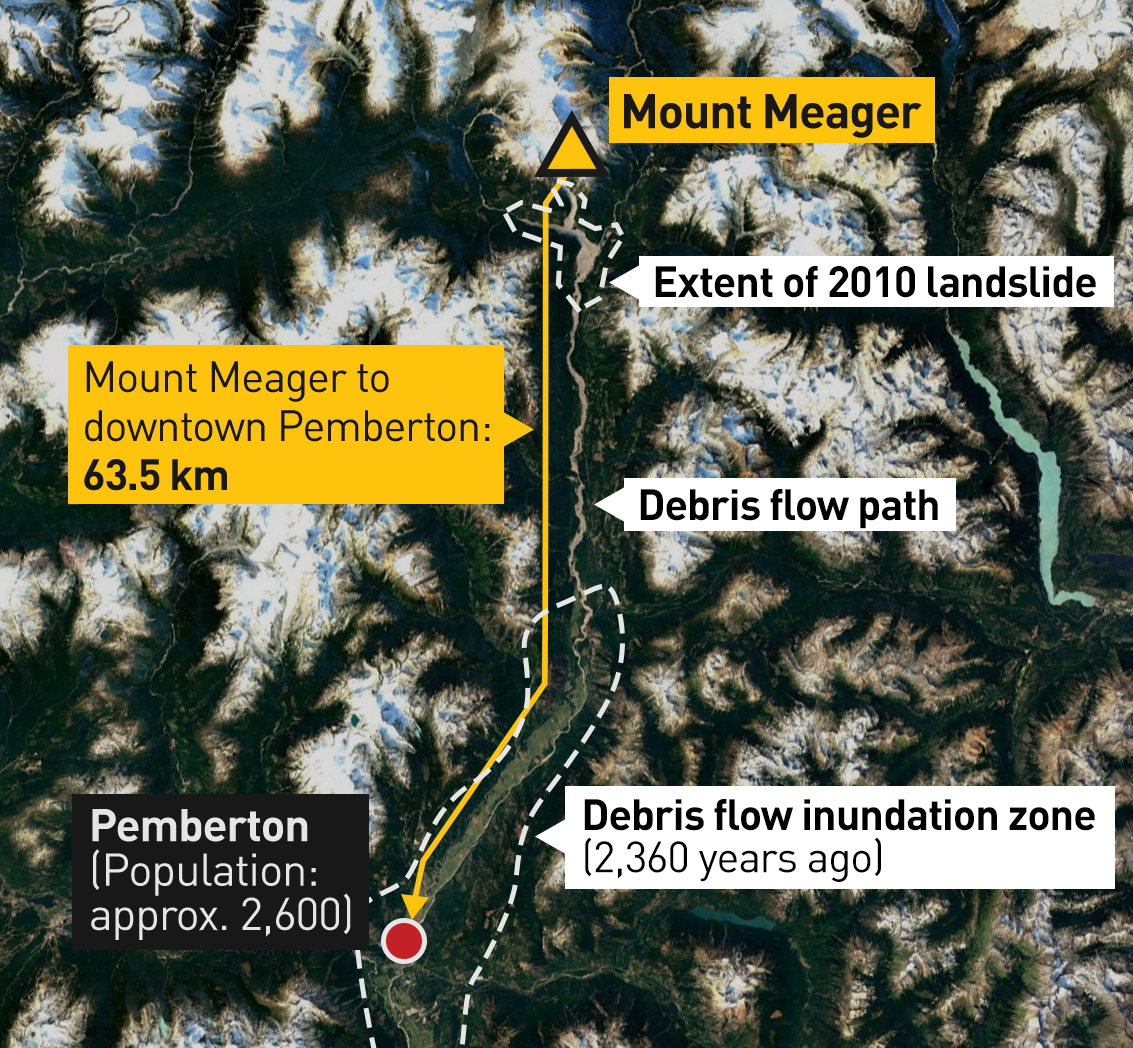

In this case, it is the people who live in the nearby Pemberton Valley who may be in harm's way. There are about 5,300 residents spread through three communities living within about 60 kilometres of the mountain.

The risk is not immediate, but an eruption could be devastating. The more immediate concern is potential landslides.

Gioachino Roberti, a PhD student on Williams-Jones's team has studied the cracks on the massive rock face of the mountain and has deemed the risk to life "unacceptable."

As he stood on the glacier, Roberti swept his left arm upward, pointing to a nearby peak.

"It is very likely this slope will fail very soon," he said.

There is a visible crack in the rock, and the flank is moving a few centimetres each month, he said.

Roberti does not have to imagine the impact of a slide. He simply has to look back at what happened on this mountain eight years ago.

Nearly 50 million cubic metres of material crashed down the mountainside in 2010. The debris travelled 13 kilometres — destroying bridges, roads and equipment. Seismic waves were felt as far away as Alaska and Washington state.

"This one is about 10 times bigger," said Roberti of the next potential slide. "It could travel 20 to 30 kilometres and eventually have an impact on populated areas downstream."

That is because the debris flow could destroy hydropower plants or block the Lillooet River, causing floods to sweep down the valley.

Into the abyss

For everything the scientists have been able to see on their treks to the glacier, this trip revealed a new and worrying discovery that became clear as Williams-Jones and backcountry guide Eric Dumerac hiked carefully toward another opening.

An alarm began sounding, warning of gas, but the concentration of hydrogen sulfide was not enough to warrant turning around. When they got closer, Williams-Jones could not quite believe his eyes or contain his excitement.

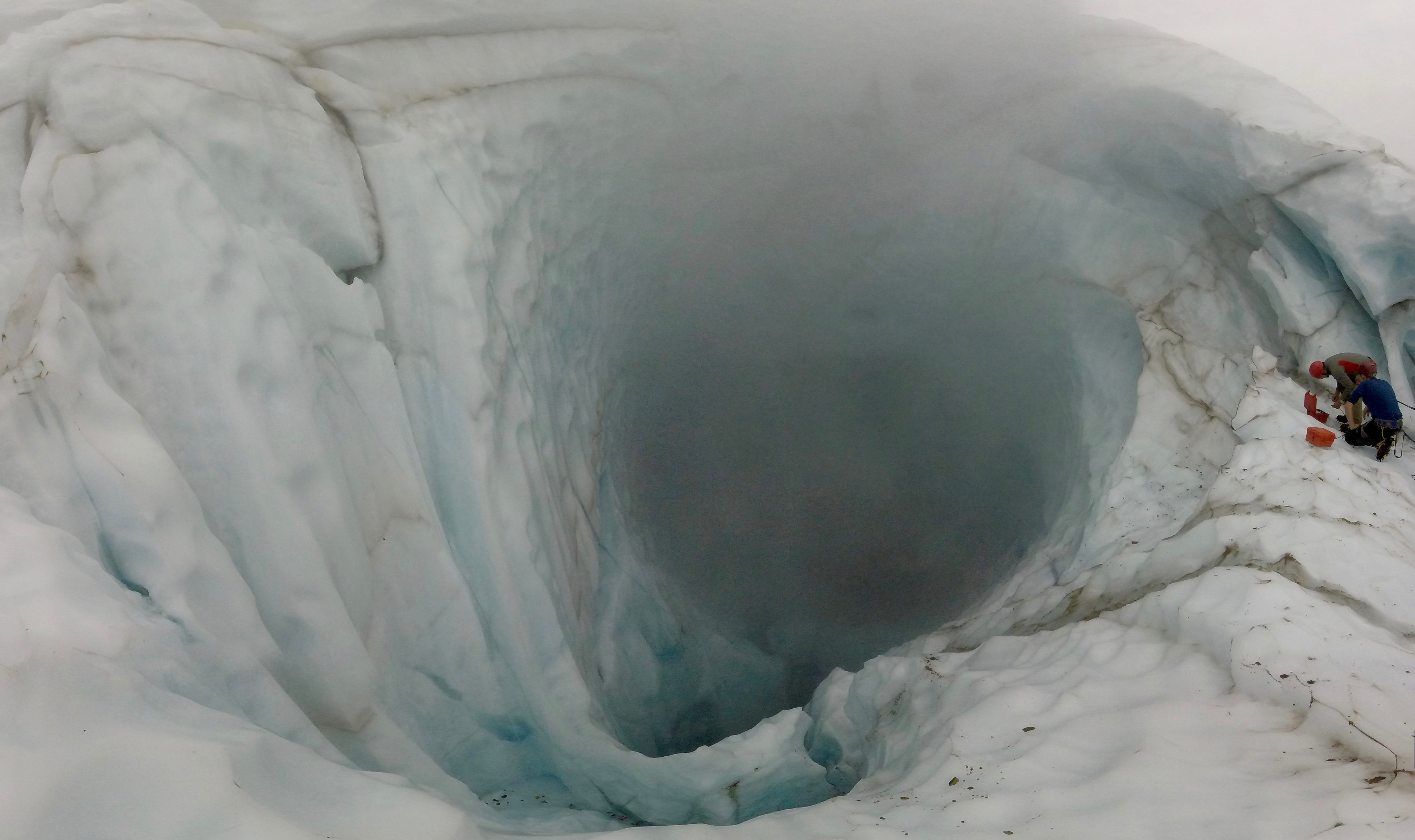

We are back where this story began — Williams-Jones, lying on his stomach, peering into the abyss; the ice cave near one of the fumaroles.

The ice had split apart, revealing what appeared to be the bottom of the glacier. Dumerac used an ancient tool, a rock, and some basic physics to determine its depth.

He threw it in and waited. After a few seconds, a loud thud filled the silence.

"About 30 to 40 metres. We maybe have 30 metres of ice beneath our feet," said Williams-Jones sounding serious and scientific.

Then, the childlike love of exploration took over.

"You don't get to see that everyday. That was amazing. It's as though someone took a laser and melted the middle of the glacier."

Clague, at SFU, laughed when he was told of Williams-Jones's reaction.

"He's a kid in a candy store," he said. "Scientists like Glyn are very passionate about what they do and, secondly, they love the outdoors, and they love chasing science."

Get a drone's eye view of the fumaroles atop Mt. Meager (Sky Pilot UAS)

None of that, though, takes away from the serious message Williams-Jones wants to deliver.

The ice cave discovery underscores the increasing instability of the volcano and, he says, the need for 24-hour, all-season monitoring and alarm systems to warn of landslides or even an eruption.

"I don't want to be seen as a fearmonger. I'm not saying the sky is falling, but I have to say, 'Look, this is important,'" he said.

"It isn't just an esoteric academic exercise. There is a true value in trying to understand what is happening here and what is changing so that people can prepare."

'Quiet but grumpy'

So far, though, the federal government has not provided the funding needed for the monitoring. There are other pressing concerns that grab headlines and dollars, such as forest fires and floods.

So Williams-Jones is encouraging private businesses operating in the area and people like Dumerac to help with any observations when they are near the mountain or to donate their time and services to help, as they did the day Williams-Jones and his crew flew to Mount Meager.

Williams-Jones calls them "citizen scientists" and is grateful for their help.

After six hours of work on the glacier, the sun started to slip behind the peak, signalling the need to end the day's research and fly back to base. Aside from the data on gas levels, other crews measured the depth of the glacier and the rate at which it is receding.

The information will all go back to the university where Williams-Jones and the others will continue their quest to understand what is happening at Mount Meager and what it suggests for the future.

Already, he knows the work they are doing could be used to help future research in volcanic regions with similar climates, such as Iceland, Alaska and even regions of South America.

"The science is so young," Williams-Jones said. "Volcanoes are enigmatic. Each one has its own personality."

Mount Meager's, he said, is "quiet but grumpy."

Even after all his years of work in the field, Williams-Jones says, every time he stands on a volcano, he is filled with wonder.

"What I find spectacular about volcanoes is that they ground you as a human being and make you realize how inconsequential you are."