December 28, 2020

John Doe No. 26 places two weathered hands on his dining room table, smoothing out creases in a holiday tablecloth as he talks about the monsters of a Christmas past.

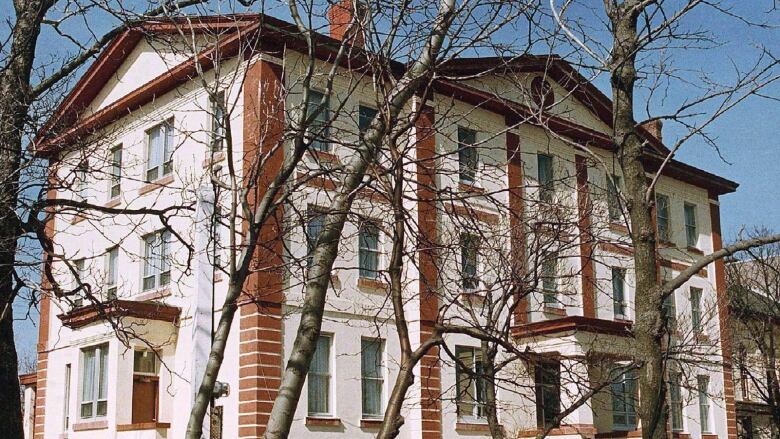

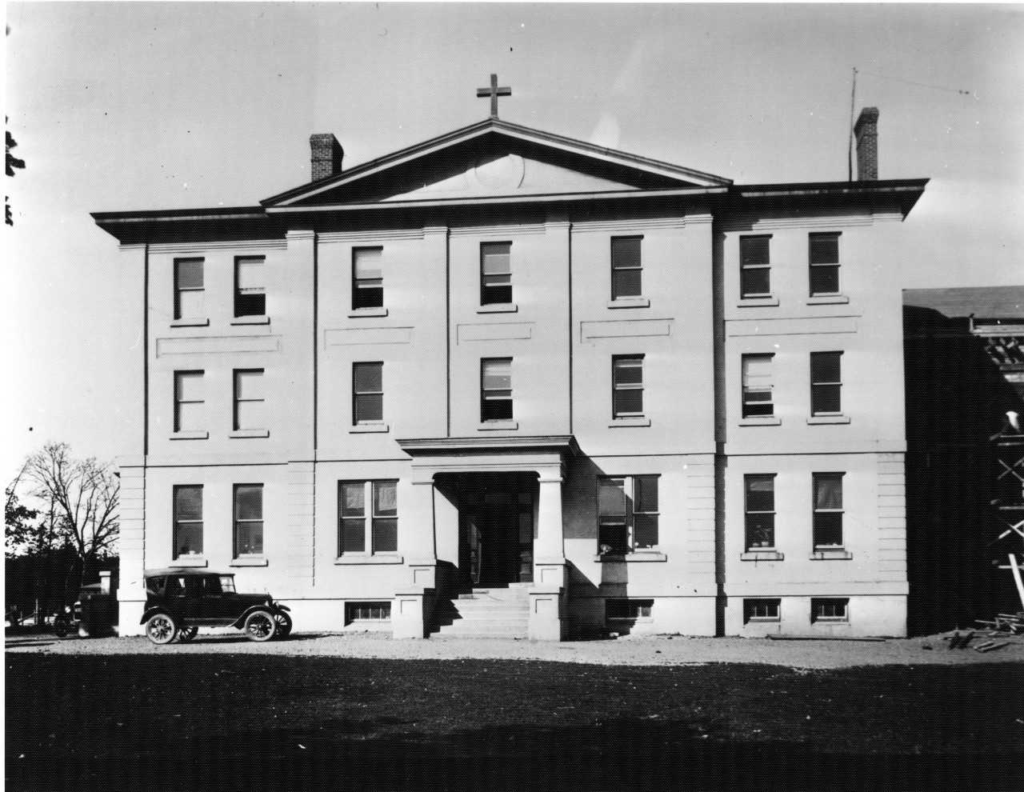

Dec. 25, 1955, was the day he put a stop to the abuse he suffered inside the hallowed walls of the Mount Cashel Orphanage in St. John’s.

For seven years, sadists in black robes and white collars desecrated so much that was innocent in the child. The abuse was physical, sexual and psychological.

“The punishment was not to correct the behaviour,” he said. “The punishment was satisfaction to the people who were applying the punishment. You were beaten with straps, with sticks, with fists, whatever. It made no difference and there’s no recourse to anyone.”

When he was big enough to fight back and angry enough to take no more, he used those rough hands to crack a chair over the skull of a man later sentenced as the worst of the worst — Brother Ronald Lasik.

Then just 15, John Doe No. 26 spent Christmas night with a shank crafted from a hayfork under his pillow to defend against any Christian Brother who came for retribution after the lights went out.

But nobody came. He was expelled the next day and left to fend for himself as an orphan in the dead of winter.

Now, he's hoping the Supreme Court of Canada will render a decision early in the new year, and affirm the Roman Catholic Church was responsible for what happened to him decades ago at the hands of a lay organization called the Christian Brothers of Ireland.

Him, and more than 100 other children.

There are publication bans protecting the identities of the victims — who are now elderly men — involved in the ongoing lawsuit. They are instead referred to by their John Doe numbers.

This legal battle over responsibility at Mount Cashel has been ongoing since the late 1990s.

The Archdiocese of St. John’s claims no ownership over the orphanage, and no affiliation with the brothers who worked there. A Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador judge sided with the church in 2018, but three appellate judges in the province sided with the victims in July 2020, ruling the Catholic Church was liable for damages because of its close relationship with the Christian Brothers.

Canada’s top court will soon decide whether to hear one last appeal or put the case to bed and leave the Catholic Church to pay for the sins of the brothers who ran the orphanage and school.

The case involves four plaintiffs — one of whom is dead, while the other three are in their 80s — who were residents at the orphanage in the 1950s.

Mount Cashel came to national prominence with a judicial inquiry that concluded in 1990 about abuse at the orphanage in the mid-1970s, and a deal the government made to effectively expel two sexually abusing brothers in return for no criminal charges. The inquiry was triggered at the same time as a new criminal investigation, which resulted in a series of criminal trials.

Those cases also opened up older instances of sexual and physical abuse at Mount Cashel, dating back decades. The case heading to the Supreme Court of Canada includes those older cases.

The consequences of a win for those four men would go far beyond themselves. There are dozens of others who could file lawsuits in Newfoundland and Labrador against the Archdiocese of St. John’s to pay the bills that the Christian Brothers left outstanding when the organization went bankrupt in 2012.

It’s a decision that could shape the future of the church in a city that was once a Catholic stronghold.

It's being watched by the church from St. John's to the Vatican, and by lawyers around the globe looking to prove the Roman Catholic hierarchy is liable in similar situations.

The boys

John Doe No. 26 came from a large family on Bell Island where God was at the centre of everything.

His father returned from the Second World War overseas on a compassionate discharge to care for his ailing wife.

When she died in 1947, he couldn't shake her loss. Before long, he couldn't shake his addiction, either.

“A change came over my father. He lost everything. His whole world was my mother,” John Doe No. 26 said. “And he began to drink.”

After about a year, all five sons were taken from the home. The four older boys — ages five, eight, nine and 10 — were placed in Mount Cashel. The youngest son joined them a year later.

“From the time we got in there, until the time we got out, there was an atmosphere of fear and foreboding,” he said. “Everything was a physical beating for any infraction or perceived infraction.”

Sometimes it was a punch in the head. Other times, the brothers would lift a child up by the belt, stretching their pants tight across their buttocks and whip them with a swatch of leather.

The abuse was constant and unforgiving.

It was endured by countless other children, including one who now goes by John Doe No. 50 in court documents.

Seven hours skating up and down a frozen pond on a crisp winter’s day is the last happy memory John Doe No. 50 has before his childhood was fractured.

His adolescence was split in two acts — before the orphanage and after the orphanage.

Now 80, Mount Cashel lingers in his mind and looms over his life as a chasm where innocence plunged into nightmares.

He was a 12-year-old boy then, skating away from the fresh grief of his mother’s death. His uncle pulled up alongside the ice and ended the world as he knew it with one sentence.

“We’re taking you to the orphanage.”

He and his two younger brothers were uprooted from their rural life in St. Lawrence, N.L., and taken about 300 kilometres by boat to St. John’s. With their mother gone and their father dealing with the amputation of both his legs, the boys became wards of the Christian Brothers at Mount Cashel.

“I think my father just thought he was doing what was best for us,” John Doe No. 50 says today, almost 70 years later, from his home in St. John’s.

His father, like many poor and suffering parents who sent their sons to the orphanage, could never have known what was happening.

And when he was told, John Doe No. 50 said his father refused to believe it.

The abuse

The beatings started almost immediately.

His voice shakes today as he recalls the constant threats and the psychological torture he faced on a regular basis.

There was one instance where a brother beat him with a stick after a sports practice. The brother cut him across the knee so badly the child had to go to hospital for stitches.

“He said ‘Remember, don’t tell the truth.’ So I said ‘OK.’ I wasn’t OK, but I knew what he had in mind,” he said, choking back tears. “That was something I’ll always remember.”

Shower time was a particularly anxious occasion in the orphanage. Hot water was in short supply with so many boys living in one place. As John Doe No. 50 tried to quickly splash water over himself and get out, Brother Ronald Lasik watched.

Lasik towered over children like a giant, the largest of the brothers at the time. His victims said he possessed a maniacal temper and an unpredictable malice.

He ordered the boy back into the shower and told him to lather up. He was naked, cold and had no escape from the inevitable abuse to follow.

Tears well in his eyes and his voice falters as he remembers the story today.

“He took a strap and laced me. I’m thinking, hey, there’s nothing you can do. You can’t defend yourself. The first thing they’d do is kick you out. And you had enough common sense to know, where are you going to go? If they kick you out, you’re finished. And I had two younger brothers that I was looking after pretty good.”

Even with the rampant physical torture throughout the school, most kids didn't know the full picture of what was going on at night.

WATCH | Lawyer Geoff Budden spoke with the CBC's Anthony Germain about a Catholic diocese's decision to appeal a Mount Cashel verdict:

John Doe No. 26 found out in Grade 7. He was repeatedly sexually assaulted by Brother J.E. Murphy, a man who would later serve 20 months house arrest for the crimes he committed at Mount Cashel.

As time went on, two other men began sexually abusing him as well — including Frank Clancy, an electrician who did work at the orphanage.

The children didn't know anyone other than their own self was being abused. They felt isolated. And yet it was so pervasive among the adults in the institution that John Doe No. 26 discovered even the electrician knew it was a haven for child abusers.

Years dragged by and John Doe No. 26 got bigger. He earned a reputation as a tough guy, but it was only a defence mechanism. On the inside, he was sensitive and lonely.

Some brothers had a habit of pitting boys against each other. John Doe No. 26 would later testify that Brother Murphy took it too far one night. He said Murphy ordered a pair of children to snatch up a stray dog he took care of and to throw it out the top floor window.

They did as they were told.

That was the last time Murphy would do anything to hurt John Doe No. 26 — physically, sexually or otherwise.

"I was so enraged. I told him what he was and this sort of thing," he said. "He didn't come after me. He did not come after me. And after that, everything stopped. He knew I had reached the point."

One other incident led to John Doe No. 26 reaching his breaking point.

It was Christmas Day, 1955, and a local organization sent a container of candy to the orphans at Mount Cashel.

Brother Lasik had John Doe No. 26 dole out the candy as younger kids lined up in front of him. He was excited to do a good deed at Christmas, but Lasik had other plans.

He pointed out a boy nearing the front of the line, and ordered John Doe No. 26 not to give the child any candy.

Lasik made him do it again, excluding another little boy in the line.

And again.

And again.

John Doe No. 26’s heart broke over and over as he told each little boy they couldn't have candy at Christmas.

"I was going through f--king agony," he says today.

After seven years of constant beatings, molestation and fear, he was broken.

Later that night, the boys went upstairs to watch a movie. Off to the side of the auditorium, John Doe No. 26 saw Lasik laying a beating on a close friend of his.

"I lost everything. I guess it must have been pushed on, encouraged by what went on downstairs. So I picked up a chair, I went over and I crowned him with it."

He pushed Lasik off his friend and called him a coward.

Lasik did nothing.

The two boys slept next to each other that night with a makeshift spear under a pillow, fully expecting Lasik or someone else to come for them in the middle of the night.

"They didn't come."

The next day, they were expelled from the orphanage.

Seven years of daily hell were finally over.

The reckoning

The orphanage was quiet from the outside.

It was known for its brass band and athletics. Its Christmas raffle was an annual hit, where people could win prizes like live chickens and feel good about giving money to children in need.

And then, in 1989, the benevolence of it all was blown to pieces.

John Doe No. 26 saw the news on TV — a public inquiry was being opened in relation to a coverup at Mount Cashel.

He'd done his best to live a normal life until that point. He had a university degree and a respected profession, and was a decorated coach.

His wife found him in the basement when she came home that day.

"I completely went to pieces," he said. "I was uncontrollable. Finally I settled down enough to tell her what happened to me."

He sat down that night and wrote a deposition for the Hughes Inquiry, before anyone could even ask him to be involved.

As the words flowed out onto the page, the flood of emotions was overwhelming. There was horror, but also comfort in knowing he wasn't an isolated case.

People began coming forward with allegations not just of abuse at Mount Cashel, but of an elaborate coverup involving police and social workers.

The Hughes Inquiry blew the lid off the entire scandal and proved that a Royal Newfoundland Constabulary officer had interviewed 24 boys in 1975 about physical and sexual abuse at the orphanage. He'd even secured confessions of molestation from two Christian Brothers.

And then he was ordered by his superiors to destroy his report and write a second one, scrubbing from it all references to sexual abuse.

Out of the inquiry came criminal cases against several Christian Brothers, and the electrician Frank Clancy.

John Doe No. 50, who had also gone on to live a productive life with a loving family, did his part to help put Brother Lasik behind bars.

Lasik received the stiffest punishment of anyone — 11 years, of which he only served four and was deported back to the United States.

He died in February 2020. No obituary was posted online. He remained a registered sex offender in the State of New York until his death.

Civil court filings in Illinois allege Lasik also assaulted two boys at a high school in Chicago after his time at Mount Cashel.

The law

As the dust settled on the Hughes Inquiry and the criminal trials, the fight for compensation began.

Civil lawsuits helped solidify household names out of lawyers like former Newfoundland and Labrador premier Danny Williams, and longtime Member of Parliament Jack Harris.

But a case taken by a lesser-known litigator in St. John's would prove more challenging.

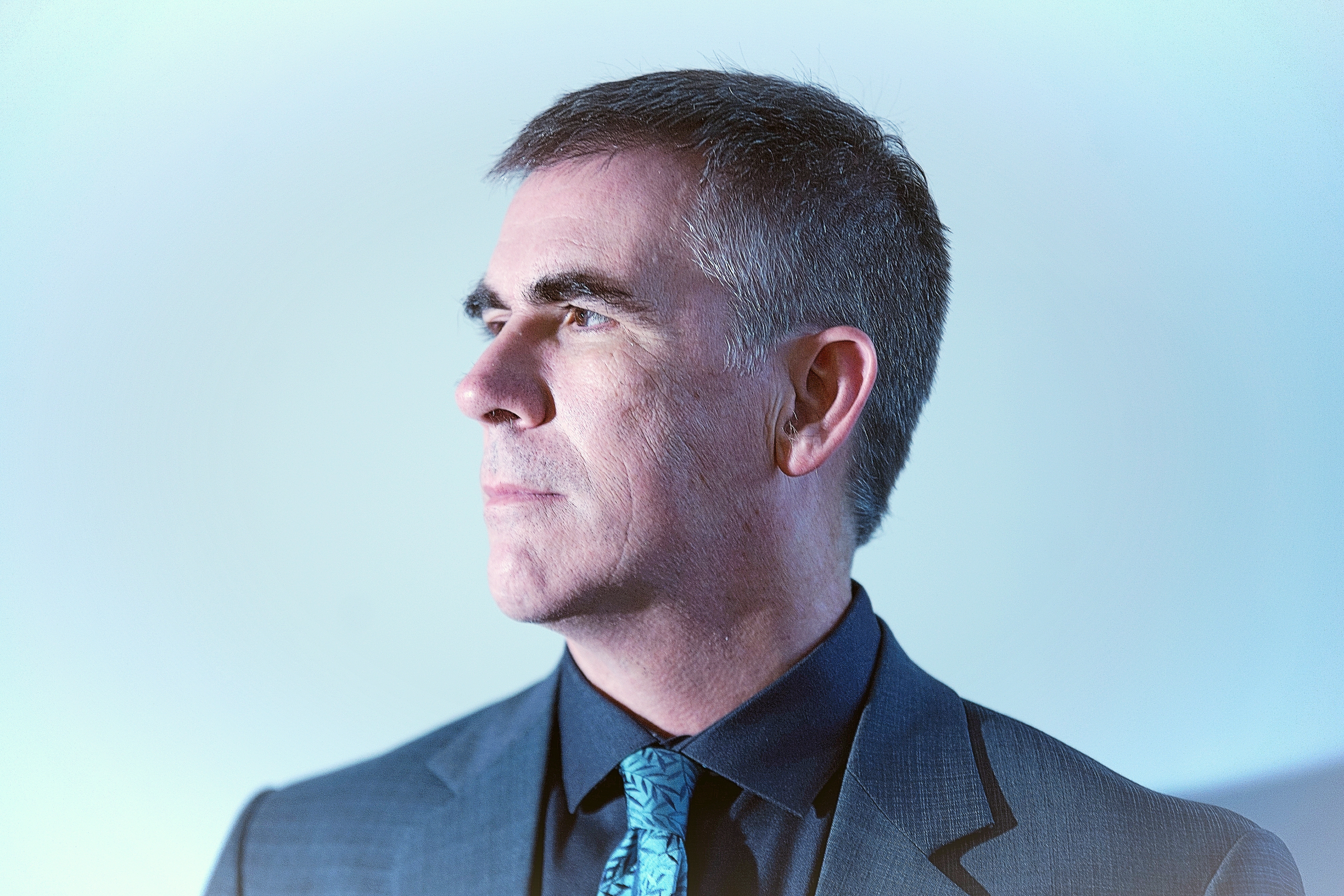

Geoff Budden never intended to take the case.

In 1997, he was approached by someone on behalf of a Mount Cashel victim from the 1950s who wanted to sue the brothers and the church. Knowing it was a tall order, Budden passed.

A while later, the person called back again and said nobody else would take the case.

“So I did some research and thought that I did see a viable path forward and then I was retained by these guys," Budden said.

It started with one man, and eventually grew to 60 victims from the same era, including John Doe No. 26 and John Doe No. 50.

The case immediately became bogged down in complications. Mount Cashel was staffed with teachers from the Congregation of Christian Brothers of Ireland, but they were not incorporated in Canada at the time.

It was clear there was an American connection — most of the early brothers came from the United States — so Budden formed a partnership with an American lawyer and went after the Christian Brothers Institute in New York.

Years of back and forth ensued, with the institute claiming it had no jurisdiction over the brothers at Mount Cashel and therefore shouldn't be sued for their wrongdoings.

Then Budden's team found a document filed at a New Jersey courthouse where the Christian Brothers Institute was suing its insurance company for failing to cover child abuse claims it settled in that state. The document stated the opposite of what the institute had claimed in Newfoundland and Labrador, and clearly stated it was responsible for staffing at facilities outside New York.

The Christian Brothers Institute folded its hand, and the lawsuit proceeded.

But there was always a bigger target than the brothers.

The church

For 22 years, Budden and his group of lawyers and John Does have been trying to prove the Archdiocese of St. John's should pay for what happened at Mount Cashel.

Budden's team had two arguments. One, that the church knew about the abuse and did nothing, and two, that the church was in a position of liability through its close relationship with the Christian Brothers.

What the lawyers turned up on the first argument shook John Doe No. 26 to his core.

Budden's team presented evidence that at least seven children went to confession and told the chaplain at Mount Cashel about the physical and sexual abuse they were enduring.

They spoke up when John Doe No. 26 couldn't.

“These kids stood up and I laud them continually and I always will for the stand they took, the courage they showed," he said.

Despite the compelling evidence of confessions, Justice Alphonsus Faour of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador rejected this argument for several reasons.

There was insufficient evidence about what the chaplain did or didn't do with the information, and the judge also said it was unclear whether or not he understood what the boys were telling him.

"The testimony and statements provided indicate only seven disclosures out of potentially hundreds of confessions heard by the priest during the relevant period," Faour wrote. "Those disclosures may have either not been believed or may have been misunderstood by the confessor.”

John Doe No. 26 had been in and out of touch with his religious beliefs throughout his life. That line in the decision was the final blow.

“I was completely slayed. I could not find any reasonable explanation for that decision by the judge. I mean, if I’ve got to shoot seven people to show evidence that I have committed a murder — one is too many. But only seven? I lost all faith.”

Faour ruled against Budden's team on both arguments and sided with the church in his 2018 decision.

The surviving members of the original lawsuit were disappointed by the decision, but had not given up. They urged Budden to appeal it to the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador.

On July 29, 2020, three judges with the appellate court sided with Budden's team on the issue of vicarious liability, and ordered the church to pay the outstanding damages to the victims or their estates.

“It’s beautiful. It’s powerful. It’s satisfying and it makes me stand a little taller," John Doe No. 26 said. "Somebody has come out and said the church is responsible.... Somebody else stood up for us.”

In September, the church decided to exhaust its final appeal. It asked the Supreme Court of Canada to hear the case.

The country's highest court hears about 13 per cent of the applications it receives each year.

A decision on whether or not it will hear the case is expected by early January.

The consequences

This decision could be the last of the major rulings on Mount Cashel. There will be nothing left to dispute about what happened and who is responsible.

If the court turns down the appeal, it could set off a new flood of litigation against the church. Budden estimates about 160 former Mount Cashel residents have been involved in lawsuits against the Christian Brothers. Most were never paid in full.

This decision would put the cheque in the church's hand.

South of the border, one lawyer is eagerly awaiting the outcome.

When it comes to suing the church, Mitchell Garabedian is regarded as a pioneer.

The Boston lawyer, famously played by Stanley Tucci in the Academy Award-winning best picture Spotlight, helped lift the lid off clergy abuse in the United States in the 1990s.

He's represented 2,500 clients in clergy abuse cases around the world.

Garabedian believes the highest levels of the Catholic church are watching just as intently as he is, and for the same reasons.

Vicarious liability is a relatively new area of law, and this case could set a road map for clergy abuse cases around the world.

“Every time you add a layer of an institution, it gets more difficult to prove that institution’s involvement in the case," Garabedian said. "So the Vatican is concerned this case will be a very strong example of multi-layered institutions within the Catholic Church being successfully sued.”

The Archbishop of St. John's declined an interview for this story, saying it would be inappropriate to speak before the case is finished.

Budden said the appeal court decision, if upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada, is significant not just for the church, but for any person or institution that works in child protection.

"Out of that comes laws that I think will make this a better country," he said. "I think anybody now who is involved in caring for children knows they not only have a moral duty to act a certain way, they have legal duties. And if they fail in those duties, guess what? They're facing some pretty heavy consequences."

John Doe No. 50 hopes he can soon walk away with a satisfactory ending after so many years of fighting.

For him, it's not the money. It's the acknowledgement of responsibility and hopefully an apology.

"I think we're entitled to it," he said with a tear in his eye.

"There's a lot of our guys who have died. They never got to see anything happen. And to me, that's cruel. I only pray that I stay around long enough, not just for compensation, but to have this wiped from my mind, so I don't have to think about this anymore."

John Doe No. 26 doesn't expect an apology, and wouldn't believe it sincere after all the time and money the archdiocese exhausted fighting against them.

He's watched as the boys of Mount Cashel helped shape St. John's over the decades, for better and worse, sometimes wondering if they, too, suffered the same abuse as him.

Some became politicians, tradesmen, teachers.

Plenty of others became lost along the way, falling into drugs and alcohol and repeating the cycle of abuse.

“The highway of life is strewn with the wrecked bodies and minds of Mount Cashel orphans," he said.

"I tell you. I know so many. I know so, so many. My god.”