January 10, 2020

Marcie Stevens has a plan that's straightforward and strikingly poetic.

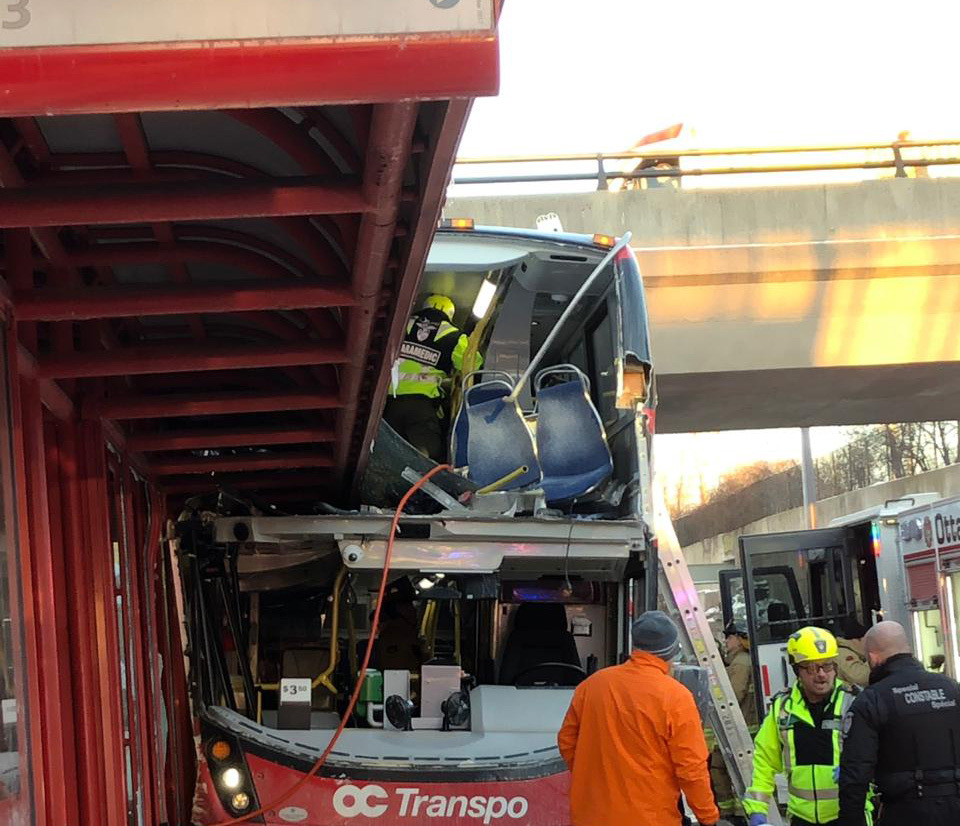

In the coming months, Stevens plans to stride confidently aboard an OC Transpo bus — more than a year after losing both her legs when the double-decker she was on collided with the overhang at Westboro station.

Stevens was one of at least 23 people injured in the Jan. 11, 2019 collision, which also killed passengers Judy Booth, Bruce Thomlinson and Anja van Beek. She'd been sitting in the upper level: her preferred spot, but also the portion of the bus that took the brunt of the impact.

"It all happened pretty quickly. One minute I was putting my phone away. The next minute the seats were coming toward me," Stevens recalled Thursday, two days before the one-year anniversary of the crash.

"I was kind of thinking, oh, this is not good. That's all I remember. And then everything coming towards us, the screaming, the crashing of the windows, the panic."

Stevens is among the many passengers who've now filed lawsuits seeking compensation for their pain and suffering. She's seeking $19 million from the City of Ottawa, OC Transpo and bus driver Aissatou Diallo, 42, who is also facing 38 criminal charges.

Despite being pinned in her seat, Stevens recalled being calm enough to call her husband, informing him she'd been in a crash and that he'd have to pick up their kids as she'd be late getting home.

She then called her work to say she wouldn't be in on Monday.

"I don't know if I can say I was in shock. I think [it] was just, this is the way I am. And I think I stay pretty 'cool cucumber' when it comes to incidents and accidents," Stevens said.

At the time, Stevens couldn't see her legs. She initially thought her injuries weren't that bad, a belief she maintained from the rescue — she said firefighters had to use the jaws of life to get her out — up until her arrival at hospital, where she was sent for a CT scan.

"Then my blood pressure [started] dropping," she said. "That's when I knew it was serious."

Bus crash survivor facing one-year anniversary with 'mixed emotions'

Stevens soon learned that doctors wouldn't be able to save her legs. Both had to be amputated above the knee.

"When you get news like that, you kind of break down for a bit," she said. "[Then] you kind of think to yourself, 'Well, this is the cards that have been dealt to me, so let's try to make the best of it, pull up the big-girl panties and keep truckin'."

Making the best of it, Stevens said, would necessitate learning to walk again — and that would require prosthetic limbs.

Her doctors told her she'd first need to lose nearly 20 kilograms to limit blistering and tissue degradation. After working out three times a week at the gym and swimming twice a week, she's managed to lose nearly 30 kilograms.

She's recently been given a prescription for what she calls her "training wheels": shortened prosthetic legs designed to let her gradually work up to full-fledged models.

For Chris Stevens, his wife's willpower comes as no shock.

"She's bloody well indestructible," he said. "Nothing surprises me. When she says, 'I'm going to get up, I'm going to walk, I'm going to walk onto a bus, watch me do it," my [reaction is], 'Oh yeah, of course.'"

Stevens's prosthetic limbs won't be cheap, however; nor will the other adaptations she and her family have had to make since the crash. For instance, they've realized their current home is now too cramped, so they're moving to a custom-designed home that's much more accessible.

Those challenges help explain the $19-million lawsuit.

"This is what we've estimated [it's] going to cost us through a lifetime," said Stevens, adding she can't go into depth about the suit as it's still before the courts.

Stevens said the past year has taught her she's "a lot stronger" that she'd ever realized, and that with both determination and the support of her family, she can "do anything." And while there are still uncertainties, Stevens is keeping her eyes focused on her immediate goal: taking that first step back onto the bus.

"There's still the lingering fear [that] I'm not going to be able to walk, it's going to be too painful, the prosthetics won't fit well," she said.

"But I'm going to give it my all and I'm going to try my darndest to be back to what I was before — or at least somewhat back to where I was."