June 13, 2021

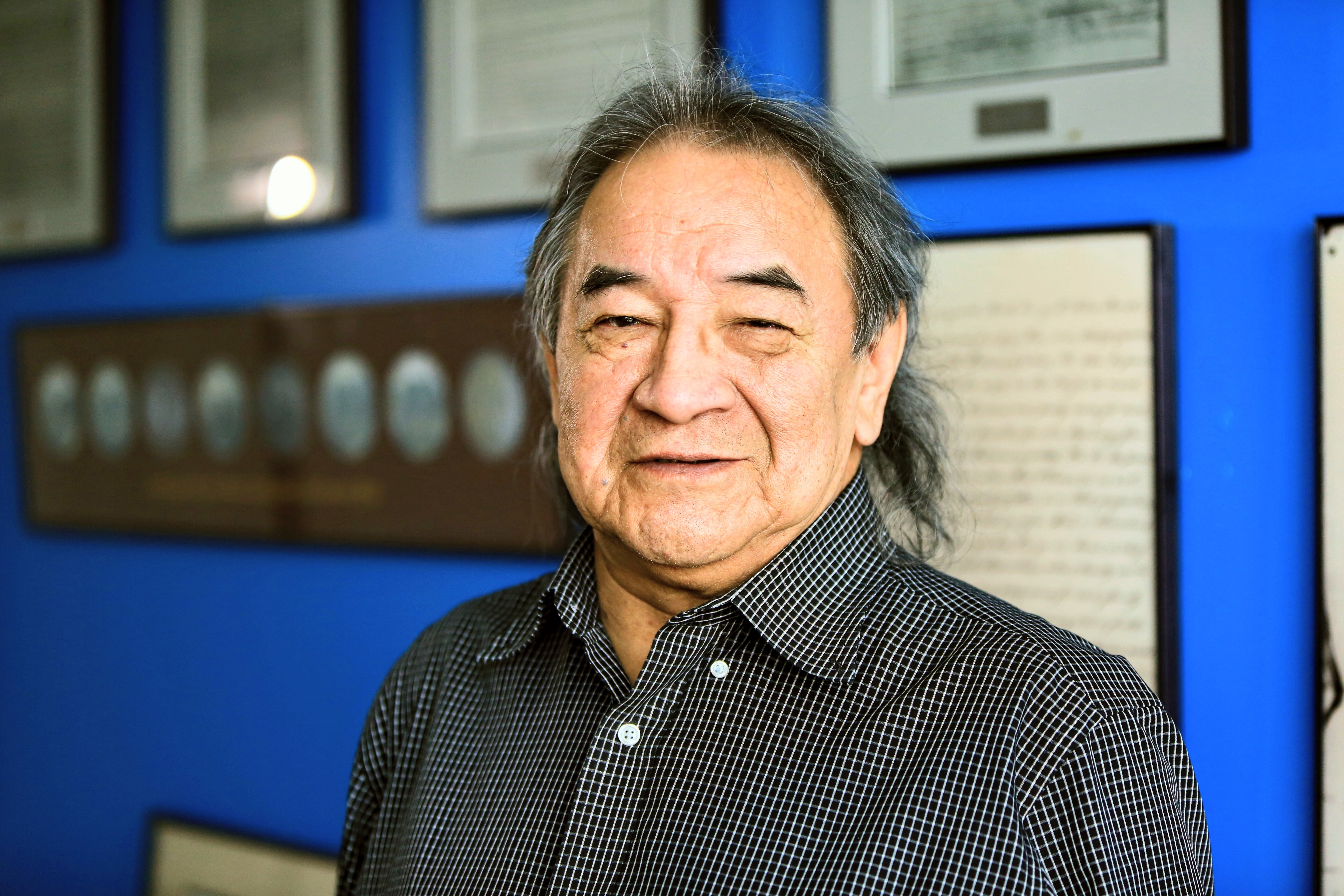

Stewart Lloyd Hill says he has a vision and it's an ambitious one.

Hill, who has a doctorate in natural resources and environmental management, wants to ensure that when he's done his time on earth, all northern Manitoba communities have equitable access to clean drinking water.

"I have no illusions that it's going to be easy," Hill says. "It's probably going to cost billions of dollars. It'll probably take a lot of time. But I'm not discouraged."

Hill's got the lived experience to fuel his vision. He grew up in God's Lake First Nation. Treaty 5 territory. A bracingly beautiful piece of terrain about 550 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg accessible by plane, boat or winter roads, located on the shores of Manitoba's seventh largest lake, Gods Lake.

Water, water everywhere and yet …

"All my life, all my life on reserve, we hauled water," he says. "My parents never knew running water."

Today, little has changed.

At any time, up to 74 per cent of God's Lake residents do not have safe drinking water, Hill says. It's a statistic that informed his research while completing his doctoral thesis in environmental studies last year.

"I always came up to that question, 'Why? Why is it like this?'" he says.

Ethically, it doesn't add up — there's a grossly imbalanced have versus have not access to Canada's clean water supply, he says.

"I think of mainstream Canada and a country as rich as Canada," Hill says, "there shouldn't be the use of cisterns, there shouldn't be water issues on reserves."

What's more, he argues, legally it doesn't add up. It's a breach of contract.

"It speaks to discrimination and racism, to be blunt."

Specifically, it's a breach of Treaty 5 — a historic agreement made between First Nations communities and the Crown in 1875. (In 1909, God's Lake community members entered into an adhesion to the treaty, effectively joining it.)

Treaty 5 is one of seven numbered treaties between Manitoba First Nations communities and the Crown dating back to August 1871.

What is a treaty? Here's what treaty agreements really mean, and why they're relevant to all of us.

The First Nations communities entered into these agreements in good faith and with a bottom line mandate: to allow the Crown to successfully, respectfully use their land.

That was the deal. That wasn't the reality.

Hill says he knows why.

"It speaks to discrimination and racism, to be blunt," he says.

History distorted

Loretta Ross has made a career out of correcting Canada's history lessons.

As the treaty commissioner with the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba, she's trying to undo the long-standing myths surrounding Canada's relationship with First Nations communities, specifically when it comes to treaties.

"There's such a negative image of First Nations people, and we have to go beyond that," Ross says. "It really is about understanding that relationship, understanding that history, because ultimately it is a shared history."

Ross still remembers the day her elementary school teacher announced to the class that they would learn about treaties.

"The teacher said, 'The Indians gave up all of their land and they were put on reserves,'" Ross recalls. "As a First Nation person, I was bewildered. Giving up your land. Who would do that?"

Her confusion soon morphed into despair.

"It left me with a feeling of being ashamed then of who I was and certainly of my ancestors and the leaders," she says.

"I had a feeling then that we weren't as smart. We couldn't have been as smart to be able to negotiate this."

The thing is, they didn't, she says.

"Our elders have always said there's more to the treaty-making process than the written text."

Historically, First Nations had long relied on treaty-making as a means to peacefully negotiate land use with other First Nations. It was a tried, true and honoured tradition.

"They always had treaty-making as a way of sharing the land, sharing the resources," Ross says.

Fast forward to 1871. John. A. MacDonald, Canada's prime minister, wanted to expand access to the land that First Nations communities had long called home.

MacDonald had a lot riding on the coveted stretch of terra firma. He had a railway to finish building that would connect the Prairies to the West Coast.

The Crown also had a pushy neighbour to the south — the U.S. — that was flexing its expansionist muscles with an eye to the north.

First Nations leaders, meanwhile, knew they needed change in order to survive; buffalo hunting was on the decline and European illnesses, introduced by the newcomers, were threatening their people, putting future generations at risk.

So they agreed to share the land with the Crown newcomers, in exchange for equal access to health, education and livelihood resources, with the understanding that their traditional way of life would be protected.

Thus, treaties were forged — legally binding agreements between First Nations, the Crown and the Creator.

They were supposed to be mutually beneficial. In the years that followed, that's not how they were interpreted.

"Our elders have always said there's more to the treaty-making process than the written text," Ross says.

In honour of Mother Earth

Elder Dennis White Bird wants to get one thing very clear.

"We did not sell the land. We were not pawns of war and we did not give up the land," the former treaty commissioner of Manitoba says.

"We agreed to share the land."

White Bird says the misinterpretation of treaties began almost immediately.

They were sacred agreements, witnessed by the Creator and sealed during a pipe ceremony, he says. But the written words themselves — the ink to paper that spelled out the terms — were in English.

"The language issue, the interpretation, seemed to work against the First Nation people," White Bird says. "When the agreement was crafted or was written in Ottawa or wherever it was, it came out that we ceded the territory."

Elders of the day had a different interpretation, he says. They never agreed to surrender the land, nor would they conceive of such a thing.

"For us to turn around and give up our Mother is like giving up our life," he says.

"All our dependencies come from Mother Earth. If we need clothing, it comes from Mother Earth. If we need food, it comes from Mother Earth. If we need medicine, it comes from Mother Earth. So for us to turn around and give up all our rights to the Crown is erroneous."

If the language barrier contributed to the misinterpretation of the treaties, the Indian Act solidified it.

The federally drafted act was introduced in 1876, just five years after the creation of Treaty 1. It became the Crown's guiding rule book in managing the lives of First Nations people.

And the underlying mandate of the rule book? To undermine the Indigenous presence in Canada — in everything from their language to their livelihood, White Bird says.

From that point on, every treaty agreement was interpreted through the lens of the act.

Suddenly, equal access to education meant removing children from their communities and forcing them to attend the now notorious residential schools.

Equal access to hunting and fishing meant succumbing to Crown or provincial rule when it came to quotas, locations and access.

"Our whole life has been under seige."

At times, the Crown even policed Indigenous freedom of movement, telling them where they could and could not go, and what they could or could not do.

"You cannot leave your reserve unless you have my permission. You cannot have ceremony, a large gathering of people, unless you have my permission," White Bird says.

And forget about fighting the restrictions in court. For decades, even that right was taken away.

"The government of Canada passed a law that we could not hire lawyers and … it was against the law for a lawyer to represent a First Nation community — a double whammy," White Bird says.

"Our whole life has been under siege."

Breach of agreements

Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Grand Chief Garrison Settee wants people to know about Treaty 6 and what's known as the medicine chest clause.

The clause guaranteed equitable access to available health-care tools of the day.

At the time it was drafted in 1876, its meaning was literal: an actual medicine chest had to be provided by the Indian agents (federal government representatives who enforced the Indian Act), to serve whatever health-care needs existed.

Today, it's supposed to mean the 21st century equivalent, says the grand chief of MKO, an advocacy organization for Manitoba First Nations signatories to treaties four, five, six and 10.

"In our world, when you have a medicine chest, that means in the chest to have that complete health-care system — complete. Everything that you need," Settee says.

That treaty clause was not honoured, he says.

Think Jordan River Anderson. In 2005, the death of the five-year-old from Norway House Cree Nation, in Treaty 5 territory, ended a two-year disagreement over who would pay for the home care costs associated with his complex genetic disorder.

As a result, Jordan's Principle was adopted by the House of Commons in 2007.

Its directive was clear: the needs of a First Nations child requiring a government service should always take precedence over jurisdictional issues, when it comes to deciding which level of government pays for it.

In other words, provide the medical care first; fight over the bill later.

To this day, however, jurisdictional challenges continue.

Think Brian Sinclair. His 2008 death after waiting 34 hours for care in a Winnipeg hospital emergency room was later attributed, in part, to systemic racism against Indigenous people.

But one need look no further than at the COVID-19 pandemic to see the medicine chest clause continues to be challenged, Settee says.

In December 2020, the federal government proposed a plan to reserve some COVID-19 vaccine doses for First Nations communities. Manitoba's premier then expressed concerns that there would not be enough left for the rest of the population.

"This puts Manitobans at the back of the line. This hurts Manitobans, to put it mildly," Premier Brian Pallister said at the time.

Settee's response is blunt.

"It's just a continual perpetuation of the condescending arrogance," Settee says. "That undermines who we are as a people and consider[s] us to be not to the same level to the rest of society."

The land we share: Find out what we're really saying whenever we acknowledge the land we live on.

There are other present-day breaches of the treaties, say Indigenous and Métis leaders.

Think hunting: In 2020, Manitoba proposed a continued moratorium on moose hunting on treaty territories, citing conservation concerns.

That perspective was challenged.

“We have a right [to hunt],” Manitoba Metis Federation president David Chartrand said at the time. “We have a right, not a privilege.”

"If those treaties were honoured in the [proper] spirit and intent, we would not be petitioning the government for housing ... for better health systems ... for better schools."

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Arlen Dumas concurred.

"We're seeing an infringement of jurisdiction," Dumas said.

Think land claims: In March 2021, the province proposed Bill 51, which would put a time limit on any Indigenous land claim challenge based on treaty rights.

Think access to clean water: As of 2021, some northern Manitoba communities have limited access to clean drinking water, despite federal promises over the years to invest in the infrastructure needed to build, maintain or update existing water systems. (In 2018, the feds committed to spending $1.8 billion to make it happen. Critics say they're still waiting).

"If those treaties were honoured in the [proper] spirit and intent, we would not be petitioning the government for housing, we would not be petitioning for better health systems, we would not be petitioning for better schools," Settee says.

Righting the wrongs

Three decades after Loretta Ross's grim classroom lesson on treaties, her teenage daughter found herself in another classroom, with another teacher, facing the same history lesson.

The takeaway, however, was very different, Ross says.

"He said, 'The original people here were Anishinaabe and Innu and Cree and Dakota, and it's through the treaty-making process that we're here, so it's their land,'" Ross says. "The teacher said, 'They agreed to share the land through the treaties and therefore allowed us to settle and to prosper.'"

The teacher's words meant the world to both Ross and her daughter.

"She felt proud, as opposed to the way that I had," Ross says.

There are other signs that past wrongs are beginning to be righted.

In 2019, seven Treaty 1 First Nations — which make up the Treaty 1 Development Corp. — got the green light to develop the former Kapyong Barracks, a military base that lay vacant for decades, in the heart of Treaty 1 territory. The pending development could morph into an economic win for both treaty First Nations and others.

In December 2020, leaders of Peguis First Nation took ownership of efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 in their community, imposing and lifting restrictions on their own terms, as opposed to allowing the province to mandate restrictions for them.

It gives Loretta Ross a sense of optimism.

"You know, they're working to make their communities healthy," she says.

"It just doesn't take much to work together to recognize and say, 'I respect that. I respect your territory. I respect your leadership. You know, how can we work together?'"

It gives Elder Dennis White Bird a sense of commitment.

"The truth will set us free, and it's not only true for us as First Nations people, but it's also true for the government of Canada, the government of Manitoba, and it's true for the country," White Bird says. "If we're truthful, that we will have freedom in our relationship."

It gives Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Grand Chief Garrison Settee a sense of purpose.

"We need truth and reconciliation. You cannot have reconciliation without the truth and Canada must hear the truth," Settee says.

It gives Hill a sense of hope.

"I say that we're in evolution," he says.

"We want to move forward in this relationship. I know there were genocidal policies, but as we move forward, I think it should be in the spirit of hope."

Indigenous leaders share the real story behind treaty agreements, and how history got it wrong.