June 1, 2018

It all started when Charles Anastasia’s boat sank.

This was in 1979, when 26-year-old Anastasia took to the ocean every morning to fill his nets with cod, back when that fish was still the beating heart of the Atlantic fishery.

With his boat pinned 100 kilometres offshore during a “perfect storm,” a floating telephone pole skewered the hull like a marshmallow on a stick. The eight-man crew barely got a mayday out and survival suits on before the vessel sank beneath the 20-metre waves.

Two fishermen couldn’t swim, so the group inflated balloons for buoyancy and tied themselves together. They were rescued minutes before the search was called off.

When that boat went down, so did Anastasia’s prospects. Soon after, the broad-shouldered, wide-cheeked man uprooted his life and moved to Alaska, buying and selling seafood for a living.

It was here he encountered snow crab: a flat-bodied, 10-legged crustacean that transformed his life and would soon, on the other side of the continent, revolutionize an industry.

Like lobster, millions of dollars worth of New Brunswick snow crab is sold internationally. Unlike lobster, it is almost impossible to buy snow crab in the province, even when a boat filled to the brim is moored in a nearby harbour.

The decades-old fishery was built by entrepreneurs like Anastasia, who have always targeted lucrative international markets with this premium delicacy. Until recently, snow crab wasn’t really on the radar outside the coastal communities where it provides employment and income.

But then snow crab fishing gear in the waters off northeastern New Brunswick began being blamed for killing critically endangered North Atlantic right whales. An international spotlight now shines on the snow crab fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which recently lost its label as a sustainable seafood.

That leaves the industry — young, growing, lucrative — trapped between value and vulnerabilities. Within this charged atmosphere, business people, scientists and politicians are grappling with what it means to sell this highly perishable, in-demand crustacean into a hungry global maw.

And the future? That’s anyone’s guess.

Birth of an industry

Compared to Atlantic Canada’s centuries-old lobster and cod fisheries, snow crab is in its infancy. Fishermen first reported landing it as bycatch from ocean draggers in the early 1960s.

By 1965, an exploratory fishery using seine nets, suspended vertically in the water, landed 15,000 pounds in Cheticamp, N.S. By 1968 about 60 boats fished for snow crab, primarily around Gaspe, Que., and west of Cape Breton, using large, round baited traps.

Throughout the 1970s, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans gradually introduced management rules, including trap limits, male-only harvesting, minimum mesh size for nets, and restrictions on harvesting recently molted soft-shell crab.

As it grew, the fishery was essentially a free-for-all, limited primarily by how fast and long fishermen could catch crabs and how fast processors could process them.

Fishermen were paid seven to nine cents a pound back then, when meat was painstakingly picked by hand and canned like tuna. (Cans were labelled with whatever brand distributed the meat, which was largely destined for Europe and the United States.)

Later, leg rollers — similar to rollers in old-fashioned washing machines — pressed meat out of legs, along with water blasters that blew meat out of ground-up shoulder sections.

After losing his boat and a season in Alaska, Anastasia moved to New Brunswick, bringing with him knowledge of the more modern processing systems used farther north.

For so-called “frozen sections,” snow crab carapaces were split down the middle into two five-legged sections, each held with a rubber band, cooked, packed into a tray, frozen in brine, and then shipped. Two years later, Anastasia’s company, Orion Seafood, visited Japan with a sample of its product, at the time produced by four plants across northern New Brunswick.

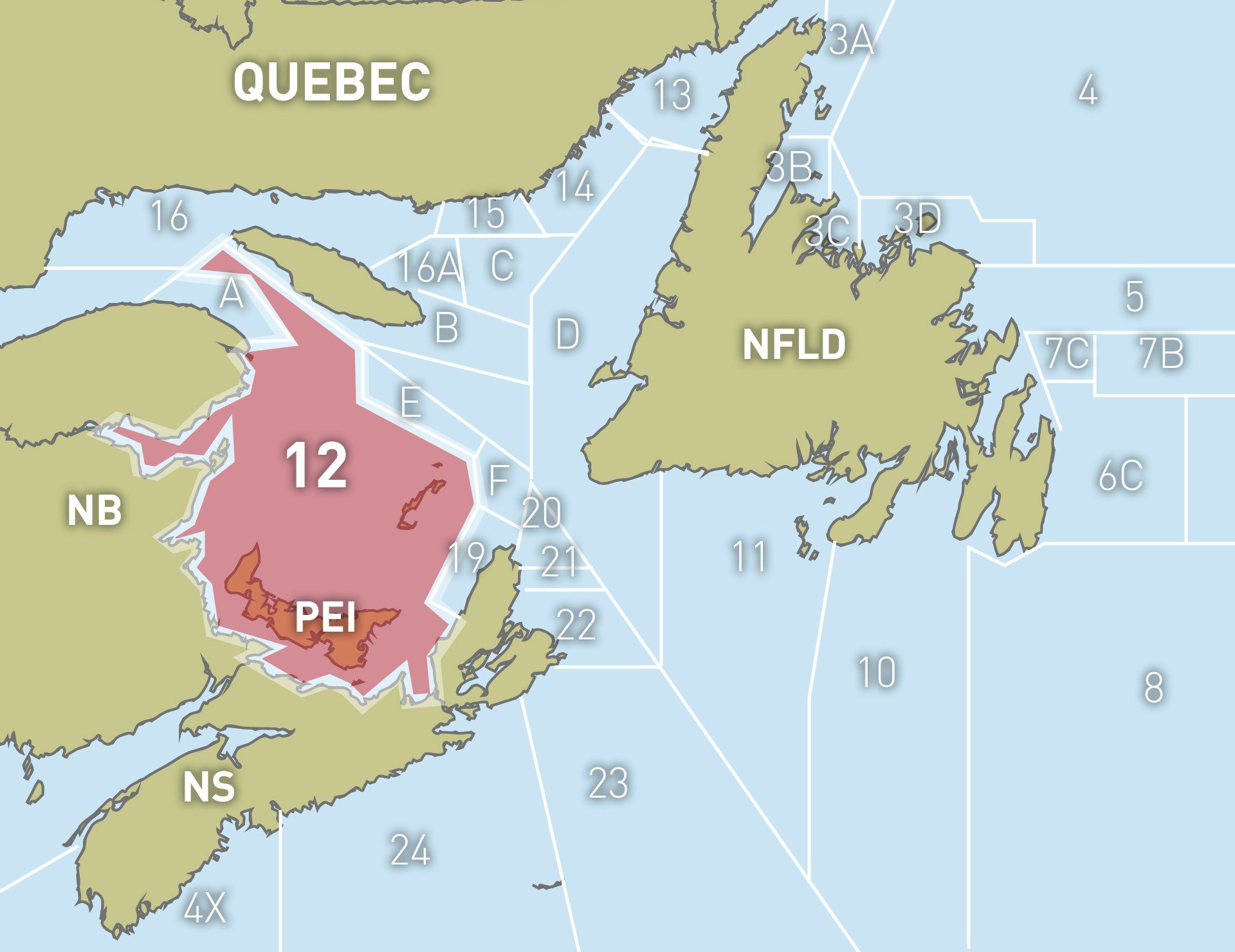

“Gulf product is magnificent,” says Anastasia. Japanese customers go particularly crazy, he says, for the bright-red shell colour of Area 12 snow crab, a harvesting area right off New Brunswick’s northern and eastern coast.

“The two areas in the world that produce the highest-quality crab, when it comes to shell colour and the sweetness of meat, is the Sea of Japan, which only has a 300-tonne quota, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence.”

Japanese buyers were impressed, and after requesting a higher-end gas freezing technology to help preserve the quality and texture of the crab’s sweet, briny flesh, Japan quickly became the primary export market.

In 1982, Atlantic fishermen landed 35,000 tonnes of snow crab, with most of that pre-cooked meat headed to the other side of the world.

“Some of the fishermen were offering me their daughters. They’d never seen money like that.”

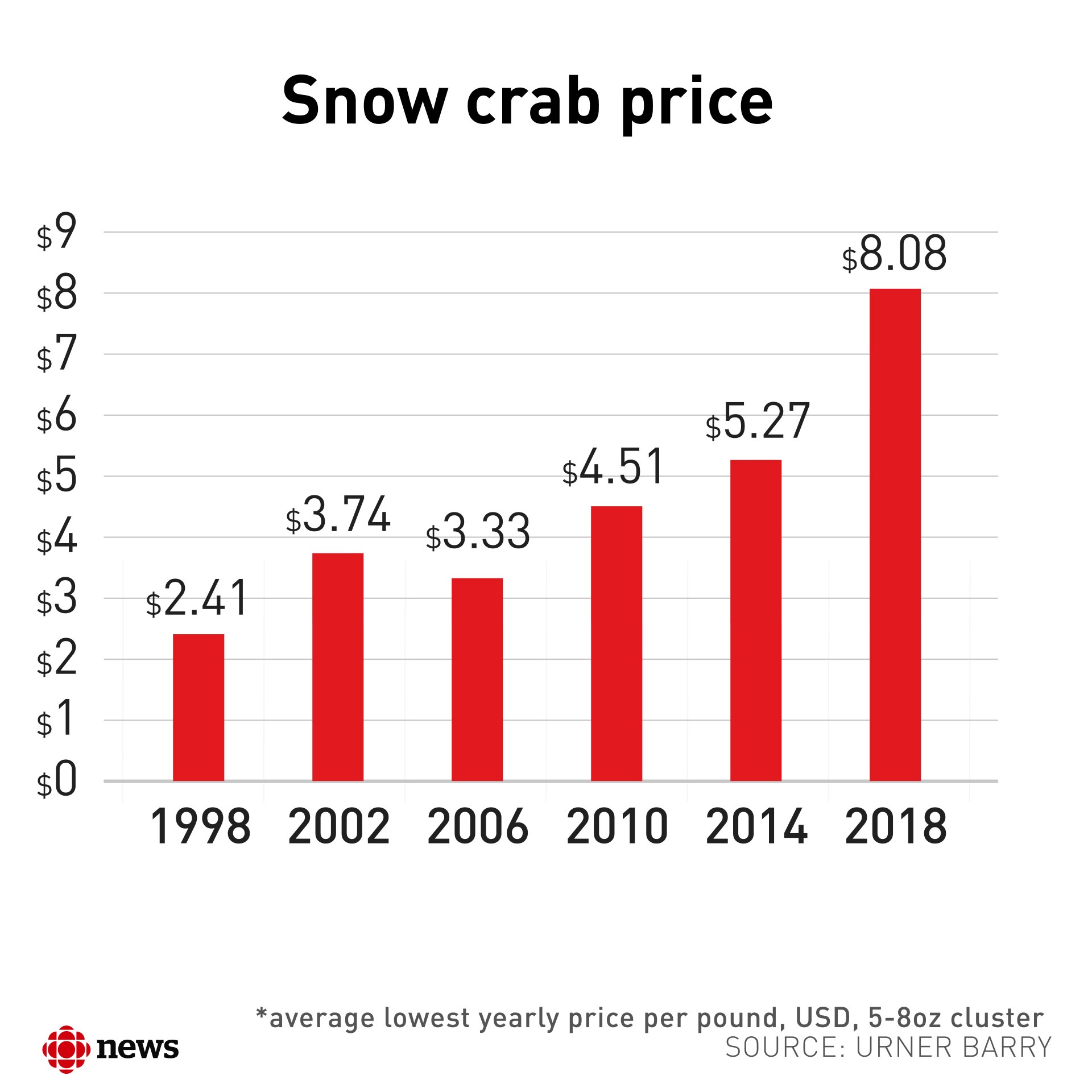

When Alaska closed its snow crab fishery for three years in the mid-1980s, New Brunswick’s crab fishery hit the big time, reaching prices as high as $2 US for fishermen.

“Some of the fishermen were offering me their daughters,” says Anastasia, who has lived in Shediac 100 days a year for 30 years, mostly over crab season. “They’d never seen money like that.”

Two years ago, $129 million worth of snow crab was landed in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick, with the bulk of New Brunswick’s $78 million landed in the northern reaches of this province. That same year, annual snow crab exports reached $280 million, with 83 per cent going to the United States and 12 per cent to Japan.

Less than one per cent stays in Canada, although some is eventually imported back.

These days, most snow crab is flown or trucked to the U.S. south, where all-you-can-eat buffets — particularly in Florida, Georgia and Maryland — use the long, comely legs as a draw.

“I try to get my hands on it as often as possible,” says Lloyd Alford, a seafood distributor based in Apalachicola, in western Florida. “It has everything to do with the taste.”

Listen to "Searching for Snow Crab," the latest episode of The Hook, an original podcast from CBC New Brunswick. You can listen to the full episode by clicking on the CBC Podcasts page or by subscribing in iTunes.

‘On the threshold of total collapse’

Piled with colourful novelty crabs from around the world, Mikio Moriyasu’s filing cabinet, on the ground floor of DFO’s Moncton headquarters, testifies to his more than three decades spent studying the creature.

Hired in 1985, Moriyasu is a crustacean specialist who speaks Japanese, English and French, an asset when dealing with largely French-speaking Acadian snow crab fishermen. He has witnessed the industry’s near-collapse, subsequent recovery and now its newest — and potentially worst — crisis.

In the late 1980s, after years of skyrocketing catches by about 100 licence holders, the gulf region’s snow crab fishery “appeared on the threshold of total collapse,” according to one DFO report. Fishermen blamed a string of bad catches on cold temperatures and ice coverage, but better science was badly needed.

Moriyasu and his team started trawling the ocean floor, counting crabs in each sector to predict what catch, or “exploitation,” levels were sustainable.

Fishermen fought the resulting lower quota; shouting at meetings was common. Fishermen “didn’t really believe the stock was low,” says Moriyasu.

But when the stock plummeted to a record low of 8,000 tonnes in 1989, they reluctantly accepted the new approach, which was deemed a huge success. Moriyasu won a DFO merit award for his work in 1991.

This led to another decade of largely stable catches and good prices.

But another storm was on the horizon.

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Marshall decision gave Indigenous communities expanded rights to fish commercially.

In 2003, four boats, one fish plant and a warehouse on the Shippagan wharf were burned by a mob of angry fishermen, livid at a quota cut from 22,000 to 17,000 tonnes, along with the redistribution of some of that quota to First Nations.

“The mood was hostile,” says Anastasia. RCMP were brought in to quell the riot, while the season suffered the loss of hundreds of jobs and millions of dollars in damage.

While First Nations now actively participate in snow crab fishing and processing — nine Maritime communities hold licences for just under 2,000 tonnes in the gulf region, and Elsipogtog First Nation co-owns Tracadie-Sheila’s McGraw Seafoods — the relationship remains uneasy.

“The concept of the commercial communal licence is one people still have a difficult time wrapping their head around, that it’s not a single individual benefitting,” says Devin Ward, fisheries co-ordinator for Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn, a non-profit treaty rights advocacy group.

“Our communities have less quota for the entire community than most licence holders have in the non-Aboriginal fishery.”

Some individual fishermen in northeastern New Brunswick have 150 tonnes, he says, while Bouctouche First Nation, a community of about 110 people, according to the 2011 census, has only 30 tonnes.

After the violence, as fishermen begrudgingly accepted the new status quo, snow crab catches and quotas started another upward climb — partially because of improved management under Moriyasu. That, paired with rising international demand, particularly from buffets in the U.S. south, led to another decade or so of under-the-radar prosperity in the Acadian Peninsula.

For a second time, everything was going well. But then the whales started dying.

Facing a perilous future

Standing in the wide-windowed wheelhouse of his boat, the Carlo G, Joël Gionet was worried. He first went out on this boat with his father when he was five years old and has caught snow crab for 34 years.

Despite record catches sold at record prices, the past two seasons have been the most stressful he can remember.

Last year, 12 North Atlantic right whales were killed by boat strikes and net entanglements, including snow crab fishing gear, in Canadian waters.

“It was shocking,” says Moriyasu. There are fewer than 450 of the whales left in the world, including about 100 reproducing females, and they’ve been showing up in the gulf in greater numbers.

Last July, two days before the snow crab season was scheduled to end, DFO shut down the fishery for the year.

Gionet vividly remembers hearing about the death of one right whale, entangled in snow crab gear, a decade ago.

“Nobody wants to kill whales,” he says. Now, “all the people from all over the world are looking at us, saying, ‘You’re the guy who killed the whales.’”

The federal government has since introduced strict new management measures, including reduced boat speed limits, mandatory reporting of missing gear, and reductions in the length of ropes allowed to float on the ocean’s surface.

It didn’t help that this year’s weather conditions prevented the season from opening early, despite the best efforts of a Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker. In a failed attempt to clear harbours, the Sir William Alexander smashed sheets of ice in the Bay of Chaleur twice in two weeks this past April.

"If you take the snow crab fisheries, the Acadian Peninsula will die."

The season opened just as an approximately 30 per cent section of Area 12 fishing grounds, where government scientists anticipated whales would appear first, closed on April. 28.

When the Marine Stewardship Council pulled its certification of the southern Gulf snow crab fishery as sustainable earlier this year, Gionet was disappointed but not crushed. Demand and price for their snow crab have never been higher.

The real threat, he says, is the recent closure of a huge swath of the gulf to snow crab fishermen, along with the risk DFO will shut the fishery down early to protect right whales.

“It’s the major industry here,” Gionet says. “If you take the snow crab fisheries, the Acadian Peninsula will die.”

It can be hard, he says, for New Brunswickers who don’t regularly see the product in local grocery stores to understand how important the product is for northern economies. He agrees the availability issue is absurd but attributes it to the eagerness of international buyers.

Each year, his 225,000 pounds of snow crab are pre-sold to a particular buyer at a fixed price before he leaves the dock on his first fishing trip.

“Here, in Caraquet and Shippagan, in June, if you tried to eat a crab leg in a restaurant, you cannot find one,” says Gionet, who spends his winters teaching navigation and fishing at the local community college, as well as in Jamaica.

“There’s crab boats at the dock, but nobody serves crab here.”

Over 10 years, he estimates most captains would gross between $700,000 and $800,000 annually, out of which they pay crew salaries, expenses and boat loans.

In a pinch

As demand increasingly keeps catch out of local hands, one of the only restaurants regularly serving New Brunswick snow crab, says Gionet, is the all-you-can-eat Friday and Saturday surf-and-turf buffet at Casino New Brunswick.

Executive chef Ricky Bernard bought more than 110,000 pounds of the legs last year for more than $1 million. As prices go up every year he says it’s getting harder to make the numbers work.

Bernard says it’s disappointing more snow crab doesn’t stay in-province, which to him is a missed tourism opportunity. If it is important to the community, he says, it should be available here.

But selling to lucrative overseas markets is a genie that’s hard, if not impossible, to get back in the bottle, Anastasia says.

“It’s becoming more challenging for Canadians to have access to it because of the doubling in price and devaluation of the Canadian dollar," he says. Even the company he started, back after his boat hit the ocean bottom, was recently acquired by international seafood giant Chicken of the Sea.

“The Japanese came, they paid the most, and they took [snow crab] with them,” he says. “You have a chance to eat it, but you just have to pay what you have to pay.”

Four years ago, at a conference, a group of Acadian snow crab fishermen asked Anastasia why their catches weren’t more aggressively marketed as a uniquely regional product, like Italian pasta or Colombian coffee. The reality, he says, is that their snow crab already fetches premium prices abroad without it.

The same week, when a new seafood restaurant opened across the street, the marquee item was snow crab — from Alaska.

“In Moncton,” says Anastasia with a sigh, shaking his head. “That pretty much tells it all.”