Sammy Sampson strokes his clean-shaven chin as he gazes anxiously at the computer screen, waiting for the Skype call to connect.

He'd gotten rid of his beard just that morning.

“I wanted him to recognize me,” the former soldier explains.

The chime sounds. “Hello,” a faraway voice calls.

“Hello, Sammy,” Sampson responds.

“Yes, hello!”

“Hello, muraho!” Sampson shouts, using the Kinyarwanda greeting he learned all those years ago.

A streak of grey pixels flashes across the monitor, finally giving way to a smiling face.

“Hello,” the other Sammy says, grinning broadly from 11,000 kilometres away from where Sampson sits in Ottawa. Sammy Tuyishime congratulates the older man for remembering the language.

Sammy Sampson laughs out loud and slaps the table.

“Look at you!”

The call has reunited two men who not only share a name, but also a history. Both are survivors, each in his own way, and each has a story to tell after more than two decades apart.

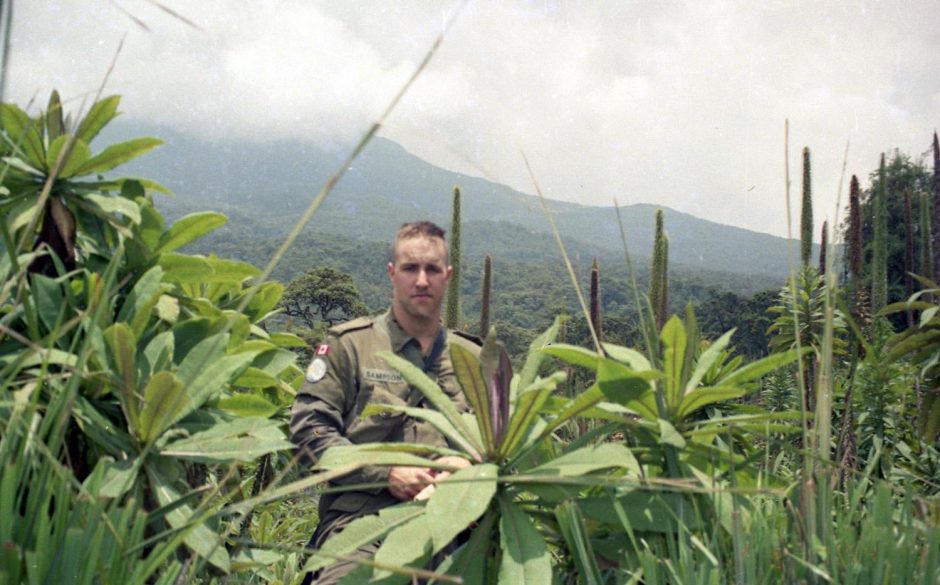

In 1994, Sammy Sampson was a 24-year-old Canadian soldier on his way from CFB Kingston’s Signals Regiment to Gisenyi, a city on the north shore of Lake Kivu in Rwanda.

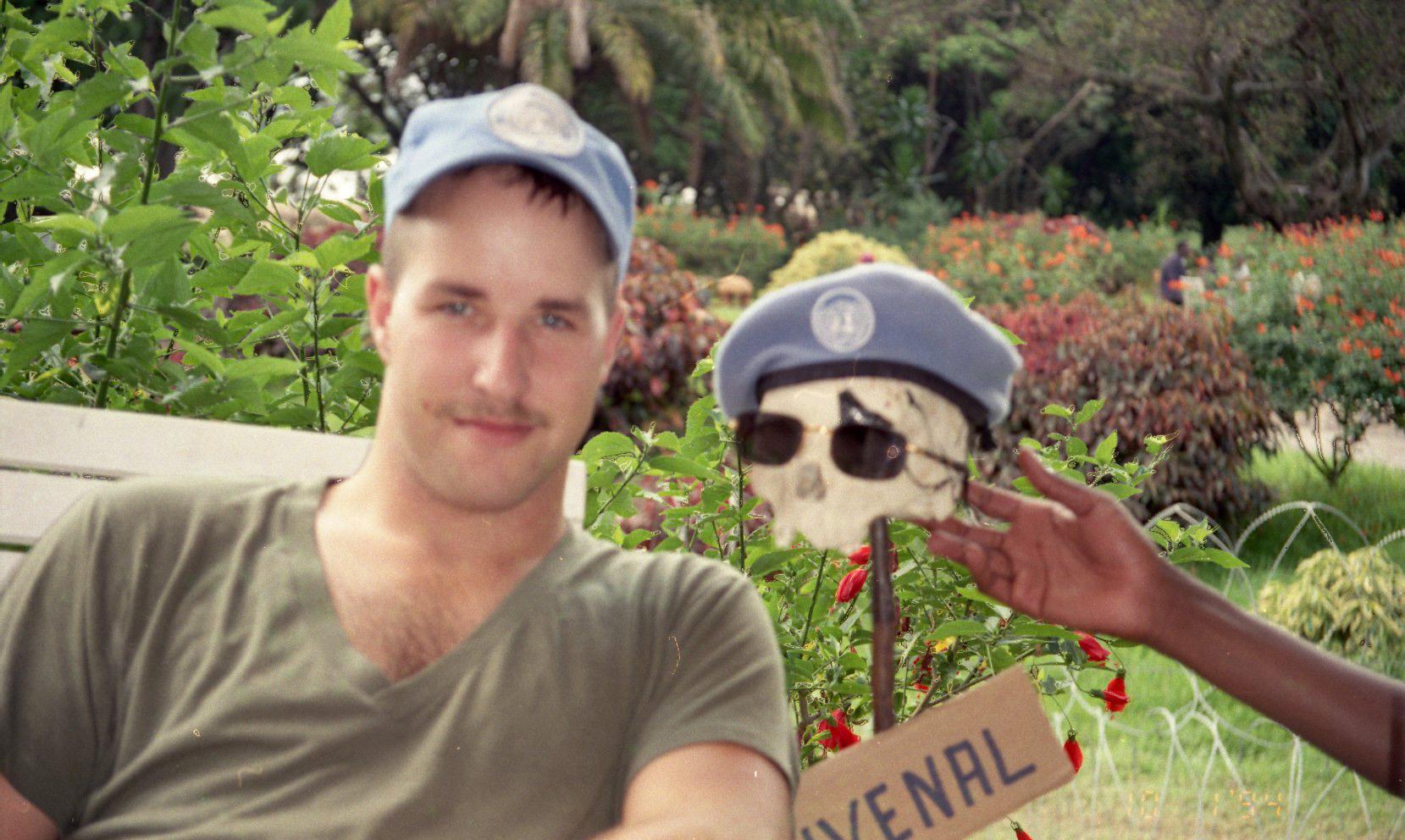

Gisenyi had been the seat of the provisional government during the Rwandan genocide, when 800,000 people were butchered over a 100-day period, from April to July.

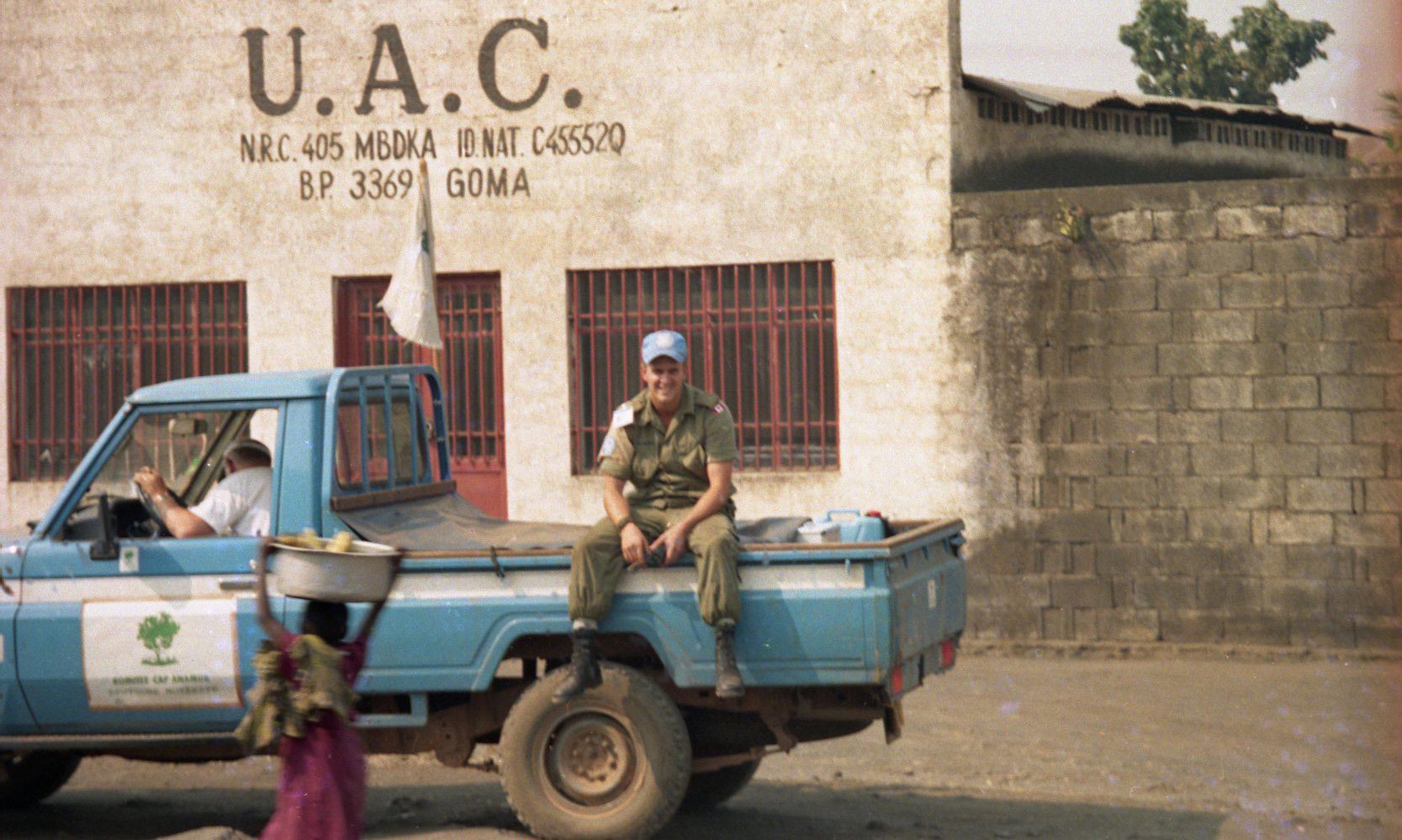

Sampson was among the 400 Canadians taking part in Operation Lance, and arrived in Rwanda as part of the advance party for an eventual force of 5,000 UN-approved soldiers.

The Canadians were among the first outsiders to witness the brutality of the genocide, and face the contempt of its survivors.

“When we showed up, we were the people that had to apologize for the world,” recalled Sampson, now 48.

“We were the white faces that the people of Rwanda felt had let them down.”

Sampson had enlisted at 17, and had already served in Iraq and Kuwait. He would go on to deployments in Haiti, Bosnia and Afghanistan.

But it was the Rwanda mission that left the deepest scar.

Nowhere else had Sampson witnessed brutality so extreme. The suffering of the country’s children, in particular, left a profound mark.

The image of sick and dying kids pleading for help — help he was often unable to provide — will always stay with him.

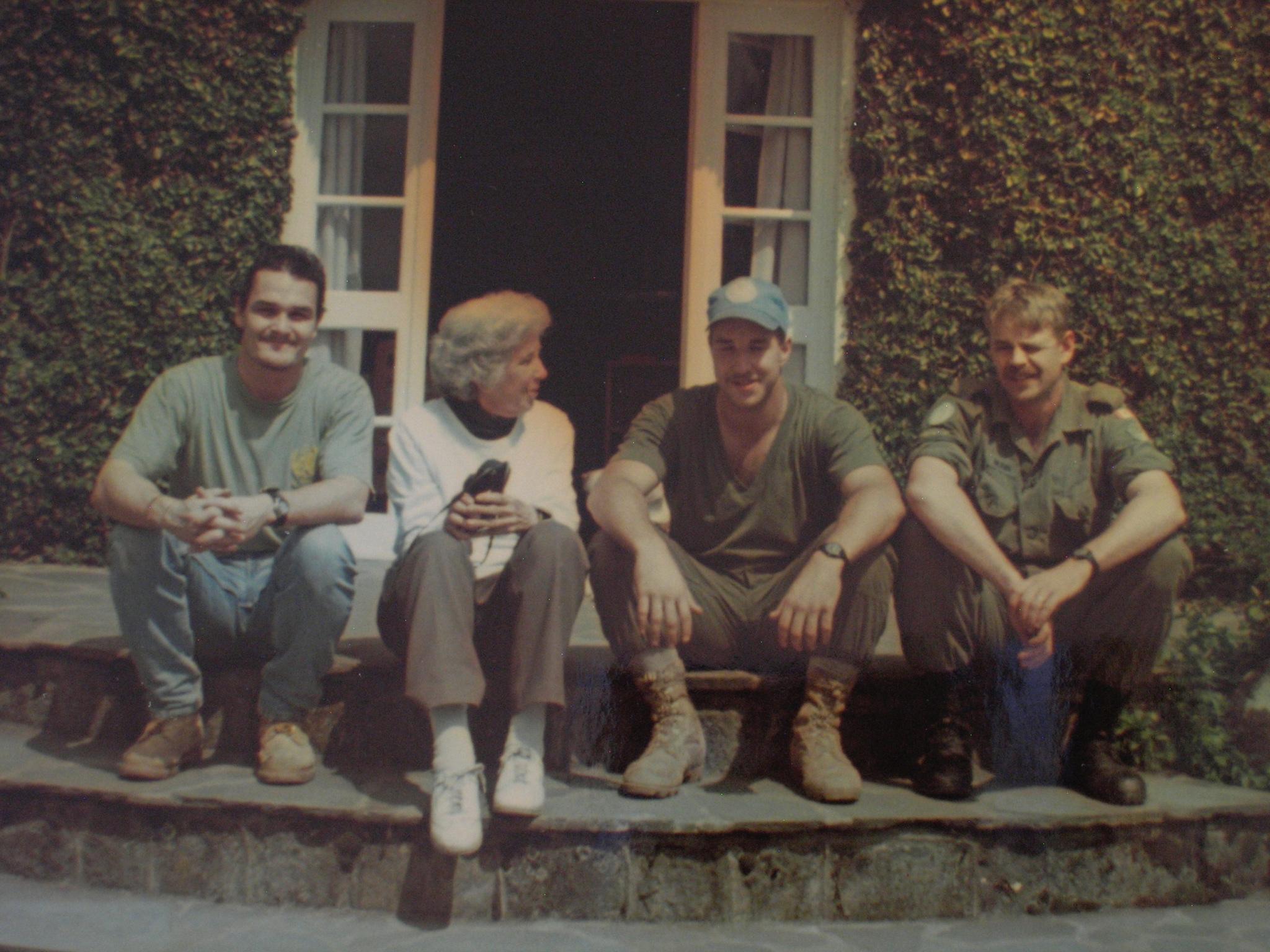

A key ally during his unit’s time in Rwanda was an 82-year-old American woman named Rosamond Carr, who lived by herself at the edge of the Gisenyi jungle.

Carr had come to Rwanda decades earlier, and had converted a plantation into a flower nursery. In the 1960s, she struck up a friendship with pioneering mountain gorilla preservationist Dian Fossey.

Carr had even been portrayed by Julie Harris in the 1988 Sigourney Weaver film Gorillas in the Mist.

But six years later, Sampson and his comrades were feeling anything but starstruck. In fact, he recalls feeling angry with Carr over her refusal to leave the plantation despite having very little protection.

One day Carr summoned the Canadians to ask them to help protect a population of nearby mountain gorillas, left vulnerable by the fighting.

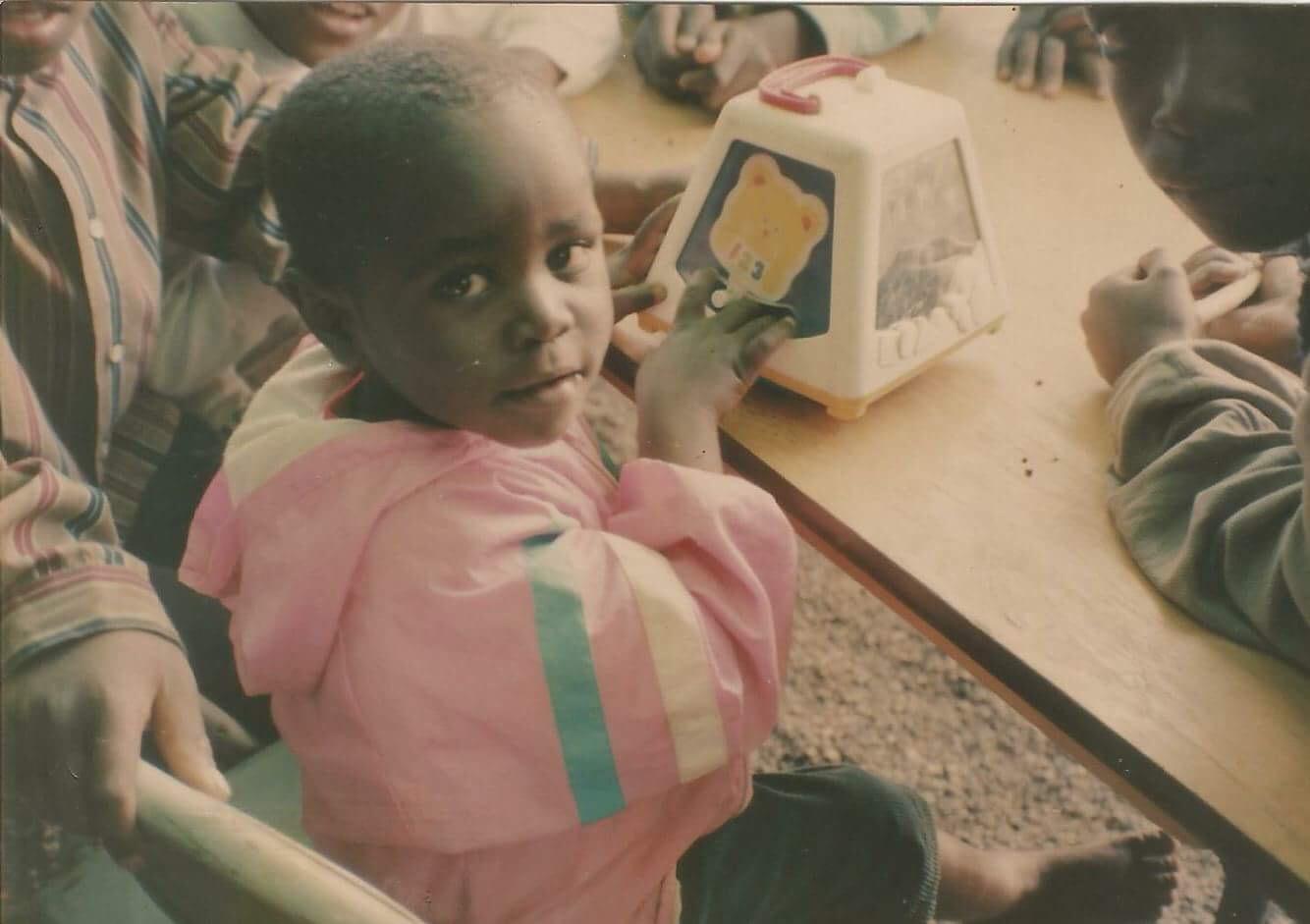

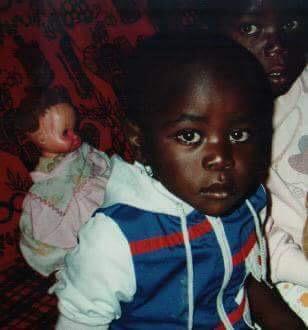

As they spoke, small children surrounded the soldiers. Most had been orphaned in the genocide, and many had seen their parents murdered. Some had survived only by hiding under the corpses of their families.

Carr had decided to convert a cavernous, brown brick plantation building into a home for the orphans. Sampson and his section of six Canadians began assisting her, sometimes even borrowing supplies from the Canadian mission headquarters in Kigali.

They also brought children to Carr and the orphanage she called Imbabazi. The gut-wrenching decision about which kids to save and which to leave behind often fell to Sampson.

“As a corporal, you’re making life and death decisions about who gets to live, who doesn’t,” he said.

“It attacked my morals and ethics. I’m a Canadian. You don’t leave kids crying, abandoned in the middle of the street. You pick them up and take them somewhere. I left them because I had no choice.”

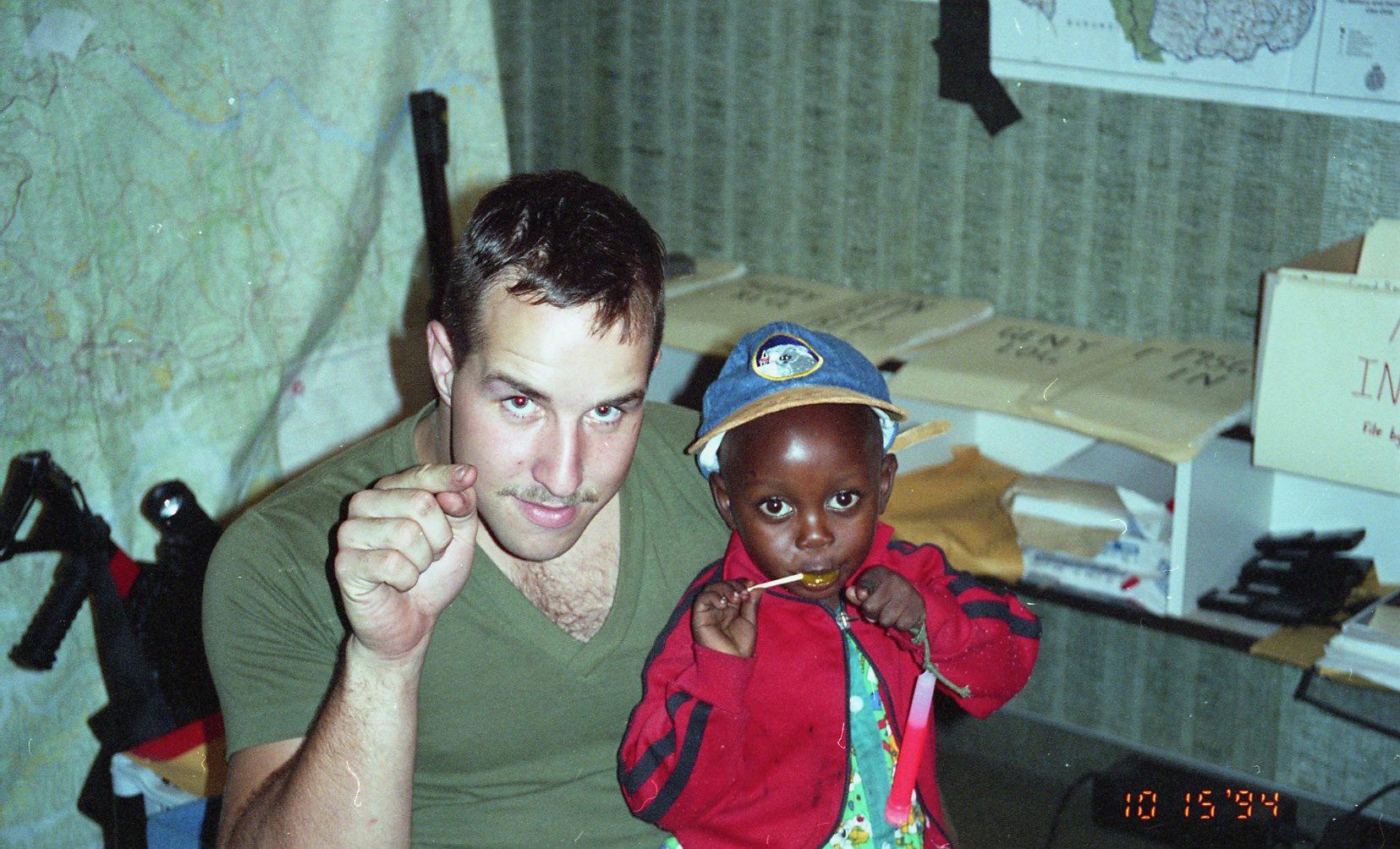

One orphan took an immediate shine to the tall, muscular Canadian. The four-year-old boy introduced himself to Sampson by wrapping his arms around the soldier’s leg.

Sampson tried to shake the boy off.

“But then he had the audacity to grab it again, and all the kids started laughing... This little fella didn't care whether I was a big white guy with a machine gun, he didn't care what I represented, he didn't care [about] anything. I was an oddity, and he grabbed my leg and that was it."

Over the weeks that followed, the soldier and the little boy would single each other out whenever Sampson's unit visited the orphanage.

The boy, who spoke no English and had no known name, would occasionally tilt his head, squint his eyes and jab a finger toward the soldier. Sampson responded by cocking his own head and pointing back.

The two soon formed a special bond.

Sampson found spending time at Imbabazi and playing with the children there was as close as he could get to feeling normal.

"It was the only place in Rwanda where I could let my guard down," he said. “I could actually become a human being for a short period of time with these kids."

After spending time in other parts of Rwanda, Sampson returned to Gisenyi in December. That’s when Carr told the soldier that the boy had been named Sammy, after him.

“Nothing like that had ever happened to me before,” he said.

The mission came to an end and the Canadians left Rwanda in early 1995.

Ethnic violence soon flared up again in Rwanda as Interahamwe, a Hutu paramilitary organization, flooded into Gisenyi.

Sampson, who was by then on a UN mission in Haiti, heard the reports and assumed the worst about the children at Imbabazi.

“While Mrs. Carr might have made it, I [couldn’t] really see a situation where any of these kids could have survived.”

That included little Sammy.

"He got my name, and I got a lifetime of memories. And guilt. And shame."

For 23 years, Sampson has struggled with the belief that he’d done nothing to help the people of Rwanda, and the guilt and sadness that accompanied that conviction — especially when he thought about the children he’d left behind.

On subsequent missions, that guilt would intensify whenever he saw a small black child.

When his own daughter was born six years ago, Sampson suffered a breakdown. In the intimate space of new fatherhood, he was suddenly confronted with the innocence and fragility of childhood.

He was unable to shake the profound guilt he felt over his failure to help some of the children he’d seen suffering in Rwanda.

Sampson was eventually diagnosed with PTSD. His marriage broke down. He lost his job. He had become a residual victim of the genocide.

Sampson could never find the courage to discover what had happened to Imbabazi. In late 2017, Sampson's girlfriend, Susie Kingsley, decided to find out for him.

Kingsley discovered that the orphanage had not only survived the genocide’s violent aftershocks, but had flourished.

She learned that since its start in 1994, Imbabazi has cared for more than 400 children. The orphanage has won international awards and been the subject of several films, including a 2008 BBC feature in which Sigourney Weaver returns for a visit.

Imbabazi became a model orphanage, replicated by others across Rwanda and beyond.

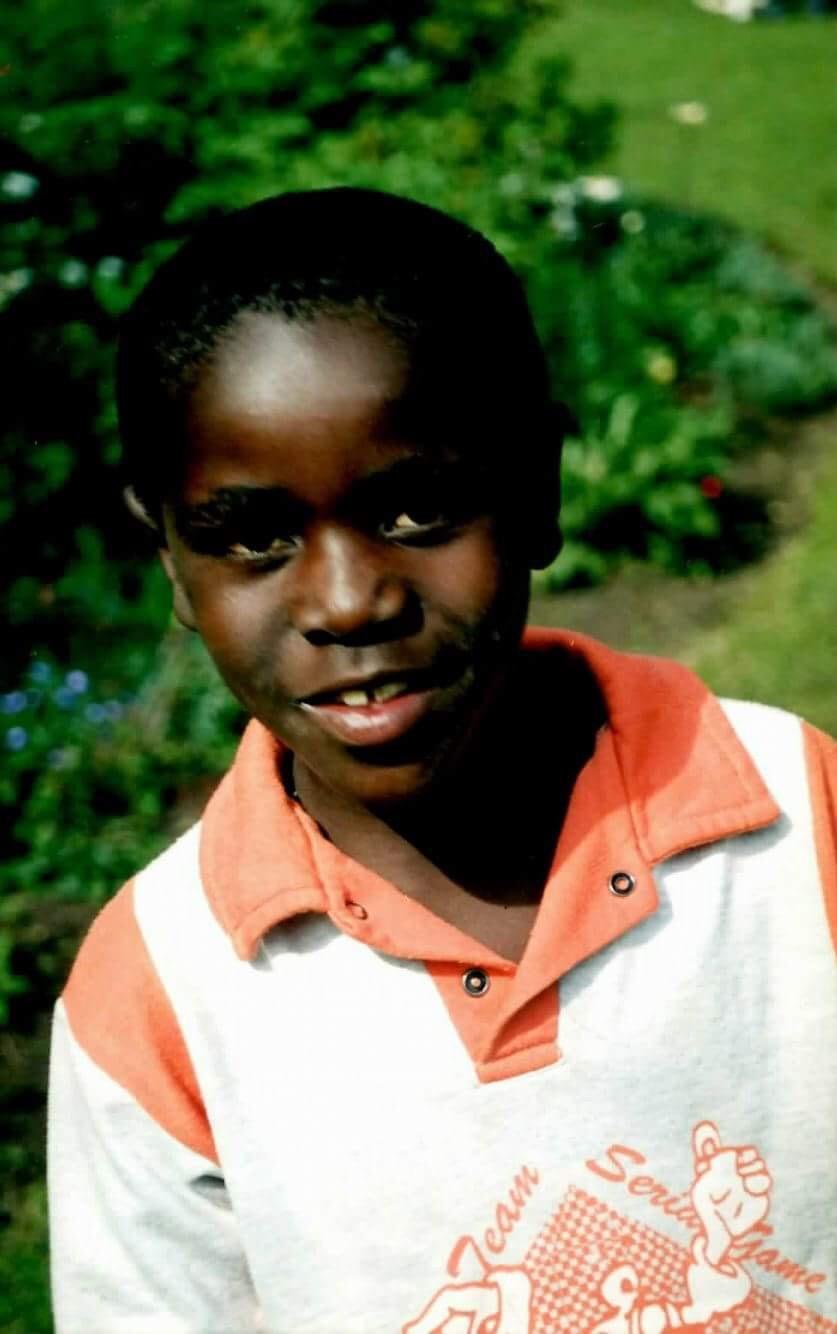

Not only that, but Imbabazi’s original orphans have survived. Several had grown up to become lawyers, doctors, politicians and teachers.

Kingsley ended up locating a Sammy Tuyishime on Facebook, and convinced Sammy Sampson to message him.

"What did Mrs. Carr tell you about your name, so I know it's really you?" Sampson asked.

"There were UN soldiers.... Among those soldiers, there is one who looked [after] me and loved me so much and gave me his name, Sammy," Tuyishime replied.

"And I am that man," Sampson wrote.

The 19 original Imbabazi orphans consider themselves a family, and stay connected through Facebook.

Once a year, they pile onto buses and gather at Imbabazi to commemorate Rosamond Carr, the woman Tuyishime calls "our lovely mother."

Tuyishime, now 28, operates a successful company in Kigali that takes tourists on excursions to see the city’s landmarks and museums, and even offers face-to-face encounters with mountain gorillas in Rwanda’s national parks.

The tall, lightly bearded man smiles at Sampson through the computer screen in Ottawa, white earbuds in his ears.

“I am in the city centre,” he tells Sampson. “I would like to show you our beautiful city now.”

Tuyishime swivels his phone to reveal tall, modern buildings.

For the Canadian veteran, this glimpse of a bustling yet peaceful city is a powerful sign of hope. So is the sight of the friendly young man who carries his name.

"I have thought about you for 23 years," Sampson tells him.

For veterans of the Rwanda mission, often forgotten or wished away, the success of the Imbabazi orphans has shone a new light on Canada’s role there.

“Canadians did good work in Rwanda, but they are forgotten,” Sampson said. “If we could just stop and a take a look at the positive things we accomplished.”

Sampson has started a fundraising campaign to bring Tuyishime to Canada for a visit.

In just a few weeks, with support from fellow veterans of Operation Lance, he has nearly reached his goal of $9,900.

He and some of the other vets are also planning a visit to Imbabazi next year.

It’s a return journey he never thought he’d make, a reunion he never thought he’d experience and a personal reconciliation that has evaded him since he left Rwanda.

"I am so proud of you, Sammy," Sampson tells the young man smiling at him from the computer screen.

"I am proud of you, too," the young man responds. "Even though it is not possible for everyone to understand that, for sure you did a lot."

Overcome, Sampson covers his face with his hands and remains silent for a long time while Tuyishime looks on, still smiling.