September 12, 2020

As March moved into its second week, it began to shed the blanket of the winter months and bring the scent and hope of spring to Winnipeg.

People had a pent-up desire to get out and gather with friends, to visit a patio under the warming sun.

There was little indication those plans would be put on an indefinite hold.

“Six months ago feels like a decade. It is just astounding all the trials and tribulations we've gone through,” said Jason Kindrachuk, an assistant professor of viral pathogenesis at the University of Manitoba and Canada Research Chair in emerging viruses.

“COVID-19 has inevitably changed our history. Within a few months of its emergence our social norms and behaviors have been altered for the foreseeable future. But we have also seen that we are extremely adaptable.”

Since January, health officials around the world had been closely watching an outbreak of a novel coronavirus in China, and by the end of February cases also began surging in Korea, Japan, Singapore and Italy.

The World Health Organization had declared a public health emergency of international concern and called for active monitoring and preparedness in other countries. The first Canadian case of the newly named COVID-19 (for coronavirus disease 2019) was reported by Health Canada on Jan. 25, in a Toronto man who had returned from China.

Still, most Manitobans went about their daily routines.

“First, there was that initial bit of denial — ‘oh, it's not coming to Manitoba.’ And then, you know, a bit of fear,” said Shauna MacKinnon, chair and associate professor in the department of urban and inner-city studies at the University of Winnipeg.

In early March, there were no known cases in the province and the chances of contracting the illness here were still labelled as low by local health officials.

Within days, everything changed.

Worldwide, the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths surged, leading the WHO to declare it a pandemic on March 11.

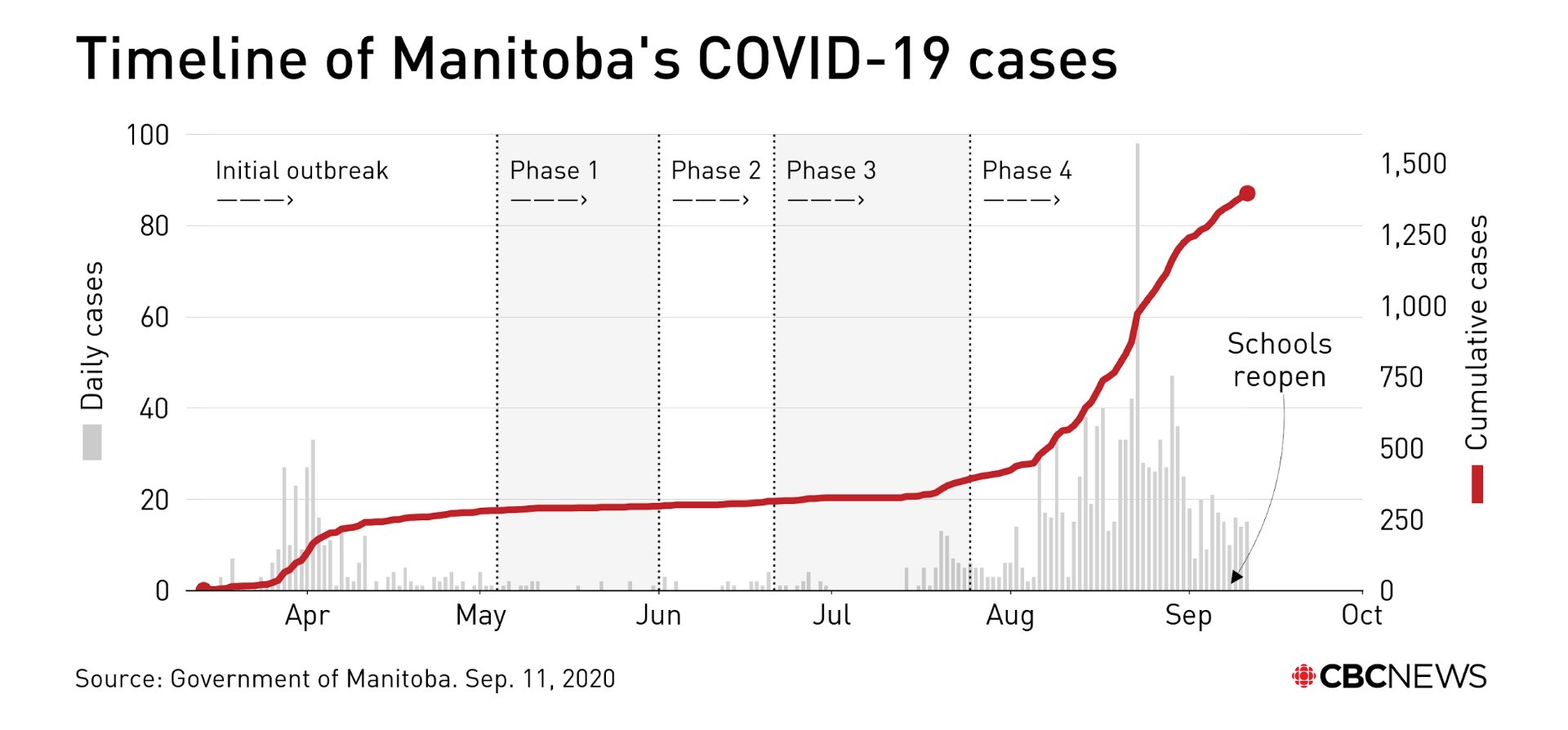

The next day, Manitoba announced its first case. Two hours later, it added two more. It also announced the number of people being tested had soared from 40 in a day to 500.

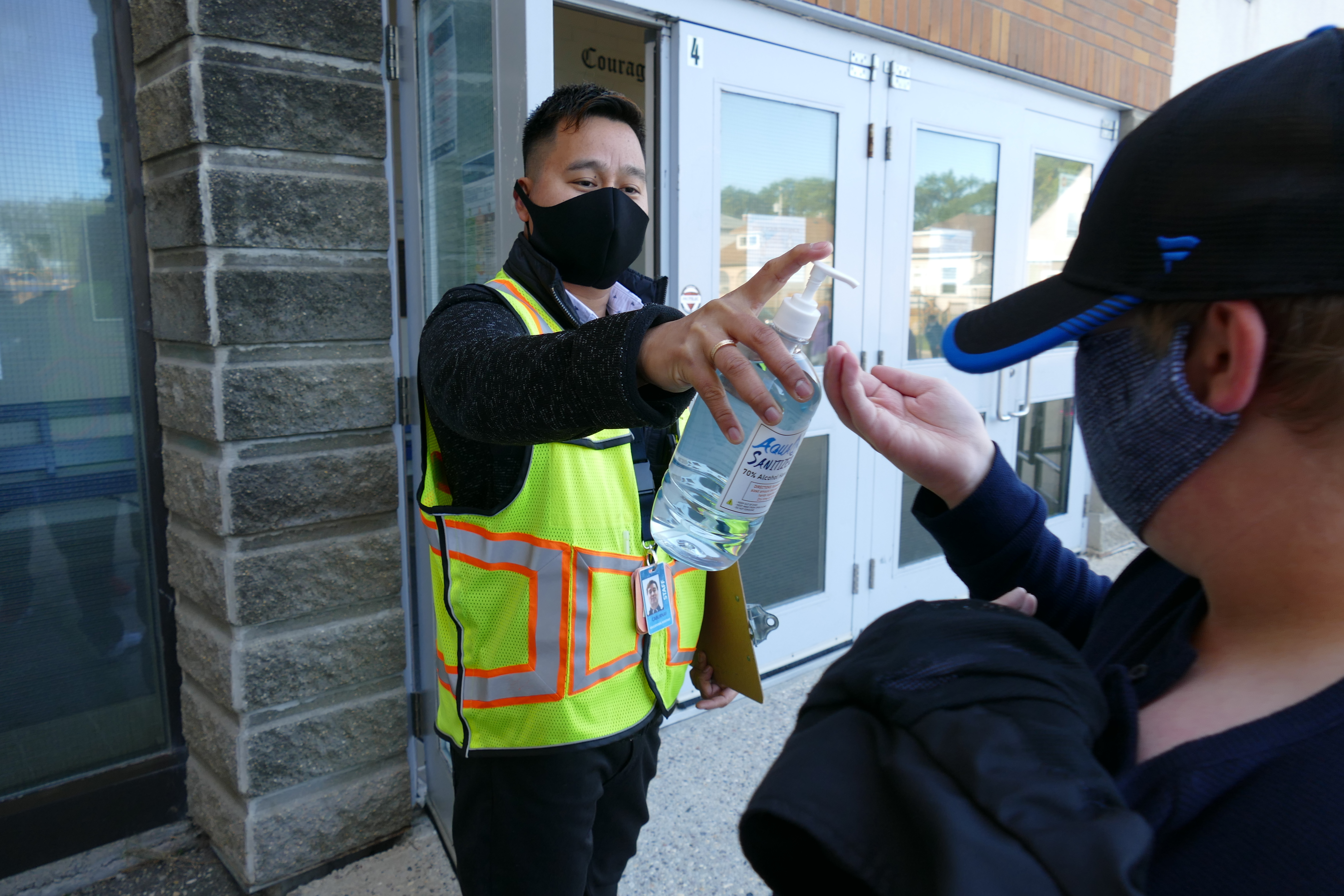

Stocks of hand sanitizer and toilet paper vanished from store shelves as fear took hold and people hoarded.

Then the dominoes really tumbled. Professional sports teams suspended their seasons and an avalanche of cancellations followed, reaching the amateur and community levels.

Stores, museums, galleries, schools, government offices, stage productions, movie theatres, restaurants, places of worship, therapeutic and medical services, hair salons, festivals, flights, non-urgent surgery and diagnostic procedures were shut down or drastically scaled back.

The province pushed hard on physical distancing and stay-at-home messaging, suspending all visits to seniors' homes to reduce the risk of spreading the virus.

Winnipeg, like other communities, fell silent.

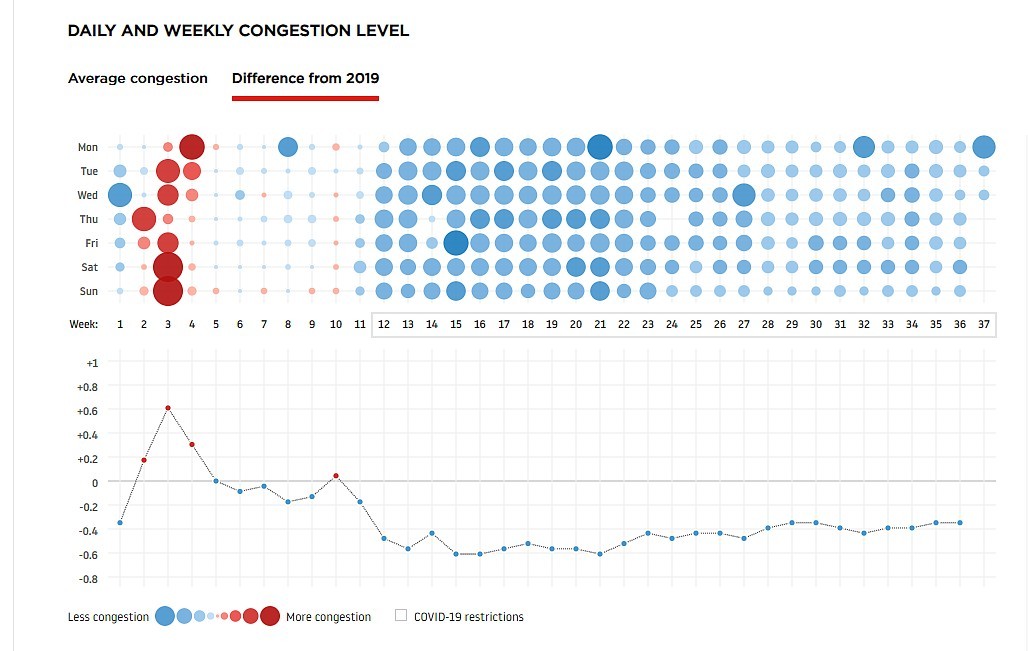

Traffic measurement company TomTom recorded a weekly congestion drop of 35 to 60 per cent in Winnipeg compared to 2019 that started the week after the first case and continues now.

“It was almost like the city had gone to sleep and forgot to wake up,” said Duncan Mercredi, a Cree-Métis poet and storyteller named as Winnipeg’s poet laureate in March, just as the pandemic hit.

“As a writer, I like to walk, to see people, observe what they're doing. And all of a sudden there's nobody there. I'm looking at the cats wandering the streets. That was really kind of eerie.”

The laureate creates work that reflects the life of the city and the 69-year-old Mercredi has compared Winnipeg's muted tenor to the isolation of northern Manitoba, where he used to be a surveyor.

“You’re in the bush, you know, there’s very few people. And yet, in a city with over 700,000 people I had that same feeling,” he said.

“When the pandemic first started there were very few cars, very little construction going on, very few buses going by, no children laughing outside or playing outside.

“You're standing outside at 10 p.m. and there's nothing, absolutely nothing.”

To encourage people to get outside, the City of Winnipeg closed some streets to vehicles, turning them over to physically-distanced pedestrians and cyclists.

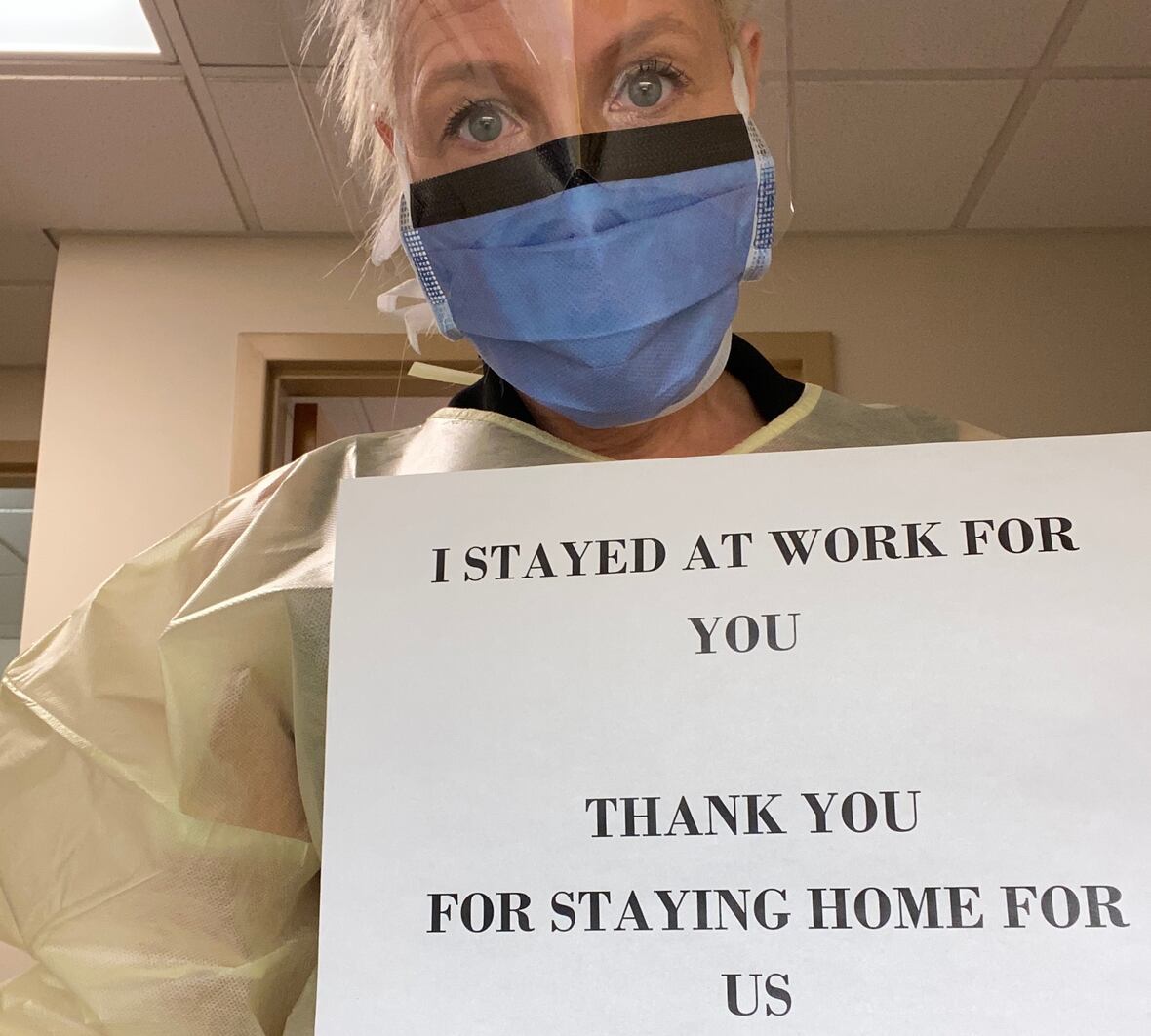

Signs thanking essential workers, including those in health care, popped up in windows, while health-care workers urged the public to "flatten the curve" by staying home to prevent the spread of COVID-19."

Other businesses deemed essential soon became the scenes of long lineups as people worried about supplies running low. With limits put on the number of customers allowed in at any one time, lines often snaked out through parking lots.

Inside, shoppers were met with a new reality of space markers — arrows on the ground directing which way to travel, and stickers marking where to stand while in the cash line, ensuring a two-metre distance.

Another new reality set in March 19 when public health officials announced the first person to be hospitalized with COVID-19 and that a 30-bed isolation unit would be created at the Health Sciences Centre.

As the seriousness of the situation set in, the provincial government put a 30-day supply limit on prescription to prevent the stockpiling of medications and ensure a continued supply for everyone.

On March 20, the province banned gatherings of more than 50 and declared a state of emergency, giving the government the ability to prosecute people or businesses that refused to comply.

Anyone breaking the orders risked a fine up to $50,000 or six months in jail, or both.

"This is not something we take lightly. We respect the individual rights and freedoms of all our citizens," said Premier Brian Pallister, who encouraged people to boycott businesses not complying, while announcing fitness centres, bingo halls and casinos would also close.

By March 23, domestic travellers arriving in Manitoba were urged to self-isolate for 14 days — the notion of low-risk long since discarded by government and health officials.

"The risk to Manitobans is real, since all of our cases have been imported from travel," Dr. Brent Roussin, Manitoba's chief public health officer, said at the March 23 COVID-19 briefing, a daily practice that began with the first case.

While other provinces reported new cases being spread through community transmission — where the source of infection is not known — Manitoba boasted that all of its cases could be traced, which meant the virus could still be easily tracked.

Community transmission, Roussin said, was a more worrisome sign.

It's one that would come later for Manitoba.

In-school classes end

The COVID-19 numbers continued to climb through March, with the province's first daily double-digit jump on March 25, when 14 new cases brought the total caseload to 35.

The daily cases rose by 25 on March 28 and another 24 on March 30.

Meanwhile, in what was called a proactive response against the spread of COVID-19, the province announced on March 13 that classes would be cancelled for a week before spring break and one week after, leaving students out from March 23 until April 13.

They didn’t return.

On March 31, Education Minister Kelvin Goertzen cancelled in-school learning indefinitely. He encouraged students to continue online-based learning from home, but that was met with mixed success.

Some families struggled with new child care realities while others faced barriers such as the inability to afford a home computer that made remote learning impossible.

When the province announced that grades would go no lower than what they were before the classes were suspended, many students just gave up on school for the remainder of the year.

COVID-19 laid bare certain inequalities that affect how people experience the pandemic, says MacKinnon.

“If you come from a more affluent situation, your experience is not going to be the same as a low-income person living in an apartment with overcrowded conditions,” she said.

“The critical thing for us now is looking at what we have learned that we can carry through to improve the situation for others. If we can do something like that, then we will have all been worth it, in my view.”

First death

Manitoba’s first COVID-19-related death was announced March 27 — a Winnipeg woman in her 60s, who had been admitted to an intensive care unit the previous week.

Ramping up preventive measures, the province announced the same day that public gatherings would soon be limited to 10 people. It also launched an online counselling program for people dealing with anxiety related to the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the City of Winnipeg ordered play and picnic structures closed. That followed the same move days earlier by the Manitoba Schools Boards Association, which posted off-limits signs on play structures and surrounded them in yellow caution tape and removed swings.

That same week, the federal government barred visitor access to national parks, which meant Winnipeg’s popular Forks Marketplace was locked up.

Health workers get sick, deaths spike

As the calendar flipped to April, the situation in Manitoba became more severe.

Four nurses at Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre tested positive for COVID-19 following an exposure that forced roughly 100 health-care workers to isolate at home for two weeks. The Manitoba Nurses Union later said HSC management was aware of one exposure by March 20, but waited 12 days to send workers home to isolate.

An epidemiology report, which was completed in July but only became public in September, revealed two patients died in the outbreak, which infected 16 staff members, five patients and four close contacts.

The case numbers in Manitoba soared, with 24 announced on April 1 and 40 the following day, bringing the total number of cases to 167 and more than 11,000 people tested.

Then the deaths began to climb:

- April 3 (a man in his 50s).

- April 7 (man, 60s, linked to the HSC outbreak).

- April 10 (man, 70s).

- April 15 (woman, 60s, linked to the HSC outbreak.).

- April 20 (woman, 80s).

The province announced new public health orders for anyone travelling outside the province — including within Canada — to self-isolate for 14 days when they returned.

It also restricted travel north of the 53rd parallel and into remote communities.

Demand for hand sanitizer and personal protective equipment grew and the province issued a call for local businesses to make and supply needed medical supplies to help in the fight against coronavirus.

Distilleries, brewers, and even the Royal Canadian Mint responded.

Plan to reopen economy

May brought about a slight pivot in the province’s fortunes.

When the month started, Manitoba had 279 cases. When it ended, there were 295, an increase of just 16. And that was in spite of a jump in testing.

At the start of May, 25,402 tests had been completed. By the end, the number was 43,886. The province expanded testing to anyone showing symptoms and dropped the need for a referral.

Pallister said he wanted a clear sense of the spread of the coronavirus in the province before businesses and services closed by the pandemic could begin reopening.

Most of the new cases were related to the province’s second COVID-19 cluster. The outbreak of 10 cases was identified at a Brandon trucking company, Paul's Hauling.

The month was also marked by the announcement of a seventh death on May 5, involving a man in his 70s.

After three months of the economy struggling through a shutdown, Pallister announced a number of non-essential health-care and retail businesses would have the option of reopening under strict guidelines.

He and Roussin repeatedly praised Manitobans for doing their part — listening to public health orders, staying apart, staying indoors — and flattening the curve.

Manitoba’s caseload was among the lowest in the country, save for Atlantic Canada and the territories.

Expanded reopening

The slow pace of cases continued through June. Although the monthly total of 30 new cases nearly doubled that of May, the highest single-day jump in June was just four.

Pallister expanded the province's reopening plan with its second phase, allowing most businesses forced to shutter earlier in the year to reopen. The plan included expanding capacity at child-care centres and allowing restaurant dining rooms, bars, brew pubs and microbreweries to open at 50 per cent capacity.

Health officials also announced that hospitals could start allowing more visitors, loosening a ban on visitors at all acute-care facilities that allowed only a few exemptions.

The province moved into Phase 3 of the reopening plan on June 21. Gathering sizes increased to a maximum of 50 people indoors and 100 outdoors, from the previous limits of 25 indoors and 50 outdoors.

The 14-day quarantine was lifted for people coming from Western Canada and northwestern Ontario (west of Terrace Bay), daycares were allowed to return to full capacity and day camps were allowed to have up to 50 kids per group.

Pandemic roars back

By July, it felt like the plague had evaporated from Manitoba.

The month started with a 13-day stretch that saw not a single new case. Until then, the province had not gone more than six clear days.

Even better, there was just one active case and no one in hospital with the illness.

Then the bottom dropped.

On July 14, five new cases, all people in hospital, were announced. By the end of the month, there were 70 active cases and another death — a man in his 70s whose death was announced July 28.

Another outbreak was identified, this time linked to Hutterite colonies, where there were at least 35 cases. The province soon stopped identifying when cases were connected to the colonies, after Hutterites endured stigmatization due to the outbreak.

As the case numbers grew, so did the worry.

People flocked to COVID-19 test sites, breaking single-day records on multiple occasions. Many were turned away from drive-thru sites that reached capacity within hours of opening.

Through July, 25,312 tests were completed, by far the most for a single month.

Despite that, Pallister continued to promote tourism to the province, saying Manitobans shouldn't live in fear.

By August, the pandemic was stronger than ever with the province twice setting single-day records for new cases — 42 on Aug. 22 and then 96 the next day — and six deaths.

The total number of cases surpassed 1,000 by the last week of August, and the number of active cases reached 469 by month’s end.

Manitoba also saw its worst outbreak at a personal care home, which infected 13 people and claimed four lives. Two people at Bethesda Place care home in Steinbach died in August and two more in early September.

The deaths pushed the province’s coronavirus-linked fatalities to 16.

Bethesda's wasn't the only outbreak. Five other personal care homes, including four in the Brandon area, had at least one person test positive.

“From a Canadian perspective, this pandemic will certainly be remembered for the disproportionate and heartbreaking toll it has taken on our most vulnerable in long-term care,” said the U of M's Kindrachuk.

An outbreak also hit the Maple Leaf Foods pork processing plant in Brandon, where 70 workers fell ill.

'The province got a little cocky'

The spike in cases led to heightened restrictions in western Manitoba’s Prairie Mountain Health region, where mask mandates and steep fines for rule breakers were imposed by the chief public health officer.

Roussin explained he needed to crack down on the spread "before things get out of hand" in the southwestern part of the province. That meant returning to measures that hadn't been in place since the early months of the pandemic.

Roussin suggested people had let down their guard after July’s extended run without new cases and were losing track of "fundamentals.”

"I think the province got a little cocky — not just the people themselves, but even the government,” said poet laureate Mercredi. “Like, ‘look, we're doing a great job so we can go ahead and do what we used to do before.’”

Esyllt Jones, a professor of history and community health sciences at the University of Manitoba, believes it also has to do with threadbare patience.

“The extent of the lockdown has been pretty unprecedented in the modern era. Everybody’s been as good a sport as they could've been, but for some people it's financially damaging and it's also difficult for children, so it’s hard to sustain that,” she said.

Positivity rate, community transmission

The once-enviable position Manitoba had among all provinces early in the pandemic was lost in August.

The five-day positivity rate — a rolling average of the COVID-19 tests that come back positive — went from zero in July to 3.1 per cent by the end of the month.

Manitoba became the country's leader in active cases per capita as community transmission arrived.

On Sept. 3, Roussin declared 20 per cent of Winnipeg's active cases to have no known transmission chain, a statistic he repeated on Sept. 10.

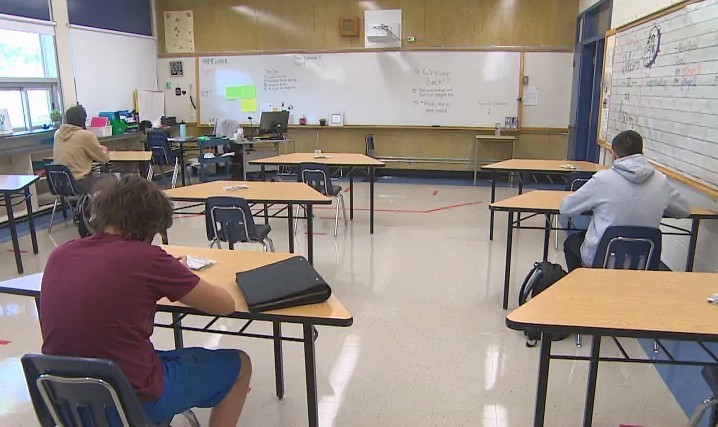

Back to school

The province wrung its hands over sending students back to school this fall before deciding classes would resume under a number of restrictions.

It ruled out the idea of remote learning, saying parents unwilling to send their children to class would need to register for home-schooling instead.

The plan faced criticism from many parents as well as teachers, who held rallies and demonstrations against it.

Students returned Sept. 8, and it didn’t take long for COVID-19 to show up. On Sept. 9, the province announced a Grade 7 student at Winnipeg's Churchill High School had tested positive, but was asymptomatic.

Health officials said the risk to others was low because the student wore a mask and maintained proper distancing.

But the spread of COVID-19 in schools was a risk many parents decided they didn't want to take. Latest figures from the province show an almost 25 per cent increase in home-schooling registrations compared to 2019.

1st case on First Nation in Manitoba

The same week that the first case showed up in a school, the first case appeared on a First Nation in Manitoba. The chief and council of Fisher River Cree Nation, north of Winnipeg, confirmed the case to CBC News on Sept. 11.

As of Sept. 11, Manitoba had recorded 182 new cases in September, bringing the total since the pandemic's start to 1,393. Of those, 1,090 people have recovered and 16 have died. There are 287 active cases, including 12 in hospital — four in intensive care.

More than 151,000 Manitobans have been tested for the illness.

Globally, as of Sept. 11, there have been 28,040,853 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 906,092 deaths, according to the WHO.

Failures and the future

The past six months have exposed several shortcomings, said the U of M's Jones, who wrote the book Influenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg.

"Obviously, long-term care is a system that now needs significant investment and repair. We need better resources for the elderly," she said.

While comparing the two pandemics is fascinating, it is concerning to see some themes repeated, such as stigmatization, income inequality and gaps in the social safety net, Jones said.

“Things like the absence of sick pay, for example, so that people are still having to make a decision between being sick and staying home just to be safe,” she said.

The exposure of those issues provides an opportunity now to make changes, said the U of W's MacKinnon.

“Has this made us realize that we want to be the kind of society where we look out for each other and we put systems in place so that people have access to the care they need — in particular looking at what's happened with the elderly?” she said.

“People have known for years that there are gaps in the system but this has really brought that to light, and there is an opportunity to correct that.”

A drastic difference in this pandemic compared to 1918 is the large-scale shutdown to curb infection rate. A century ago, the disease ran through the community until the pool of hosts was exhausted.

With the measures taken this time around, Jones said it’s likely COVID-19 will always be present.

“We need to ... think of it as being more like an endemic disease that we need to constantly be aware of. There's still a lot of unanswered questions about how we could possibly return to normal and learn to live with it,” she said.

Kindrachuk agrees.

"What we're realizing now is that this virus is extremely complex ... and it will take probably quite a few years for us to fully understand and appreciate what it can do to individuals," Kindrachuk said, referring to cardiac implications and recent theories it can affect neurons in the brain.

“Our best plan for moving ahead is to increase our preparedness and also appreciate that something as simple as a virus can completely reorganize and devastate not only health care systems, but global economies.”