UPDATE: On Oct. 2, 2018, less than a month after this article was published, LNG Canada announced it will go ahead with the $40-billion project.

In the two decades since Aaron Gallagher packed his bags and left Vancouver Island for work in Alberta, he's made the province his home and its biggest industry his career.

The oilfield services sales manager speaks proudly of both, recalling how, in good times, he could work three months straight — without a day off. When things are bad, he says, people dig deep to find enough work to feed their families.

The father of two, sporting a dark cap, its brim pulled down low, cracks a smile, recalling an expression he said he heard the other day about life in the oilpatch.

"Sometimes I eat chicken, and sometimes I eat feathers," said Gallagher, chatting from an office on the edge of Grande Prairie in northwest Alberta. "It sums up the industry in the last few years. And yes, it has been frustrating."

The Canadian oilpatch has been through some tough times recently and is now making the long climb back from the commodity price crash that started in mid-2014 and led to tens of thousands of layoffs.

There is cautious optimism that the future of the energy sector promises more chicken than feathers — and one reason is a proposed $40-billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) project on Canada's West Coast. The price tag includes a new 670-kilometre pipeline that would ship gas from northeast British Columbia to the site of the proposed facility in Kitimat.

The LNG Canada project, first announced in 2011, not only has the potential to be one of the priciest construction ventures in Canadian history but a much-needed linchpin for the country's foray into a $90-billion global market. While Canada has a single LNG import facility on the East Coast, the country doesn't have any export terminals.

With vast supplies of natural gas in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada looks ready to compete with the United States, Australia and others for a share of the growing LNG market.

While a series of other LNG projects have fallen apart in recent years, some analysts believe this project is practically a done deal — that the consortium behind LNG Canada, a group led by Royal Dutch Shell, will give it final approval in the coming weeks.

Certainly, it appears to be gathering momentum.

Malaysia's state-owned energy company, Petronas, took a 25 per cent stake in LNG Canada this spring. Contracts have been awarded to supply work camps along the proposed pipeline route on the condition the LNG terminal is built. Preparation for marine construction that would increase the depth of the berthing areas in the Port of Kitimat is starting this summer.

It's really important for our industry. It's important for pricing and for jobs and tax revenues.

Timing for the project could be critical because the next wave of LNG demand is expected to hit in the early 2020s, meaning the project's clock may already be ticking.

For Shell's part, the company told investors last month that the project looks "very promising" but indicated more homework was still needed.

"We see great opportunities but we also have clear expectations when it comes to competitiveness, affordability and returns," chief financial officer Jessica Uhl told analysts.

What is certain is Canada's energy sector has a lot riding on Shell's decision.

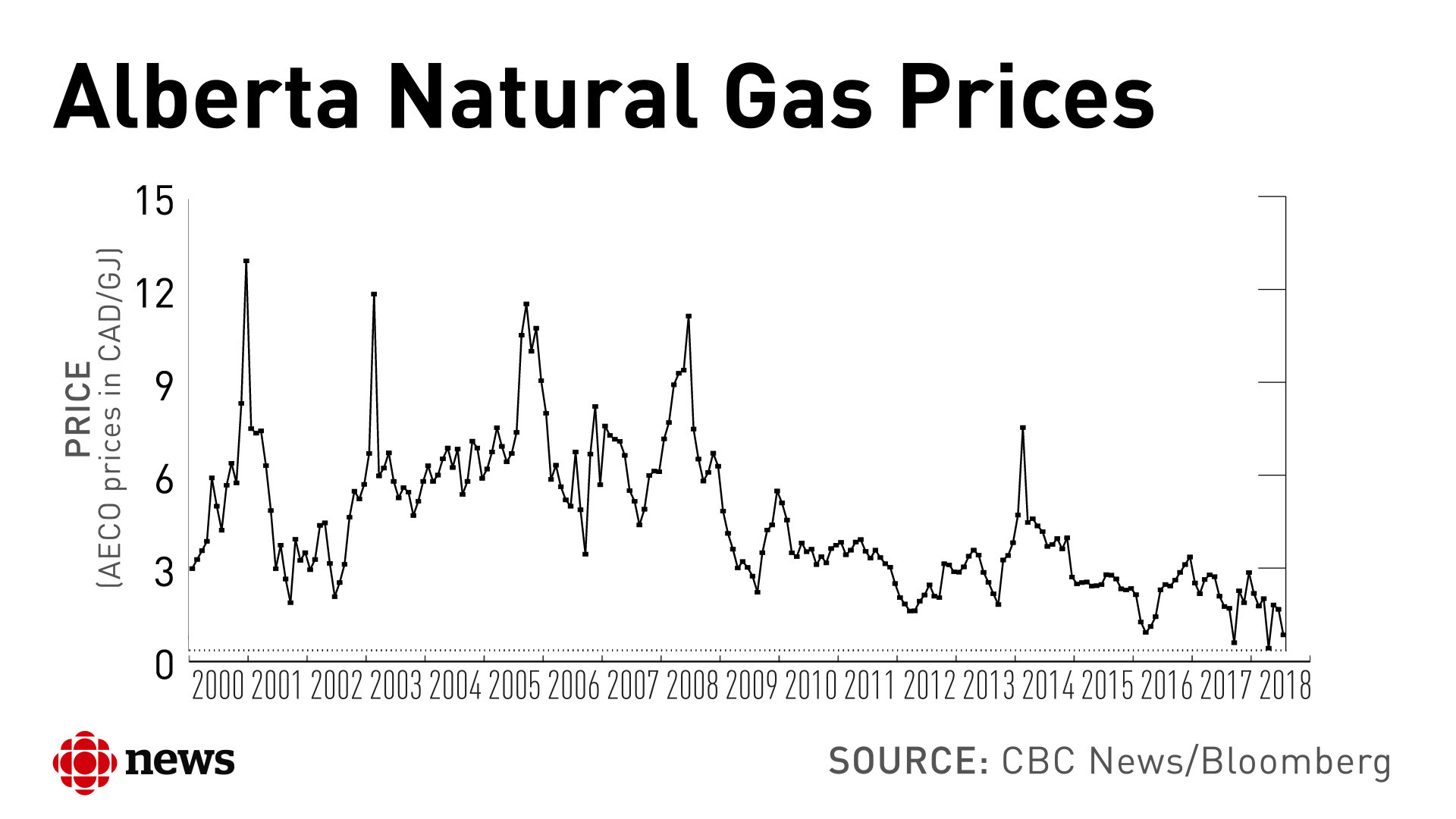

If the LNG industry fails to launch, some believe natural gas's future in Western Canada will languish, as Canada's only customer for natural gas — the U.S. — ramps up development of its own resources and weans itself off imports.

But a thumbs-up on the project could send a powerful signal to the industry that Canada wants investment and economic development — especially after recent headlines that might suggest otherwise, including Kinder Morgan backing out on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project and the federal government blocking the Chinese takeover of the construction firm AECON.

Royal Dutch Shell chief executive Ben van Beurden talks LNG prospects at CERAWeek in March 2018.

Across the Canadian energy sector, people are watching closely for developments.

"It's tremendously important for our economy," said Jonathan Wright, CEO of NuVista Energy, a Calgary-based oil and gas company with a focus on northwest Alberta.

"We must connect to the world price. It's really important for our industry. It's important for pricing and for jobs and tax revenues."

A growing market

In simple terms, LNG plants take natural gas and liquefy it so it can be put on tankers and exported. Once it arrives at its destination, it is regasified, sold and shipped in its original state.

There's a big market.

Global natural gas consumption is set to grow by 45 per cent over the next 25 years, according to the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI). Most of the growth should come from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East.

LNG is expected to be key in meeting that demand. Some estimates say it will account for half of globally traded natural gas by 2035, up from roughly one-third today.

The opportunity for Canada rests on the fact that while global gas markets are well supplied for now, there's an expected supply gap coming in the early- to mid-2020s.

"Investment in new capacity, therefore, is needed from 2020 onward," says CERI's latest report on LNG in Canada, issued in July.

Canada has the gas to help fill that gap. The Montney and Duvernay formations, which stretch across the northern boundary of Alberta and B.C., contain massive amounts of natural gas.

Montney alone has been estimated to have enough natural gas to meet Canada's needs for 145 years.

"The resource base in the Montney is so large that it really dwarfs anything that we've discovered in Western Canada before," said Hal Kvisle, a longtime oilpatch executive and former TransCanada CEO.

"There's no capacity in the North American market to demand all of the gas that the Montney can produce."

The potential of the Montney is a big reason why there's so much activity in the region, including in Grande Prairie.

It's a hub for oil and gas, a hot spot for work and the place to come for everything from groceries to RVs, whether you live in Alberta or across the border in B.C. It's not a quite a "boom," like four or five years ago, but it has some of the hallmarks, including lots of "Help Wanted" signs.

"If you look at the Grande Prairie area compared to the rest of the province, we are significantly busier," said Rob Petrone, longtime president of the local petroleum association.

"All of it is driven by this development of the Montney and the expectations down the road to get our product to markets."

U.S. market drying up

LNG could open up new markets and drive further development. Some experts say it's vital.

Historically, natural gas exports from Western Canada have gone to the U.S. But that market will shrink as the U.S. focuses on its own abundant resources.

Canada must either prepare itself for a decline in natural gas production — and the associated economic benefits — or consider growth through LNG exports, the CERI report says.

"The benefits that [an LNG industry] would provide to the natural gas sector is diversity of demand," CERI president Allan Fogwill said. "And right now we are suffering a little bit on that, because a significant portion of our demand is going to the U.S. export market and we are losing that market over time."

Analyst Samir Kayande, with the Calgary-based RS Energy Group, doesn't think a single LNG project alone will significantly boost natural gas prices for the entire industry. There's simply too much supply of natural gas.

"If you increase demand by a little bit, it helps, but not by much," he said.

"You need to have transportation and demand options that are always increasing over time. So it may not be the first LNG plant. Maybe you need another one, and another one after that."

If LNG Canada proceeds, the hope in the industry is it will spur other projects to take off. In other countries, the LNG sector has tended to cluster together.

Multiple facilities would ultimately mean more drilling, royalties and tax revenue. In northwest Alberta and northeast B.C., it should also mean more work.

"Just having that additional demand will create more jobs," said Brian Glavin, Grande Prairie's head of economic development.

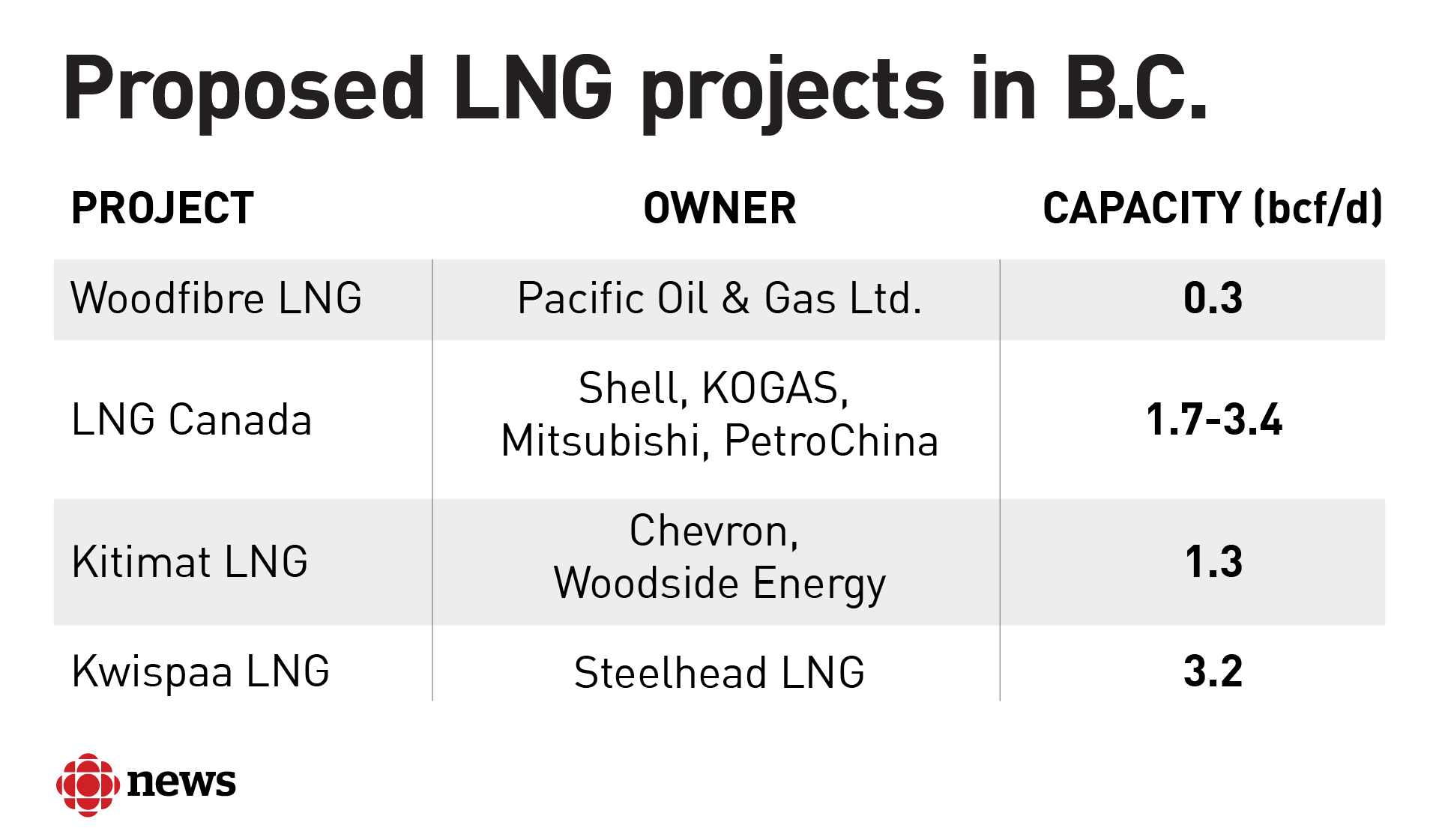

There are currently four active LNG project proposals for B.C.

"This LNG has the potential to be similar to oilsands in terms of its economic contribution, because these projects are very big and there's real potential to see more growth than just one project," said Jackie Forrest, senior director at the ARC Energy Research Institute in Calgary.

LNG Canada alone could create 10,000 construction jobs and up to 950 full-time jobs, according to the B.C. government, and generate $22 billion in direct government revenue over 40 years.

Does it make sense?

Despite all of the potential upside for the region, companies like Shell are still deciding whether setting up shop in Canada will pay off.

During its recent second-quarter update, Shell spoke of LNG Canada's promise, including abundant and low-cost gas as well as short shipping distances to North Asia.

"We have an attractive portfolio of new supply options ... [and] want to select the most competitive source of supply. LNG Canada is the most mature of these options," said Uhl, Shell's CFO.

But the LNG industry still faces hurdles in Canada.

A number of countries with substantial reserves of natural gas already have LNG facilities, including the U.S. and global leader Qatar. Canada's lack of experience puts it at a disadvantage.

Canadian projects will need to be cost-competitive with international options, the CERI report says. The country also needs to look stable and predictable as the federal government proceeds with substantial changes to the regulatory process.

Fogwill, the think-tank's president, remains convinced Canada can compete.

"There is a very reasonable opportunity … to demonstrate that Western Canadian LNG can be cost-competitive in Japan and, as a result, the Asian market generally," he said.

Construction of the LNG project would provide a large financial boost for Kitimat, B.C., and other communities along the pipeline route, UBC professor Werner Antweiler says.

More than a dozen proposed projects for the West Coast have previously been shelved or discontinued in the last decade, so there is reason to be skeptical of the hype surrounding LNG in Canada.

Shell is developing LNG proposals in different parts of the world, and the company may decide one of those projects makes better financial sense.

"We really have to see how the particular project fits into the investment cycle of Shell and its partners, because they are looking at multiple projects," said Werner Antweiler, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business.

"Whether this project goes ahead really depends on how far [Shell is] ahead with these other projects in comparison to the LNG Canada project in Kitimat, and if the capital situation actually will allow it to move ahead with this at this point."

Antweiler points to Shell's proposed Lake Charles LNG facility in Louisiana as an example of a viable project that could leapfrog a Canadian investment; it is ready to be built, but Shell has so far delayed construction.

Any Canadian LNG project will also need some assurance on getting a good price for its gas.

Global LNG prices have fallen in recent years but are expected to rise in the next few years. Prices are hovering above $8 US per million British thermal units. A recent report by energy consultants Wood Mackenzie said LNG Canada would need prices of around $9 to break even, although other analysts think prices may need to be even higher.

"I think they need to be more like $11 or $12 for this project really to be financially viable," Antweiler said.

"So if an investment decision is made this fall, it would be on the basis of projections."

The cost of construction could also be a factor, as it's typically more expensive to build large energy projects in Canada — and Kitimat's remote location, about 1,000 kilometres up the coast from Vancouver, doesn't help.

"Canada is a painfully expensive place to do business, partly because of ponderous regulatory regime," said oilpatch veteran Kvisle. "But also you've got to remember Kitimat is not exactly a global energy hub."

Tariffs, politics and the environment

LNG Canada has also yet to resolve a dispute with the federal government over steel tariffs that could reportedly add at least $1 billion to the project's cost.

The Shell-led group wants to use certain supplies from China because it says it cannot afford to wait years to see whether Canadian manufacturers can construct the large LNG modules it needs. That's why the group argues it shouldn't pay tariffs on importing those steel supplies.

But industry stakeholders such as the Canadian Institute of Steel Construction want Ottawa to maintain the border duties.

LNG Canada hasn't run into the same political or environmental headwinds as the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, but there are some high-profile opponents to developing the industry in Western Canada.

The David Suzuki Foundation has voiced concern about the impact of natural gas development in northeastern B.C., while the Sierra Club warns that B.C. "can't build LNG plants and meet emissions targets."

Project backers say natural gas is clean compared to other fossil fuels such as petroleum and coal, and that the proposed facility is designed to be the lowest carbon-emitting plant of its kind.

Safety concerns about developing the industry on the West Coast have also been raised over the years. Natural gas is combustible and flammable so the consequences of an industrial accident can be dire. According to proponents, though, LNG's track record when it comes to safety is enviable.

The environmental consequences of a hull breach, they say, are also less serious for LNG, which is non-toxic and can dissipate into the air, unlike a spill from an oil tanker.

A massive LNG project would boost natural gas prices, but only temporarily, according to RS Energy Group analyst Samir Kayande.

Politically, B.C. Premier John Horgan, a Trans Mountain opponent, is a backer of the LNG Canada project — even though his NDP government's minority partner, the Green Party, is opposed.

And while Indigenous communities appear divided on construction of Trans Mountain, there seems to be broader support for LNG.

A recent report commissioned by the B.C. government found many Indigenous groups are disappointed that no LNG projects have been built, as they want to capitalize on the economic development.

‘Already missed one opportunity’

Shell is expected to make its decision in the coming months — and that decision could have an impact that lasts decades.

It could be the difference between an expanding or languishing natural gas sector in Western Canada — an outcome that will have repercussions for the environment, jobs and government spending.

For those working in the oilpatch, they hope there's more chicken than feathers around the corner.

"Here it is, just about 2019 already, [and] the next wave for LNG worldwide is 2022," said Petrone, with the local petroleum association in Grande Prairie. "We've already missed one opportunity. We can't miss another one."