December 9, 2018

Mike Freides is afraid of laundromats. Which is odd, perhaps, for someone who owns one.

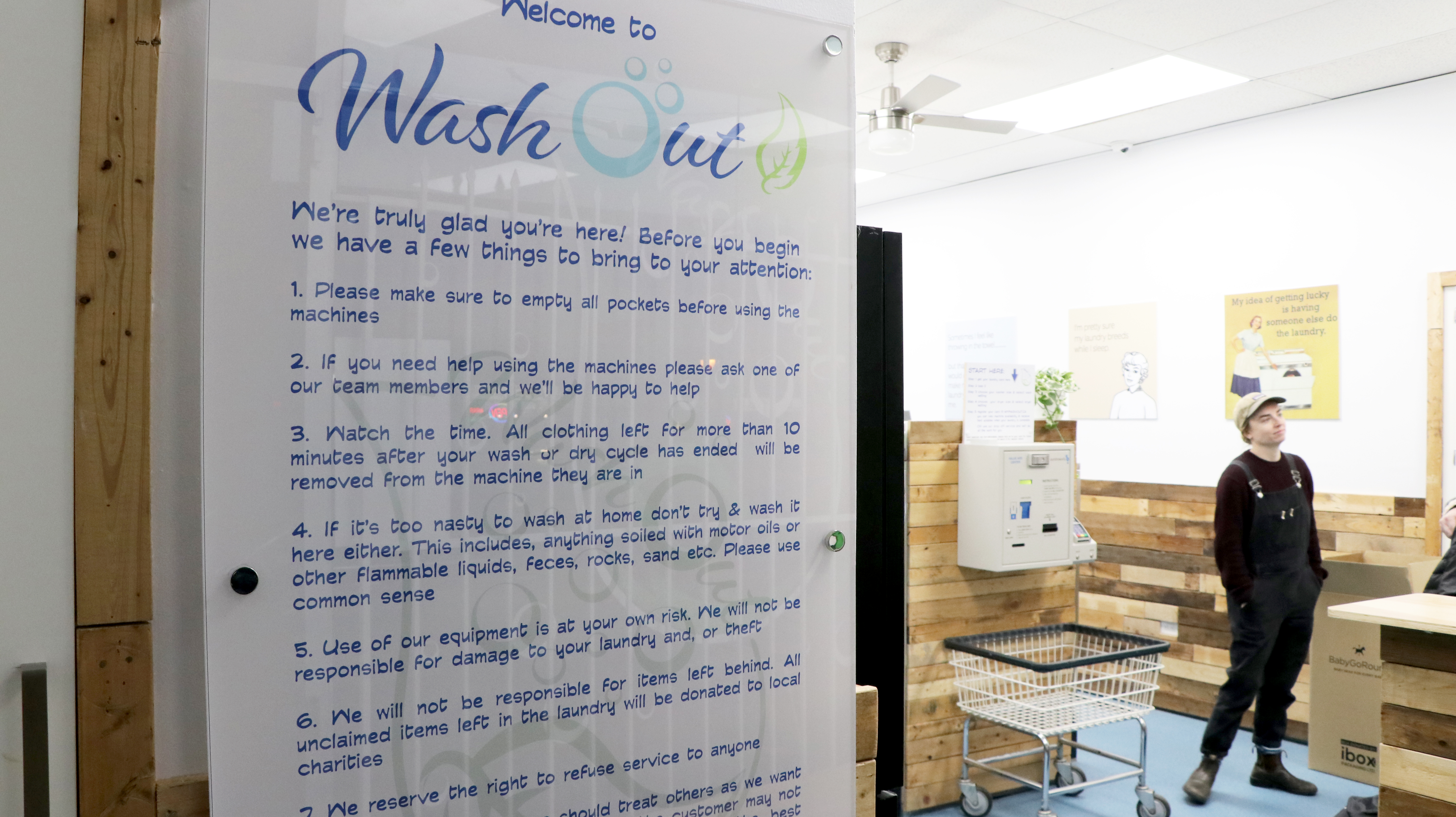

“Most laundromats you go to are really scary, especially in this city,” Freides said, standing under the glare of the bright neon lights of his Vancouver shop WashOut laundromat.

Many of the city's coin-operated laundromats have seen better days. Worn vinyl floors, bare walls and broken pastel-coloured furniture are their typical features.

But Freides is not running your typical urban laundromat.

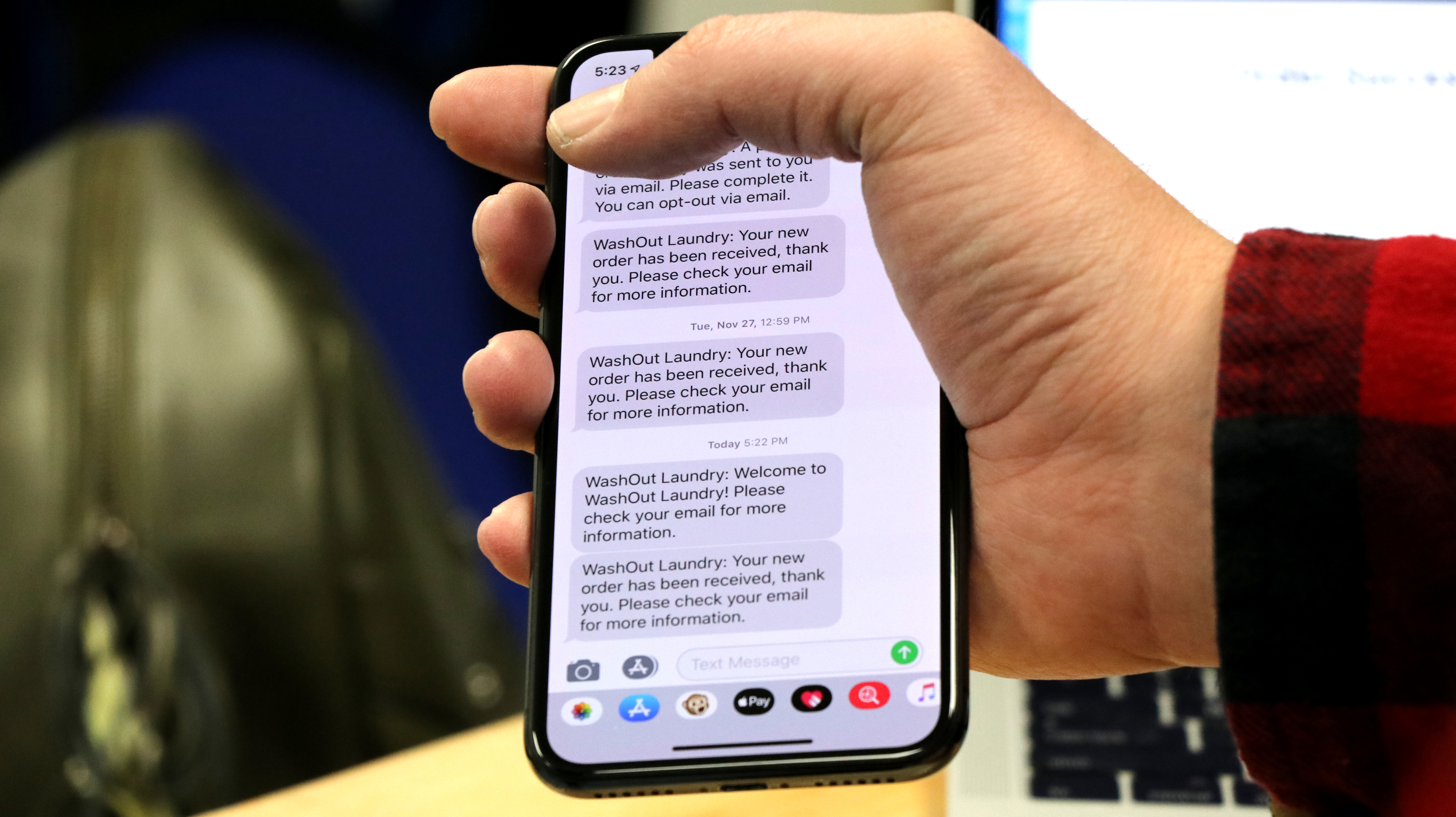

Around him are rows of stainless steel, high-efficiency washers and dryers designed to text users when their cycle is done. The small space is pristine. A bored staffer in overalls sits behind a wood-panelled desk that holds little more than an iPad.

Freides, 37, used to work in online marketing and has never owned a retail space. But he says he has invested $750,000, most of it his own money, on this laundromat, which opened last September in the heart of the city’s Commercial Drive neighbourhood.

It’s a gamble he’s confident will pay off.

He’s betting customers will be willing to pay about $30 per load for someone to pick up their laundry from their home, wash, dry and fold it, and deliver it back to them 24 hours later ― with all of it ordered from the convenience of an app.

“The service is really the main focus of the business,” Freides said. “I want to be the SkipTheDishes of laundry.”

His isn't the first laundromat to offer those services in Vancouver, but it's one of just a few. And businesses like his are popping up in major cities across Canada.

Freides grew up in Burnaby and around B.C. As an adult he lived in L.A., New Jersey and Las Vegas, where he often used laundry delivery. But when he moved back to Vancouver a couple of years ago, he didn’t see anyone offering the service. He saw the gap as an opportunity.

Watch Freides give a tour of his high tech laundromat.

Mike Freides says his high-tech, eco-friendly machines and card-based payment system set his laundromat apart from the pack.

It’s a risky proposition. In some cities, traditional laundromats are dying. In Vancouver, 10 years ago, 77 businesses were classified as coin-operated laundromats. Today, there are only 47.

But like much of the service industry, the sector is changing.

Sunil Johal, policy director of the University of Toronto’s Mowat Centre, says app-based businesses that outsource daily chores are a trend across the service industry.

“The notion of waiting in line or waiting to do your laundry when you could just push a button and have somebody come pick it up and drop it off for you really fits in with the kind of more time-pressed, on-the-go world that we live in today,” Johal said.

“[People] like the convenience of it, even though it might be more costly.”

For Freides, an app-based laundromat makes good business sense. It’s also an opportunity to merge his experience working in online marketing with his desire to run a brick-and-mortar enterprise.

“In my previous jobs that I've had, I stared at computer screens all day,” he said. “I get to physically do something there. There's something tangible.”

For decades, laundromat owners were often entrepreneurs ― many of them new immigrants ― with a penchant for fixing appliances, according to the U.S.-based Coin Laundry Association.

Brian Wallace, the association’s president, says laundromats have long thrived in low-income, densely populated neighbourhoods with lots of renters.

“The more people, the more dirty clothes,” Wallace said over the phone from his office in Chicago.

But some industry experts say conventional laundromats are dying out. New apartments and condos increasingly offer in-suite laundry. And rising costs like utilities and commercial real estate rents have eaten into profit margins.

Laundromat owners have had to innovate to survive.

One older owner in Vancouver, who preferred not to be named because he is trying to sell his business, referred to the self-service portion of his laundromat as “a kind of charity” because it now earns him so little income. To sustain himself, he also repairs boots and vacuums.

Other owners are finding ways to reach new customers. Wallace says many owners are attracting higher-income customers with more expensive “wash and fold” services. And some are also entering the digital arena to include online and app-based services to match.

Owners now need to know as much about how to get a top ranking on a Google search as they do about fixing a dryer.

“One might not think that sort of what is perceived to be an old-school, mechanical analogue industry like laundromats would be disrupted by technology,” Wallace said.

“Digital marketing is affecting just about every business around, including the neighbourhood laundromat.”

New laundry operator Freides believes that trend will work in his favour.

As of last week, his customers can place an order online to have someone wash, dry, fold and iron their clothes via the laundromat’s new app. The service includes home delivery.

Not only is he banking on making a return on his $750,000 investment, he wants to open new locations in Vancouver and Toronto.

“We're just a society of convenience now,” he said.

“You have better things to do with your time than to be doing your laundry.”