July 21, 2019

On a sunny afternoon, a busker plays a few hits on Cumberland, B.C.'s historic and hip main drag.

Mountain bikers roll up and down bike lanes alongside cars and trucks that also have racks full of bikes.

Those who are not on bikes window shop or head to the brew pub, taco shop or one of several trendy new cafés in this village of about 4,000 people located in the heart of the Comox Valley, on the eastern side of Vancouver Island.

The new Cumberland has a decidedly lighter environmental footprint than its historic past as a coal mining and logging town. It has transformed into a youthful, vibrant village defined by a shared love of conserving the forest that surrounds it.

The roots of this impressive revival are found in seemingly endless hectares of mature coastal Douglas fir trees that hug the edge of the few dense blocks that make up the heart of the village.

A grassroots movement to conserve the forest started gaining momentum nearly 20 years ago when a swath of land particularly close to town was logged.

The Cumerbland Forest Society formed with the goal of saving what remained for the use and enjoyment of the community and conserving key salmon bearing creeks, wetlands and riparian areas.

It was a unique situation. The forest lands around Cumberland are privately owned, rather than Crown land, thanks to a land transfer back in the 1800s that made way for a rail line to be built across Vancouver Island.

Instead of having to sway government officials, the society could just purchase the land. But it wouldn't come cheap.

"They thought the community was nuts," says Meaghan Cursons, executive director of the Cumberland Community Forest Society.

"Like how are you gonna do this? We call that the David and Goliath story. How are you going to do this on bake sales and plant sales?"

Despite the odds, the plan worked.

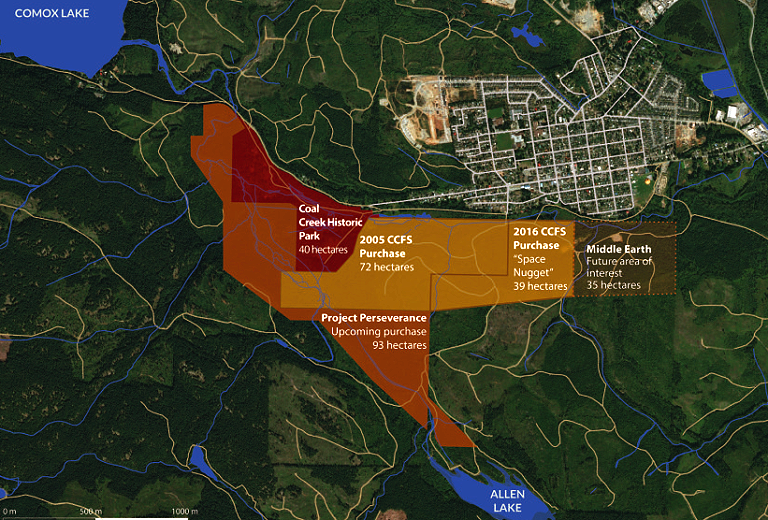

The society raised more than a million dollars to buy the first plot of forest. In total, 110 hectares of forest, which is also in the traditional territory of the K’omoks Nation, have now been conserved, with a campaign underway again to buy more.

Another group in Cumberland also saw potential amongst the trees. Local mountain bikers had long built trails through forestry lands.

But the trails were essentially illegal and had no protection from logging activity.

The United Riders of Cumberland formed to help advocate for a better way to share the land, says Jeremy Grasby, who moved to the village in the early 2000s and opened the Riding Fool Hostel.

"We signed a land use agreement which was pretty monumental for Vancouver Island," he says. "We provided public access on private land."

That land use agreement which includes private landowners, logging companies and the Village of Cumberland, gave local mountain bikers the ability to expand the trail network and install key infrastructure such as bridges over creeks.

The trail network has flourished in the years since. It now twists and turns through nearly 200 kilometres of forest in both the conserved areas and on forestry lands.

"I don't think there was any grand vision of let's create this destination. It was trail by trail, like just mountain bikers wanting to build trail and maybe just carve some for ourselves."

But word is certainly out in the mountain bike community. Two-wheel enthusiasts flock to the village in droves to ride what has become known as a legendary trail network. So much so, mountain biking is now a key piece of Cumberland's economy.

"It's paramount right. If you look at the businesses up and down main street, they all have vehicles there with mountain bikes on the rack," Grasby says.

"People are coming as a destination mountain bike community."

For Mayor Leslie Baird, the transformation of the local economy based on lifestyle and tourism has been remarkable.

Baird was born and raised in the village and her father worked in the mines.

"In the 1960s, it was finished. No one wanted coal anymore. The logging still continued on but the companies were changing. You used to work for one company and you would retire with that company and that doesn't happen anymore."

Standing in front of Cumberland's museum, which reminds newcomers of the rich labour history of the area, along with the story of the Japanese and Chinese communities that settled in the village to work in the mines and nearby mills, Baird sees a transformed main street.

While there are still a few empty storefronts, restaurants and small businesses that specialize in handmade, local and vintage products have largely filled the storefronts of the historic buildings that line a few blocks in the core of the village.

"We've been found by many people and they move here for the the lifestyle. You can walk out your door and go get on the trails," Baird says.

"The average age in Cumberland is 38. And so, it is an anomaly in B.C.

There are growing pains as the village dynamics change. Housing prices have skyrocketed, making it tough for some people who grew up here to stay.

There is also a worry some of the artists that contribute to the thriving culture of the village are being pushed out by the high cost of living.

And then, there is the onslaught of mountain bikers, which hasn't sat well with everyone.

"There's people that do not Like it. It can be a challenge sometimes to try and make it workable for everyone," Baird says.

As the village changes and traffic increases on the trail network, those who helped Cumberland find its natural identity are starting new conversations about the relationship with the forest.

"Our challenge is going to be, yeah, how do we have these deeply embedded with nature relationships that don't mess up the places we're trying to protect," says Cursons from the Cumberland Community Forest Society.

That likely means working to conserve Cumberland's wild nature, not just from industry but from its own growing popularity.

"There's some of us who are still focusing on keep it wild, keep it weird."

This story is part of the CBC series Footprint examining climate change issues and solutions in communities across Canada. For more stories visit: cbc.ca/Footprint.