November 18, 2021

There is a grime-coated bridge in The Pas, Man., that connects the small community to the neighbouring First Nation, and on this cold autumn day, the blood red ribbons attached to the rails whip wildly in the wind.

But it's the faded black grafitti at the side of the bridge that catches the eye if one looks a little closer.

"Stop killing us."

The worn red ribbons on the Cornelius Bignell Bridge, en route to the Opaskwayak Cree Nation, are a makeshift testament to the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in the province.

"My big thought is: Why are they taking us? They’re still taking us," says Rita McIvor, who is from Tataskweyak Cree Nation, about 900 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, but grew up in The Pas.

"It's scary. If you’re alone, anything can happen."

The grim graffiti message is also a sign of the times.

Fifty years after Cree teenager Helen Betty Osborne was pulled off the streets of The Pas, beaten and fatally stabbed, and 30 years after the province’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry investigated the racism that fuelled both her death and the flawed police investigation afterwards, Indigenous women, men and children are still the targets of racism-fuelled violence.

"How much anger is done to a human being to be stabbed 57 times?" says McIvor, who was a friend and classmate of Osborne. "There’s still racism here and it’s alive and well."

In April 1988, the province launched the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in response to the 1971 murder of Osborne and the 1988 police shooting of Oji-Cree leader John Joseph Harper in Winnipeg.

The inquiry’s mandate was clear: "To consider whether and the extent to which Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal persons are treated differently by the justice system and whether there are specific adverse effects, including possible systemic discrimination against Aboriginal people, in the justice system," the report reads.

Over 123 days, co-commissioners Associate Chief Judge Murray Sinclair and Associate Chief Justice Alvin Hamilton travelled more than 18,000 kilometres throughout the province, hearing stories and receiving more than 1,200 presentations and exhibits.

“After 30 years, somebody is not listening. Somebody is not doing anything to change the status quo.”

In November 1991, relying on approximately 21,000 pages of transcripts, they released a two-volume report. Their findings were stark.

"In almost every aspect of our legal system, the treatment of Aboriginal people is tragic.… Canada's treatment of its first citizens has been an international disgrace," Hamilton and Sinclair concluded.

The report outlined 296 recommendations intended to right the racism-fuelled wrongs of Manitoba’s justice system.

Yet three decades later, the majority of the recommendations have not been implemented. Indigenous men and women continue to be targeted and assaulted, overrepresented in jails and underrepresented in the judiciary process.

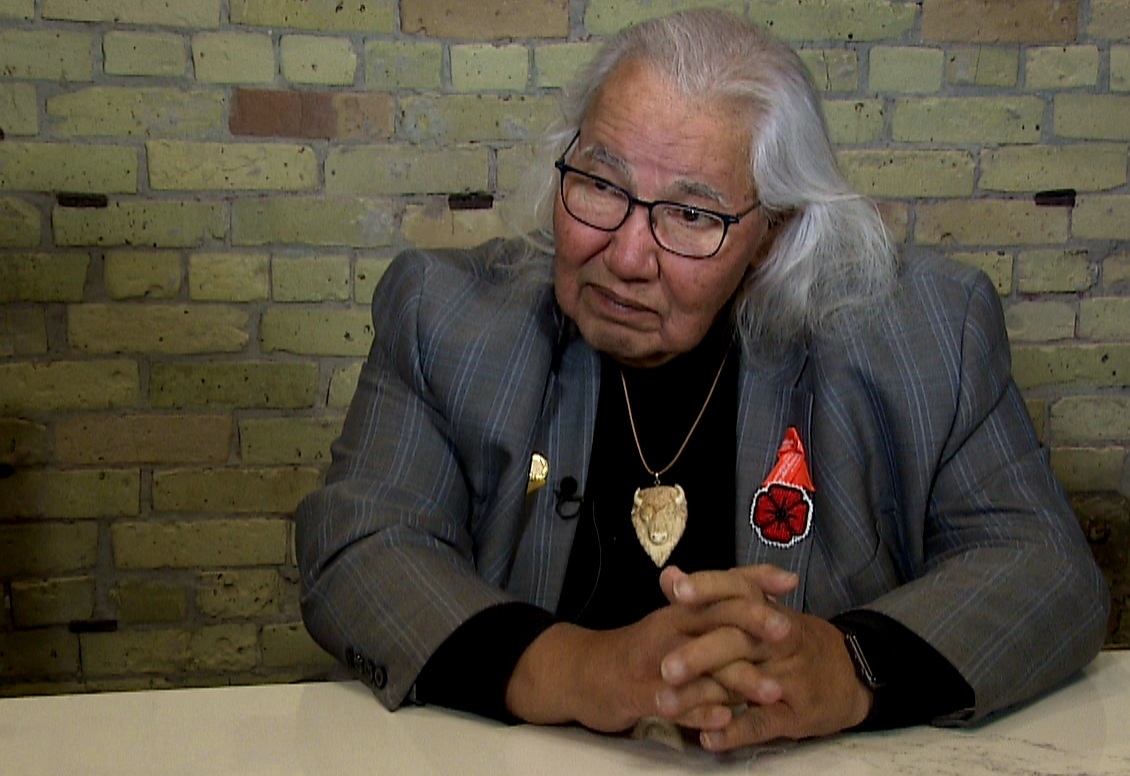

"After 30 years, somebody is not listening," says Garrison Settee, Grand Chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, which represents 26 First Nations in northern Manitoba. "Somebody is not doing anything to change the status quo."

Crime and coverup

In the winter months after Osborne was murdered outside The Pas in 1971, locals would toast one of the suspects with a special drink whenever he entered the bar, Murray Sinclair says he was told.

It was a stunning revelation during the inquiry that so disturbed Sinclair images of the Ku Klux Klan came to mind, he says.

"You almost kind of expected to start hearing stories about hooded people driving around, hunting down Indigenous guys and Indigenous families," Sinclair says. "That was a new [level] of awareness for me, no question."

The inquiry investigation further revealed that while some RCMP did due diligence in their pursuit of the alleged killers, "the major factor was that those who knew what had happened did not or would not speak to the police," the report concludes.

For close to 15 years, the inquiry revealed, community members — including a court sheriff — knew the names of the suspects allegedly behind the killing but let the suspects and their secrets hide in plain sight.

"I wasn't aware that they and an entire community of non-Indigenous people would hold such a secret for so long," Sinclair says.

What's worse, Sinclair says, was that Osborne’s case was not an anomaly.

"I knew about white boys picking up Indigenous girls and sexually assaulting them, throwing them out of the car in dark places."

In the end, one man — Dwayne Archie Johnston — was convicted of second-degree murder almost 17 years after the crime.

The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry's probe into Osborne’s death generated a broad list of recommendations to protect Indigenous women and children from violence — both from strangers off the streets and partners in the home — including calls for:

- The creation of police, social worker and abuse teams to deal with women involved in domestic violence.

- More Indigenous-led safe houses and supports for vulnerable women.

Some recommendations specifically targeted racism in policing, such as:

- More community-based policing in predominantly Indigenous populations, cross-cultural training among police officers and justice officials.

- Further training, disciplinary action or dismissal among those already in law enforcement who display racist behaviour.

- Better screening of recruits who want to get into law enforcement. Any candidate displaying racist attitudes should be screened out of training. Police officers should be rotated through cross-cultural education programs.

“Every time there is anyone missing, the first thought is: ‘I wonder if they’re murdered’ "

Both the Winnipeg Police Service and the RCMP now have versions of cultural training programs for their recruits.

In April 2021, the province committed $6.4 million to community organizations, which include Indigenous-led agencies to "address violence against Indigenous women, girls and Indigenous-led agencies developing projects to address violence against Indigenous 2SLGBTQQIA+ people," Manitoba Justice Minister Cameron Friesen said this month in a written statement to CBC Manitoba.

But most of these efforts are too little and too late, critics say.

Currently, according to the Native Women's Association of Canada, it's estimated that close to 1,200 Indigenous women and girls are missing or have been murdered across Canada. In Manitoba alone, hundreds have gone missing through the years.

What's more, according to the NWAC, investigations into the homicides of Indigenous victims are solved far less often than investigations into the homicides of non-Indigenous victims.

Which means Rita McIvor can never really feel safe.

"Every time there is anyone missing, the first thought is: 'I wonder if they're murdered,' " McIvor says. "Always wondering, saying prayers that they will be found."

To serve and protect

Manitoba First Nations Police Const. Gordie Ross is a present day example of what the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry hoped to achieve — Indigenous people taking ownership of Indigenous justice, and, ideally, preventing more police-involved deaths in the process.

"First Nations police and First Nations policing, right?" says Ross, from the MFNP service offices in Opaskwayak Cree Nation. "Because I care for my people."

Others say it's that personal connection that prevents police from reaching for their gun.

"When you look at Indigenous police services across Canada, you will never hear of fatal shootings," says Settee. "Indigenous people in the system understand the culture and they know how to respond to situations, instead of reacting in a way that is detrimental to the person."

The Manitoba First Nations Police Service is a long-awaited but direct response to some of the 50-plus AJI recommendations that speak to policing in Manitoba — ones that specifically called for more Indigenous-led police forces.

The service is modelled after AJI recommendations and borne out of the Dakota Ojibway Police Service, which was created in 1977, prior to the 1991 AJI report. It changed its name to the Manitoba First Nations Police Service in 2018 and broadened its scope to include seven First Nations communities in Manitoba.

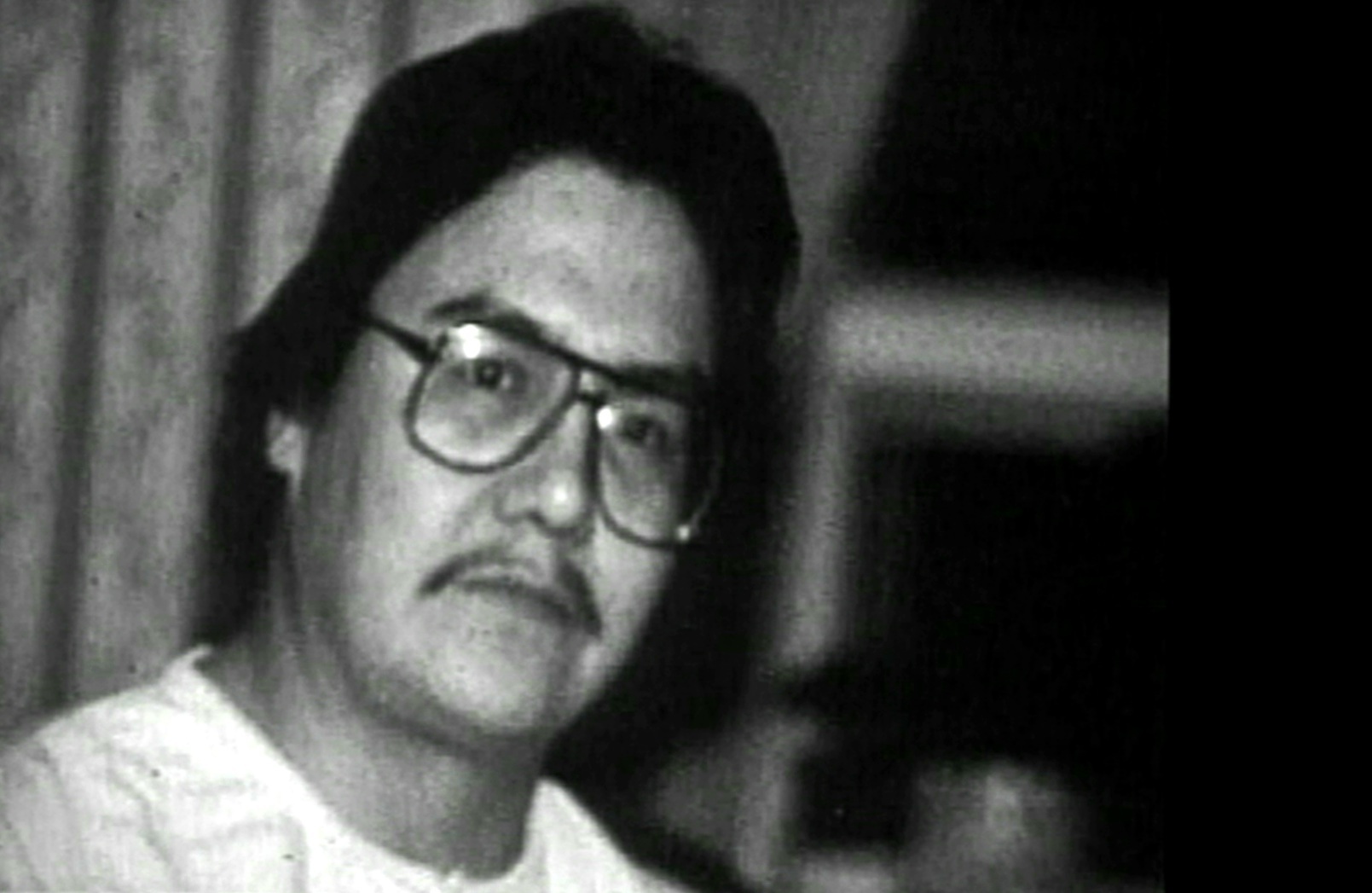

The recommendations themselves were borne out of the AJI's probe of the March 1988 police shooting of John Joseph Harper.

Harper, the executive director of the Island Lake Tribal Council, was fatally shot after an early morning encounter with a Winnipeg police officer.

Harper was unarmed. He'd committed no crime to warrant police attention.

But he happened to be Indigenous, he happened to be alone and he happened to be a short distance from an unrelated police search for an unrelated suspect who'd just been picked up by police.

Yet 24 hours after fatally shooting Harper, Winnipeg Police Const. Robert Cross was cleared of wrongdoing. Harper, the official story went, had struggled for Cross's gun, it accidentally discharged and Harper paid the lethal price for it.

The resulting inquiry revealed the lengths that police went to reconstructing the events of that night. Details emerged of altered police notebooks, potential witnesses who weren't interviewed and potential evidence that was left at the crime scene.

I drive them home or even give them a warm place to stay here in the cells, when no one will take care of them"

In the end, some AJI recommendations pertained to evidence gathering, including:

- Video or audio recording all statements taken by police.

- Video recording statements by all suspects in cases involving death and other serious crimes.

Some recommendations pertained to police-involved "incidents," including:

- Creation of a special investigations unit or a special investigations team involving independent counsel to investigate those cases.

- The existing law enforcement review board be revamped and, if the complaint involved an Indigenous victim, at least one member of the board be Indigenous.

Some recommendations have been implemented. Most, however, have not.

Since 2000, at least 89 Indigenous people across Canada have been killed in encounters with police, CBC research and investigation shows — 17 of them in Manitoba.

Statistically, it paints an ugly picture. According to the CBC Deadly Force database, which examines cases of people killed in encounters with police in Canada, Indigenous people form 16 per cent of the deaths but only 4.21 per cent of the population (annualized over 20 years).

Ross wants to change that trajectory, one police encounter at a time.

"There's a lot of substance abuse, drug abuse and I don't judge them for that," Ross says. "I talk to them, I try and encourage them when I drive them home or even give them a warm place to stay here in the cells, when no one will take care of them, right?"

In poverty and pain

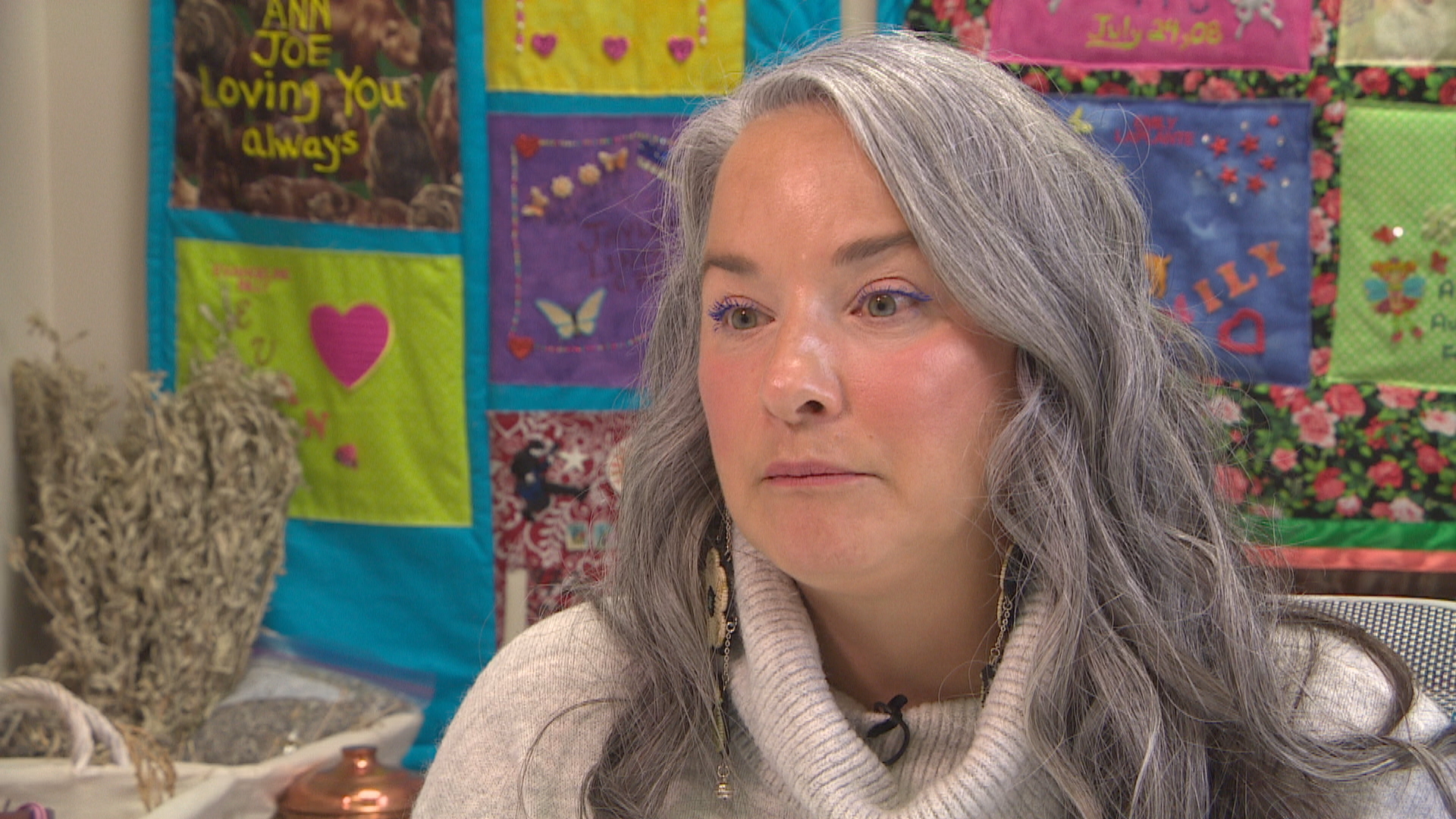

There are certain moments in one’s childhood that stay with you forever, says Nahanni Fontaine.

"One of them that I remember is when the police came for my mom," Fontaine says quietly. "I remember that."

Fast forward four decades. Fontaine, now an advocate for Indigenous women and girls, got a phone call from a young girl and her younger brother.

"She said: ‘Our mom has been arrested and we don't know what's going on. They beat her up as they were arresting her,' " Fontaine says.

"And so when I was sitting with these children, I was like: 'Oh, this is a moment these children are never going to forget in their lives.' "

Fontaine knew what question to ask next.

"I said: 'Have you guys eaten?' And they said: 'No, we haven't eaten.' "

It’s a grim scenario, but not an isolated one. According to the Office of the Correctional Investigator in 2020, 42 per cent of women in federal custody were Indigenous.

"When you talk to women and why they're there, it is always because of trauma. Addictions, dealing with that trauma and poverty," Fontaine says. "Always. One hundred per cent."

The Aboriginal Justice Inquiry listed a series of recommendations to better support Indigenous women deemed vulnerable, which it said can be sourced to the root, underlying problem: systemic racism.

The recommendations called for alternatives to incarceration appropriate to Indigenous cultures, such as group homes where women can serve their sentence while accessing programs like addictions, trauma and parenting courses.

“No matter where you go as an Indigenous woman, you're screwed."

In 2019, the Eagle Women's Lodge opened in Manitoba. But the healing lodge is the only one of its kind in the province, and one of just two across Canada specifically designed for Indigenous women.

Meanwhile in 2020, the province established the Walking Bear Therapeutic Community trauma and addictions recovery unit at the Women's Correctional Centre outside Winnipeg, where women can access treatment while incarcerated.

In 2020, the federal government committed $44.8 million over five years to build 12 new shelters to help protect Indigenous women and girls trapped in a cycle of violence. That included two in Manitoba, in the communities of Keeseekoowenin and Hollow Water.

They are good starts, Fontaine says, but not enough.

"No matter where you go as an Indigenous woman, you're screwed," Fontaine says. "And the system puts up obstacle after obstacle after obstacle after obstacle, just to survive."

The path forward

When an Indigenous person testifies in a Manitoba court today, he or she can swear their oath on an eagle feather.

Meanwhile, a council of elders has now been created to meet and guide Manitoba Justice officials in their "reconciliation" efforts with Indigenous communities.

Neither effort speaks to a specific recommendation borne out of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. Most hail from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's 94 Calls to Action, but both efforts speak to the spirit of it.

"The introduction of the eagle feather in the court systems in Manitoba is a significant step," says Settee. "And allowing for elders to be part of the sharing circles and in Indigenous justice circles.

"But I think it's only the beginning."

The province, meanwhile, in a written statement to CBC Manitoba, also noted a June 2021 announcement of the transition of the Indigenous Court Workers Program to Indigenous rights holder organizations in key regional and circuit court locations.

The province, the statement reads, “will support the transition of the program by providing annual grants totalling more than $1 million a year for two years to four rights holder organizations, including Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, Manitoba Metis Federation, the Southern Chiefs’ Organization and the Island Lake Tribal Council.”

Not all of the AJI recommendations that remain to be implemented fall under provincial jurisdiction, although most require at least some provincial support.

"They're trying to do the same thing and to expect a different result."

Recommendations regarding treaty rights, for example, could require Crown input. But in some cases, critics say, the province itself is driving the wedge (for example, the Manitoba Métis Federation’s current lawsuit over hunting rights).

The overall result is on this 30th anniversary of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry report, only a few dozen of the 296 recommendations have been implemented.

The results, where they matter most, are clear, critics say.

Since the AJI report was released in 1991, more Indigenous people are being incarcerated, compared to the rest of the population. More Indigenous persons have died in police-involved shootings. More Indigenous women and girls are being murdered or have gone missing.

"It's getting worse because they're trying to do the same thing and to expect a different result," Settee says.

"As a famous person once said: 'It's insanity to try to do the same thing over and over again and expect a different result.' And I think that applies to our justice system here in Canada."

Decades after the murder of a Cree teenager, Manitoba's Aboriginal Justice Inquiry provided a blueprint for change. But 30 years later, critics say racial injustice remains.