June 23, 2019

How a powerful new exhibit in St. John’s is going to start arguments

It starts with Joey Smallwood’s chair.

No ordinary chair, as you might imagine. It’s hand-crafted, and upholstered in seal leather. The very place where the man himself used to park his rear end for cabinet meetings.

This summer, Joey’s chair greets visitors to Future Possible: Newfoundland and Labrador Art from 1949 to the Present, a powerful exhibit at The Rooms in St. John’s.

“I wanted the seat of power to greet you as soon as you enter,” said curator Mireille Eagan, who conceived and assembled the exhibit.

The seat of power does not go unchallenged.

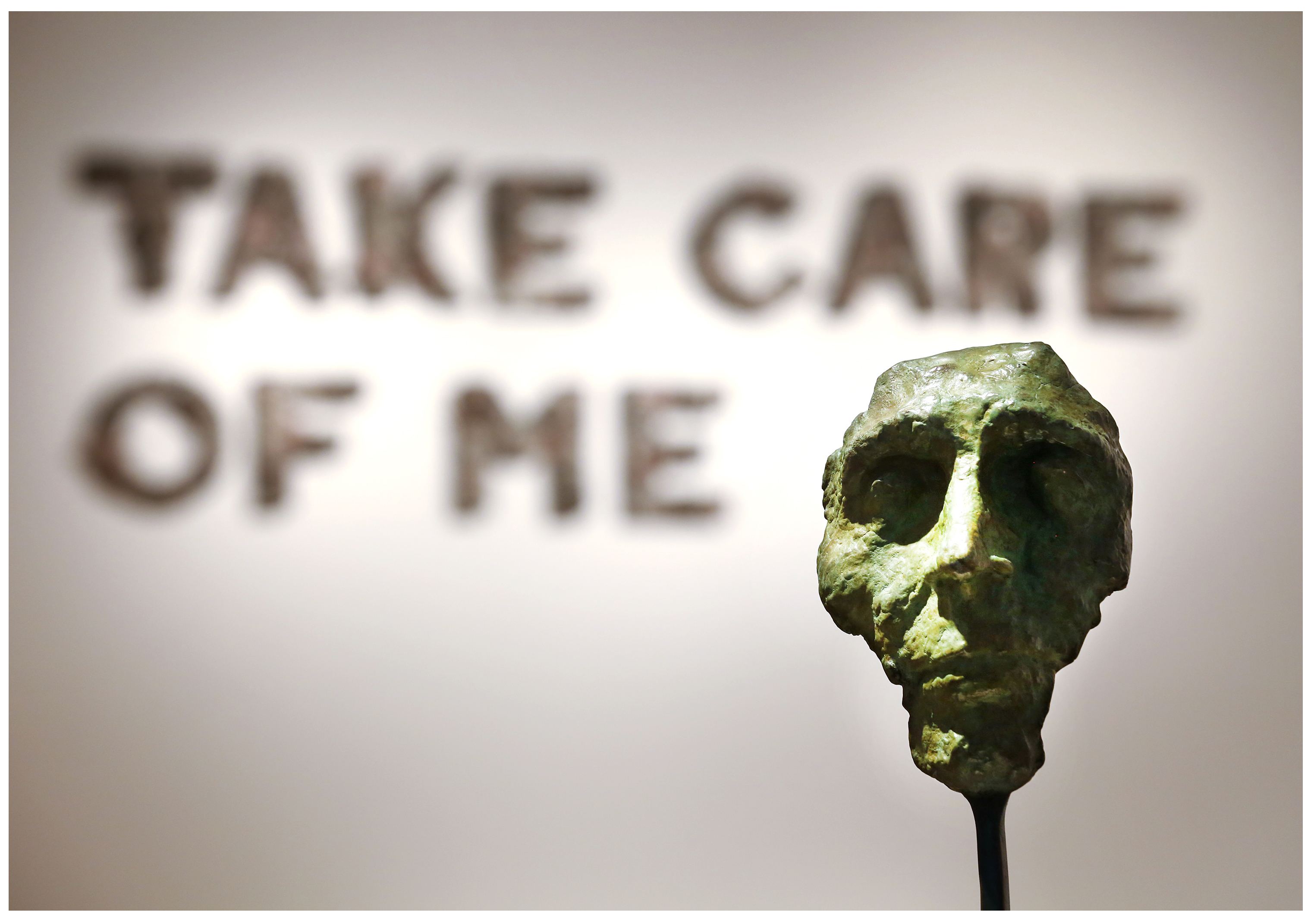

From across the gallery, a craggy face frowns from its place atop a small bronze sculpture by Luben Boykov. It’s the face of Grace Sparkes, the passionate anti-Confederate and lifelong enemy of Smallwood.

Sparkes was known to call Smallwood “Little Batista,” after Fulgencio Batista, the ruthless dictator who ruled Cuba before Castro’s revolution.

Their silent standoff is a fitting welcome to the gallery, because Future Possible is an argument starter.

Through more than 60 artifacts and artworks spanning 70 years, the exhibit takes a fresh crack at questions Newfoundland and Labrador has been grappling with for at least that long.

Eagan joined The Rooms in 2011, and has been the curator of contemporary art for six years. In that time, she has had “thousands of conversations” about Newfoundland and Labrador and its culture. The dialogue, she said, keeps circling back to the same fundamental riddles.

“What does this place look like? What does history look like? Who gets to decide? Who gets left out? How do we move forward?”

Here we are, looking back

Seventy years into Confederation, this is not where Canada’s youngest province hoped to be: facing grim economic prospects, a growing list of seemingly intractable problems, and what feels very much like a crisis of confidence. There have been calls for fresh ideas and new approaches in government. But our elected leaders appear to be stuck in the past, practising politics as a form of tribal warfare and empire building.

Politicians are a product of the community and culture they come from. They won’t challenge their entrenched beliefs until the rest of us do.

Consider, for example, our cherished connection to the land and sea.

Around the corner from Joey’s chair hangs a set of paintings that capture the terror and wonder of the natural world, as rendered by celebrated artists like Frank Lapointe and David Blackwood. For many, that bond with the rocks, trees, and water goes to the heart of what it means to live here.

But the most stunning landscape in the show is Kym Greeley’s vision of the Witless Bay overpass, an asphalt loop drenched in a honey glow reminiscent of an autumn sunset.

Nearby, a Christopher Pratt painting shows the grey concrete of a ruined American military building in Placentia Bay, rising from the earth like it’s been there since the continents formed.

In the midst of it all stands an imposing model of the Hibernia platform, and on the next wall, a painting by Mary Ann Penashue pictures an equally imposing single-engine airplane. The aircraft dominates the snowy Labrador landscape, and dwarfs the Indigenous people waiting to board it.

‘What is the true experience?’

Taken together, these pieces point to alternative versions of our great, ongoing romance with the land and sea. What if that romance is just a convenient bit of propaganda, handed down to justify the claiming, renaming, and continued exploitation of the territory?

In one of the exhibit’s video installations, D’arcy Wilson plays a character she calls Nature’s No. 1 Fan, traipsing through the wilderness, shouting “I love you!” into the void. Nature does not reply.

“Everyone has an idea of what a place should look like,” said Eagan. “But what is the true experience, and what are the stories we lay upon it?”

For those who prefer their wilderness untamed, the waters run full throttle in Robert Pilot’s painting of Churchill Falls and Scott Goudie’s painting of Muskrat Falls, both locations captured before the dams were built.

Elsewhere, a young Labrador artist pushes back against such iconic images. “Instead of focusing on the land, I want people to look at the small and particular,” writes Melissa Tremblett in a statement accompanying her photographs.

The photos narrow the focus to modest, human-sized objects: an abandoned schoolhouse; a tent drying on the beach.

From a single set of hands

Labrador gets smaller still in a pair of Inuit tea dolls and a set of flawless little grasswork baskets. With their minute stitching and precise weaving of grass stalks, these are items that could only come from a single set of hands. They underscore Tremblett’s argument that if all you look for is the “Big Land,” you might miss Labrador altogether.

At every turn, Future Possible messes with familiar and expected images. A giant woman towers over the historic streets of downtown St. John’s. A worn-out trap net is coiled into art. The sinking of the Ocean Ranger is mourned not as an epic industrial disaster, but as a domestic tragedy, leaving ordinary lives shattered in kitchens and living rooms.

The youngest artists in this show have no recollection of the Smallwood era, and the cozy comforts of a handcrafted sealskin throne are not available to them. They’re uneasy, still looking for a version of Newfoundland and Labrador where they belong.

Daze Jeffries frames digital images of items collected on a beach she has known all her life. In an accompanying statement, she recalls childhood dreams of jumping from a beach cliff into the cold harbour water. It could be a sweet outport memory, evoking the contentment of a simpler time and simple place. But for the artist, the dream lingers as a precursor to “my own gender transition as a rural islander.”

Another outport upbringing is recalled in a ceramic sculpture by Daniel Rumboldt. It might be taken for a bird, or maybe a large, exotic seashell, a tribute to the saltwater joys of home. But to the artist, it speaks to his escape from the Great Northern Peninsula, where “I often felt misplaced and outcast due to being queer and being the ‘artist type.’”

“I wanted to tell as much of a varied story as possible,” said Eagan. “With different histories and generations and regions, and different ways of growing up.”

“It’s impossible to write a complete history. So this is just a launching point. I want people to talk about the show, to argue with me, and argue with the works.”

Can a collection of pictures, objects, and artifacts help us talk about where Newfoundland and Labrador goes from here? Eagan acknowledges that art, especially modern art, gets little more than a shrug from many.

“A lot of people look at artworks and they think, this is absolutely absurd.”

But then, Newfoundland and Labrador knows absurdity. The place is famous for it.

This is not your coat of arms

One of the most prominent and striking pieces in Future Possible is a wall projection of the provincial coat of arms flanked by two men. One of them is the artist who created the piece, Jordan Bennett. He displays the government-issued ID granting him Mi’kmaq status.

The other man is fellow artist Jerry Evans, brandishing a letter that denied his application as a member of the Qalipu nation. In Newfoundland and Labrador, apparently, there are no Indigenous people. Only government-approved Indigenous commodities.

“The story of Qalipu identity and Mi’kmaq identity is really an important one,” said Eagan.

“And within an institution like The Rooms, it makes us think. How do we have a space and have a conversation about that changing history?”

Armed and outfitted for hunting, like the romanticized Beothuk who stand guard over a very British-looking shield, video projections of Evans and Bennett blink at us from the wall.

“Talk about absurd,” they seem to be saying. “Over 500 years since Europeans arrived, yet you still can’t acknowledge and respect who we are. So what makes you so certain you know who you are?”

Jamie Fitzpatrick is a writer and broadcaster in St. John’s. His latest novel is The End of Music.

Future Possible: Newfoundland and Labrador Art from 1949 to the Present continues at The Rooms in St. John’s until Sept. 22.