March 26, 2019

This story was first published on March 26, 2019.

Frank Peters was beaten, starved and kept in solitary confinement during the Second World War because he refused to kill.

Peters — my great-uncle Frank — was among the Canadian Mennonites and other pacifists who were jailed in the 1940s because they refused to become soldiers when they were drafted.

"You know, he went into prison a really tall, strong guy who'd been working on a farm, and he was a vigorous man," said Robert Peters, his son.

"The torture that he received in the Canadian military created a permanent back condition he never recovered from."

'We were yelled at and beaten violently with sticks by the officers.'

Peters was jailed for more than two years, one of at least 40 Mennonite men imprisoned in Manitoba after their requests for conscientious objector status were rejected by a Winnipeg judge.

"We were yelled at and beaten violently with sticks by the officers," he wrote about his arrival at a military detention camp, in a 1950 article for a Mennonite magazine that was translated from German by the Mennonite Heritage Archives.

"My cell was six by eight feet with a small darkened window. On one side was a bed. An English Bible was also in the cell. Later I received a mattress and a blanket because of lumbago [severe back pain] which I contracted during my imprisonment."

Few Canadians know about these men who were jailed for their faith-based refusal to fight, and the government has never acknowledged what happened to them.

Peters's son feels it's a wrong that still needs to be righted.

Mennonite pacifists

Frank was my grandmother Melita Schroeder's older brother. They came to Canada in 1923, fleeing the Russian Revolution.

"Had they looked at the record honestly and fairly, they would have seen a man who was genuinely a conscientious objector," Robert said about his dad, who died in 1986.

The Mennonite history of pacifism goes back to the founding of the religion in Europe in the 1500s.

"To be a good Christian was to be a follower of Jesus, and Jesus was someone they saw as a non-violent person," said Conrad Stoesz, a historian and archivist at the Mennonite Heritage Archives in Winnipeg.

A surprising discovery at the archives leaves the reporter in tears:

'I grew up knowing Canada saved my family'

My German-speaking ancestors settled in Mennonite villages in Ukraine more than 200 years ago, after they were promised military exemption.

When the Russians threatened to end that exemption a century later, a group of Mennonite leaders came to Canada and negotiated an agreement in 1873 that promised they would be free to practise their religion here. It included an exemption from military service.

The Peters family — offered alternatives to military service — stayed on their prosperous Russian estates until the 1917 revolution threw the country into chaos.

Five members of the extended family were killed by anarchists in 1919, and my great-grandparents fled the family village with their five children, including seven-year-old Frank.

Conscientious objectors

That's the history my great-uncle carried in 1942, when at age 30, he was "called up" by the Canadian military.

Tall, lean and strong — he helped support his family with the physical labour that kept him working through the Depression — he went before a Winnipeg judge to ask for conscientious objector status, which would give him the right to do alternative, non-military service.

In Ontario, Mennonites were given an automatic exemption from military service, but the Winnipeg mobilization board required men to appear before it to ask for conscientious objector status.

Judge John Adamson, the chair of the mobilization board, was known as staunchly pro-British and a strong Anglican who believed in king and country. He opposed conscientious objection, and made speeches and wrote about why it was wrong, historian Stoesz said.

"He saw his job as to try to get as many of these men [as he could] into the services, and so his questioning at times could be quite aggressive."

My great-uncle Frank, staunchly Mennonite and anti-war, faced that type of questioning.

"The judge said curtly, 'You have a radio and you read the newspaper. You therefore know the issue. Do you want to help us or the Nazis?'" he wrote in Mennonitische Welt, the Mennonite magazine.

"I responded by saying that I wanted to help neither one or the other, but would like to serve my time in alternative service."

More than 10,000 conscientious objectors did alternative service in Canada during the Second World War, working in forestry camps and hospitals, among other jobs. More than 6,000 of those men were Mennonite.

"Some of the men, it was a very simple process — they asked a few questions and that was it," Stoesz said about conscientious objectors who went before the Winnipeg mobilization board. More than 3,000 Manitoba men were given conscientious objector status.

But Adamson berated and belittled some of them, and tried to scare them into the military, Stoesz said.

"He tried to make an example of some of these men."

Arrest and jail

A few days after my great-uncle's request for conscientious objector status was denied by Adamson, he received orders to report to the military.

When he ignored those orders, police arrested him and took him away.

"After a long interrogation [I] was sentenced to six months in prison, after which I was to be handed over to military authorities," he wrote.

He spent his sentence doing hard labour on the prison farm at Headingley Correctional Institute, where there were about 30 Mennonite conscientious objectors, he said.

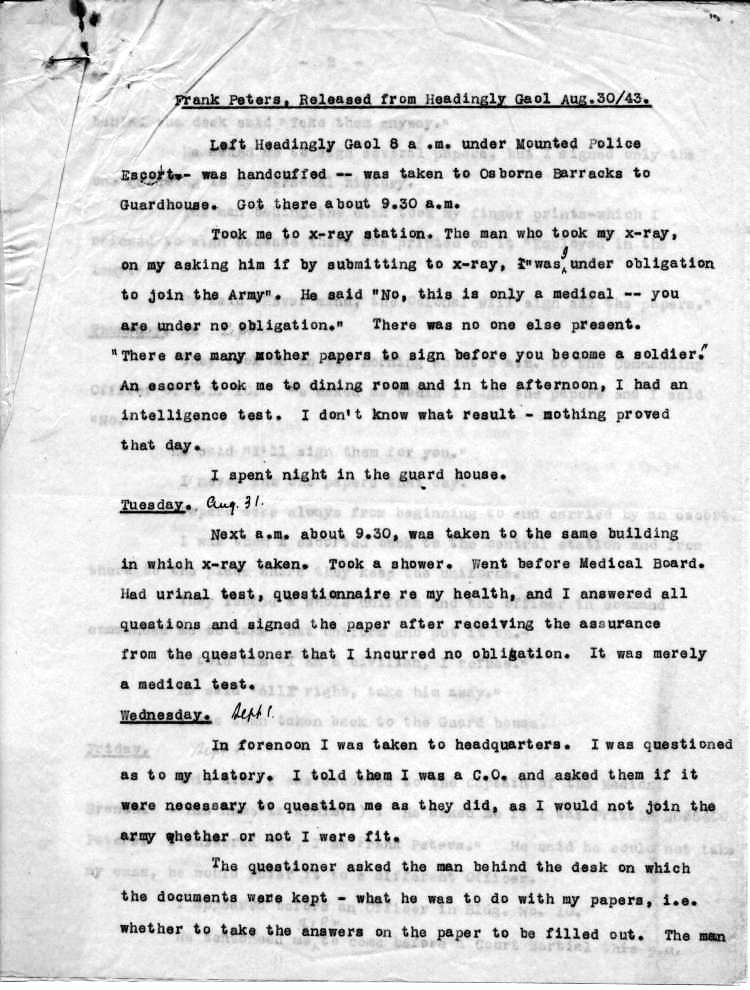

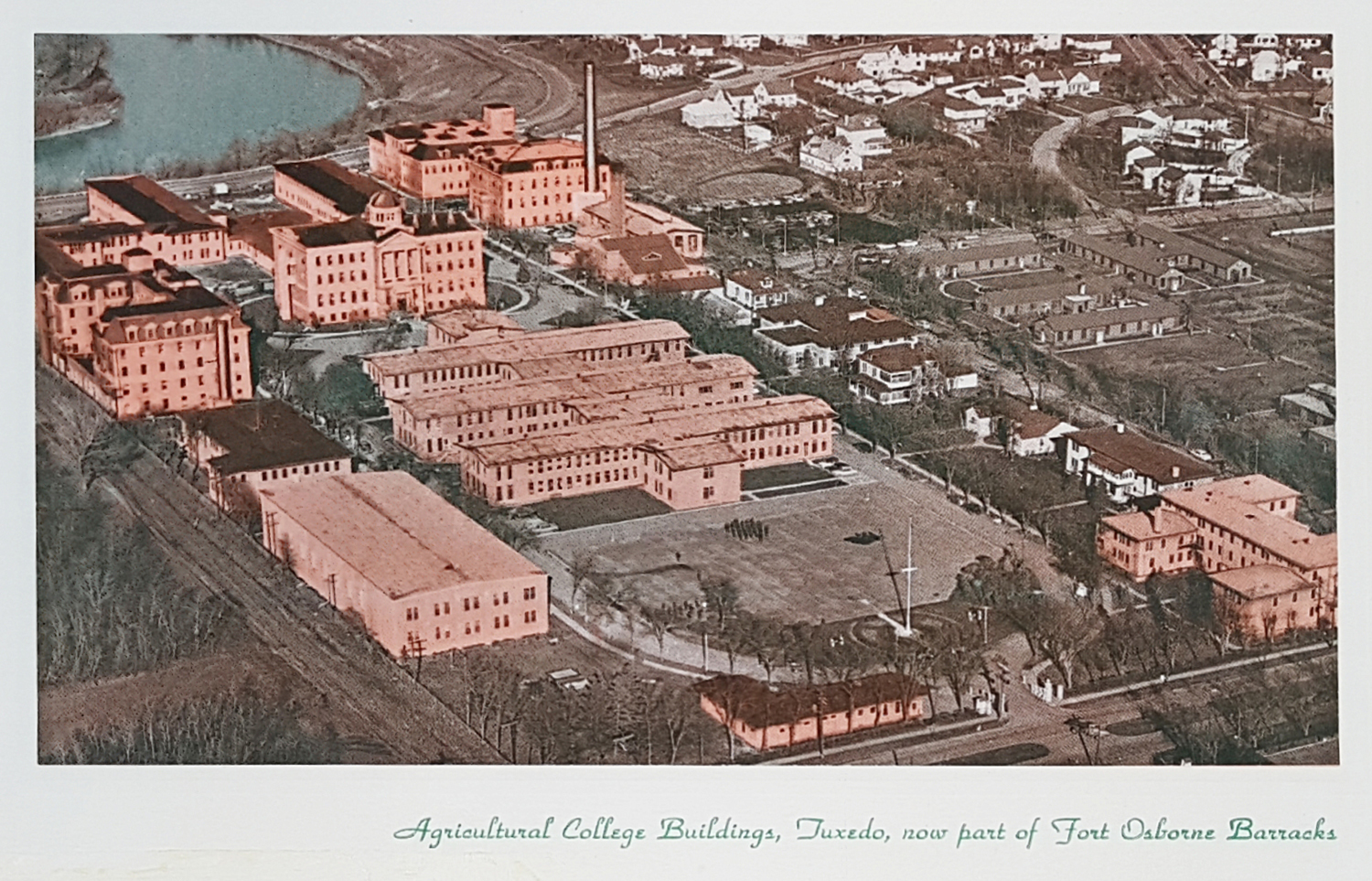

At the end of his jail term, on Aug. 30, 1943, he was taken in handcuffs to Fort Osborne Barracks, in the former Agricultural College buildings in the Tuxedo neighbourhood of Winnipeg.

Read Frank Peters's account of his arrival at Fort Osborne Barracks, as recorded by a lawyer:

Peters told a lawyer who visited him on Sept. 3 that he had refused to sign documents, refused to follow orders and refused to acknowledge he was a member of the military in any way.

He wrote in Mennonitische Welt that he was advised to undergo another physical exam, which would give him conscientious objector status.

"However, after the medical examination, I was informed that I was now automatically a member of the military. I was now a soldier."

Frank Peters, soldier

Peters still refused to follow orders, so he was put before a court martial.

He was sentenced to a year of military imprisonment.

"Arriving in the detention camp, together with another soldier, we were yelled at and beaten violently with sticks by the officers," he wrote.

He was ordered to appear for training drills but didn't go "on the excuse that I was not a soldier."

"The punishment for this was three days of bread and water," he wrote.

"I received a pound of bread and as much water as I wanted. During those six months I was on this ration for 108 days."

'He couldn't straighten up, because his back was so bad.'

Peters was held in solitary confinement, and he wasn't given any bedding at first.

He told the family at one point, his military cot was removed, and he was forced to wash the floor of his cell, so there were times when he slept on cold, wet cement in nothing but summer army fatigues — the only clothing he was given.

The family wasn't allowed to visit him, but my grandmother, Melita Schroeder, finally went anyway, her two young children with her.

My grandmother was told she couldn't see her brother, but she said she would wait.

"They eventually relented. We were there for hours and hours before that happened," said my dad, Henry Schroeder, who was a toddler at the time. He doesn't remember the visit, but his mom told him about it.

"He was in terrible shape.... He couldn't straighten up, because his back was so bad."

Listen to Henry Schroeder talk about his mother's visit with her brother Frank:

In February 1944, still in military prison, Peters learned he would be allowed to appeal his case in civilian court.

After he received that news, his treatment at the hands of military officials improved, he said.

However, his case failed in civilian court, and he was again put before a military court, he wrote.

That court sentenced him to another 18 months in jail, and he was returned to Headingley in 1944.

The return to Headingley, where "only four of our Mennonites" remained, with two more returning during Peters's imprisonment, was an improvement.

"After all the days of starvation in the detention camp, food was my supreme interest and within two months I had gained 40 pounds."

The Mennonite men counted the days between letters and visits — and the days left in jail.

"The daily greeting to each other were the number of days still left in our prison sentence," Peters wrote.

Freedom

The last five months of Peters's 18-month sentence were cancelled, and in 1945, he was released.

He'd lost more than two years of his life, and earned a dishonourable discharge and a prison record.

His only surviving sibling, Helen Fleige, said it wasn't easy for him to find work after that.

"It sort of hurt him, I think, in that how he could earn a good living?" she said. "It was always there on his record."

His son Robert and my dad both said although he returned to First Mennonite Church with unbroken faith, the church never acknowledged the sacrifice he made for his beliefs.

A few men who had joined the military were welcomed back with a church service of thanksgiving for their safe return, but nothing was done when great-uncle Frank returned, a physically broken man.

'He saw himself as having not defended the country, but having defended the faith.'

"He thought that the service for the military people returning who had served their country and made sacrifices for their country was a wonderful thing," my dad said.

"But he saw himself as having not defended the country, but having defended the faith, and having done what he did to defend the faith, and in a sense that wasn't recognized."

My dad said even as a boy, he sometimes felt like people were a little embarrassed about uncle Frank and his wartime experience — as if he'd made a big fuss about his faith unnecessarily.

But my great-aunt Helen said he did it for the sake of the other, mostly younger men who went before Adamson.

"He decided that if he went to jail, then they would realize that ... we meant what we said — that we didn't kill," she said.

"He figured ... if he would succumb to them if they threatened jail, then none of the other boys would be safe either, so he went to jail."

'Peace heroes'

Stoesz, who is Mennonite, considers men like Peters an inspiration.

"Every time Canada has been involved in a conflict, there have been people who said no. We need to hear their stories too," he said.

"If we want to move the world to a more peaceful existence, we have to have examples of peace heroes."

Stoesz has built a website about conscientious objectors, digitizing and uploading the Mennonite archives' documents about alternative service.

My father also feels his uncle's story needs to be told. He wrote a play based on uncle Frank's wartime experiences, called For the Greater Glory; it was staged by Winnipeg Mennonite Theatre in 2014.

Robert Peters says the Canadian government owes his dad and the other conscientious objectors an apology.

"Beyond that, I hope there will be some legislation passed that's more adequately protective of people of conscience and their rights."

He'd also like to see these men given a more prominent place in history.

"I think these issues unresolved still need to be resolved. I think healing is possible."

"He was the type of person who knew what he stood for, and was courageous enough — stubborn enough, whatever you want to call it — to walk in his best lights, I think, all his life."