November 28, 2018

At least once a year, a small support group gathers to remember a terrible event and to heal.

They’re survivors — in different ways — of a floatplane accident that occurred nine years ago in the B.C. Gulf Islands.

Barbara Glenn, 65, Francois St. Pierre, 42, and Patrick Morrissey, 57, share finger food, friendship and forgiveness in Glenn’s Surrey, B.C., dining room.

All three say they don’t know how they would have survived otherwise.

![Pilot Francois St. Pierre shakes hands with widower Patrick Morrissey, while survivor Barbara Glenn looks on. (Nicolas Amaya, CBC News)]](https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/craft-assets/images/trio-go-pro-handshake-CORRECTED.jpg)

"If I didn’t have this — if I didn’t ever get to know Francois as a person, I’d just harbour a grudge against him and couldn’t forgive him,” says Glenn, referring to St. Pierre.

“My life would be totally different.”

St. Pierre was the pilot of a SeaAir flight that crashed shortly after take-off from Saturna island on Nov. 29, 2009. Glenn was one of seven passengers.

All survived the impact with the water, but the de Havilland Beaver floatplane quickly sank 14 metres to the bottom of Lyall Harbour.

Glenn and St. Pierre were the only two survivors.

Six others on board drowned — including Barbara’s husband, Tom.

Patrick Morrissey wasn’t onboard — but lost his wife, Dr. Kerry Telford-Morrissey, 41, a maternity doctor and their six-month old daughter, Sarah.

Cindy Schafer, 44 and Bruce Haskitt, 49, of California — part-owners of Saturna’s Lighthouse Pub — and Catherine White Holman, 55, of Vancouver, also died.

St. Pierre has never spoken publicly about piloting the tragic flight — until now.

“I did feel like that maybe it was something that was unforgivable,” said St. Pierre. “Like I could never bring them back.”

Nine years after the crash, Transport Canada has yet to act on safety recommendations put forward by the Transportation Safety Board in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Those recommendations include a requirement that rapid escape exits such as pop-out windows be installed in float planes and that personal flotation devices (PFDs) be worn by passengers, instead of stored under seats.

Some operators made the changes voluntarily. But Transport Canada has not brought in mandatory regulations.

St. Pierre has wrestled with grief and guilt, even though the Transportation Safety Board investigation into the fatal crash found a series of unforeseen events combined to cause it.

Gusting winds on take-off in Saturna’s Lyall Harbour forced St. Pierre to make a tight turn. An out-of-commission alarm in the aircraft failed to give him advance warning of an impending stall.

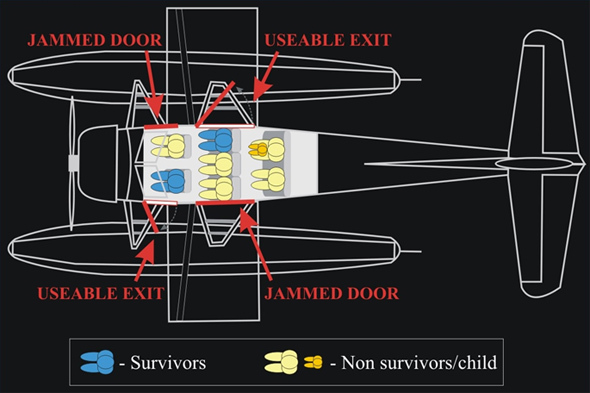

St. Pierre was able to level out at the last second before the plane hit the water, but the force of the hard impact on choppy seas drove the plane’s pontoons up into the wings and jammed two of the aircraft’s four doors.

St. Pierre and Glenn were badly injured but escaped through doors that cracked open beside them as water poured into the cabin.

“You’re just kind of stuck in a tin can, trapped," recalled Glenn. “My survival reaction was ‘how do I get out of here?’ I could see under water on my side there was light … I swam for the light and I got out.”

“I just assumed everybody else would have seen me. Nobody came out.”

Glenn swam around the sinking plane looking for other survivors but found only St. Pierre struggling to open one of the jammed doors.

As the plane slipped beneath the waves, they clung to its docking bumpers to say afloat.

“Barbara and I say, ‘maybe we could have done this or we could have done that,’ but at some point, those people are gone,” said St. Pierre.

One year after the crash, St. Pierre attended a memorial where he met Glenn and Morrissey and formed a lasting bond.

“Sometimes, I really felt numb through the years. But they embraced me,” said St. Pierre. “I think we all came together stronger and bigger persons.”

Glenn reaches over and squeezes his hand. They spent weeks in hospital recovering from their injuries. Both suffered fractured vertebrae, sternums and broken bones.

“There’s a bond we share, because we experienced it together and we’ve had the loss together,” says Glenn.

“So, when we see each other, I guess, to me, it’s like men who have been through the war together.”

Morrissey credits the group with preventing him from plunging into a deep depression over the loss of his wife and infant daughter.

He picks up on the war theme.

"Even though I wasn't a survivor, I still feel I was in the battlefield with them," he said.

"You're all wounded from it. It's the wounds we're all grappling with together."

Asked what he gets out of the group support sessions, he has a simple answer: "Peace."

All three in the group, say they have received comfort and support from Transportation Safety Board investigator Bill Yearwood, who reviewed the crash.

Yearwood is currently on leave from the TSB and not able to comment.

Since the Saturna tragedy, there have been at least two similar crashes where occupants survived, then drowned.

Frustrated by the nine-year delay, worrying about others as they try to heal themselves, the trio vow to keep meeting and keep healing.

“It’s like a lifeline,” says Barbara.

“We’ve got a friendship. And the bond is always going to be there.”

Tomorrow: What the Transportation Safety Board has to say about its long-ignored recommendations to improve seaplane safety and why the seaplane industry has resisted some of the proposed regulatory changes.