August 29, 2018

The road to the Ironman World Championships in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, is filled with crushing waves, endless rolling hills and more heartbreak than a high school romance.

If triathlon was hockey, this would be the Stanley Cup finals.

But for Ryan Brown, a 31-year-old former hockey player turned multi-sport superstar from St. John’s, just getting to race is a win in itself.

“It’s a long day, it’s a long distance — but anything can happen and anything is possible if you put your mind to it,” Brown said.

That’s because scoring an invite to Kona (like Madonna, it goes by a single trademarked name) means being one of the fastest in the world. And like most Ironman races, there are few spots for amateurs.

“Every year, the amateurs are getting better and better, so it’s becoming more and more difficult,” Brown said.

“The sport has evolved and become very, very competitive. The end goal for a lot of these triathletes is to get to Kona.”

Rough road to Kona

The difference between standing on the starting line and following the race online comes down to mere seconds.

For the last three years, Brown has come painstakingly close. Last year, he was 73 seconds short of qualifying. The year before that, he was off pace by 23 seconds; and in 2015, he was just 18 seconds shy.

It was at an event earlier this month in Mont-Tremblant, Que., that Brown made his fourth attempt at Kona, competing against more than 2,200 others in swimming, cycling and running.

For Brown to qualify, he’d have to be among the top two amateur racers in his age group. It was an ambitious attempt, but not only did he pull it off — he excelled.

Crossing the finish line with a time of 9:14:07, Brown didn’t just snag the fourth top spot among amateur racers, he also finished 15th overall — that’s including the pros.

Impressively, amateur Ironman participants compete almost shoulder to shoulder against professional racers. In Mont-Tremblant, the pros had just a 10-minute head start.

For Brown, the result was an emotional one, not just because of the years — and thousands of hours — spent training, but because one of his biggest fans and supporters didn’t get to see him do it: his sister Cori.

“My younger sister suddenly passed away. It was very, very unexpected and shocking news,” Brown said from his home in St. John’s.

Cori Brown died in early February, at the age of 25.

“She would come to every race and cheer me on. She was very much inspired [by] what I did, and losing her was a big loss to our family,” Brown said.

But Cori did see her big brother come close to his Kona dream during a 2017 qualifying race in Mexico. Brown said his sister sent him an encouraging text, pushing him to keep trying for the Ironman World Championships. That text, he said, helped fuel him to the finish line.

“This [Mont-Tremblant] race had a little bit of extra special meaning to me and and my family,” said Brown.

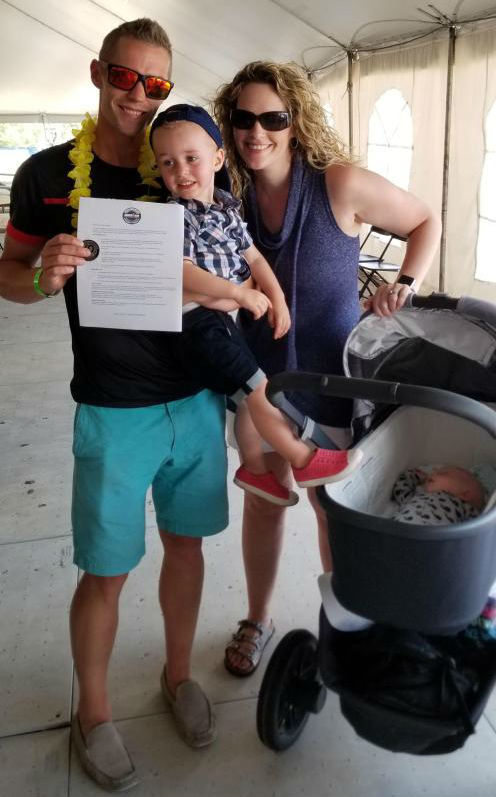

“Not having her at the finish line was so emotional this time around. We had made our qualification to Kona. We did it.”

Individual race, family affair

Despite being the sole competitor, there is no “I” in team for Brown.

His wife Gill gave birth to the couple’s second son in July, so Brown’s racing has meant a lot of time management and sacrifice for his family.

Brown, who's a subsea engineer with Husky Energy, puts in the equivalent of part-time job hours into his training — anywhere from 18 to 20 hours a week.

“[Gill] has been a huge part of my success and I can't thank her enough,” said Brown.

“There is no way I could do any of this without her, without her support and without her encouragement. Deep down, she knew I could it.”

Brown’s sons, Aidan and Ethan, along with his parents, were on hand to see him achieve this Ironman dream.

With one goal accomplished, Brown now has to prepare for the Hawaii long-distance race. But Brown isn’t feeling the same pressure he usually feels before an Ironman race.

“The nerves aren't there to put stress on the body. When there's no stress in the body, you stay relaxed [and] you can perform quite well,” said Brown.

“It’s definitely going to be challenging and we are going to put a lot of hard work in. I think I’ll be surprised by the results.”

Can't outrun the weather

Brown acknowledges that training at home has unique challenges.

St. John’s and ideal weather for outdoor training are about as rare as a piebald moose sighting going viral on Facebook.

“Living in this province for training purposes, it’s very difficult. A lot of the time, it’s raining and it’s cold, and it’s tough to get outdoors,” he said.

“In this sport, you swim outdoors, you bike outdoors and you run outdoors for so long it becomes very, very challenging.”

As a result, he spends 90 per cent of his time training indoors.

It's not just the weather that makes training difficult. The triathlon season in Newfoundland and Labrador is very short, with races happening in late July and August.

Brown is hopeful that competing in such a high-profile race like the Ironman World Championships will help boost his sport in the province.

“It’s pretty incredible to even be able to be up there with the top amateurs and qualify for World Championships living in Newfoundland,” Brown said.

“This is a pretty big deal.”