Thousands of Montrealers walk by it during their daily commutes without so much as a passing glance. They likely don’t know it’s the last one of its kind in the province.

There was a time, though, when there was a photo booth at nearly every station in Montreal’s Metro system. They were first installed for Expo 67, shortly after the Metro first opened to the public.

Now, there’s only one analog photo booth left in Quebec — it’s at Place-des-Arts Metro station in Montreal — and only six others remaining across Canada. The other soon-to-be-defunct analog booths can be found in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

“If you want to use ’em, use ’em now. Their days are numbered,” says Jeff Grostern, president of Auto Photo.

His grandfather founded the company, which owns and operates Canada’s last analog photo booths in addition to its 180 digital booths.

It’s easy to forget, but there was a time when the service provided by photo booths was not only a novelty but a necessity.

The booths served a practical purpose for decades: quick, cheap, quality ID photos.

“If you needed an instant photo, this was the way — the only way,” Grostern says.

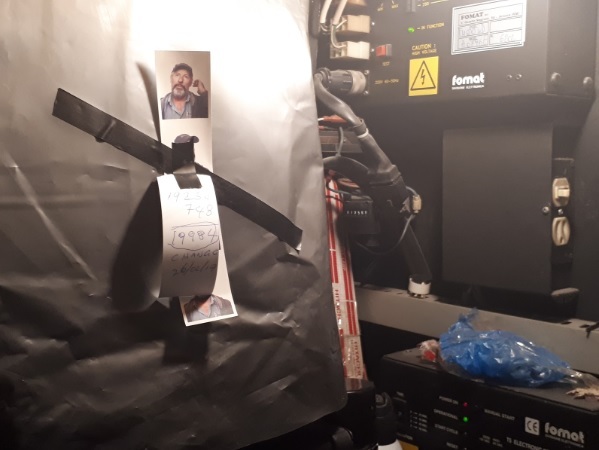

Grostern unlocks the heavy padlock inside the booth at Place-des-Arts Metro station to strip back the mystery and magic, unveiling the whirring machinery and liquid chemicals that once revolutionized the photography world.

The technology inside the booths is simple and straightforward and, aside from some fine-tuning over the years, hasn’t changed much since the booths were mass manufactured in the 1940s.

After you put the coins in the machine, the camera is cued. A reel of light-sensitive paper feeds down into the camera box. After four flashes, that paper gets pulled down into chemical tanks to develop the images you posed for. Last but not least, the strip gets delivered to you via the little metal chute, still wet from the developing chemicals.

Chemical booths can be high-maintenance, especially compared to digital ones: a technician has to come by weekly to replenish the chemicals and ensure everything is running smoothly.

Photo booth faithfuls

The booth’s owner and technicians are not the only ones still using this machine in 2019.

Amber Dearest, a self-described photo booth enthusiast, makes regular pilgrimages to the Place-des-Arts booth twice a year: on her birthday, and on her “Montreal-iversary” — the anniversary of the day she moved to the city more than 10 years ago.

“It’s literally a booth where you can close a curtain and hide away in a busy public place,” she says.

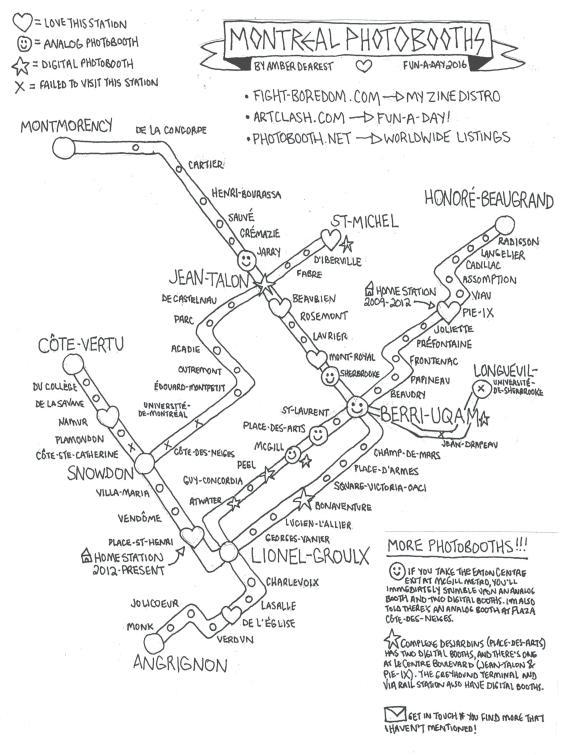

Over the years, Dearest took it upon herself to chart the slow decline of analog booths in the form of a map, available as the fold-out centrefold of one of her many zines.

“It’s one of my secret worlds.”

Another person who shares Dearest’s enthusiasm for photo booths is Meags Fitzgerald, a graphic novelist who, in 2012, published Photobooth: A Biography. It’s all about traditional analog photo booths.

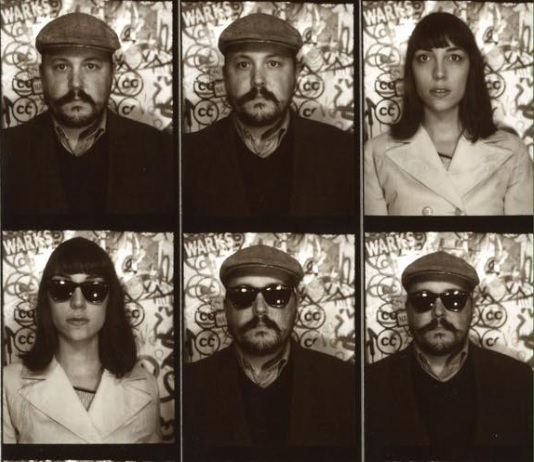

Besides having her photo taken, Fitzgerald has also used booths for all kinds of artistic projects, such as crafting animated short films or capturing drag king alter egos.

Just like Dearest, Fitzgerald is bracing for the day when colour analog booths will be gone forever.

“You’ll walk up to a spot in the mall or at the bus station to where you knew there used to be a booth, you’ll hold your breath and you’ll see ... it’s gone now.”

Their imminent disappearance is due not only to the rise of accessible digital photography tools but also to the fact that the paper on which photo booth strips are developed stopped being manufactured in 2007.

So when the paper inside Canada’s last seven booths runs out, that will mark their end.

Colour vs. Black and White, Digital vs. Analog

While Fitzgerald and Dearest both know the days are numbered for their beloved Montreal booth, chemical booths are still in operation around the world, particularly in Europe.

Auto Photo sold many booths that were used in Canada to museums, galleries, artists and businesses in European cities like Berlin, Paris and London.

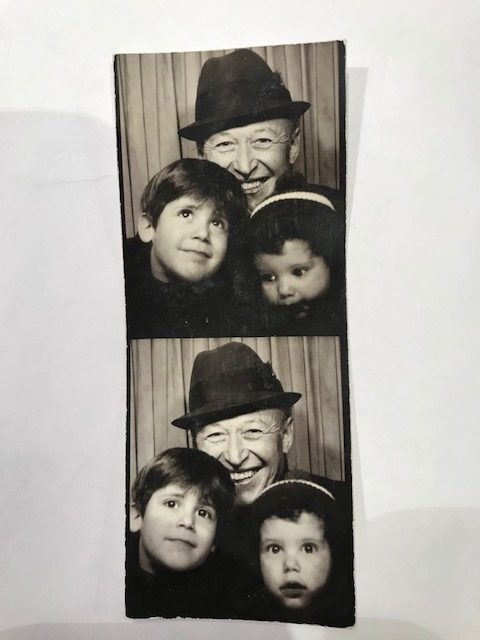

You might even spy Grostern’s childhood face outside some of them. He, along with his family members and staff at the company, would be enlisted to pose as models.

“As kids, that was one of our requirements: we had to come in and take photos. We didn’t necessarily like it, but our father used to set us up because we needed models.”

The tradition continued for nearly 50 years. In the 1990s, Grostern would enlist his own family, including his wife and children, to pose for test strips.

“Funny enough, my daughter [Jessica] was travelling in Amsterdam for a few days and just happened to cross paths with one of our old booths … and saw her mother’s picture on it.”

Grostern says there will always be a demand for black-and-white booths, particularly in the film industry.

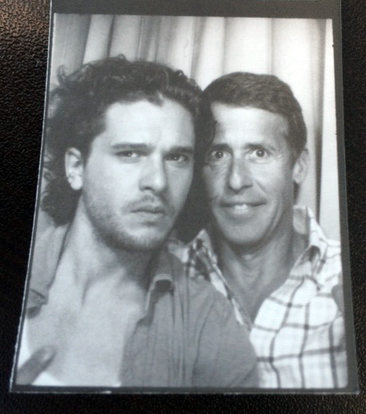

The paper for black-and-white strips still exists, and Grostern gets requests from movie studios to use some of his booths — like the time Kit Harington, the actor now best known for his role as Jon Snow in Game of Thrones, was in Montreal filming the Xavier Dolan film The Death & Life of John F. Donovan.

From analog to digital

As for the future for Auto Photo, digital booths have been a key part of its business for a decade now. Grostern says the company operates 180 digital ones — but aficionados are quick to point out that the process isn’t quite the same.

Some of the preferences are purely aesthetic. “The bright flash [in the analog booth] is very forgiving,” Dearest points out with a laugh. “I feel like it washes out some imperfections.”

Fitzgerald says once analog booths are gone, something will be lost in the way we capture and document our “real” lives.

“You know when you're with your friends and you're taking some selfies on your smartphone? You're probably going to take 20, and then pick the best one where everyone looks great,” she says. “But there's something about having your best and worst days documented that I think is really important and far more honest about our human experience than the way the records we're leaving for our grandchildren look.”

“The iPhone killed the photo booth,” says Grostern.

“The next generation won't get to experience it — our kids’ kids won’t know what a photo booth is.”