October 2, 2021

Gerri Sharpe touches the lines and dots tattooed near her eyes.

"I got these ones here for being from Gjoa Haven," she said, referring to the small hamlet in Nunavut's Kitikmeot region on King William Island.

They were the first kakiniit, or traditional Inuit tattoos, Sharpe got inked on her body.

"At the same time, I had my V done."

This tattoo is a popular marking on Inuit women and it varies in shape, depending on the individual's preference. While a chosen shape may look the same on different people, each version symbolizes something different and personal for the woman wearing it.

"From there," Sharpe continued, "I actually had my fingers done. This was the second-most painful… the fingers in between there," the 51-year-old said, as she rubbed the markings. "Just think of many, many, many paper cuts, all at the same time."

Sharpe's most painful tattoo, however, is the one she had done on her chin, closest to her lips. She also has tattoos on her chest, wrists, hands and forearms.

They tell her story. "Every single one of them means something."

Kakiniit is an ancient Inuit practice that was nearly lost when the Catholic Church banned it a century ago. Sharpe says the church saw it as evil, and because it was not part of Christianity, it had to stop.

"So there was a lot of shame" around the tattoos, she said, which resulted in women "talking about them behind closed doors."

Sharpe grew up in Gjoa Haven, about 1,000 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife, where she now lives. She says it was "commonplace" to see women with tattoos in Gjoa Haven. "I remember being just in awe of them."

When Sharpe, around the age of 10, started asking the women questions about their tattoos in public, she wouldn't get any answers. And that confused her. But when she visited an elder at her home, the woman exploded with information and happiness in discussing them. "And that's when she said that you're not supposed to talk about them in public."

WATCH | Gerri Sharpe on learning the history of the tattoos:

Sharpe absorbed all the oral history she could about the kakiniit from her elders, including the meaning behind the lines and dots that told of a woman's rite of passage.

"Once upon a time, you could look at a woman's face [and] you could know who her family was, where she was from, what her achievements were and her place in the community," said Sharpe. "The whole thing was told on her face."

'A connection to our history'

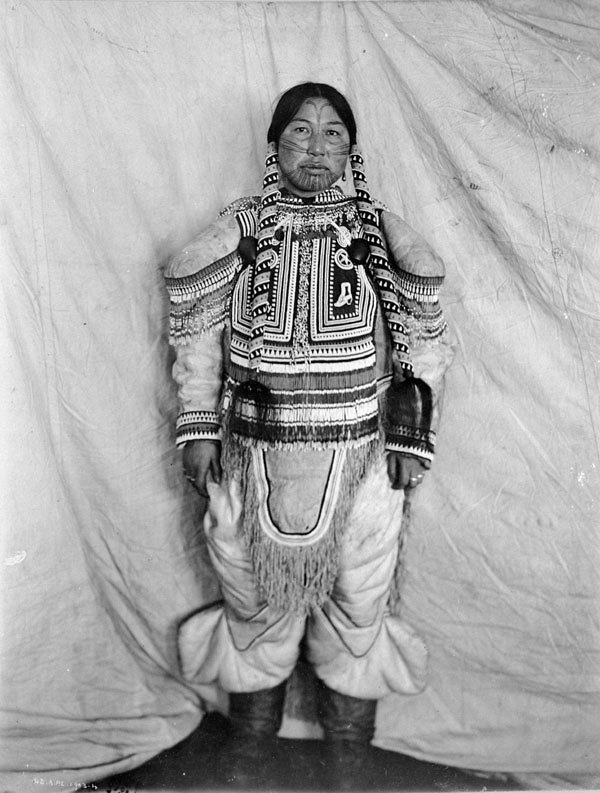

The traditional tattooing method used thread-like material made of caribou sinew that was soaked in seal oil and soot, poked with a bone needle and then sewed into the skin.

That method is still followed today, but with needle and ink. Inuit women also go to tattoo parlours familiar with a tattoo gun. Either way, the kakiniit is making a comeback.

"They have proud, proud roots in Inuit culture," Sharpe said with great passion. "They're not a symbolism for everybody. So while they do represent women, they represent Inuit women."

Like 23-year-old Jaime Dawn Kanangana Kudlak.

"I got my traditional tattoo right before my 18th birthday," she said. "I think about a week before — yeah, I skipped art class for it."

Kudlak, who lives in Yellowknife, comes from a family of tattooed women. Her aunt and grandmother, who live in Ulukhaktok, N.W.T., and another aunt in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, all have the same kakiniit.

"My Auntie Emily, I'm very close with her. She's always been a part of my life. She got a tattoo, the same tattoo that my great-great-grandmother had."

Kudlak says it's a way of showing who she is: part Inuk and feeling a desire to connect with that side of her family. "It's just part of my identity."

WATCH | Jaime Kudlak talks about getting her traditional tattoo:

That feeling is mutual for 31-year-old Tanya Roach. She says the intricate lines in the shape of a V on her chest represent a characteristic of what it is to be an Inuk woman.

She says she got the "chest piece" a few years ago, when her son, Kaize, was just a toddler. He's now 11. "I wanted this image to be very normal growing up for my son and myself."

Roach says she chose the V on her chest so she can see it every time she looks in the mirror, but can also cover it up when she feels like it.

Roach spent 15 years in the Northwest Territories' foster-care system and didn't grow up immersed in Inuit culture.

"When I became a mother, I didn't have a value system that would help me raise my son. And so that's when I looked to our culture," she said. "That meant researching traditional knowledge, practising throat singing and tattoos."

Roach's kakiniit gives her the confidence she's been looking for in finding her identity.

"I feel humbled and I feel strong at the same time, and I feel connected to something bigger than myself — to the North, to the people, to a history that's thousands and thousands of years old, and not just the 15 years [I spent] in the system as a foster kid."

To Gerri Sharpe, her kakiniit "represents strength, resilience.… in my mind, [it] confirms that I'm Inuk."

And she isn't done getting traditional tattoos. Her next marking will be on her face again — this time on her cheeks, in the shape of the kakivak, a traditional Inuit hunting tool she says is another homage to Gjoa Haven. She also wants to get kakiniit on her shoulders.

Said Sharpe, this tradition "gives me a sense of belonging. I can go anywhere in Canada and any Inuk around me will know that I'm Inuk. That wasn't always the case before my tattoos. It gives me a connection to our history."