November 12, 2019

Glenn Mackey boarded the MV Lyubov Orlova in St. John’s Harbour on July 2, 2010, expecting to conduct a routine ship inspection.

But the Transport Canada inspector's visit quickly became anything but routine.

He noticed the crane for the lifeboats was broken and the fire doors were defective.

His notes from that day describe the crew's emergency drills as a "fiasco."

On top of that, the ship's backup compass was inoperable and its compass deviation log was "suspiciously accurate."

At one point, according to Mackey's notes, beads of sweat appeared on the radio officer's head as he explained that the compass was wandering "just a little bit, but OK."

Then, the captain got involved.

"He led me out from his cabin to another cabin on the same deck," Mackey wrote in an email to his colleagues, obtained by CBC News under the Access to Information Act.

"He closed the door behind him and immediately presented me with a pen and what looked like a piece of cardboard and asked me to write down how much money I wanted."

Mackey wrote that he went straight to the police to report that he had been bribed.

The Russian captain claimed there was no bribe; his English had simply been misunderstood.

Mackey's visit proved to be the beginning of the end for the Lyubov Orlova, a 4,251-tonne Arctic and Antarctic expedition cruise ship with a capacity of 110 passengers and 70 crew. The 2010 Arctic summer cruise season would be its last.

Within two months of Mackey's inspection, the Lyubov Orlova and its crew would be abandoned in the harbour by the vessel's owner, as lawsuits and liens piled up.

In fact, it would be nearly three years before the Lyubov Orlova would leave St. John's Harbour.

When it finally did, the vessel, named for a Soviet movie star, was described in international headlines as a "cannibal rat-infested ghost ship" drifting on a crash course toward Britain.

But the Lyubov Orlova never made it across the Atlantic; it's believed to be rotting somewhere at the bottom of it.

The Lyubov Orlova's journey from cruise ship to ghost ship left financial hardships, a humanitarian emergency and a political controversy in its wake.

In an odd twist, the debacle also inspired a song by Canadian rockers Billy Talent, as well as a Swedish EDM track, and even the name of a French metal band, Orlova.

For two cruise seasons — 2008 in the Canadian Arctic and 2009-10 in the Antarctic — I lived and worked aboard the Lyubov Orlova. During that time, the ship was my entire world.

Nobody would have described the Lyubov Orlova as luxurious, but it was clean and functional. Passengers could have a drink in its tiny, faux-wood-panelled bar, with its emerald green- and gold-striped booths and small mural honouring its movie star namesake.

They could roam outside from the bow to stern, where there was a small, usually empty, swimming pool.

Seeing the ship meet such a tragic end served as an inspiration of sorts for me. I wanted to learn everything I could about its history. Who owned it. Why they abandoned it. How something like this could have happened.

Uncovering that story would require delving into some Soviet and post-Soviet history, the secretive world of offshore financial schemes, and the checkered histories of two Russian men named Oleg.

Early years

The Lyubov Orlova was built in 1976, part of a fleet of eight sister ships commissioned by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev as a make-work project for a Yugoslavian port.

Each was originally named for a Soviet actress, and Lyubov Orlova was one of the empire's most beloved stars, appearing in 11 classic films between 1934 and 1960.

In 1950, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin bestowed her with the Soviet Union's top honour, the State Stalin Prize. And in 1972, a minor planet was named after her — the 3108 Lyubov.

Only two sister ships, the Sea Adventurer [nee Alla Tarasova] and Klavdiya Yelanskaya, are still sailing today. The rest have either sunk or been broken up for scrap.

The Lyubov Orlova was originally owned by the Far East Shipping Company, which used it to ferry passengers along the eastern coastline of the Soviet Union, mostly around the Vladivostok region.

For a time, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the ship made trips to Japan.

Peter Golikov, a captain who knew of the Orlova from his time working for the Far East Shipping Company, said people would buy Japanese second-hand cars and import them back to Russia.

Golikov went on to become part owner of U.S.-based cruise company Quark Expeditions, which chartered the Lyubov Orlova for Antarctic trips starting in the early 2000s.

"She was bringing quite a lot of money for the company, so we were happy," he said. "And surprised with what happened to her later."

Golikov said as far as he remembers, Quark was ready to charter the ship for the 2010-11 Antarctic cruise season.

Stop sail

A company called Cruise North Expeditions was chartering the Lyubov Orlova in the summer of 2010 for trips up the coast of Labrador and Baffin Island, and in the High Arctic to destinations such as Resolute and Beechey Island, where three members of the Franklin Expedition are buried.

Ultimately, Mackey's police report against the ship's captain went nowhere. However, Mackey's list of deficiencies with the Orlova remained outstanding. Transport Canada issued a stop-sail order, which essentially halted cruises until those problems were rectified.

After cancelling one trip, Cruise North decided to cover the cost of the repairs on behalf of the ship's owner, the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co.

Cruise North's president at the time, Dugald Wells, said it was normal to sometimes cover expenditures on behalf of the owner as the season progressed.

"But there was an accumulating balance owing to Cruise North that was … getting pretty significant and the owner couldn't repay us," he said.

The company's contract to charter the ship was wrapping up its fifth and final year. Wells knew if the Lyubov Orlova sailed out of St. John's Harbour into international waters that fall, he might never see his money.

So he decided to file a $250,000 US lawsuit against Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. The court approved an order to have the vessel seized for collateral.

"We were hoping that there would be a quick settlement of the whole thing," Wells said.

"But there wasn't."

Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. filed a statement of defence and countersued, claiming the Lyubov Orlova was "tight, staunch and strong, properly manned and seaworthy at all times," and that Cruise North had miscalculated costs of the charter hire.

Therefore, stated Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., the ship was "wrongfully arrested," resulting in damages to the shipping company.

Cruise North denied these allegations, pointing to the fact it had to cancel a cruise earlier that summer due to the ship's deficiencies.

The next spring, the Lyubov Orlova remained docked in St. John's, its wheelhouse windows papered with liens.

"The boat and its [sister ships] do NOT have a good history," said an email between Transport Canada directors at the time. "I can hardly wait to see how this one turns out."

Abandonment

Cruise North's lawsuit precipitated an avalanche of other claims against the MV Lyubov Orlova, the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. and other interests in the ship, seeking a combined total exceeding $2 million US in damages.

The St. John's Port Authority sued for hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid dock fees, security costs and repairs as the ship listed precariously for months, taking up valuable space in the harbour. Harbour officials worried about environmental damage should it sink, so they spent tens of thousands of dollars just keeping it afloat.

Cruise North Expeditions, also named in the suit, said in a statement of defence that berthage charges for the ship were for the benefit of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., not the charterer.

Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. didn't file a statement of defence.

A customs brokerage firm also came forward looking for about $35,000 US, partly to recoup security costs it paid to Immigration Canada for a Russian crew member who walked off the ship claiming refugee status.

In a statement of defence, Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. said it carried no liability for the crew member, who it claimed was working in Canada under a permit sponsored by Cruise North Expeditions.

Cruise North Expeditions, also named in the suit, maintained the Russian crew was the responsibility of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., as they were entirely under that company's "control and supervision."

One of the more curious lawsuits came from a former captain of the ship. Ruslan Zaynigabdinov of Russia wanted some $122,000 US in unpaid back wages.

In a statement of defence filed in St. John's, the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. claimed Zaynigabdinov was fired for crashing the Lyubov Orlova into a dock in October 2009, then breaking into the vessel's safety box and destroying a computer.

These lawsuits were all either eventually discontinued on behalf of the plaintiffs, or deemed inactive by the court. CBC News was unable to discern whether any settlements were paid out.

When the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. abandoned its ship in St. John's Harbour in September 2010, it also abandoned the crew on board.

Many of the 51 Russians and Ukrainians working as seamen, housekeepers, galley cooks and officers had been living on the Lyubov Orlova for almost a year by that point and were not due to see the roughly $300,000 they were collectively owed until their contracts were finished.

That wouldn't happen until the ship reached Tenerife, the largest of Spain's Canary Islands, and it was becoming increasingly apparent it never would. So the crew sued as well.

Their claim was also reported to the UN's International Labour Organization, where it still sits, unresolved, in the agency's database of reported incidents of abandoned of seafarers. It's one of the largest such cases in terms of the number of people abandoned and the amount of money owed.

A brief email from the ship's captain to its owner in autumn 2010, included in court documents, hints at a chaotic atmosphere on board the ship in St. John's Harbour.

"Please be noted that the crew situation at the present time is very bad," he wrote.

"I try to keep control but in any case please arrange urgently to remove all alcohol store from the ship ASAP."

Alexander Pokhilets, captain of the Lyubov Orlova, and the crew's union representative, Gerard Bradbury, speak with CBC's Azzo Rezori on Dec. 10, 2010.

While the crew was free to come and go from the Lyubov Orlova, they had no place to live outside the ship and little to no money. Their visa to work in Canada was only valid for employment on board the ship.

Gerard Bradbury, an inspector with the International Transport Workers' Federation, acted as an advocate for the crew and filed a claim against the ship's owner on their behalf. In a 2015 blog post on the federation's website in which he looked back on the experience, he described the atmosphere on the ship as "hell."

"There was an officer with a heart condition," he wrote. "That was a bit of a panic … we also had to line up medical visits to the ship, get assurances that things were OK, figure out what we had to do for immediate needs. It's a lot of people, and they have nothing."

Svetlana Shabanova of Novorossiysk, Russia, says she never received any of the $3,844 she was owed for her work in the Lyubov Orlova's dining room that season.

She said the crew didn't have much, but never went hungry thanks to the generosity of St. John's residents, who donated food and drinking water through the Salvation Army and Red Cross.

Movies on the big screen in the ship's lounge became routine, she said. The crew liked to watch comedies — she called it an "anti-stress" measure.

"[It was] funny, like cinema," she said in an interview over Facebook Messenger. "With popcorn and Pepsi."

The ship's owner didn't completely ignore their plight. The Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. countersued the few who were able to get passage home, arguing their contract wasn't technically over until the ship reached the port of Tenerife. Any crew who left before then, the company said, were abandoning the ship.

At around the same time, the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. was busy looking for somebody willing to offer a mortgage for the ship.

The company secured a 470,000-euro mortgage in October 2010 from Sumena S.L., a ship supplier based in the Canary Islands.

Representatives from Sumena came forward about a year later with a claim to proceeds from the Lyubov Orlova's eventual court-ordered sale, saying they never saw a single mortgage payment.

The rest of the crew, after having spent some two to three months on the ship, returned home gradually that fall and winter, as cold weather set in and the vessel's diesel supply dwindled. Family stepped in to help some of them, while the Russian government bought flights for the rest.

Their lawsuit was also ultimately unresolved.

The Sea Queen

Left to the elements in St. John's Harbour that winter, the Lyubov Orlova deteriorated quickly.

Frigid temperatures burst pipes, creating a "dark" and "dank" atmosphere with "a disgusting smell of mould and rot throughout," according to a 2011 sheriff's assessment of the ship.

Rats seemed to like the conditions and moved in.

Dirty, chemical-laden water pooled in ballast tanks, causing the vessel to list awkwardly.

Canada's Federal Court hired Jacques Pierot Jr. and Sons Inc., an appraisal firm out of New York, to assess the Lyubov Orlova before its court-ordered sale in December 2011.

It concluded the cost of repairs would limit any potential as a "cruise, or even a hotel, ship or a floating casino," leaving it with a "negative value on an as-is/where-is basis."

"She will continue to represent a liability to all parties," the appraiser warned.

Despite the warning, Neptune International Shipping Co., based in the British Virgin Islands, bought the ship for $275,000 in a court-ordered sale. But the ship stayed in the harbour for another year.

Berthage fees continued to climb, spurring the port authority to launch a second lawsuit, this time against Neptune, in November 2012.

Two months later, a little tug called the Charlene Hunt, commissioned by Neptune, appeared in the harbour. It hooked up the Lyubov Orlova on Jan. 23, 2013, and started its tow south toward the Dominican Republic so it could be broken up and sold for scrap.

There is evidence that Neptune's owners had entertained the possibility, however briefly, that the ship had a future.

Emails between Transport Canada management and inspectors indicate the original plan was to fix it up and sail it out of St. John's under a new moniker, the Sea Queen.

"[One owner] said it was going to scrap and [the other] said they were taking it to 'humanitarian' purposes as a hotel in Haiti."

Nobody planned for what actually happened next.

Within a day at sea, the Charlene Hunt's towline broke, sending the Lyubov Orlova adrift.

Southeast International Maritime LLC had issued Neptune a certificate of insurance on the tow worth $850,000 US against a total loss of the ship.

The problem was, the insurance only became payable upon receipt of a $13,275 US premium, which account manager J. Kevin Lally said he never received.

"I've been in the business for 40 years and these are the strangest clients I have ever had," Lally said of the team at Neptune.

"They wouldn’t answer questions about the ship, wanted a quote, and the next thing I knew the ship was on the news."

CBC News tried to reach Neptune's owner, Hussein Humayuni, and Reza Shoeybi, who acted as a spokesperson for the company in 2013, but was unsuccessful.

At the time, Shoeybi insisted to the media and federal government that he was working to get the situation under control.

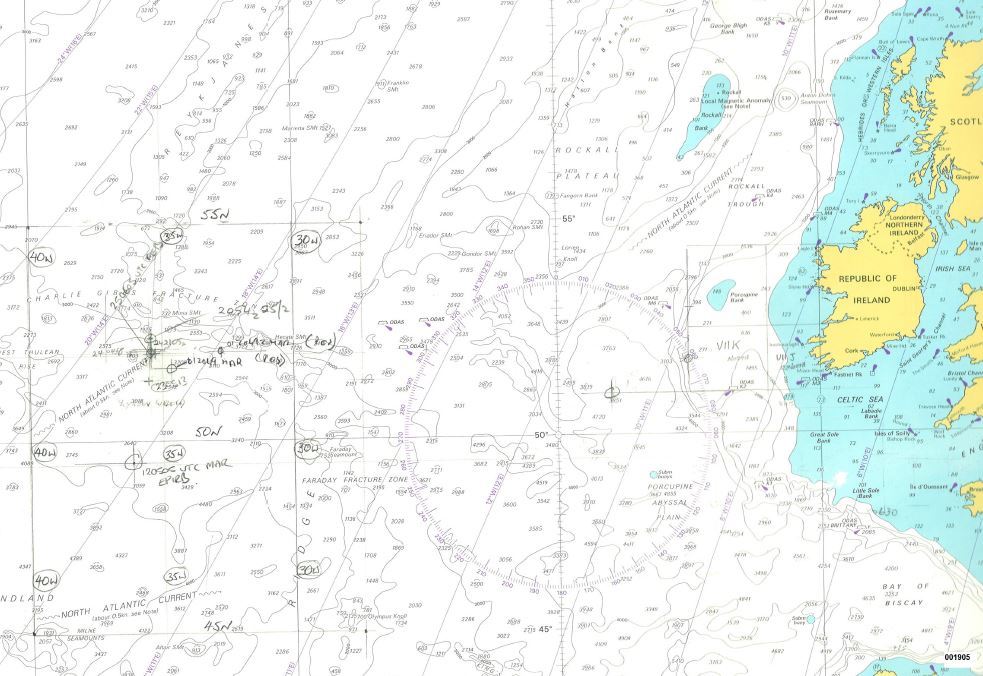

Things became more urgent as ocean currents carried the Lyubov Orlova closer and closer to the Hibernia oil platform, located 315 kilometres east-southeast off the coast of St. John's.

Transport Canada had to do something.

It hired a ship called the Maersk Challenger to attempt a second tow on Feb. 2, 2013, but the line broke within minutes in the rough Atlantic waves.

The Challenger crew determined a third tow attempt would be too dangerous. The Canadian government had always maintained the ship was ultimately the responsibility of its owner. And seeing as it was now in international waters, not carrying pollutants and no longer a threat to the Hibernia oil platform, the government let it drift away.

The decision angered the federal NDP's transportation critic, Olivia Chow, who at the time called Transport Canada "irresponsible" for letting the ship go.

"Transport Canada is really falling down on its job," she said. "It's important they make sure that these tugboats that are tugging these cruise ships … really have the capacity to do so."

Meanwhile, the Lyubov Orlova had been outfitted with a number of devices called emergency position-indicating radio beacons, or EPIRBs. They were stored in the ship's lifeboats and programmed to send a GPS signal once submerged.

One of the ship's EPIRBs went off on Feb. 23, 2013, followed by another on March 8.

Four days later, an email was sent to dozens of Transport Canada staff with a photo that may depict the very last vestige anybody will ever see of the vessel.

"A potential red herring, or simply a very interesting coincidence," the email says, describing an aerial photo of a damaged lifeboat floating in the sea.

The email notes similarities to the Lyubov Orlova's lifeboats, although it concludes there is "no conclusive data they are one and the same."

On April 26, a Maritime director for Transport Canada received an email from one of his staff confirming the Lyubov Orlova had not been spotted since March 8.

Today, the Lyubov Orlova is presumed sunk.

Considering the massive liabilities resulting from the Orlova's demise, there were surprisingly few consequences back in 2010 for abandoning a vessel in Canadian waters, like the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. had done in St. John's Harbour.

Under the Wrecked, Abandoned or Hazardous Vessels Act, passed earlier this year by the Trudeau government, the potential punishment for abandoning a vessel can lead to prison time and up to $1 million in penalties. It came into force on July 30, but Transport Canada has yet to lay any charges under the new law.

Even if it had been in effect in 2010, the Canadian government would likely have had difficulty holding the person who ultimately abandoned the Lyubov Orlova responsible.

That's because in order to do that, the government would have had to wade through the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co.'s convoluted offshore ownership structure to prove who that person was.

Who abandoned the Lyubov Orlova?

The story of the Lyubov Orlova revolves around two men named Oleg.

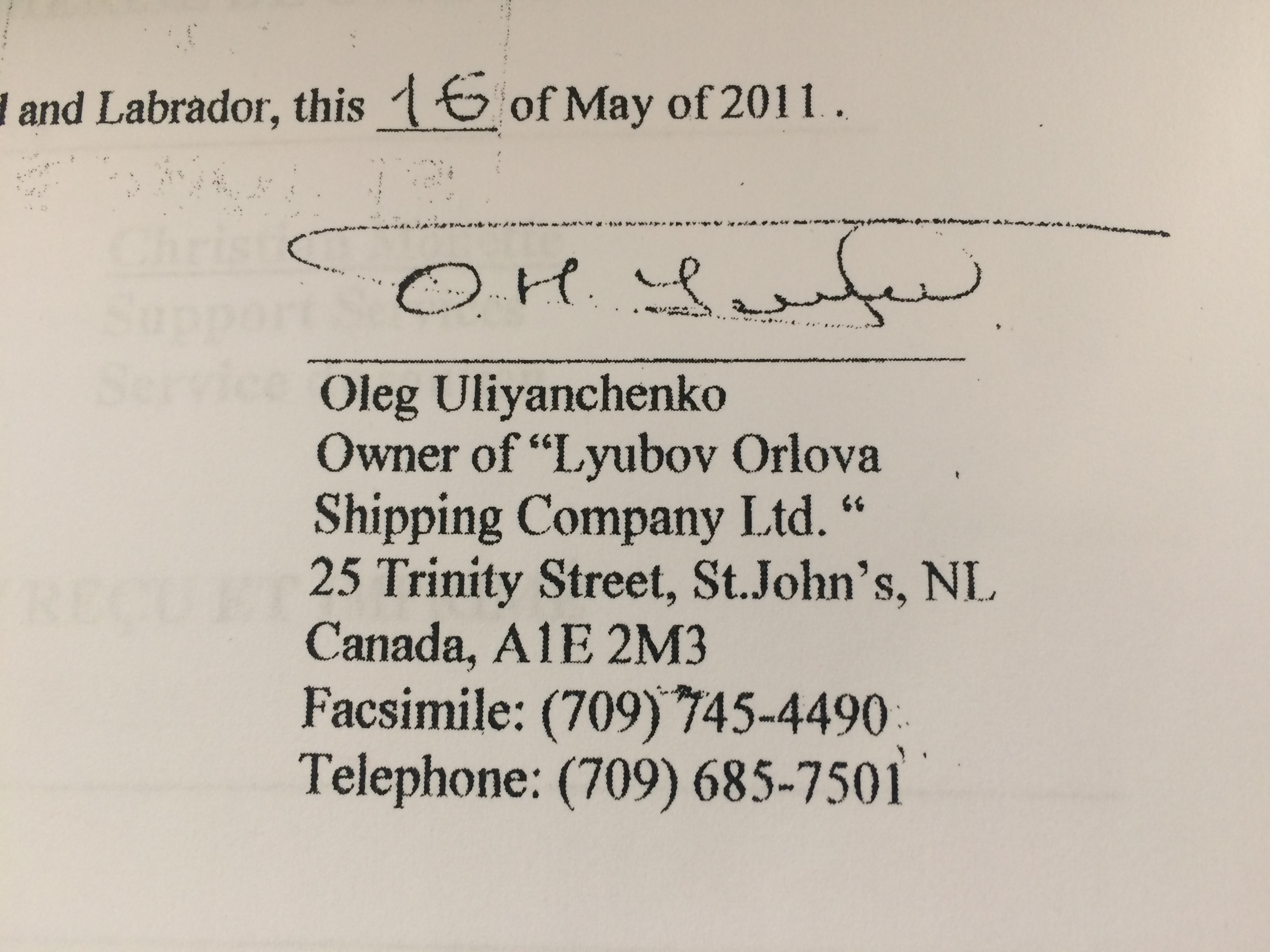

Oleg Uliyanchenko was a former officer with the Soviet Union’s anti-corruption police squad, the OBKhSS, according to a former ship's captain.

He bought the Lyubov Orlova from the Far Eastern Shipping Company in 1996 with Oleg Abramov, a former top manager for AvtoVAZ, the car company behind Russia’s famous Lada and Zhiguli automobiles. The two incorporated the Lubov Orlova Shipping Co. Ltd. in Malta that same year, and incorporated a similarly named Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. Ltd. in 2000.

At the time, Uliyanchenko and Abramov were alleged to have been smuggling AvtoVAZ automobiles that had been destined for a Middle Eastern car importer back into Russia for resale.

AvtoVAZ accused them of loading the cars onto a ship, sailing them out into the Black Sea, forging documents that allowed for their re-import, and selling the cars back in Novorossiysk.

In a quarterly financial report filed by AvtoVAZ in 2008, the company said it had taken civil action against the two Olegs in 2002, claiming 159 million rubles ($5.1 million US, calculated according to the 2002 exchange rate) in damages for the stolen cars. The documents state the company didn't expect to recoup that money because Abramov and Uliyanchenko had by then fled Russia.

The AvtoVAZ financial report also mentions a criminal case had been opened into the matter by the Investigative Committee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation.

The AvtoVAZ documents detail numerous complaints made to Russian prosecutors over "inaction" from their regional counterparts, resulting in the case being reopened and subsequently suspended several times between 2002 and 2008.

CBC News was unable to obtain the original Russian court files related to the civil or criminal cases against the two Olegs.

Stories similar to the allegations against Uliyanchenko and Abramov are a dime a dozen in Russia, says Matthew Light, a University of Toronto professor whose research focuses on post-Soviet law enforcement.

Corruption persists in post-Soviet Russia, he explained, because people who had power and influence under the Soviet system were able to maintain that power under free markets.

Anybody with connections with police or regulatory authorities, for example, essentially remain "untouchable," he said.

Uliyanchenko and Abramov originally used the Lyubov Orlova as a ferry service across the Black Sea, between Novorossiysk, on Russia’s southwestern tip, and Istanbul.

By 2000, the ship sailed out of Russia for good, under contract with a U.S. company, Quark Expeditions, for trips to Antarctica, and Canada-based Marine Expeditions for Arctic cruises.

The next year, the Lyubov Orlova made international headlines for the first time, after one of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co.'s owners allegedly held a group of cruise passengers hostage en route from Dartmouth, England, to Reykjavik, Iceland.

At the time, the New York Times reported that, according to passengers, Oleg Abramov remotely ordered the captain to turn the ship off course, toward Gibraltar, in order to shake down his mostly American and Canadian passengers for some $20,000 in docking fees he was owed.

The story details passenger accounts of clandestine calls via satellite phone to alert investors of the situation, and that "several" of them claimed to be the person who saved the day.

According to Dugald Wells, president of Marine Expeditions at the time, that's not quite how it went down.

He said Marine Expeditions was in default of its contract with the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., and Abramov did take the ship off course "or so we were informed, we [the investors and management team] were not on board of course."

But, Wells says, his team was aware of the situation via the captain, shipboard staff, and ship's owner, and were working to resolve it.

"No clandestine calls were required," he said.

Wells said the Marine Expeditions investor group paid the costs to repatriate the passengers, and all of their future bookings were refunded.

Abramov never faced any legal consequences for his actions, according to Wells.

In the following years, the Russian government's on-again-off-again AvtoVAZ embezzlement investigation, as referenced in the company's financial documents, continued to dog Uliyanchenko and Abramov. News outlets in Novorossiysk reported that the pair were put on an international wanted list in 2003, and even spent some time in international waters on the Lyubov Orlova to evade capture.

Interpol did arrest Abramov at a Monaco casino in 2004, according to reports in Russian media, but the local government refused his extradition. Later that year, Abramov sold his remaining shares in the ship to Uliyanchenko.

Uliyanchenko, in turn, transferred 499 shares of the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. to the Melinda Foundation, based in Panama. He retained a single share.

Panama: A great place to hide your money

The Melinda Foundation, majority owner of the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. when the ship was abandoned in St. John's Harbour, is essentially a financial instrument that, on paper, can own a corporation.

Very little public information is available about the Melinda Foundation. It was incorporated in November 2000, and its listed address is on the 16th floor of the Torre Swiss Bank tower in Panama City.

Panamanian foundations are designed to be clandestine, according to experts.

"Panama is not a country, it's a business," said Jeffrey Robinson, who has written 29 books about international financial crime.

"It's horrendously scandalous. But what are you gonna do? Tell Panama to stop?"

The Panamanian government keeps ownership of foundations secret. Even if the corporation the foundation owns is registered offshore from Panama — such as Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. — that foundation is completely impervious to any taxation or civil and criminal liability outside the country.

That's according to Lakshmi Kumar, a policy director at Global Financial Integrity, an organization that studies illicit financial trade. Over the course of her career, Kumar has studied Panamanian organizations specifically.

"The law, in very explicit terms, provides protection of the assets against any outside interference," she said.

The country makes its money from fees associated with the accounts, which are typically much cheaper than the taxes corporations and individuals would pay on their fortunes in their home countries, according to Kumar.

While Melinda Foundation was primary shareholder of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., Oleg Uliyanchenko seemed to play a central role in running the company. He was its legal representative, judicial representative and director.

His is the only name associated with the Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. in court documents. His signature appears most commonly as director of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., and in one instance, owner.

CBC News spoke to several former and current employees and management staff for charterers of the Lyubov Orlova and nobody definitively identified Uliyanchenko as sole owner of Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co., although they all said he was the one person they dealt with regarding the ship.

Who is Oleg Uliyanchenko?

It’s difficult to find much in the way of verifiable information about Uliyanchenko, 57.

Jason Whittle, a chef from Newfoundland who worked on the Lyubov Orlova for multiple cruise seasons, remembers him as a man who could speak some English and had an outsized presence.

"He was a big, big man. I would say 6-5 or 6-6," he said. "I remember once asking [a colleague], 'How did he make his money?' And he commented to me, 'That’s not something we want to know.'"

Uliyanchenko's name is associated with several financial endeavours around the world.

In Russia, he has owned a restaurant, fish processing plant, sea passenger transport businesses, car service centre and even a vulcanized rubber recycling plant.

In France, he started a seafood import business called Azov's Caviar in 2006, two years after he bought out Abramov.

According to financial statements, the amount of money the business took in remained very low until 2010, when it reported a 190,000-euro turnover.

The 2011 fiscal year, right after Uliyanchenko secured the 470,000-euro mortgage on the Lyubov Orlova, was an outlier for Azov's Caviar. It took in 200 per cent more money than it did the year prior — 582,573 euros.

In financial documents, that steep increase appears mostly as "crab sales." The company’s expenditures also increased, leaving a reported profit of 4,072 euros.

That year was an outlier for another reason — it also happened to be the last time Azov's Caviar would report any financial activity.

Uliyanchenko was last known to be living in the south of France.

He entered bankruptcy proceedings in France in December 2018.

All of his Russian businesses have also been liquidated. Both the Lubov Orlova Shipping Co. and Lyubov Orlova Shipping Co. have been struck from the Maltese registry. It’s impossible to tell the current status of the Melinda Foundation.

CBC News reached out to Uliyanchenko multiple times to request an interview about his involvement with the Lyubov Orlova. He replied once, in French, simply to confirm his email address.

The entire abyss

About 35 years ago, when the Lyubov Orlova was painted bright white and still considered a modern vessel, Soviet poet James Patterson stepped aboard.

A former child star, Patterson had developed a very close relationship with Orlova, the actress, while filming the 1936 Soviet classic, Circus.

He writes briefly about his visit to the Lyubov Orlova in his memoir, A Breath of Larch, mostly how it brought up memories of his life at sea in the navy, as well as memories of his old friend.

While on board, Patterson was inspired to write a poem about the ship.

At the time, he couldn’t have known how the Lyubov Orlova would meet its end, floating aimlessly in the north Atlantic before sinking to the cold, dark ocean floor.

But his poem reads almost like he did.

Вся пучина слабо пульсирует,

Состоянье ей это свойственно.

И казалось, гипнотизирует

Это кажущееся спокойствие.

Что нас ждет? Океанская звездность,

Что, как весь этот мир, стара?

На рассвете в подводный космос

Нам уже погрузиться пора.

The entire abyss weakly pulses,

A characteristic peculiar to it

This apparent calm seems to mesmerize

What awaits us?

A stellar expanse of ocean that is as old as all this world?

At dawn in underwater space

It is time for us to dive.