Sucdi Barre was excited to bond with her newborn — to feel his heartbeat next to hers during nursing and skin-to-skin contact.

But her plans were derailed after an emergency caesarean section ended with knife-like pains in her back, her chest so tight she couldn’t breath.

A nurse advised her to walk it off. But eventually her doctor ordered an electrocardiogram that showed Barre had suffered a massive heart attack. Doctors put a stent in her heart but it didn’t help.

“My heart vessels just started shredding. ‘They’re like, Yeah, you had another heart attack. You had another heart attack. This part of your heart is now gone,’” said Barre, 34, recalling how the birth of her son, Yonis, in August 2017 turned into a fight for her life.

“All the treatments that were in place that were in the literature that they tried — I was not responding to them.”

Her case left medical teams at two Edmonton-area hospitals perplexed. Four days on, she was transferred to the Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute.

The new mom was diagnosed with spontaneous coronary artery dissection, or SCAD. Blood vessels in her heart had suddenly separated, blocking blood flow and oxygen to the heart and triggering heart attacks.

According to Heart and Stroke Alberta, 90 percent of SCAD cases involve women between 30 and 60 years old. The underdiagnosed condition accounts for 25 per cent of all heart attacks in women under 60. In childbirth, the incident rate is less than 1 in 1,000 births.

A week after giving birth, Barre was in the intensive-care unit, on fentanyl and oxygen, tubes snaking out from her body.

She heard the voices of family and friends as she drifted out of consciousness, unable to move because of the pain. The beep of the heart monitor reassured her she was still alive.

Her heart was functioning at three per cent.

Two weeks later, doctors told Barre she would need an artificial heart device or she'd be dead within days.

Listen to Barre talk about those harrowing first few days.

“And they showed me how that looked, and I just broke down in tears. Because I'm like, 'How am I going to carry a baby and live life and be normal? I can't even walk to the bathroom. I have a five-pound machine on me,’” Barre recalled in an interview with CBC News.

But she realized it was her son's only chance to grow up with his mom.

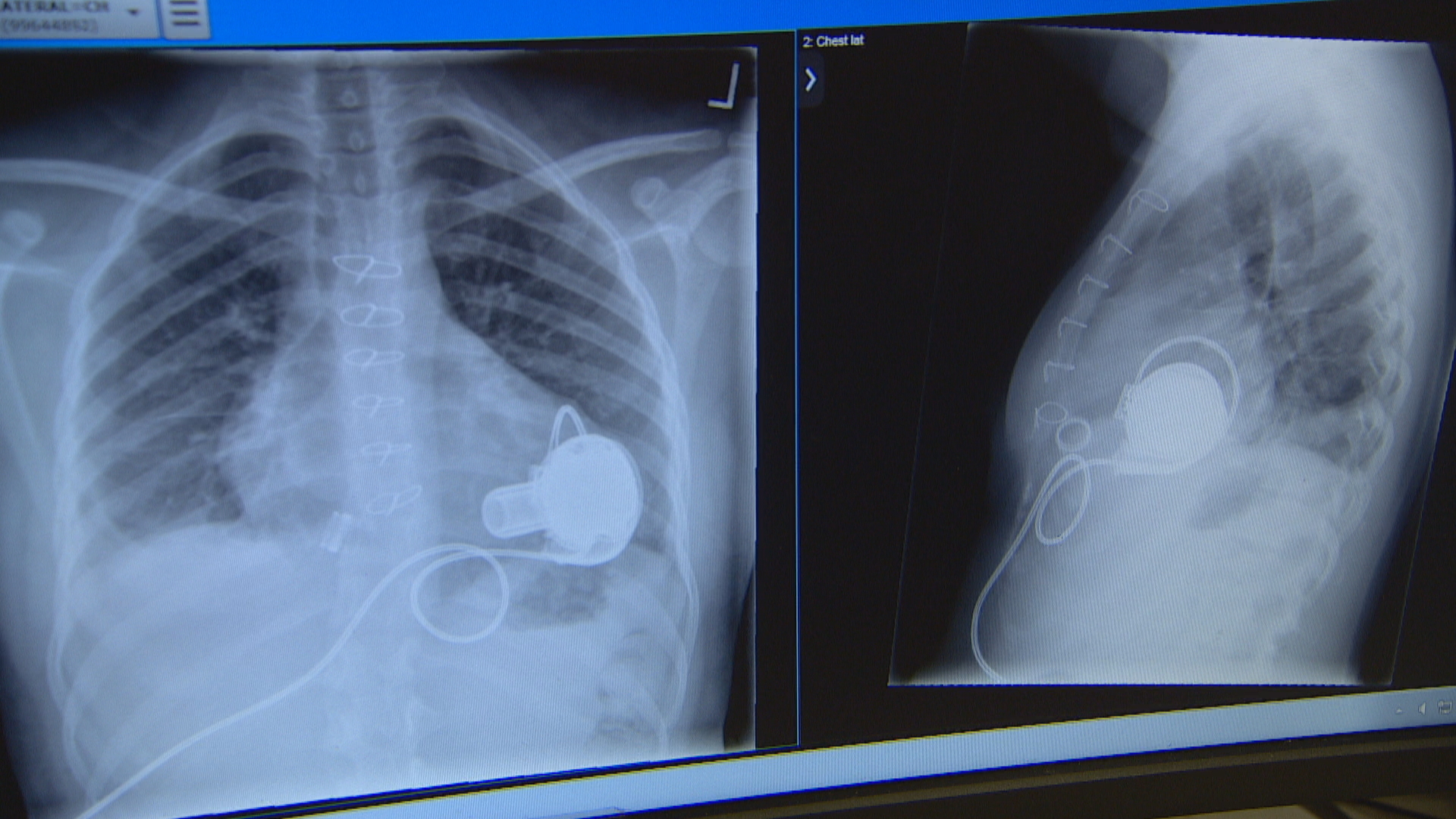

The left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, is basically an apple-sized device implanted into the heart that keeps the blood pumping. It’s operated by a small computer and two batteries worn around the waist.

Afterwards, Barre still couldn’t bond with her baby. The pain made chest contact impossible while painkillers ruled out breastfeeding. Instead, family placed the newborn on a pillow on her lap so Barre could look into her son’s eyes and feel his tiny hand gripping and releasing her finger.

“And that's how much bonding I got with my baby,” said Barre. “In my head, I'm a mom. But physically I couldn't do anything to take part in activities of caring for the baby.”

It was a baffling situation for Barre, a social worker and entrepreneur, who eats healthy, stays active and had read up on all the latest research prior to giving birth. She wondered if she could have done more to stay healthy.

But Barre’s cardiologist at the Mazankowski said there are no prior symptoms in SCAD patients who are otherwise typically healthy, young women.

“There are no warnings,” said Dr. Holger Buchholz, a professor of cardiac surgery and director of the artificial heart program. “There is nothing you can do when it happened to prevent it.”

In late November 2017, Barre was released from hospital. The simplest tasks required tremendous energy. She constantly feared she might die if she ate the wrong food, fell down, or her batteries died.

“There are many challenges that come with living with a mechanical heart device, but it really was a blessing,” said Barre. I was alive because of it.”

She hopes sharing her story helps raise awareness among the medical community and public about the underdiagnosed condition of SCAD.

“Because SCAD is rare, it may not be on the top of the list of differential diagnoses for many doctors,” say doctors with Heart & Stroke Alberta & NWT.

CEO Donna Hastings said educating the public and medical community is a priority for the foundation.

“We are working to ensure that all health professionals — EMS through emergency through birth settings — have an increased awareness of SCAD, so it can be recognized at the onset of symptoms, particularly in an emergent situation, because it really can be life and death,” said Hastings.

While the causes of SCAD are still being researched, possibilities include hormonal changes, systemic inflammation and genetics, said Hastings. It can be triggered by highly emotional events, such as the death of a loved one or physical stress, including intense workouts. Giving birth is at the top of the list.

In February 2018, Barre had a minor stroke and was told she needed a heart transplant. But because of her small size, blood type and antibodies from the pregnancy, she only had a five-per-cent chance of finding a match.

Instead her medical team, whom she calls her “living angels,” made an unexpected discovery. Her heart was operating at 40 per cent.

“To our surprise … her heart got stronger and stronger again and then went to a level that we thought, you know, there is a good chance that she maybe will be OK without the device and just with her own heart again,” said Buchholz.

At learning the news Barre rejoiced "... oh my God, I danced. I danced in my room in the hospital. I"m like 'oh my God I can't believe this is happening.' "

Watch Barre describe the joy of finding out she could remove the artificial heart!

In April 2018, the LVAD was decommissioned. Barre could finally run and cuddle with her son and scoop him up in her arms.

She has started a blog and YouTube channel to offer resources and hope to mothers facing similar challenges. She also became an organ donor.

Right now her heart is holding steady. But Barre knows the day may come when she needs to go back on the machine or, if chances of finding a match improve, have a heart transplant.

“We don't know how long it's going to last. But every day's a gift.”