"You didn’t say no."

"Maybe he just really liked you."

"You just feel guilty."

You don’t expect to hear those words from a police officer.

Not in 2019.

Not in a city where almost one-third of sexual assault complaints were deemed unfounded between 2010 and 2016, and where a shocked police service vowed to do better.

Not after a new victim-centred, trauma-informed sexual assault investigation policy was created.

And yet a woman who says she was sexually assaulted says that's what she heard from a London police constable in February 2019.

Dayna's Story

It took Dayna Hildebrandt almost a month to report her sexual assault.

She’d gone out with her friends for a night on the town at a popular downtown nightclub on January 12, 2019.

She had about 10 drinks, maybe more.

She was drunk.

Her acquaintance was the designated driver. She'd rebuffed his advances earlier.

He drove all her friends home first, then her.

He came inside.

They sat on the couch, and he rubbed her back. Then he kissed her.

Next thing she knows, she says, she’s upstairs and he’s on top of her, having sex.

She feels disgusting.

Hildebrandt says she didn’t say "no."

“I was really drunk and he took advantage of that,” Hildebrandt says.

She says she definitely did not say "yes."

It took a while to build up the courage to talk about what happened that night but about four weeks later, Hildebrandt walked into the London police station at 601 Dundas Street to report she’d been sexually assaulted.

Nervous but determined, Hildebrandt went in on a Tuesday night, Feb. 5. She brought a male friend with her for moral support.

The wait to speak to an officer would be five to seven hours, she was told.

“I thought you could just go in and speak to an officer right away. I expected compassion but I got the opposite,” she says.

Although officers are in police headquarters at all times, someone has to be called off the street to take a walk-in report, says London police Chief Steve Williams.

“Sometimes there is a significant wait time,” Williams admits.

“Speaking specifically to sexual assault, we understand it takes courage and bravery, no doubt, to come in and make a disclosure like that to a stranger in a police station. We would expect that person to be dealt with with sensitivity and dignity.”

And yet, Hildebrandt says that's far from what happened in this case.

A visit from a constable

Hildebrandt's complaint was logged in the computer system as an assault. Not a sexual assault, according to police documents.

Why that happened is not clear, but a sexual assault should be coded as such, Williams says.

A constable arrived at Hildebrandt’s apartment just after 7 a.m. the following day, Feb. 6. She was a little taken aback at the early hour.

Right away, Hildebrandt says, she felt dismissed.

“I felt like I was wasting his time. Like he didn’t want to be there. He had no interest in hearing what I had to say.”

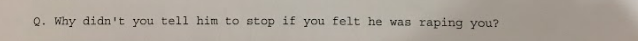

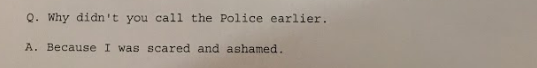

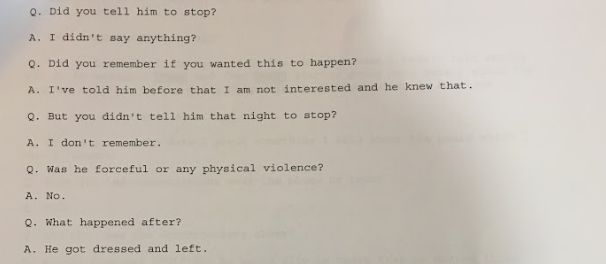

After Hildebrandt tells the officer what happens, he asks her follow up questions.

The things he says take her aback.

“I have never felt more unsure of myself in my life. I started to doubt right from wrong, I doubted everything I ever believed in. That day was a really dark day for me. After I went through everything, I wanted to kill myself.”

Hildebrandt still gets emotional thinking about that interaction with the constable. Her hands shake. Tears well in her eyes.

“It felt like something out of a movie. He told me that I should take more responsibility for my actions while I’m drinking. He said that this happens all the time, this is how families start, and that it happened because he probably just liked me.”

Dayna recounts the constable's words

The officer leaves.

He tells her he’ll contact the sexual assault section to see if he should launch an investigation. He tells her it could be a few days, maybe a week, before she hears back from him.

At some point, the officer speaks to the man Hildebrandt has reported. We don’t know what he said. Those parts are redacted in the report provided to her.

Half an hour later, the constable calls back.

He tells her it wasn’t a sexual assault.

There will be no further investigation. There's not enough evidence to proceed, according to the police occurrence log.

“Honestly, he called me back so quickly that I thought he made up the part about calling the sexual assault people,” Hildebrandt says.

The officer’s notes, which Hildebrandt obtained by filing a freedom of information request, indicate he did contact a detective from the sexual assault unit.

The detective, recalling the events on June 20, after the freedom of information request is filed, writes, “During my shift I received a phone call from (the constable) regarding a sexual assault he was investigating. (He) advised me that he did not have grounds to lay a charge of sexual assault and did not feel that a sexual even took place.”

She told the constable to forward the call “as an FYI” to the sexual assault section.

Four hours and 12 minutes after he is called to Hildebrandt’s apartment, the constable moves onto his next call.

He concludes:

“This was not a sexual assault. (She) got drunk, had sex, and then for some reason felt guilty and was influenced by friends to make her feel like a victim. As a result she called the police.”

“This was not a sexual assault. (She) got drunk, had sex, and then for some reason felt guilty and was influenced by friends to make her feel like a victim.”

The next day, another detective with the sexual assault section reviews the file, according to the freedom of information documents.

She writes, “No further action taken - it appears the victim was satisfied with Police involvement.”

Not so, says Hildebrandt.

Far from it.

“I’m not ashamed of what happened. I am angry at times but mostly I’m frustrated.

"We’re still teaching women to take better precautions instead of teaching men not to rape. Why is it my fault for going out and having a good time with my friends but it’s not his fault for taking advantage of me like that?

“Most people would agree it’s not my fault, but that day, when I dealt with London police, it was backwards. It was my fault. And I know they’re wrong.”

The police response

The day after CBC News contacted London police for comment about this story, one of the top officers contacted Hildebrandt.

Inspector Kelly O’Callaghan, who heads the office which investigates complaints against police officers, called Hildebrandt and told her the chief wanted her to know she can file a complaint against the officer.

Hildebrandt did so that night. The complaint is being reviewed by the Office of the Independent Police Review Director.

“When I learned about this incident, I was concerned enough that I had a member of our professional standards branch reach out directly to her the same morning and advise her how to make a report," said Williams in his office at police headquarters.

He's been in the top job since June.

"I take it very seriously and I hope the investigation is completed swiftly and we’ll determine further actions once that is complete.”

Hildebrandt making that complaint, however, also means the chief won’t answer any specific questions about her case, because her complaint is now under investigation.

London police officers are governed by a sexual assault investigation policy put in place in January.

It was developed by the London Police Services Board after a Globe and Mail investigation found almost one in three reports of sexual assault in London were deemed “unfounded.”

The policy directs the chief of police to “develop and maintain trauma informed and victim/survivor centred procedures for undertaking and managing investigations into sexual assaults.”

That includes everything from dispatching an officer, the initial response, how to investigate and how to help survivors.

Chief Steve Williams explains how sexual assaults should be handled

The policy also calls for ongoing training about sexual violence, consent, gender-based violence, privilege, power, trauma-informed approaches to investigations and gender bias and rape myths.

Williams says those procedures have been developed and the training has been done.

But the chief doesn’t know if the officer would have had the training when he responded to Hildebrandt, just a month after the police went into effect.

Sexual assault investigations, including the initial response by constables, should be done to ensure the victim feels dignity and compassion, Williams said.

But Williams can’t give details about the procedures because them could “harm the service’s ability to investigate crime,” a spokesperson says.

CBC News has filed a Freedom of Information request for the procedures and training given to officers.

'I'm beyond mad. It hurts'

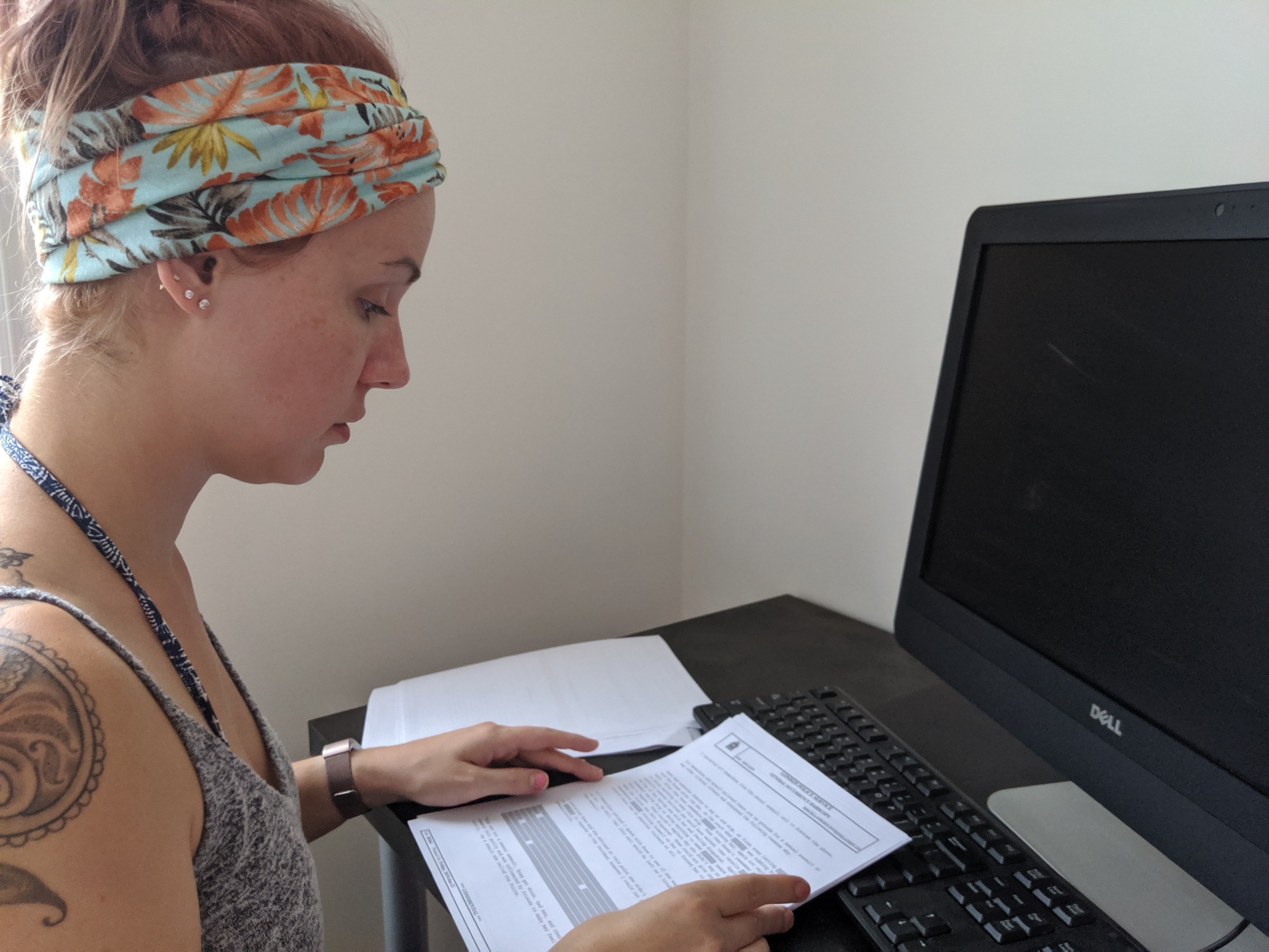

Three months after filing a freedom of information request to see the constable's notes, Hildebrandt gets a letter from the London police, asking her to come pick up the file.

She gets the occurrence report, which details her address and other information. The general information lists her case type as "assault." She agreed to let the man she is accusing of sexual assault know she is filing the freedom of information request. Any information mentioning him is redacted.

The officer uses her married surname throughout, even though she asked him to use "Hildebrandt," her maiden name. She is divorced.

Reading his notes in a coffee shop, her hands shake with anger.

"I don't want other women to just stay quiet."

"I'm so beyond mad. It's beyond upsetting. It's hurtful. This is why women just stay quiet and do nothing."

The paperwork, Hildebrandt says, confirms what she thought all along. That the constable wasn't interested in helping her. That he walked into her apartment not believing her.

But she's working with a therapist, and she doesn't want her story to dissuade other women from coming forward to report their own sexual assaults.

"I don't want other women to just stay quiet. I want them to know that they're not alone, that I'm listening, that a lot of people are listening," she says.

"I really thought things were different, that people were starting to listen to women, and for such a young man (the constable) to treat me this way, it was unreal. I don't accept it."