November 23, 2021

In a small prison boardroom about 800 kilometres from the site of the deadly Humboldt Broncos bus crash, the man responsible for the collision is making a case not to be deported.

"I just want one chance I can give back to the community and show that I'm not a bad person, bad human being — I'm just like everybody," said Jaskirat Singh Sidhu during a recent CBC interview via Zoom from the minimum security side of the Bowden Institution in Innisfail, Alta.

Except he's not like everybody.

While most drivers have at some point glanced down at their phones, tried to comfort a crying child or whining pet or felt hypnotized by an unending highway, their distraction likely wasn't fatal. Sidhu, on the other hand, will always be known for his deadly mistake on April 6, 2018: paying more attention to a tarp flapping behind him than the highway ahead of him.

He was eventually charged with 16 counts of dangerous driving causing death and 13 counts of dangerous driving causing bodily harm — and he pleaded guilty to all of them. He did not ask for a plea deal or appeal his eight-year sentence, which is the longest ever given in Canadian history for dangerous driving that didn't involve alcohol, drugs or purposeful misbehaviour.

That Sidhu’s actions caused the crash was never in dispute. But he’s subject to deportation to India once he’s served his time.

Sidhu's lawyers won't let him talk about what happened on that fateful day, because he's named in a number of civil lawsuits. However, court documents fill in some of the gaps.

After only a week of training and two weeks of supervision, Sidhu was on his second solo long-haul semi truck trip, pulling a load of peat moss on a double-trailer, driving on unfamiliar rural roads across Saskatchewan. Earlier that day, he had gotten stuck in the snow and needed a tow, which slowed him down.

When he finally got his shipment loaded and started driving back to Calgary, a protective tarp came loose and started flapping around. Fearing he would lose his load, Sidhu repeatedly checked his rear view-mirror, apparently missing signs warning of the approaching stop sign.

The court's agreed statement of facts found neither road conditions, the sun nor trees interfered with Sidhu's ability to see the intersection. Travelling an estimated 86 to 96 kilometres an hour, he blew through an oversized stop sign with a flashing yellow light.

At the same time, the team bus for the Humboldt Broncos hockey team was headed toward that intersection. It had the right-of-way, and driver Glen Doerksen couldn't stop in time. The bus hit the back of the semi, leaving a horrific scene that still causes Sidhu to wake up in a cold sweat.

"I can see the dead bodies, I can see the people crying, I can see the kids crying. I can see the first responders there, I can see myself standing there alone in the cold," the 33-year-old said. "I can see the devastation that was caused by me."

WATCH | Jaskirat Singh Sidhu apologizes for causing the 2018 crash in Humboldt, Sask.:

That Sidhu's actions caused the crash was never in dispute. But the reason he is now doing select interviews from prison is because, as a permanent resident convicted of a serious crime, he's subject to deportation to India once he's served his time.

Earlier this year, his lawyer submitted a 415-page binder of support for Sidhu to the Canada Border Services Agency officer responsible for this case. Recently, CBSA gave him until the end of November to present any final arguments.

That means the decision could be imminent.

Deportation is something Sidhu, despite all that has happened, would like to avoid. But among the families of the people he killed, the feelings are more complex.

Sidhu has just one opportunity to plead his case — and that is now, as a CBSA officer writes a report that assesses his eligibility to stay in Canada.

In the binder of documents sent to CBSA, Michael Greene, Sidhu's Calgary-based immigration lawyer, included correctional and psychological reports, letters of support from at least three Humboldt Broncos families, certificates of courses Sidhu has taken while incarcerated and job offers from various employers. The deadline for submissions is Nov. 28.

The CBSA officer will make his recommendation and send his report to a second officer (a Minister's Delegate) who will determine whether Sidhu should be referred to the Immigration Refugee Board (IRB) for an admissibility hearing — or if his personal circumstances merit an exemption.

If no exemption is given, in the vast majority of cases like this, the IRB orders deportation. The immigration minister can intervene, but that is rare. There is an opportunity to ask the federal court for a judicial review of any deportation order, but only on the grounds that due process was not followed — and that would only restart the admissibility process.

If Sidhu is ultimately deported, he could still apply to return to Canada under humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

"He has, on paper, what would sound like a good case, because he doesn't have a criminal history. This was one incident that was clearly not premeditated. He's extremely remorseful. There's no sign that he's a risk to re-offend in any way whatsoever," Greene said.

"He's not a risk to the Canadian public. He's never going to get in a truck again. He's probably never going to drive again," Greene said, adding that part of Sidhu's sentence is a 10-year ban on driving. "He's not somebody that we need to be afraid of."

"He wants to be here. He wants to make up for what he did, and do something positive.”

In some ways, Greene said remaining in Canada would be more difficult for Sidhu than "the anonymity of disappearing into the billion people that is India. Here, he's a household name and he's going to be recognized. He's going to have to live with that recognition all of his life.

"But he wants to be here. He wants to make up for what he did, and do something positive."

Sidhu came to Canada from India as an economic immigrant in 2014 with a degree in commerce and a head full of dreams. He was following his then-girlfriend and now-wife, Tanvir Mann, who had a nursing degree from India.

In Canada, Sidhu got his diploma in business administration while Mann upgraded to become a critical care nurse. She had been accepted into the Toronto College of Dental Hygiene, so she and Sidhu were working customer-service jobs to afford the tuition.

The couple was married in India just three months before the crash.

After they returned home from the ceremony, Sidhu took a job as a semi driver with a small Calgary trucking company after a friend suggested it was a better way to earn money.

After a one-week training course and two weeks of supervised driving, Sidhu was on his own. The load he was hauling on April 6, 2018, was one of his first solo jobs, and the first in rural Saskatchewan.

"I never wanted him to do this, because [trucking]'s one of the most difficult jobs out there," Mann recently told CBC in an interview from their small apartment in Calgary.

She recalled waiting for hours to hear from him on the night of the crash. Her phone calls were not returned. Finally, Sidhu called her around midnight.

"He told me he made a big mistake," Mann said emotionally, pausing to regain her composure. "I turn on my laptop and [saw on the news sites] it was a disaster and I just couldn't believe it happened. … I could see, you know, the damage. The crash site. Families that lost so much."

About a year later, Mann was in the courtroom to hear her husband plead guilty to an unimaginable crime. She was there during four days of emotional and heart-wrenching victim impact statements. And she was there when Sidhu was sentenced and sent to prison.

Mann is a private person. Mindful of not wanting to upset the Broncos families, she agonized about doing media interviews. But she felt she had to.

"I am speaking out today on my husband's behalf so I could tell everyone he is a very simple and generous man who should be given a chance to stay in Canada because he did not intend to hurt anyone," she said.

WATCH | Sidhu’s wife, Tanvir Mann, describes the night that changed their lives:

Mann is also a permanent resident but waiting for her oath ceremony to become a Canadian citizen. That was supposed to happen in August, but was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because her life and education is now on hold, she said Sidhu wants to stay in Canada for her. But if he is deported to India, she said she will follow him.

"He's fighting his deportation because I am involved with him. If he was alone, he would have gone back, but now it's my career, my future and my future life, so he's doing it for me."

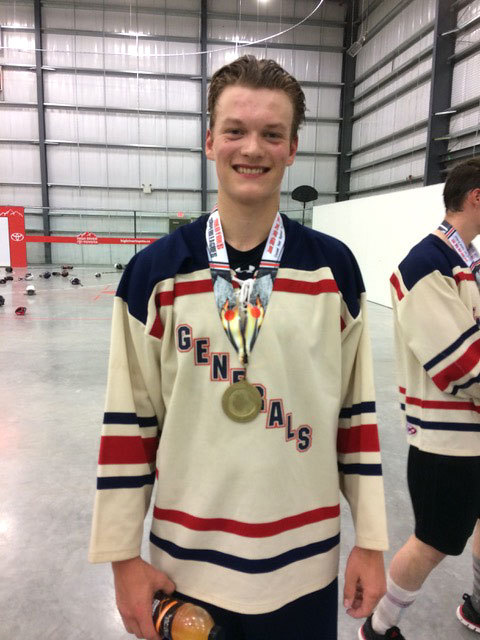

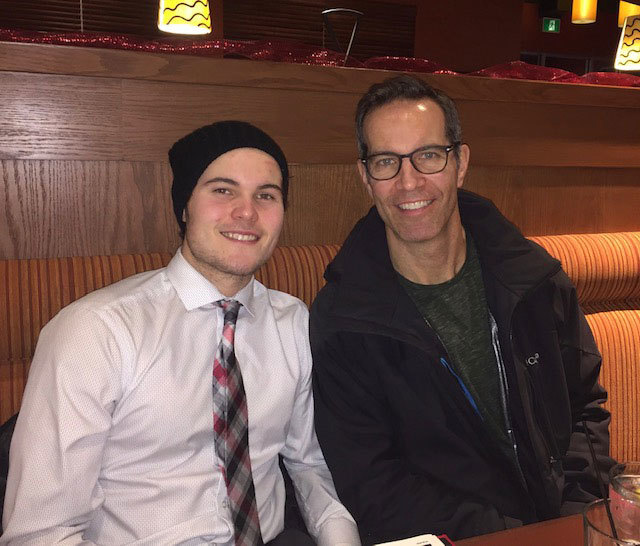

Scott Thomas thinks about the future a lot while coaching minor hockey in Saskatoon. Staying close to the game is a way of feeling close to his 18-year-old son, Evan, who died in the crash.

"I know he's here with me and I can feel his energy," Thomas said.

Reminders of his son are everywhere. His jersey number, 9, has been retired and has a place of honour in the Rodd Hamm Arena. Thomas's team, the Saskatoon U18 AAA Blazers, have stickers with Evan's initials on their helmets.

"I think we're a long way from healing," Thomas said, rubbing his arm, his eyes welling with tears. But as part of their healing journey, Thomas and his wife, Laurie, met with Sidhu during the court hearing in 2019 to tell him they forgive him.

"I think empathy and compassion go a long way," Thomas said. And while that's not always easy, he believes it's what Evan would want them to do. It's why the family has also written a letter to the CBSA, supporting Sidhu's bid to stay in Canada.

"There were a lot of extenuating circumstances in this case. And yeah, Mr. Sidhu was ultimately responsible for how he operated in that vehicle, but there were so many other factors that went into that. His clearly inadequate training that allowed him to get behind the wheel of that vehicle, his lack of experience, he'd never been in that part of the world before — he basically was thrown to the wolves that day," Thomas said.

"While the result of his actions were violent and criminal, this wasn't by nature a violent crime. He didn't set out with the intent to cause harm. It was just a horrible, tragic accident. And it's our opinion that deportation doesn't need to be the necessary end to this."

Not surprisingly, other Broncos families disagree. They don't think Sidhu should be given a second chance — because their loved ones didn't get one.

"I feel this isn't even a battle we should be sitting here discussing right now. It should be pretty cut and dried when it comes to deportation," said Shauna Nordstrom, whose son, Logan Hunter, died in the collision.

It's a November day in St. Albert, just north of Edmonton, and Nordstrom and Andrea Joseph, another grieving mother, are leaning on the wooden sides of the Larose Park outdoor rink in their neighborhood.

This place has a lot of meaning for both of them. Logan Hunter, 18, and Jaxon Joseph, 20, were part of a tight-knit hockey community here. Both spent hours playing shinny at this outdoor rink.

When the City of St. Albert asked the families of the four local victims where to put park benches to honour them, it was an easy decision for Nordstrom: the rink. "Because of the thousands and thousands of hours that [Logan] spent here."

She recalled that the first flakes of snow every season would mean it was close to the time for him to get back on the ice. "He looked forward to it, like, every year. He couldn't get enough."

Jaxon's bench is in a dog park, a short walk away.

"He always loved to go down there by himself to take our dogs down for a walk and we would go for bike rides down there. Picnics, fly the kite — it was a family place for us," Joseph said.

"Often I'll go to Jaxon's bench when I'm having a hard day, which are more often than few, and I feel peace," she said, touching a necklace with Jaxon's thumbprint engraved on a silver heart pendant.

Nordstrom and Joseph spend a lot of time here, remembering their boys. But it's bittersweet.

"A lot of times people think that time makes the pain go away. It's been three and a half years, 365 days. You add those days up … having tears for [more than] 1,200 days straight. It's hard," Joseph said. "[I] don't wish that on anybody."

The two mothers are speaking out because of promises they made to fight for justice — in Joseph's case, as she said goodbye to her son in the morgue. They say Sidhu made many mistakes before running the stop sign on that day in 2018, some of which came out in the criminal case, while others are being revealed in ongoing civil litigation.

Nordstrom still has many questions she'd like Sidhu to answer, starting with why he missed four warnings that a stop sign was coming — and how he could possibly miss the oversized stop sign with the blinking light.

"Why did you run five stops? Why did you decide as an inexperienced truck driver that it was OK to get behind the wheel carrying all that ton of weight and not think about looking around and making sure you were extra alert when you don't know the roads and you're not familiar with what's ahead of you? Why were you looking behind, not front? How and why did this ever happen?"

Joseph said she will never call this an accident because it could and should have been prevented. She cited violations of federal and provincial trucking regulations that took place in the 11 days leading to the tragedy.

For example, court heard that Sidhu failed to account for time on and off the job, to account for the city or province where he spent each shift and to document whether the vehicle had any defects. For days such as March 30 and 31, 2018, entries in the driver's log book are completely missing.

If someone had inspected his log book before taking this trip, Sidhu would have been suspended, Joseph said.

"If he had been pulled over before the collision occurred, he would have been on a 72-hour stay because of his log book, his 70 violations in his log book that they discovered after, which he tried to grab from his truck."

WATCH |2 grieving mothers on why they think Sidhu should be deported:

Both Joseph and Nordstrom believe Sidhu should accept all of the consequences of his actions — including deportation. They say it's not like he's returning to a life of hardship.

"He has a wealthy family at home with a big farm. He's not going home to nothing. … He has a future there. To have him stay here and trigger constant PTSD for us...," Joseph said, pausing to collect herself.

Joseph said she wouldn't be able to bear it if one day in the future, she or a family member pulled up next to Sidhu and his wife, and their potential children, at an intersection in Calgary. She and Nordstrom both tear up when describing how their own sons always wanted children, and how that will never happen now.

"We miss our boys. We miss their smiles. We miss their laugh. We miss their hugs," Joseph said, turning to put an arm around Nordstrom as she started to weep. "We want justice and we want the truth to come out."

"I miss him. My baby, my only son," Nordstrom sobbed.

"Sidhu, he's not feeling the pain that we're feeling — oh, he's not feeling this pain," Joseph said. "Constant trauma. No peace."

It's coming to the end of the allotted time for Sidhu's Zoom interview from prison. He has to get back to his job packing groceries for inmates living in the minimum-security section of the institution.

But before he goes, he reaches into his jacket pocket and pulls out a handful of letters sent to him by Canadians with messages of support and encouragement.

"I read every single one of them and they're so gracious," Sidhu said. But while he gets some comfort from them, he, too, has no peace. He hasn't forgiven himself and doesn't know if he ever will.

"It's with me for my whole life."

"How can you forgive yourself, because you've caused this much pain to everybody?" he asked rhetorically. "A day doesn't go by without thinking about the accident, without thinking about the families. I pray for them."

Throughout the conversation, he repeatedly said sorry.

"I apologize, apologize to every single Canadian, I apologize to every single [person] in this country. Apologize to all the family members that I have hurt. I have given them so much pain," he said.

But Sidhu said running away and hiding is not a solution, because he can't run from his thoughts.

"I can't hide from my own soul. So it's with me for my whole life."