November 13, 2021

Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. This story is part of a CBC News initiative entitled Our Changing Planet to show and explain the effects of climate change and what is being done about it.

To understand how climate change will affect the most vulnerable in the population, visit Lake Charles, La., a city of 80,000 that hugs the U.S. Gulf Coast.

Two years of extreme weather unlike anything life-long locals have ever seen have decimated neighbourhoods, destroyed infrastructure and displaced tens of thousands of residents.

But Lake Charles is far from unique. It's part of a growing list of communities around the world that carry a devastating burden — a landscape that’s vulnerable to extreme weather, a social fabric beset with poverty and infrastructure crumbling from age.

- Have questions about COP26 or climate science, policy or politics? Email us: ask@cbc.ca. Your input helps inform our coverage.

A research study from the University of Southern California predicted that 13 million people living in coastal areas in the U.S. could be forced to relocate by 2100 because of flooding.

The ravages of climate change aren't on the horizon for Lake Charles — they’re here, and in plain sight, along with who suffers most.

"I always say that natural disasters don't discriminate, but recovery always does," said Tasha Guidry, a community organizer, business owner and 42-year resident of Lake Charles.

In 2020, Lake Charles was hit with back-to-back storms — hurricanes Laura and Delta had peak winds above 200 km/h.

That year was also one of the costliest and most active Atlantic hurricane seasons on record. But it didn't end there. An ice storm hit the city the following February, then an intense rainstorm. In October, a tornado ripped through neighbourhoods.

One disaster after another has turned Lake Charles into a city of blue tarps and red tags. The tarps cover roofs that are still not repaired. The red tags condemn some houses and buildings that will never be repaired. The mayor of Lake Charles, Nic Hunter, said 300 to 400 commercial buildings damaged in Hurricane Laura are being condemned or marked for demolition.

Guidry is quick to point out which part of Lake Charles has been left behind.

"Every time we're hit with the storm, it's always our areas that are hit the hardest and we're the ones with the least amount of relief, you know, monetary or financial relief in order to rebuild," she said, referring to the parts of Lake Charles that are mostly poor, Black and Latino.

"We don't have the hope anymore that we used to, and it makes it hard for us ... to rebuild and reinvest in our community because it seems as if nobody else cares."

It’s exactly how Bridgette Reed feels. She’s in public housing. Her house is unlivable, full of mould and leaks. But she stays there because she has nowhere to go. Adding to her burden, she has cancer.

"I've called the mayor. I've called Baton Rouge [the state capital], the governor. I’ve been making a lot of calls. No one will help me," she said, out of breath as she sat on a mattress in her home.

Guidry said Reed is just one of many heartbreaking stories in her city.

Looking at an empty field next to a cemetery, anyone driving by could be forgiven for assuming that the space was always empty. But Guidry knows better. The real graveyard is beneath her feet, where a row of Black-owned businesses once stood. The hurricanes reduced them to gravel before clearing them out.

"Most of them were either underinsured or the damage was too extensive for them to ... be able to rebuild," said Guidry.

In the richer business district of the city, however, where businesses have reopened and power lines are repaired, some are even hiring again.

"What you'll see in North Lake Charles, it's almost like a forgotten land, whereas in South Lake Charles, businesses are thriving," Guidry said.

Deacon Erroll Deville can confirm that. He's lived in Lake Charles for 71 years and witnessed the storms get stronger and come more frequently.

In his role as a parish leader, he understands more than most who gets left behind.

"All these poor people, all these poor people who can't afford to move," said Deville, who worries for his parish.

"This parish will die, you know, the city is not going to die, but it's going to go into decline. And I hate to see that, but there's nothing we can do about it unless things change in Washington."

Change in Washington is as complicated as Louisiana’s history with environmental justice.

So far, Louisiana has been granted $596 million in federal disaster relief. Louisiana’s governor, John Bel Edwards, estimates the full extent of damages from the last two years to be closer to $3 billion.

There's also a government program to buy people out of homes that are prone to flooding. The state of Louisiana announced $30 million to fund buyouts of low-lying neighbourhoods on the heels of 2020's hurricanes.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, has approved millions of dollars in grant money for individuals and parishes that cover everything from demolitions to temporary housing costs.

In the first days of his presidency, President Joe Biden signed an executive order that created the Justice40 initiative. The program aims to deliver 40 per cent of federal investments related to tackling the climate crisis to disadvantaged communities.

Beverly Wright, a professor and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, based in New Orleans, has devoted her career to environmental justice.

Her work has focused on advocating for communities affected by the pollution of petrochemical plants in her state. The industry still has a strong foothold in Louisiana, where a stretch of the Mississippi River has been dubbed Cancer Alley for its high rates of cancer linked to the pollution.

She's been appointed as an environmental justice adviser by the White House and is hopeful about Justice40 and the other funding programs coming to her state.

"The good news is the Justice 40 Bill, with all of this money that will be coming down the pipe, you know, this is a chance," she said.

"For the first time, large amounts of money will be going towards reducing air pollution, going towards infrastructure, building infrastructure for workforce development, things that directly affect poor communities, Black communities, minority communities."

But Wright is also realistic about the poor track record of politicians when it comes to protecting the vulnerable against environmental harms.

"They always were African American, Native American, Latino American, Asian Pacific Islanders, what I call despised minorities. So wherever you were, if you were the despised minority, all the bad stuff was placed there," she said, referring to polluting industries of oil and gas.

She sees the same things happening with climate change policy — she says minority communities, living below the poverty line, suffer most when governments don’t step up to address the problem.

"They respond to maintain the status quo, however it is. And they play to the people who don't believe that there's climate change," she said.

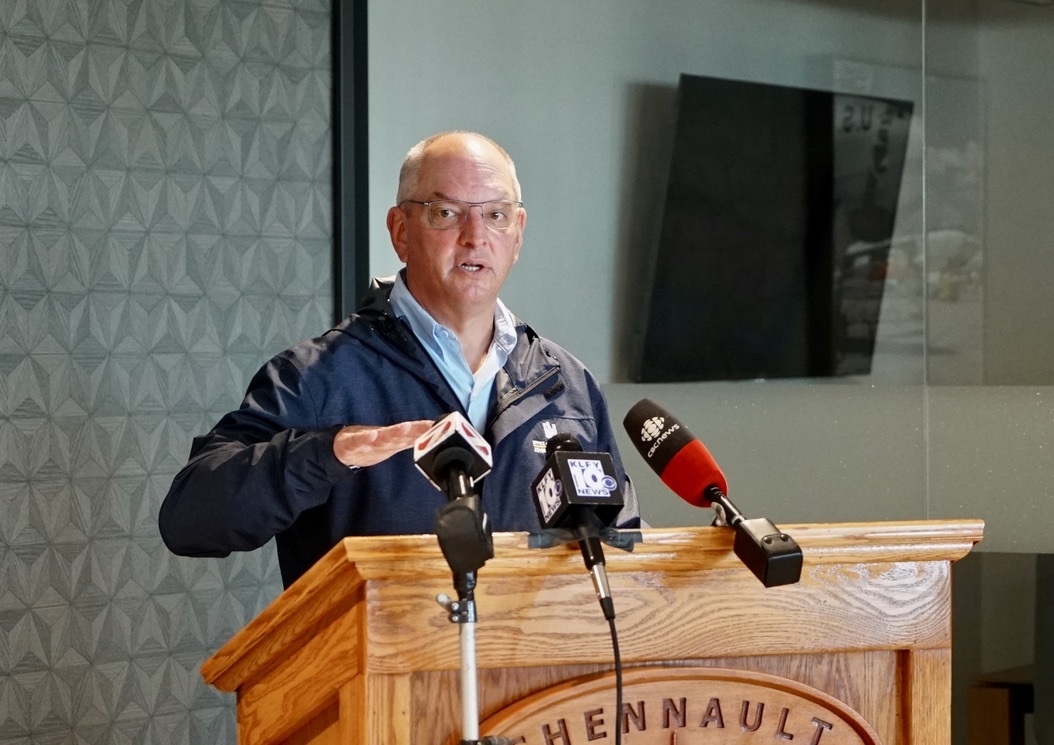

On the day that Edwards was leaving for Glasgow to attend the United Nations climate summit, COP26, he held a media conference in Lake Charles. We asked him what he planned to tell the world about cities like Lake Charles and people like Bridgette Reed.

"We're doing everything that we can to secure the funding necessary to effect a robust recovery. And we're doing it for people with unmet need," Edwards said. "That's why I went to Washington, D.C., five times. The $596 million is a good start. But it is just a start."

Edwards hopes to convince world leaders to come to Louisiana and invest in the state’s transition to cleaner energy.

"There's not another state in the nation that's more affected by this than Louisiana," said Edwards.

"There is no doubt in my mind that the weather events we're seeing here in Louisiana, across the country and across the world are becoming more severe and more frequent. I believe this is being driven by climate change."

Wright is both concerned and hopeful about solutions that are being presented by politicians.

She's skeptical of carbon capture technology, for example, a process where carbon-emitting industries also develop the technology to suck it out of the air and trap it into the ground.

"The same communities that suffered from petrochemicals will now suffer from carbon capture sequestration, an untested process for pulling carbon from the air," she said, adding that in the past, the growth benefits from burgeoning industries in Louisiana have not reached vulnerable communities.

Her hope is that the solutions will come from a grassroots level, where the communities that are affected will decide their future.

That's certainly what Guidry is trying to do in her own personal activism. She will talk to anyone who will listen about Lake Charles and the help they’re not getting.

"We're going to be a city underwater, I actually believe we're going to be underwater within the next 10 years. It's already affecting the farmers," she said.

"It is a choice to live here, I get that. But without us being here, you lose your rice and your soybeans and your crawfish and your seafood. So if we don't get the help, you're also losing a natural resource. We provide so much to the United States."

Cities like Lake Charles are at a crossroads — will they be left to drown or will innovative and robust climate policy help save them?

"We're definitely at a precipice right now," said Guidry.

"The gamechanger is going to be, of course, electing people that have our best interests at heart, politicians that are not bought, but are actually there to serve."

WATCH | Lake Charles residents say race and poverty mean recovery efforts haven't matched climate devastation: