May 30, 2019

On a hot summer afternoon in Winnipeg's Market Square in 1917, a crowd of 2,000 listened to labour activists urge them to resist conscription and burn their military registration cards.

An enraged mob of 1,000 soldiers shoved through the crowd to get to the speakers.

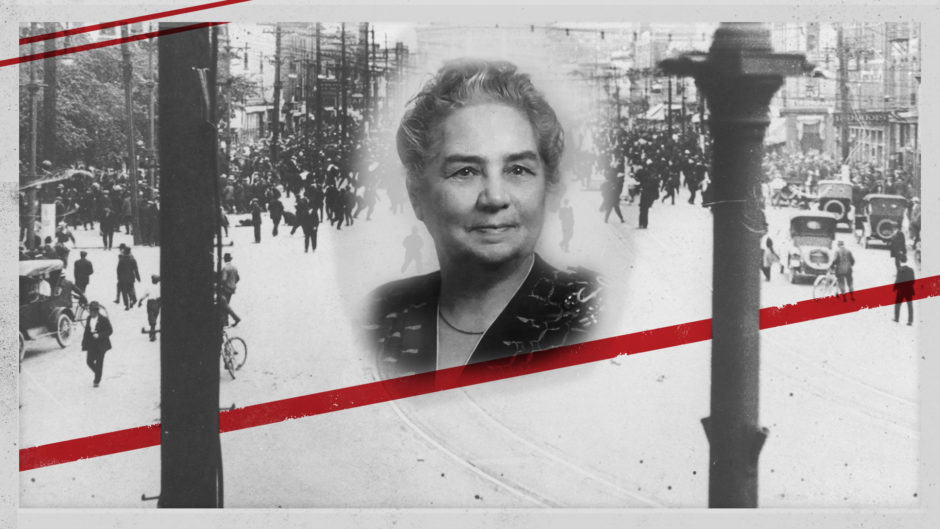

Some of the activists fled. Others — including Helen Armstrong — stayed and fought back.

At 42 and standing scarcely five feet tall, the stocky woman held her own against men in their 20s and 30s.

"She didn't seem to fear for her personal safety. That's just part of who she was," said Paula Kelly, who created the 2001 documentary film The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong.

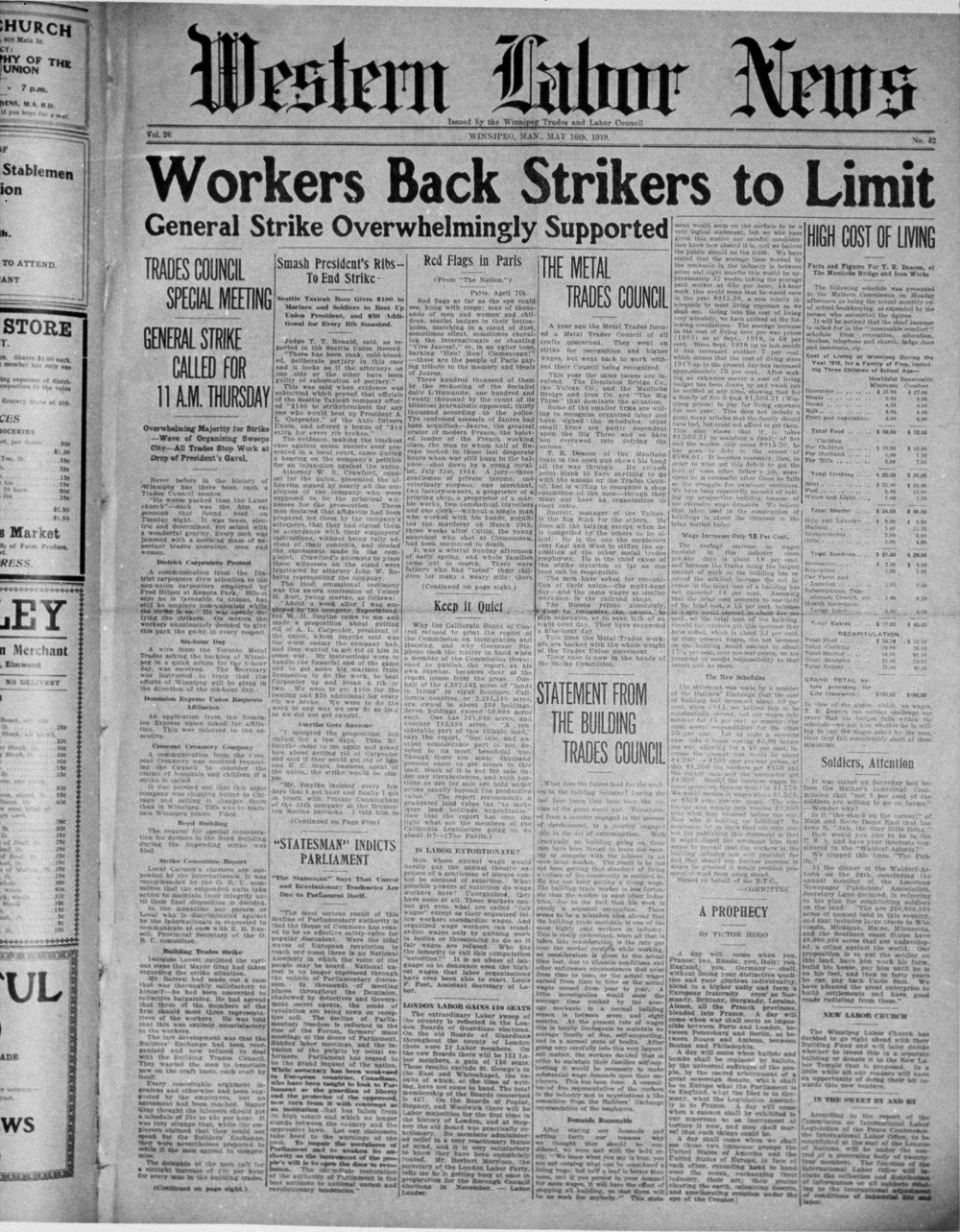

That strength of character propelled Armstrong into bitter union organization battles, the turbulence of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike and more jail cells than any other person during the six-week uprising of 25,000 to 35,000 workers in the city.

Armstrong was a towering presence during the general strike — such a force that she earned the nickname "Wild Woman of the West" from some newspapers in Eastern Canada.

"I think I can encapsulate her character in two words: courage and compassion," Kelly said. "She never stopped thinking about the needs of other people and anticipating those needs."

Her given name was Helen, but at a time when women were considered second-class citizens, most newspaper reports called her Mrs. George Armstrong.

To those who knew her best, she was Ma.

She was the matriarch of the strike, fiery and benevolent at the same time, standing with men while championing the cause of women.

"Girls have got to learn to fight as men have had to do for the right to live, and we women of the labour league are spending all our spare time in trying to get girls to organize as the master class have done to protect their own interests," Armstrong wrote in a 1917 letter to the editor of the Winnipeg Telegram.

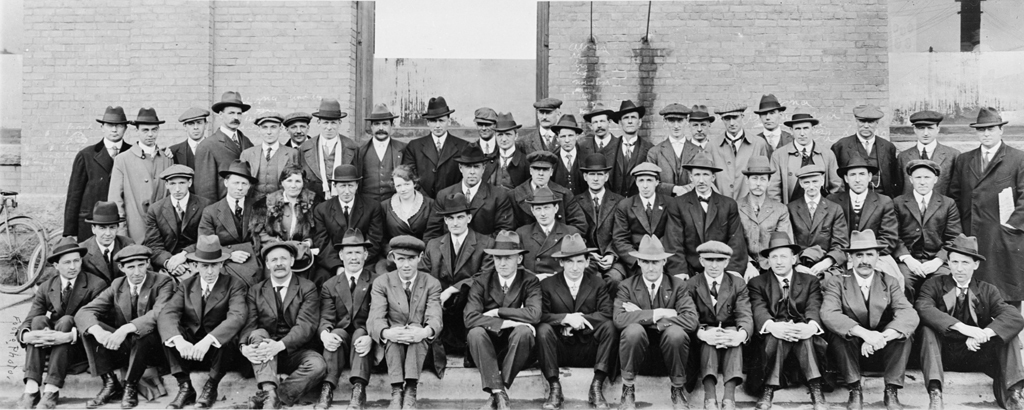

She was one of only two women on the 53-member strike committee in 1919 but was one of the most active — and most frequently incarcerated — of them all.

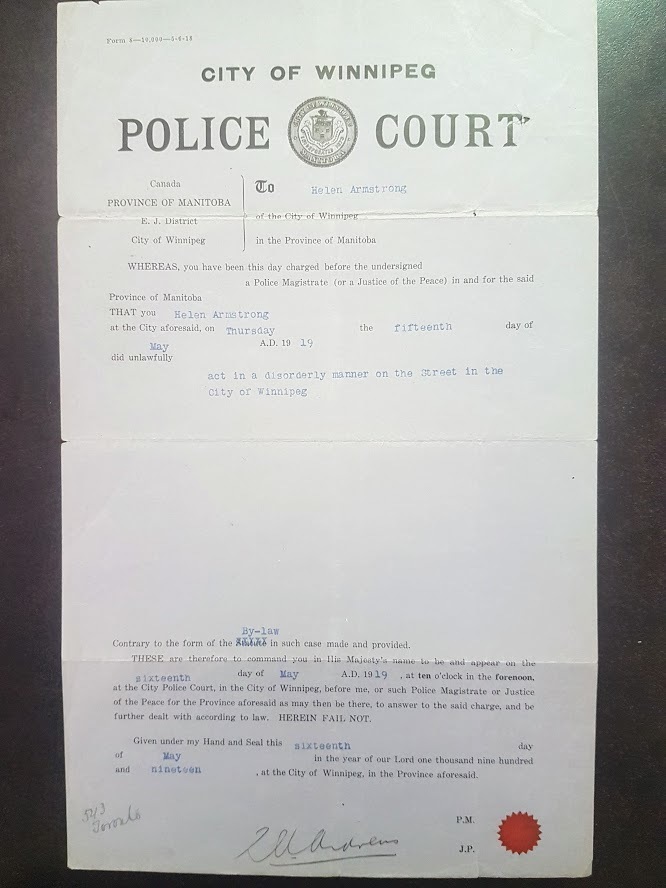

On the first day of the strike, May 15, 1919, she was charged with disorderly conduct for her vocal part in the protests.

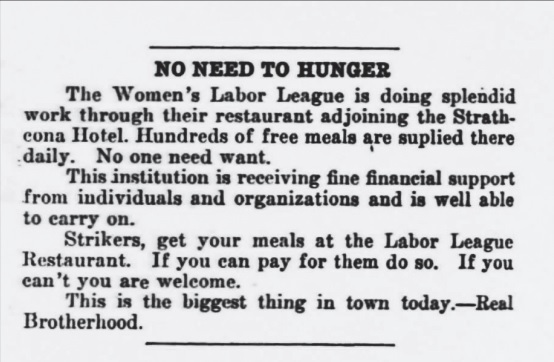

During the strike, Armstrong established a soup kitchen, which she called the Labour Café, to feed female strikers.

Women were provided three free meals a day while men, who were also welcome, were encouraged to pay whatever they could.

"She understood that the girls who were striking risked everything and were not going to be able to feed themselves," Kelly said.

On the front lines, Armstrong was a visible presence who harassed anyone who crossed picket lines, encouraged women to boycott any store where the staff were striking, and challenged all women to join the strikers as a show of support.

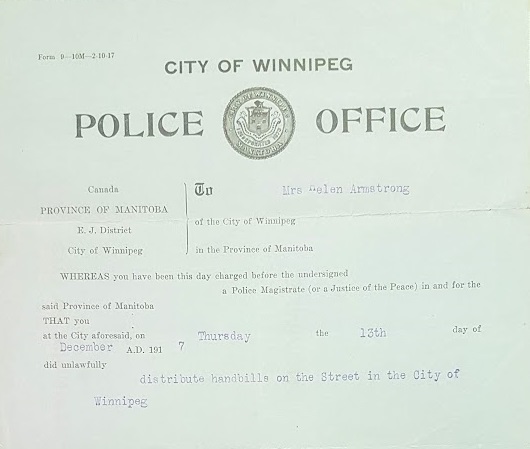

Her efforts were often aggressive, which is why she caught the attention of police.

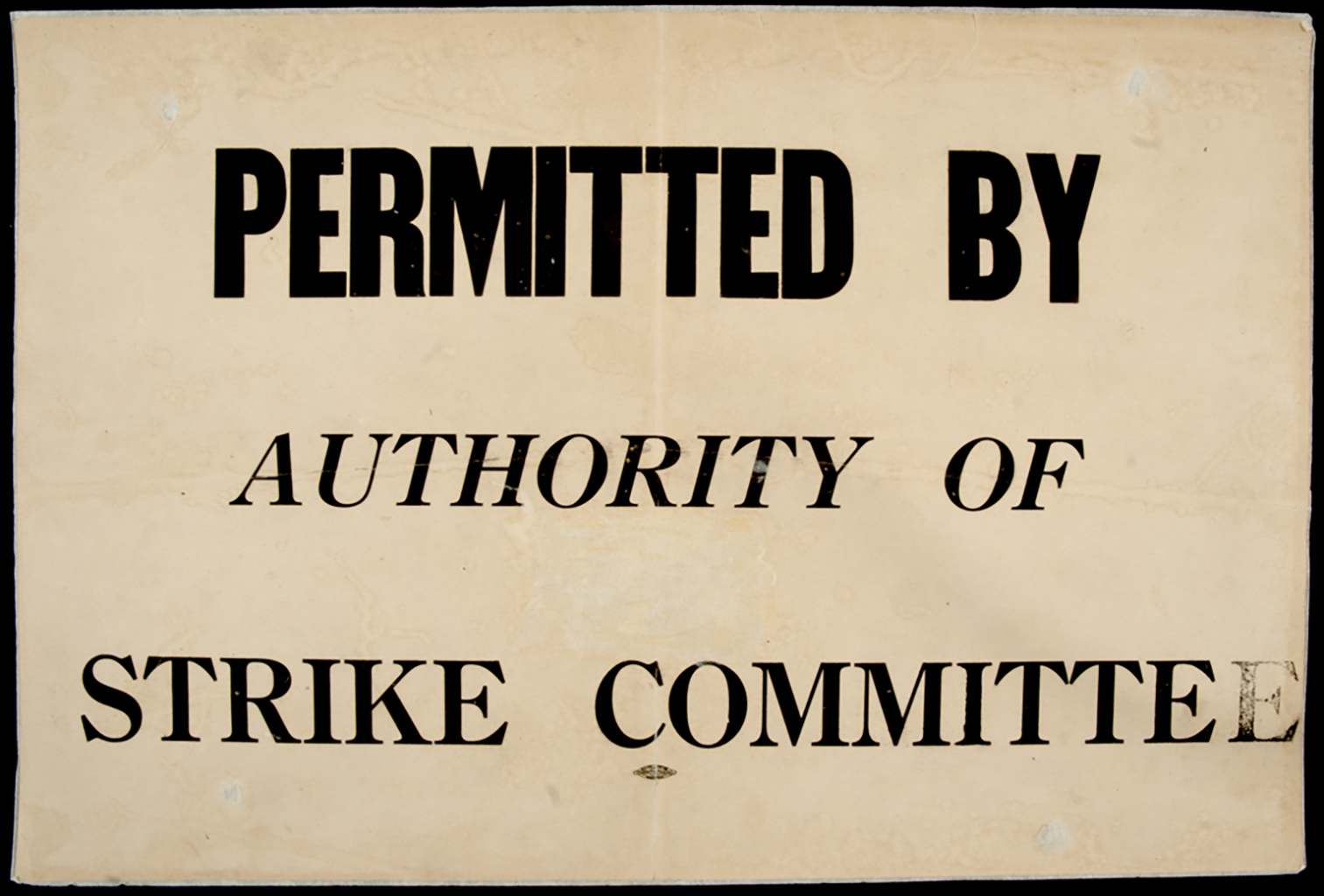

She earned the label "female Bolshevicki" from the anti-strike newspaper, the Citizen, for encouraging women to blockade their neighbourhoods against delivery wagons that did not have strike committee-approved permission cards.

After Mayor Charles Gray ordered a ban on public crowds and parades in early June, Armstrong was still out there, getting charged for unlawful assembly.

"She didn't mince words, didn't pull punches and didn't care what people thought of her, obviously," Kelly said. "Clearly, she was not concerned about consequences. She was concerned about action and making issues visible and making change."

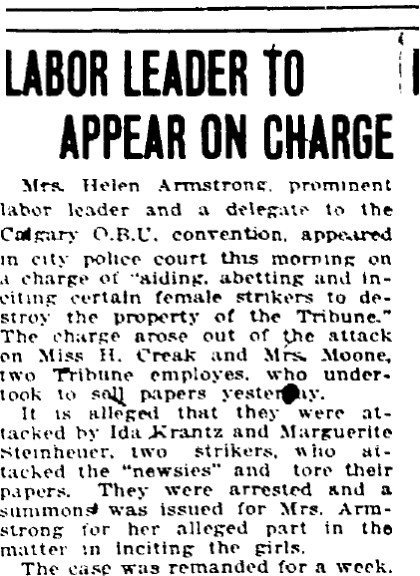

In addition to unlawful assembly and disorderly conduct, she also was charged with inciting strikers and counselling to commit an indictable offence.

'She didn't mince words, didn't pull punches and didn't care what people thought of her, obviously.'

The latter was for allegedly encouraging two women, Ida Krantz and Marguerite Steinheuer, to assault Winnipeg Tribune employees selling newspapers on the street in late June.

Krantz and Steinheuer were fined $5 each but the Tribune reported two days later that the "notorious" Armstrong was still behind bars to keep Winnipeg safe.

Passion for social reform

Though Armstrong's notoriety grew during the strike, her reputation as a radical activist had already been well established.

Born in Toronto in 1875 as Helen Jury, she often helped her father, Alfred Jury, in his tailor shop. A proponent of the working class, he helped co-found a Canadian chapter of the Knights of Labour, an organization that campaigned for a shorter work day.

Armstrong watched as labour leaders, trade unionists, socialists and others discussed and debated issues with her father, seeding her own passion for social reform.

One regular visitor to the shop was a young carpenter named George Armstrong, whom Helen later married.

They moved to Montana, where George worked building infrastructure for mines.

When sickness swept through the camps, Ma Armstrong organized the women in the brothels and saloons into a pseudo nursing corps to tend to the miners, wrote Bob Waters, Armstrong's grandson, in Four Generations that Walked the Walk, a book about labour activism in his family.

"This was the first example of my grandmother's desire to lead in an effort for the benefit of others," he wrote.

When the work ran out in Montana, the couple moved to New York City, where Armstrong joined the National Woman Suffrage Association and first saw the inside of a jail cell.

She and others were arrested after chaining themselves to a fence around the White House during a campaign to win women the right to vote, Waters wrote.

Bustling Winnipeg lured the Armstrong's back to Canada in 1905.

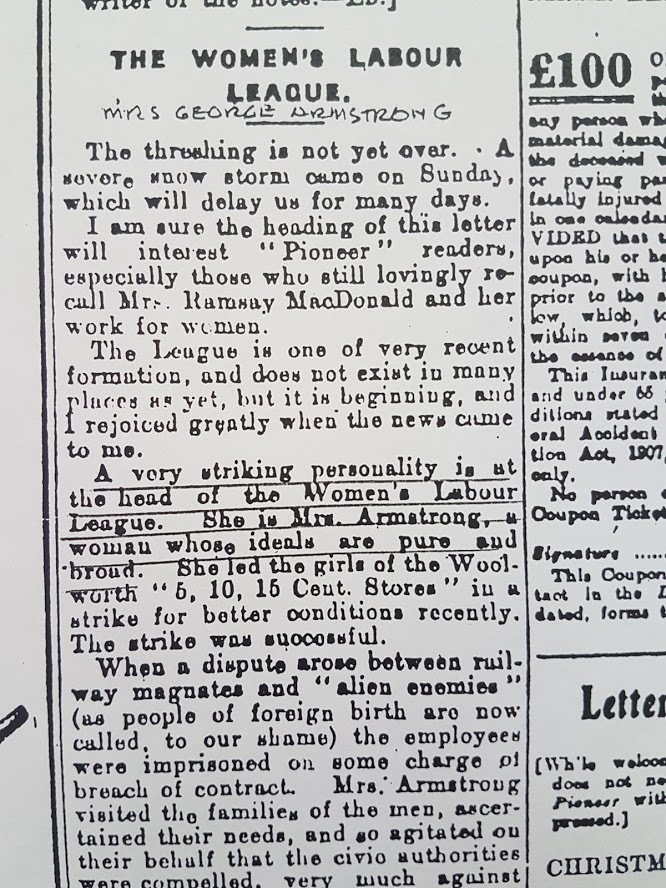

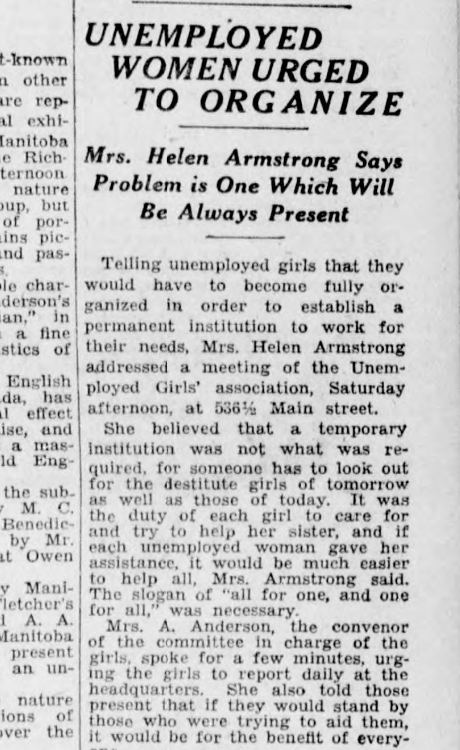

In 1917, Armstrong took on the job of rejuvenating the dormant Women's Labour League, which encouraged working women to join or form unions and get involved in political advocacy.

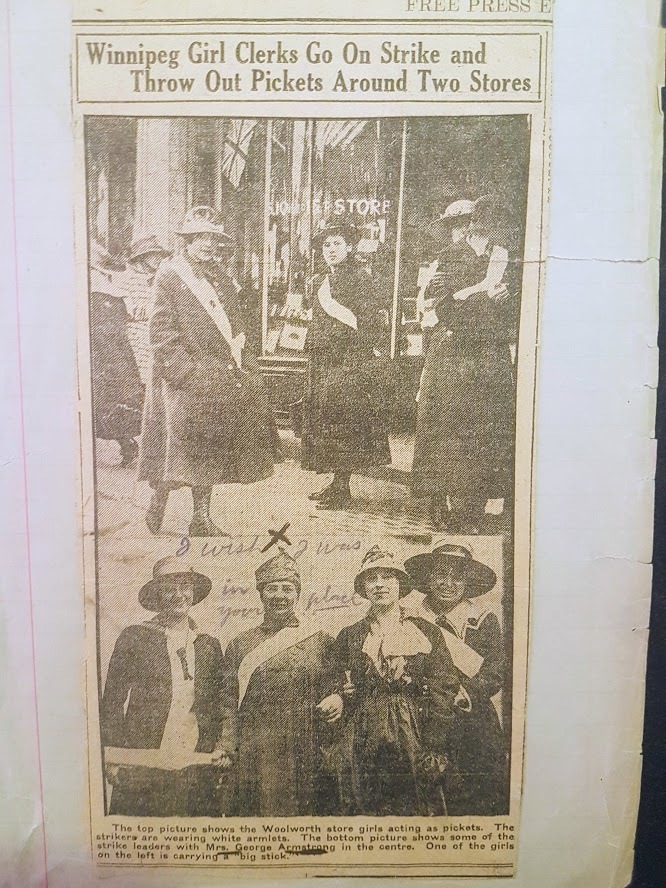

She walked the clerks at Woolworth's department store out on strike that same year.

Women employees at Woolworth's earned as little as $6 per week, and worked 12 hours a day, six days a week. They demanded an $8 per week minimum, union recognition and a half-day holiday.

Armstrong picketed alongside the women, shoving back at constables who tried to disperse them, and also negotiated at the table. She pressured the city's Trades and Labour Council to put together a strike fund to help cover the women's lost wages.

The strike, which lasted from May 26 to June 11, had mixed results, Esyllt Jones wrote in Fighting Days: Women's Employment and the Right to Work in Manitoba, an essay published by the Manitoba government.

Woolworth's agreed to improved wages and days off but refused to recognize the union, and most of the women lost their jobs because the company hired replacement workers.

When George Armstrong's carpenters union went on strike in 1917, Armstrong delivered food to the families and picketed alongside the men — sometimes her encouragement on the line was so vociferous she put the men to shame, Harry and Mildred Gutkin wrote in their book, Profiles in Dissent: The Shaping of Radical Thought in the Canadian West.

Armstrong organized housemaids the same year and was elected president of the new Hotel and Household Workers' Union in Winnipeg.

Minimum wage campaign

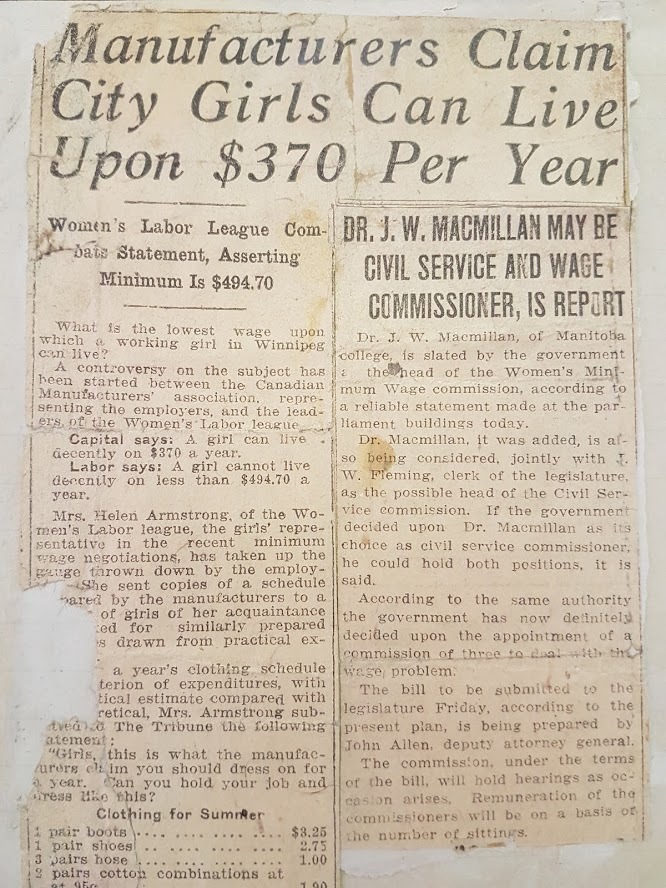

She also led a campaign for minimum-wage legislation for women in Manitoba that would be equal across the board, regardless of industry or age.

While the provincial government in March 1918 created a minimum wage board that established a base pay of $11-$12 per week, depending on the industry, employees weren't entitled to it until they had worked at least 18 months in one place, and there was a different wage scale for minors.

Armstrong again chastised the government in February 1919, saying the minimum wage board was wasting time and public money by picking various pay rates and conditions.

"There was no issue that had a negative impact on the working class that my grandmother heard of where she failed to put herself in the middle of it," Waters wrote.

She even went after the owners of bakeries in Winnipeg after learning they were putting out lighter loaves than required by law, he wrote.

She gathered 500 housewives at a meeting and crafted a letter to the mayor and council expressing their disappointment. In response, council approved a resolution to enforce the bread bylaw.

Fighting conscription

Armstrong also lobbied governments for better pensions for soldiers' wives and children and was particularly fiery in her objection to conscription during the First World War.

She argued that providing good allowances and pensions to dependants of anyone who enlisted would increase the volunteer pool.

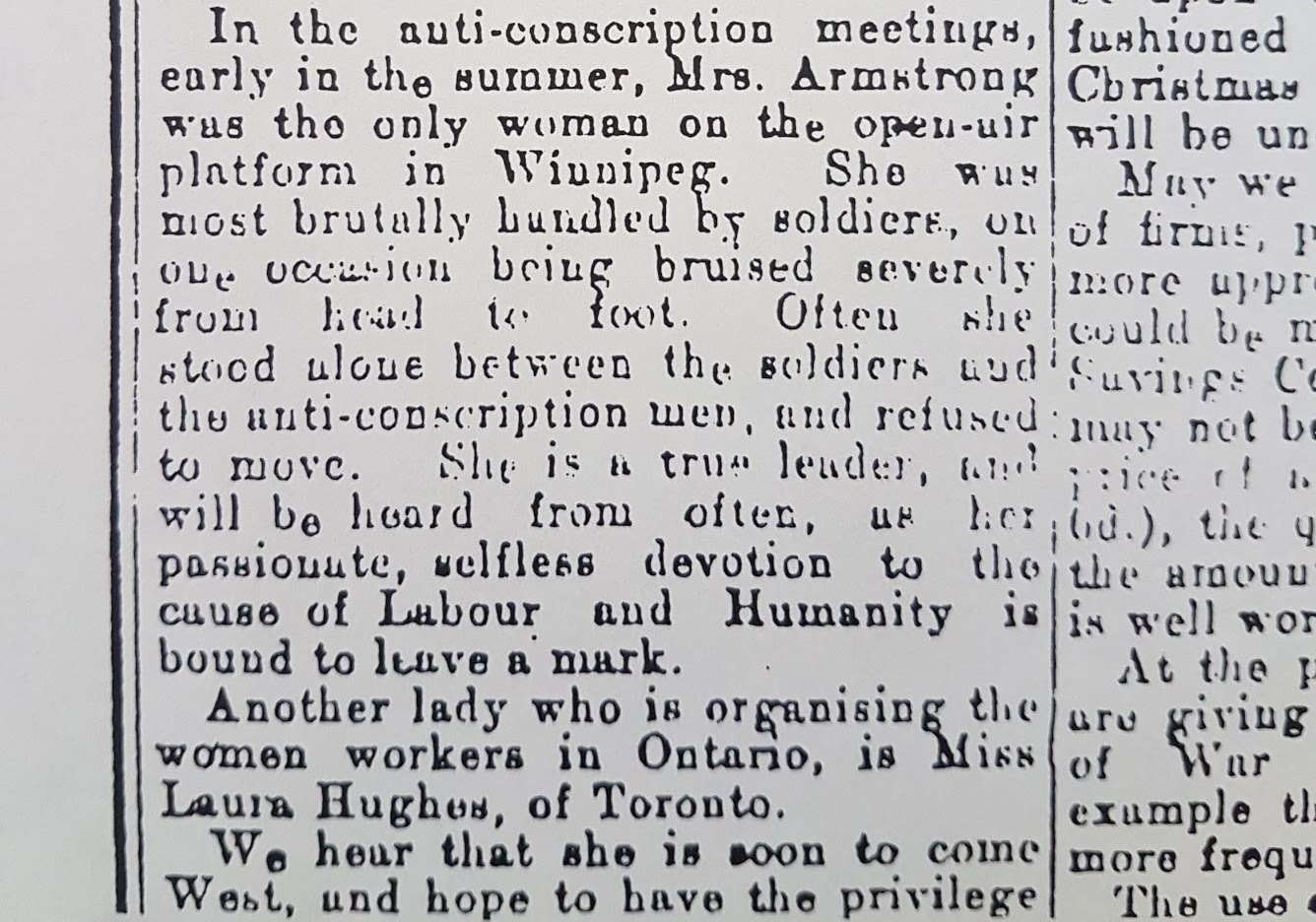

During anti-conscription meetings, Armstrong was usually the only woman standing on the open-air platforms, according to Gertrude Richardson, a labour newspaper columnist quoted in Barbara Roberts's book, A Reconstructed World: A Feminist Biography of Gertrude Richardson.

When those speeches were met with violence, Armstrong stood her ground and was often left "bruised severely from head to foot," Richardson wrote.

Armstrong also fought for women's right to vote.

"She felt all women should have the vote, that there should be no limitations and no restrictions," Kelly said.

"She understood that without the vote, women had no chance to get into the political arena and make the kind of change for social justice that she wanted to see made."

Armstrong's social justice stances separated her from many high-profile middle-class suffragists of the time, such as Nellie McClung, who opposed unions, often took anti-immigrant stances and was a supporter of conscription.

'She was certainly a figure that deserves at least as much recognition as someone like Nellie McClung.'

Armstrong vigorously fought for women regardless of their class or occupation — laundresses, retail workers, stenographers, telephone operators, the list went on and on, Kelly said.

"Helen Armstrong was often also involved in organizing women in the sex trade industry," said Sharon Reilly, the former curator of social history at the Manitoba Museum.

In one letter to the deputy minister of labour, Armstrong wrote that poor wages and constant layoffs left many women with little choice but to work on the street, which "claims them as easy prey."

"She was certainly a figure that deserves at least as much recognition as someone like Nellie McClung," Reilly said.

Queen and Hancox

Armstrong did have some strong allies.

Katherine Queen, wife of strike leader John Queen, was a Women's Labour League member who fought alongside Armstrong for minimum wage and against conscription.

Queen established the Labour Women of Greater Winnipeg in the 1920s, after the labour league dissolved. She led it more directly into politics, pushing for birth-control clinics, provincial medical insurance and government-run health facilities.

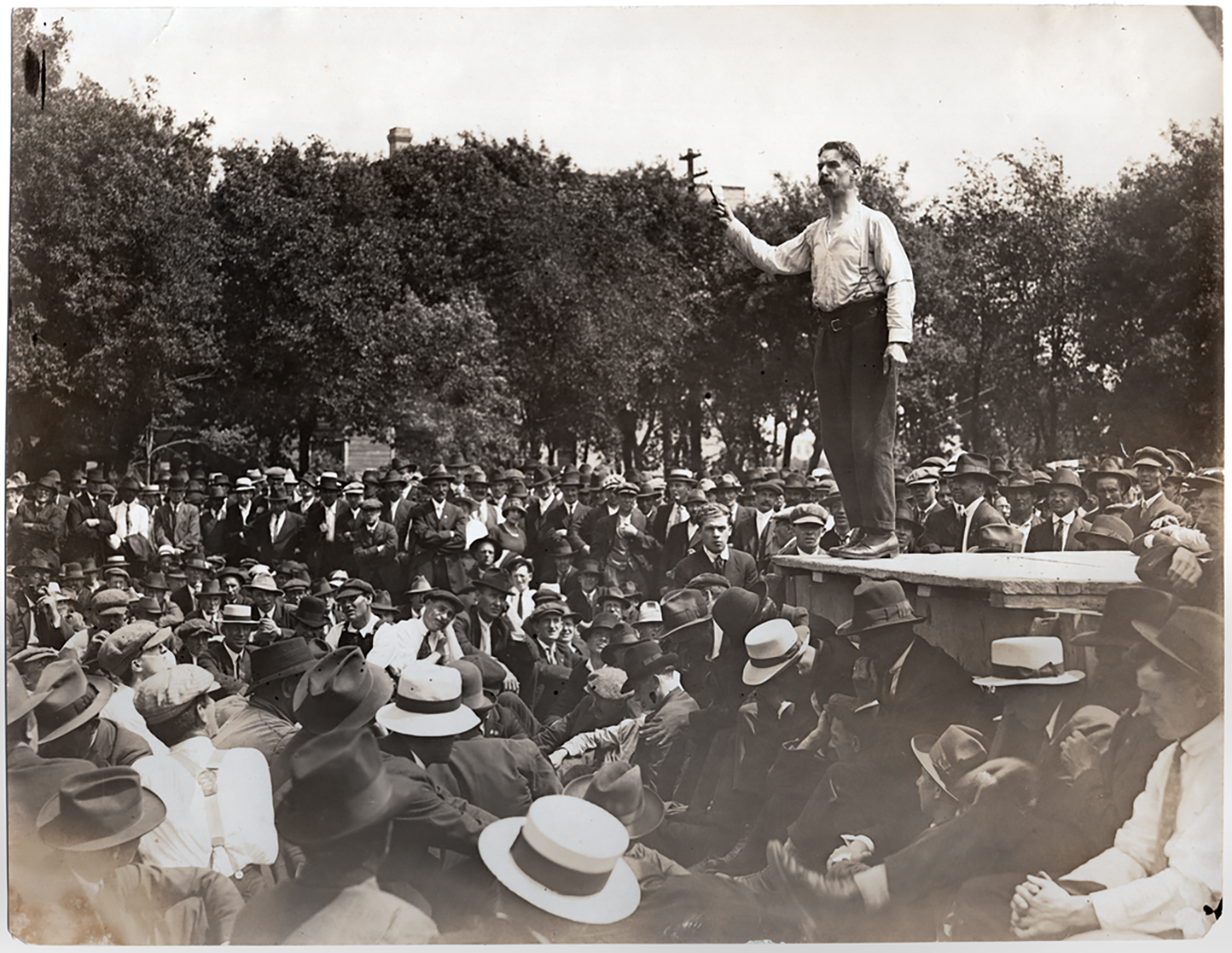

Edith Hancox, another women's rights activist and labour league member, was perhaps the only woman to address a mass meeting at Victoria Park during the Winnipeg General Strike, Reilly said.

"Even before the strike, the women in the Women's Labour League, like those three, were fighting to increase women's roles in the public sphere and to help other women however possible," Reilly said.

Armstrong's work for women established her, in particular, as a voice of the far left and earned her a spot as the only woman on the Trades and Labour Council and one of very few women to attend the June 1919 founding convention of the One Big Union in Calgary.

It also made her a valuable member of the 1919 Central Strike Committee, which had 53 members but only two of them women. The name of the other woman is not known.

"She was pretty fierce, pretty strong, wonderful leader; very compassionate and worked very, very hard," Reilly said of Armstrong.

Hello Girls

When the Winnipeg General Strike began on May 15, 1919, the first to walk out were 500 telephone operators known as the Hello Girls.

Their desks were empty at the beginning of their 7 a.m. shift, even though the strike's official start was set for 11 a.m.

"They were pretty disgruntled with their working conditions. They were paid very poorly, they were treated very poorly," Reilly said.

About 10 per cent of the 1919 strikers were women, mostly from commercial bakeries, confectioners and garment manufacturers, and with their own issues — most notably, equal pay for equal work.

Family members of strikers also often walked at their sides. Including them, the strike brigade made up more than half the city's population of 175,000, historians Nolan and Sharon Reilly said.

While the vast majority of news reports and photographs from the strike focused on men, and only two women were on the 53-member Central Strike Committee, women made the movement's engine run.

"Many women walked out on strike, union or not union, and then other women were supporting those who were on strike or were off during the day at the marches and so on," Sharon Reilly said.

"The women were making the wheels turn around, as it were, because somebody had to support all of those folks who were out on strike."

Reports from the time say 1,200 to 1,500 meals a day were served at the Labour Café, which started in the Strathcona Hotel on the corner of Rupert Avenue and Main Street.

It was forced to move after 10 days. Some accounts say the Citizens' Committee of 1,000 — the anti-strike organization that included much of the city's upper class — pressured the owner to disallow its operation.

It moved to the Oxford Hotel on Notre Dame Avenue and finally, the Royal Albert Arms Hotel on Albert Street in the Exchange District.

There's no way the strike could have lasted so long without the women, said Julie Gard, professor of history and labour studies at the University of Manitoba.

"If people can't eat, if the children aren't being cared for, if the picketers aren't being fed on the picket lines … I'm not sure how this would have worked. Women were critical."

There were also women on the other side.

On June 9, the city fired nearly the entire police force for refusing to sign a loyalty pledge — the "slave pact," as it became known — promising never to participate in a sympathetic strike.

Among those who stayed on the job were Mary Dunn and Jane Andrews, the first two policewomen in Winnipeg's history.

Women also were appointed by the Citizens' Committee to fill some positions left vacant by the strikers, including gas jockeys to keep vehicles running, streetcar operators and telephone operators (who occasionally had their cables unplugged and sabotaged by the Hello Girls).

Salute to women

On June 12, one of the mass gatherings in Victoria Park was declared Ladies Day as labour leaders acknowledged the work of all the women who supported the strike.

James (J.S.) Woodsworth also made a famous speech promoting equality of the sexes.

In the coming days, he told the crowd, women would take their place side by side with men, not as dependants or inferiors, but as equals; the strike was part of the great movement for the emancipation of women.

At the conclusion of his speech, many women and girls shouted: "We'll fight to the end," according to Saving the World from Democracy: The Winnipeg General Sympathetic Strike, a booklet published by the strikers defence committee in 1920.

The Women's Labour League also created a relief committee that provided cash donations to women in need, helping those on strike to pay their rent and other expenses.

Armstrong also used the strike as an opportunity to further her efforts to unionize retail clerks, particularly those working in smaller stores, Esyllt Jones wrote in her essay Fighting Days.

Paula Kelly described Armstrong as "a true leader" who was looked upon as a mentor.

"She had her own office in the Labour Temple. She was gathering the troops, the women on the front lines of the strike, and they relied on her guidance and advice and looked to her for inspiration," Kelly said.

Helen Hogg describes her experience working at Eaton's during the strike and walking off the job to show her support. (Manitoba Museum)

Arresting George

On the evening of June 16 and into the early hours of June 17, the North-West Mounted Police carried out a number of raids at the homes of strike leaders.

When they arrived at George and Helen Armstrong's house, things didn't go smoothly.

According to several reports in books about the strike, Armstrong held the officers at bay, telling them they couldn't take her husband until she spoke to police Chief Christopher Newton. She wanted to be assured the arrest warrant was legitimate.

She made them wait while she dashed to the closest police station and called the chief on a telephone. Once she had his personal certification of the warrant, she ran back to the house and released George to the arresting officers.

The raid on strike leader George Armstrong's home, as recalled in 1969 by neighbour Mary Jordan.

Despite her highly visible involvement in the strike, Helen Armstrong was not arrested and tried with the other leaders.

"As if radical dissent by a woman could not be taken seriously," wrote authors Harry and Mildred Gutkin.

Instead, Armstrong stood outside the jail and led the singing of Solidarity Forever.

Hatpins and horse rumps

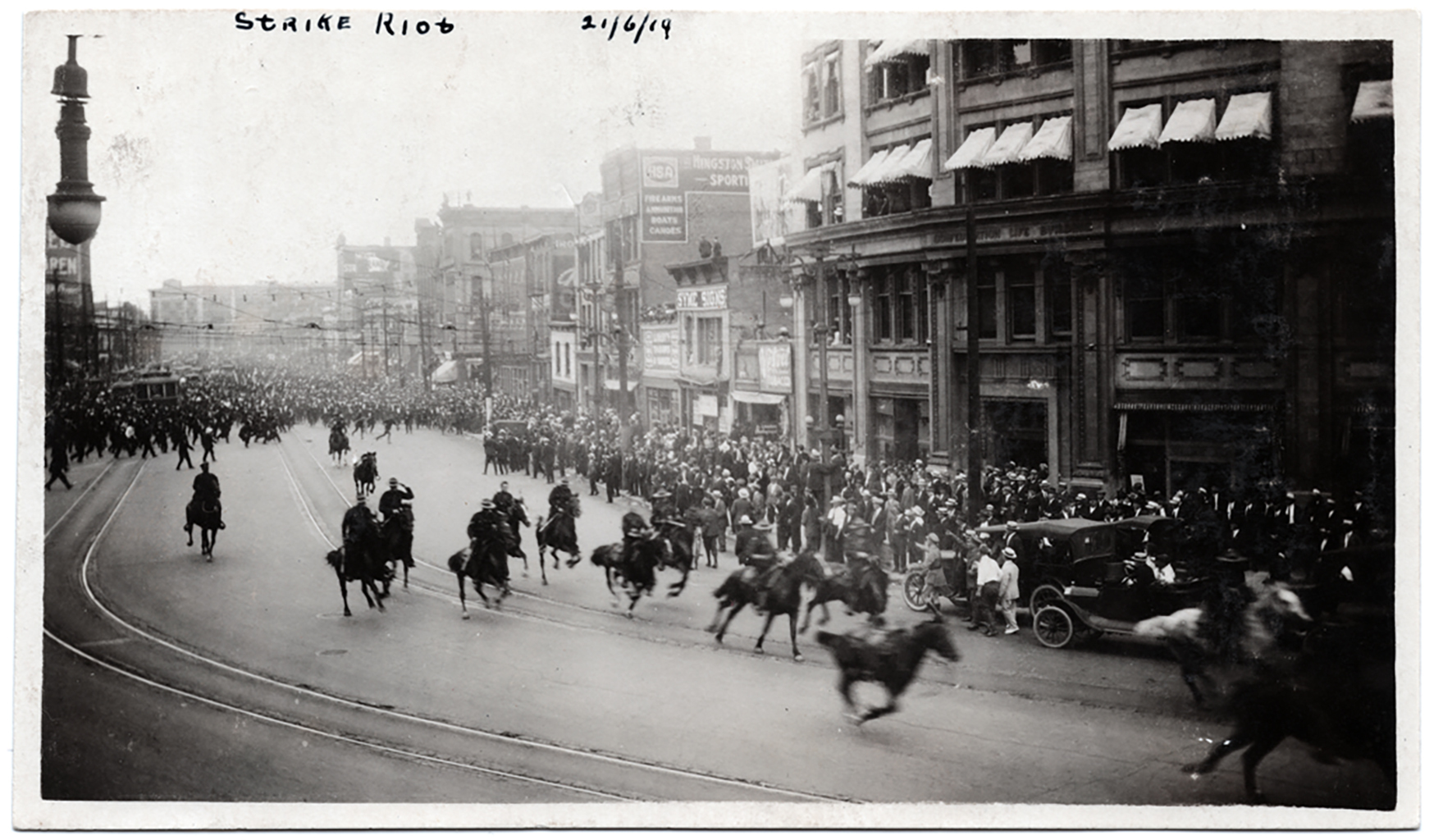

Armstrong was part of the crowd on Bloody Saturday, the riot on June 21 that saw police run their horses through crowds, club bystanders and fire their guns. In the end, two men were dead and dozens were injured.

As the police passed, she urged the women around her to use their hatpins and poke the backsides of the horses, Merna Forster wrote in her book 100 Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces.

The strike officially came to an end five days later. All workers were asked by the strike committee to return to their jobs.

For many, there wasn't anything to go back to, as some employers refused to rehire them. Others had to reapply, losing seniority and starting over with entry-level wages — and they were rehired only after signing the "slave pact."

Armstrong's Labour Café closed about a week after the end of the strike.

She then took to the floor of the Trades and Labour Council to demand aid for the many women strikers who lost their jobs, Harry and Mildred Gutkin wrote.

A fighter throughout life

Armstrong continued as a union organizer and advocate for women after the strike and during the Depression.

On Labour Day in September 1919, a parade of 7,000 protesters filled the streets of Winnipeg. The Women's Labour League had two floats in the parade, co-ordinated mainly by Armstrong, portraying the figures of liberty, equality and fraternity.

A couple of days later, Armstrong spoke to a mass meeting of people protesting the strike leaders' arrests, echoing calls to take the fight to the political arena.

"Women's vote has given us the club. Now we want women to use it," she said.

She also travelled across Canada, making public appearances to raise a legal defence fund. Newspapers in Eastern Canada, reporting on her efforts, referred to her as "the Wild Woman of the West."

In 1921, she helped persuade the government of Manitoba to become one of the first two Canadian provinces to institute a Minimum Wage Act for women. The hourly rate for women was 25 cents per hour.

In 1931, the act was amended to include boys under 18, and in 1934, the statute finally was amended to include men.

In November 1923, Armstrong ran for a seat on Winnipeg's city council but lost.

George had served in the provincial government with the Socialist Party of Canada, winning a seat in 1920, while still in jail, but was defeated in 1922.

Blacklisted by employers, he was unable to find work in Winnipeg, so the couple moved to Chicago. The 1929 stock market crash chased them back to Winnipeg and Armstrong picked up right where she left off.

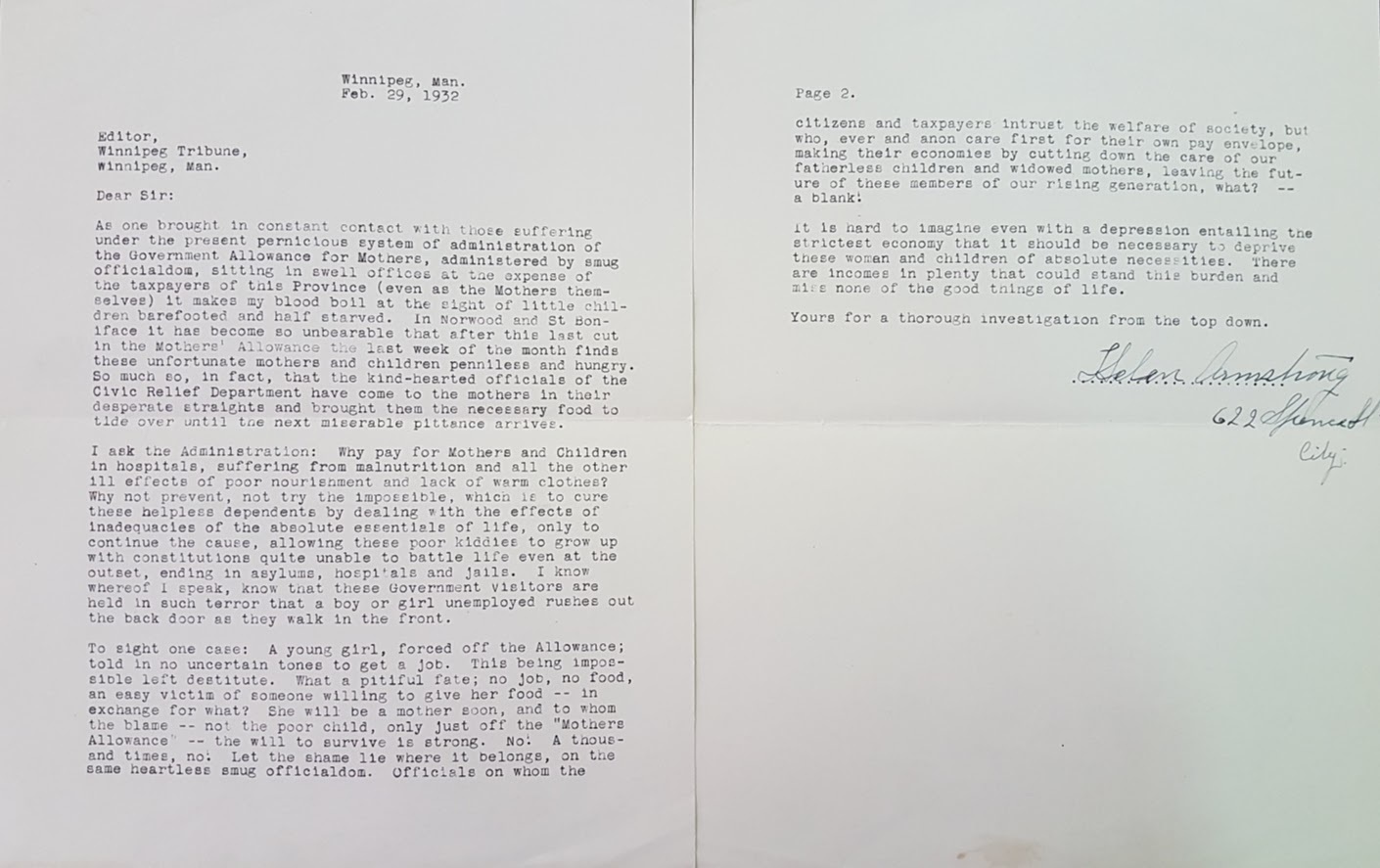

The mothers' allowance for widows and single women was one of her passions.

"She was a fierce advocate for that. She brought people in difficult circumstances into their home, she fed people from her own kitchen," Kelly said. "There was just really no end to her generosity and she didn't confine her attention to just one issue.

"She looked for where the need was and sort of rushed in to try to wake people up."

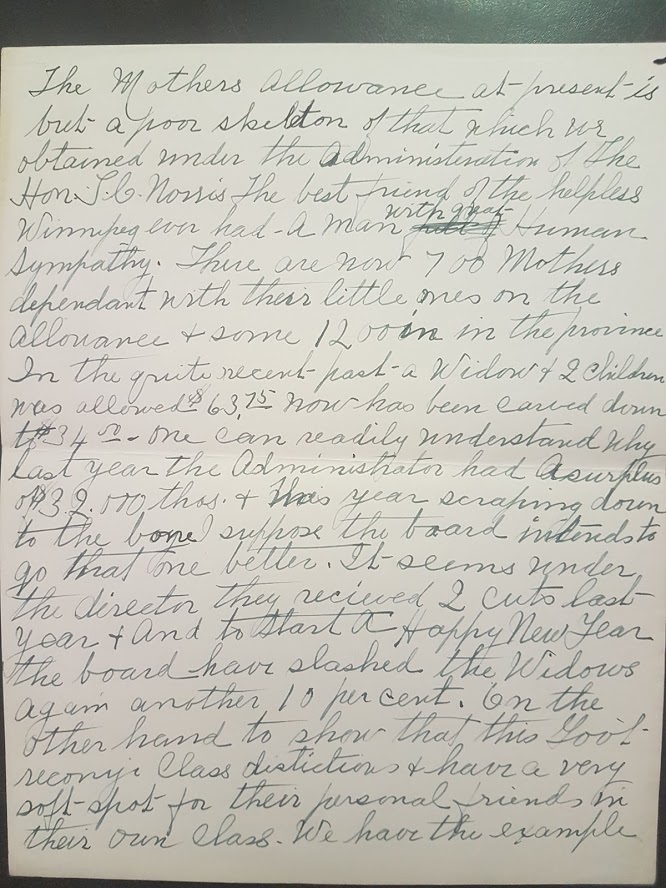

In a handwritten letter in the provincial archives, Armstrong wrote about a mother of two getting her monthly allowance slashed from $63.75 to $34. Meanwhile, lawyers hired to work on allowance revisions for the government were paid $175 per day for 55 days.

Another mother had her allowance cut back because she had a small garden to cover some food needs, Armstrong wrote.

"[Armstrong] always backed up what she claimed. She was very shrewd in that way," Kelly said.

The Armstrongs moved to Victoria around 1945 and later to California to be near one of their daughters.

She died in 1947 at age 72. He died in 1956 at age 85.