December 14, 2021

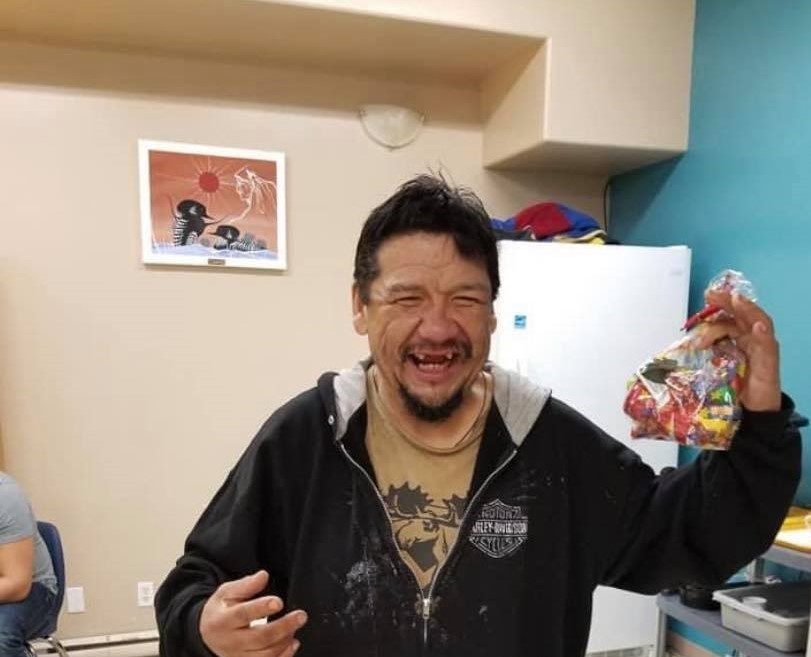

The last time Jeremy Ettawakapow saw his father alive, he looked happy.

John Ettawakapow was with friends, smiling and bragging to everyone that Jeremy was his son.

Jeremy never thought his father’s life would be cut short inside a northern Manitoba RCMP holding cell.

"He should have been anywhere else besides that jail cell," he said.

John Ettawakapow was among the dozens of people arrested while intoxicated who have died in police custody after they weren't monitored properly or their medical condition wasn't addressed, a CBC investigation has found.

The investigation examined roughly 250 deaths in police custody in Canada since 2010 by searching media reports, coroners' inquests and reports following investigations of in-custody deaths.

It found 61 of those deaths involved Canadians who were detained related to public intoxication. The majority were sent to a cell for the night because police thought they were a danger to themselves or others.

That includes a B.C. teenager who died after being sent home from an RCMP detachment barefoot, only to be re-arrested hours later and then found unresponsive in her cell.

It includes a new father in Nova Scotia on his way to see his child in hospital, only to instead suffocate on his own vomit in a jail cell.

And it includes John Ettawakapow, a beloved man from the northern Manitoba town of The Pas, who was put into a cell with two others and found dead after one of the other men's legs rolled onto his throat, possibly suffocating him.

"They didn't care," said Jeremy Ettawakapow. "They should have been watching them."

CBC's investigation found 17 cases where someone died after their medical condition was downplayed or ignored, and 13 where someone died after they were not properly monitored by police officers or guards.

The investigation also found:

- Half of the 61 documented in-custody deaths involving people arrested for public intoxication or similar offences occurred in RCMP detachments.

- The majority were detained in rural police detachments, often in communities where there are no detox or sobering centres.

- In three cases, the deaths were not investigated by a police watchdog and no coroner's or chief medical examiner's inquest was called.

'I never cried so hard in my life'

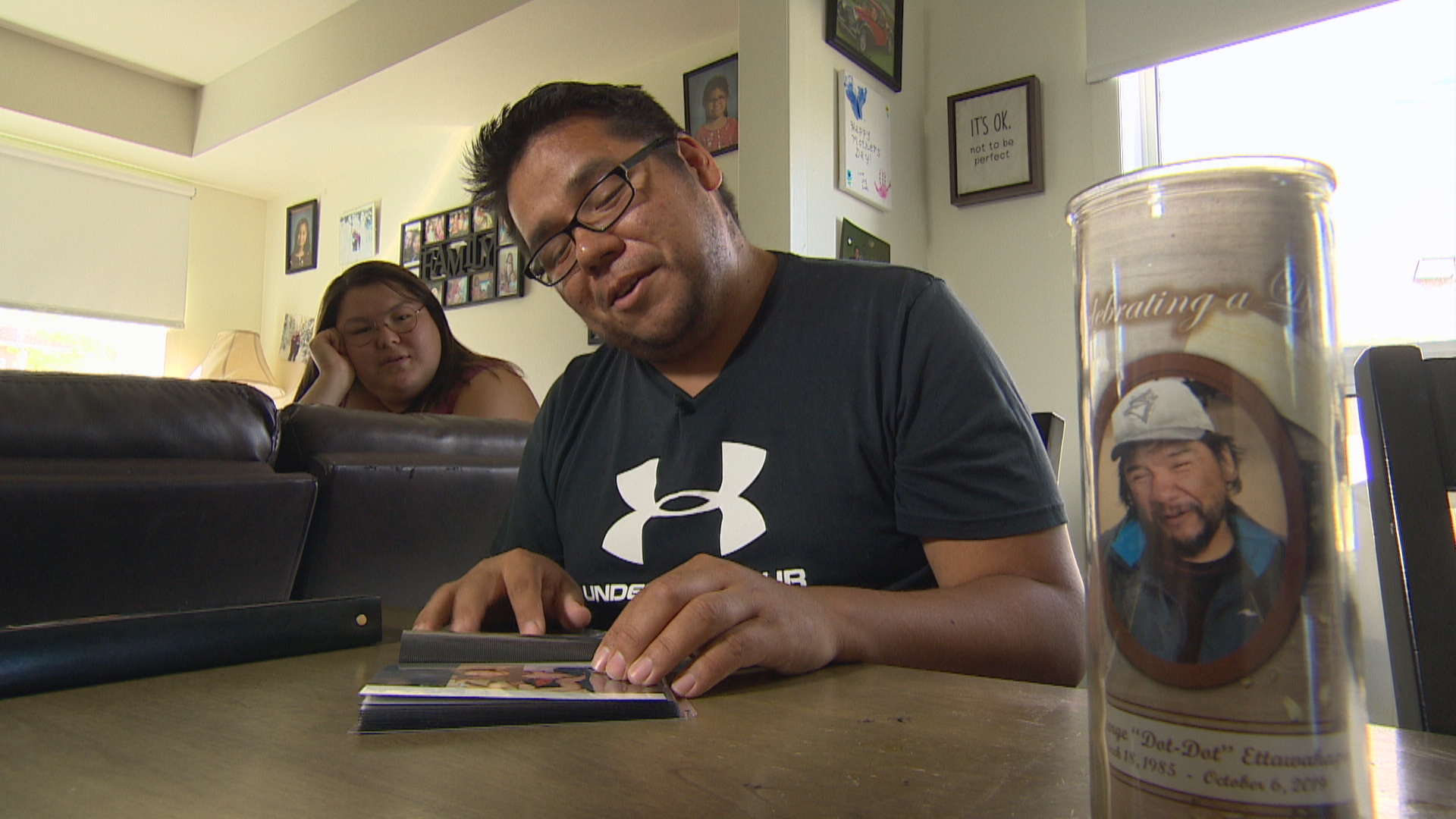

Jeremy Ettawakapow was 31 years old in 2019, married with five children and preparing to attend teacher's college at University College of the North when the call came from his brother-in-law.

"You gotta call Moose Lake," he told him.

In his gut, he knew something was wrong.

Moose Lake, about 65 kilometres east of The Pas, was the community where his father was raised.

It is where John, a member of Mosakahiken Cree Nation, became a skilled carpenter and where, as a single father, he raised Jeremy and his siblings.

When Jeremy got his auntie on the phone, she slowly broke the news to him.

"It took a minute for her to breathe and say, 'I don't know how to tell you this, but your dad was found dead in a jail cell,'" he told CBC.

"I never cried so hard in my life."

There are 'so many what-ifs,' Jeremy Ettawakapow, 33, says as he remembers his father, John.

Over time, Jeremy has learned the circumstances that led to his 54-year-old father's death that October day.

Around The Pas, a town about 520 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, everyone knew Jeremy's father as Dot Dot.

He was warm, had an infectious smile and made friends wherever he went.

He spent his mornings at the local Friendship Centre and his nights walking around town with his friends.

On the evening of Oct. 5, 2019, Ettawakapow and his friends had been hanging around their usual spot near the Saskatchewan River.

He was drinking and passed out near a local business. It was here RCMP officers picked him up and brought him back to the nearby detachment.

Ettawakapow was placed with two other intoxicated men in the holding cell.

He was taken into custody under Manitoba's Intoxicated Persons Detention Act, which allows officers to detain someone if they are intoxicated and police fear they are a danger to themselves or others.

Provinces across the country have different variations of that legislation: in Ontario, police use the Liquor Licence Act. In British Columbia, it's called the Liquor Control and Licensing Act.

The various laws give officers the ability to detain without a warrant. Across Canada, law enforcement officials use these laws to detain over 30,000 people annually, according to a CBC analysis of numbers from RCMP and several other police forces.

'He would be alive if he didn't go to that jail cell'

There isn't anywhere in The Pas, a town of roughly 5,500 people, that is open 24/7 to take in intoxicated people.

It's widely known around town that the RCMP detachment's cell No. 7 is where those arrested for public intoxication are taken. CBC spoke to several people who have been detained in that cell, one of whom said there could be upwards of 16 people sleeping there on any given night.

Benjamin Cook, who said he frequently gets picked up for being intoxicated, told CBC that in the past, they'd be stripped down to one layer of clothing and left to sleep off their intoxication, with no mat or blanket.

"It's just … side-by-side sleeping, back-to-back," Cook told CBC. "That's the only way you can stay warm in those cells."

Following Ettawakapow's death, they're now given a blanket, he said.

The autopsy report into Ettawakapow's death shows the cell wasn't properly monitored for at least 40 minutes — the time he spent trapped with a leg on his neck, unable to move. RCMP policy says he should have been checked after no more than 15 minutes.

The autopsy report said after Ettawakapow was found dead in the cells, the RCMP reviewed the video from that evening.

It shows Ettawakapow moved his arms up a few times right after the man's calf was placed along his neck — the last time he was seen moving before his lifeless body was found five hours later.

"He was intoxicated, but he was still a human being and he needed help," said Jeremy.

"I still believe he would be alive if he didn't go to that jail cell."

Ettawakapow's death was reported to the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba — the province's police watchdog — the next day. The investigation into his death is still ongoing.

When asked about RCMP protocol for putting multiple people in one cell, the Mounties said there is no policy regarding how many people can be in a single cell.

Manitoba RCMP spokesperson Tara Seel said that's because cell sizes vary across the country.

RCMP said they couldn't discuss any details surrounding the conditions in The Pas, citing the ongoing IIU investigation.

"Any death of a person in RCMP custody is a tragedy," Sgt. Caroline Duval of the RCMP's national division said in a prepared statement.

RCMP protocol states physical well-being checks must be performed at irregular intervals, no more than 15 minutes apart, along with regular assessments of someone's responsiveness, she said.

That usually means a civilian guard physically goes to the cell to observe the detainee through the door or window, she said.

Sometimes in remote locations, there is only one guard on duty, without an RCMP officer present. For the protection of the guards, only an officer can actually enter the cells.

The guard also must ensure the intoxicated person is awake, or wake them up, once every four hours.

An autopsy was unable to conclude how Ettawakapow died but couldn't rule out the possibility he suffocated because of the leg on his neck.

Teen sent home barefoot

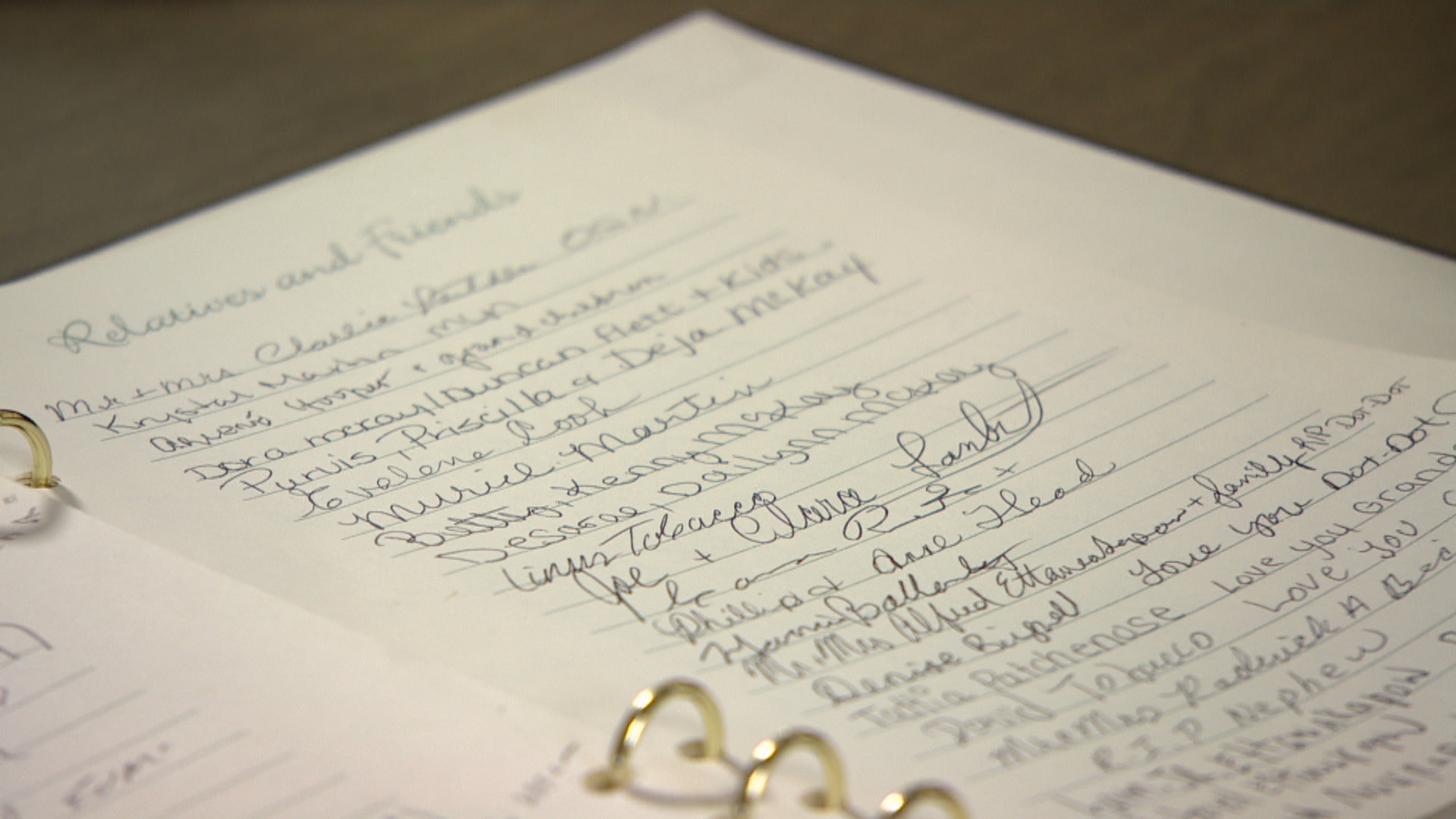

Part of CBC's investigation involved finding the friends and family of the people who died in custody and learning about who they were before they died.

In some cases, they died without ever being named in the media, and for privacy reasons, police do not typically release their names. Some died without an obituary ever being published.

Inquest reports, freedom of information requests and media reports paint a picture of what happened to these people while in police holding cells.

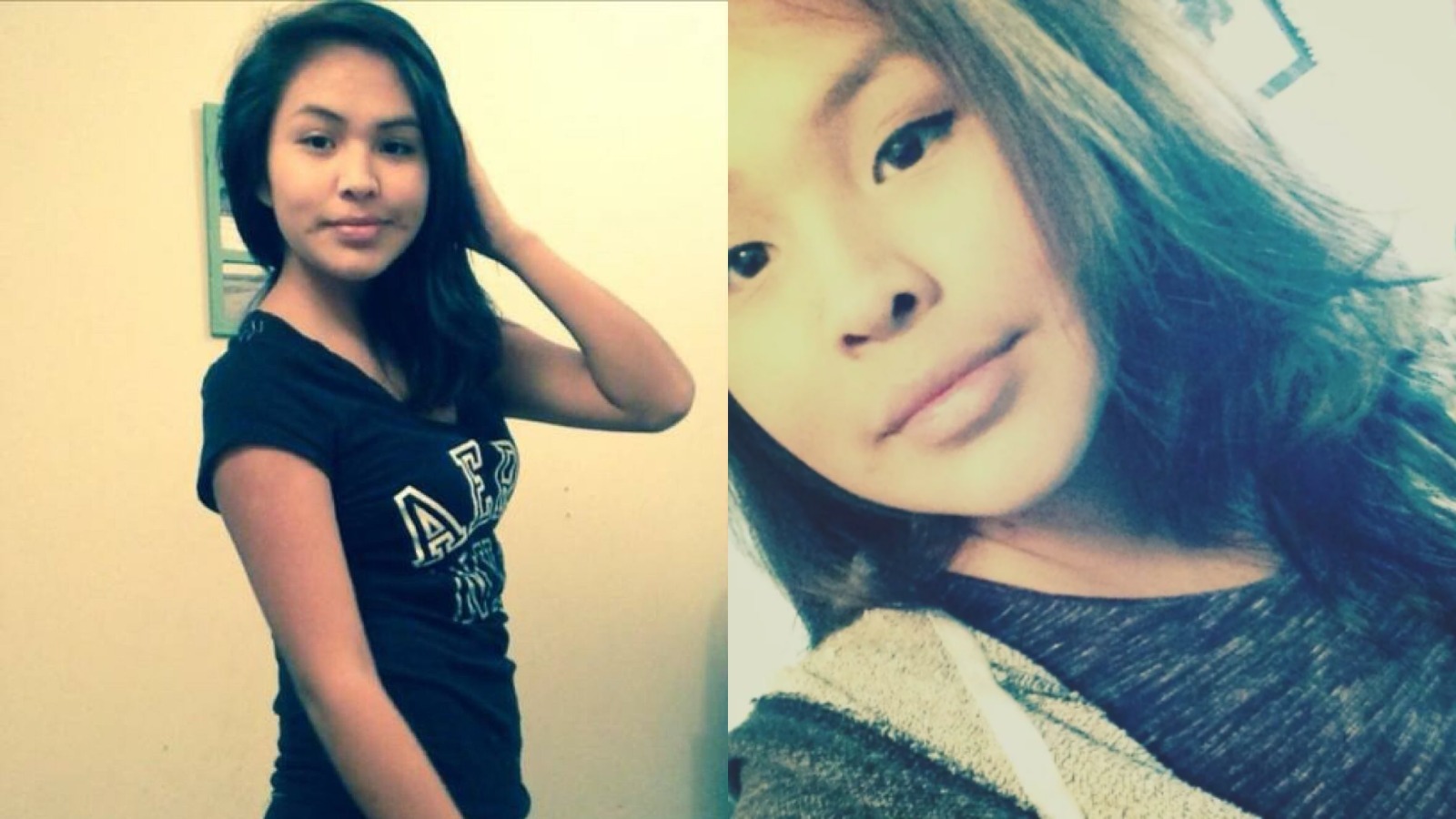

Families from across the country spoke to CBC, including the family of 18-year-old Jocelyn George, a young mother of two children, who died in 2016 after RCMP arrested and detained her twice in one day for being intoxicated.

George had been arrested and detained at the Port Alberni, B.C., RCMP detachment. A few hours later, she was released barefoot and left to find her own way home.

A coroner's inquest into the teen's death was held in June of this year. Such inquests are a mandatory court proceeding in B.C if someone dies in police custody.

The officer in charge of releasing George was called to testify and admitted that he made no effort to place her in the care of a family or friend.

Two hours later, she was back in the cells after friends called 911, saying she was acting strangely. She was delusional and her responses were delayed, an RCMP officer testified at the inquest.

She was held in custody for 12 hours, during which time she was not given any food. Several officers testified routine checks were missed and no one saw the guards check on her.

"What does it take to be treated as a human being?" George's uncle, Matthew Lucas, said in an interview with CBC. "She should have gone to the hospital."

When she still appeared intoxicated after 12 hours, she was taken to the local hospital and then airlifted to Victoria. She died that night of heart failure.

Dr. Jason Morin, a forensic pathologist who conducted the post-mortem exam on George, testified the cause of her death was drug-induced inflammation of the heart.

It was an acute case — not a chronic problem — due to the prolonged period of time she was in medical distress, he testified. Otherwise, the teen had a healthy heart.

"What they found in the inquest was … [the guards] never paid attention. They left her alone," Lucas said.

RCMP protocol says a person guarding an individual must seek immediate medical assistance if the person exhibits "any sign of medical distress."

The inquest into Jocelyn's death made several recommendations to the Mounties, including creating a policy to ensure food is offered to detainees, developing a policy when releasing minors, transporting persons to a health facility if their health status isn't clear and having on-call health-care professionals assess detainees in cells.

Charges against Halifax special constables

On June 15, 2016, Corey Rogers was a new father and on his way to meet his daughter, Hailie, for the first time at a Halifax hospital.

The 41-year-old had been drinking. Police were called when he was caught with a mug of liquor outside the hospital.

He was arrested, and after he allegedly spit at officers, a spit hood was placed over his head.

He was placed in a cell to sleep off his intoxication.

Security video indicates Rogers' last movements in his cell occurred at 11:41 p.m. The special constable is seen entering the cell and attempting to rouse Rogers nearly two hours later.

No one took the spit hood off and he was found lying face down in a cell, suffocated on his own vomit.

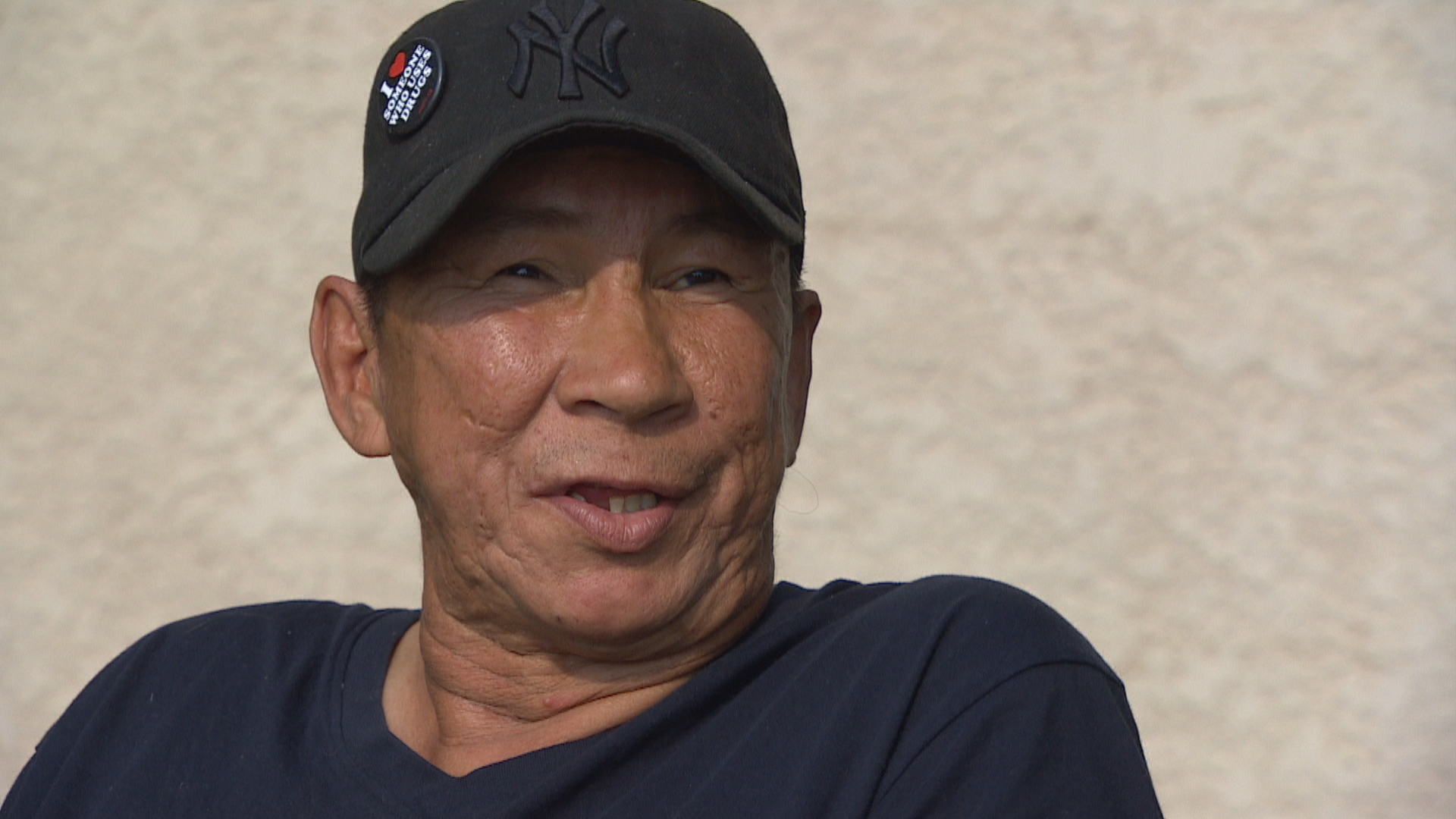

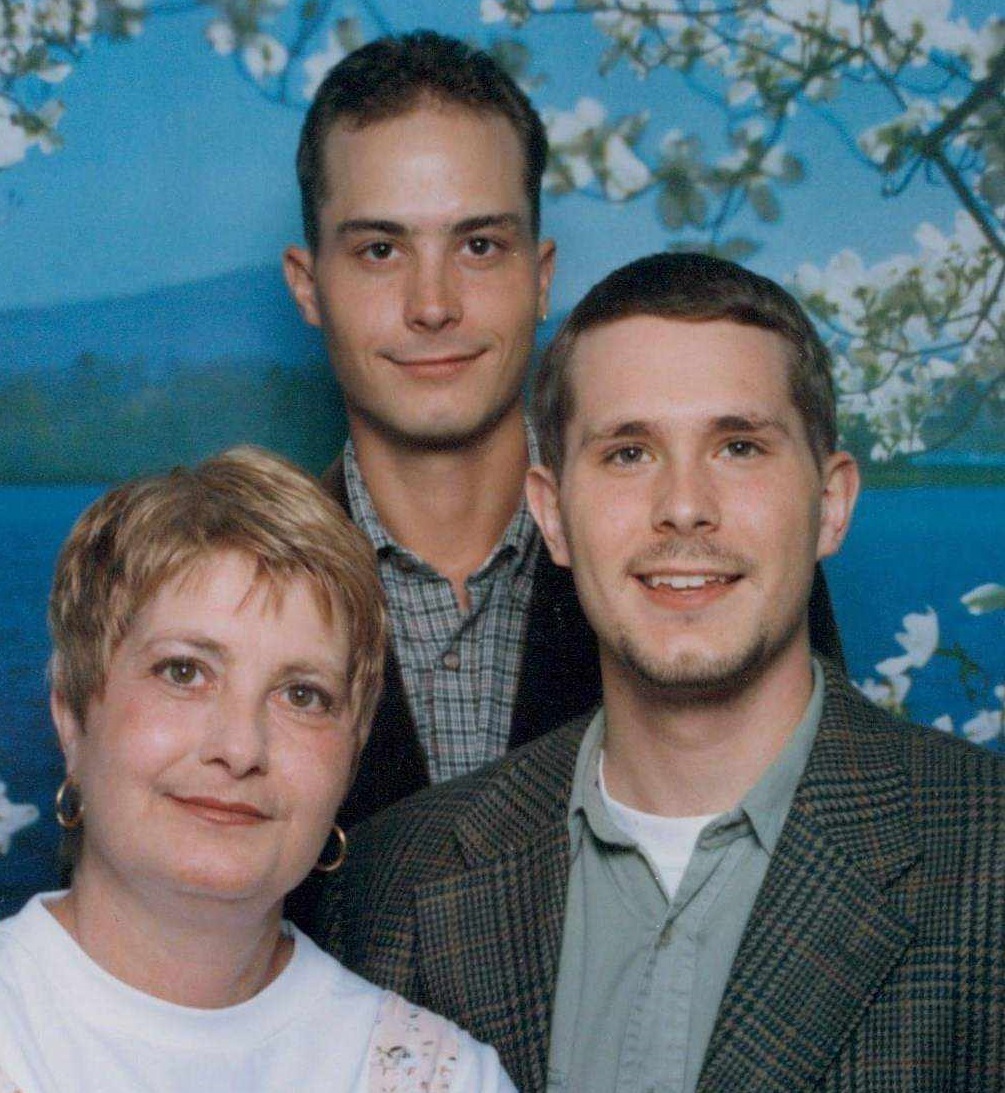

"The way they treated him was unconscionable," Jeannette Rogers said of her son. “Alcoholism is an illness that's not a crime and it certainly shouldn't be punishable by death.”

Nova Scotia's Department of Justice has a policy similar to the RCMP's — anyone in custody has to be checked on every 15 minutes.

After two civilian special constables were charged with criminal negligence causing death in Rogers's case, it was revealed the guards weren't following that policy.

Under oath, one of the special constables testified there were too many people to watch and guards were instructed to only do checks for high-risk detainees.

Jeanette Rogers lost her 41-year-old son Corey who died in a Halifax jail cell after being arrested for public intoxication. She says alcoholism is an illness, not a crime, and it shouldn't be punishable by death.

The special constables were convicted, but the decision was overturned on appeal. A new trial is scheduled for March 2022.

Security video of Corey's arrest played at the trial still haunts his family.

"The first time that we saw it, we were so affected and disturbed by it that we told them to turn it off," said Corey's brother, Collin Rogers.

"It was like watching snuff."

It was unclear what internal discipline the Halifax Regional Police officers who arrested Rogers received, so Jeannette Rogers asked the Nova Scotia Police Review Board to impose stronger disciplinary measures.

After months of waiting and days of testimony, the board's decision was released on Nov. 29 — finding the officers committed multiple disciplinary defaults, including discreditable conduct.

The penalties for the officers will be announced at a later date.

A spokesperson for Halifax Regional Police said the service does not typically comment on the rulings of Nova Scotia's police review board.

"We have continued to make improvements to processes related to our prisoner care facilities, and take this responsibility very seriously," wrote Const. John MacLeod.

He said because of the pending new trial in Corey Rogers's case, Halifax police cannot comment further.

Jeannette Rogers has mixed feelings about the police board's decision, noting there were several instances where it found no defaults, and criminal charges are not being pursued.

She wonders what would have happened if officers had taken her son to her house, or if Halifax had a sobering facility like those in many other municipalities.

No sobering centres in small communities

Sobering centres, or detox centres, are where someone who is intoxicated should be placed, said David Thorne, a retired deputy chief with the Winnipeg Police Service.

Legislation is needed to allow police to legally detain someone if, for example, officers come across someone intoxicated and unconscious in freezing weather, Thorne said.

But many communities don't have sobering centres, so a police station holding cell becomes the only option, he said.

"We end up using a law enforcement solution to a health problem and that's inappropriate."

However, as RCMP noted in a prepared statement, their detachments are often the only 24/7 service available.

In urban centres like Winnipeg, for example, police are able to take someone to the Main Street Project. The non-profit offers services for vulnerable people and can house intoxicated people in its protective care facility (such facilities are commonly known as "sobering centres").

In total, there are at least 12 of these centres across Canada, with plans for others in smaller municipalities like Prince George, B.C., or Thompson, Man., next year.

The centres are open 24/7 and staffed with health-care workers. Individuals are constantly monitored by people trained to deal with intoxicated persons.

Since Corey Rogers's death, there have been calls for a sobering centre in Halifax.

But for Collin Rogers, it is years too late.

"I think the biggest tragedy is that they went to go pick up somebody who was drunk, and he died," he said.

"It was that simple."