August 17, 2018

Roy Rushton spent three-quarters of his 100 years with both a bullet and a piece of shrapnel in his body — souvenirs from the Second World War that the paratrooper wouldn't let keep him from serving later in Korea.

He lived life with grit.

The Nova Scotia man died June 17, but the stories of his many adventures are being shared Saturday at a memorial service in Pictou, N.S.

He's been remembered by his fellow soldiers as a man they looked up to for his demeanour, experience, judgment and calming presence.

Paratrooper's 1st jump

Rushton's battle experience began on the evening of June 5, 1944, when he leapt from a plane the night before D-Day. With that jump, he became one of 450 paratroopers who landed behind enemy lines in northern France to try to secure positions before the Allied forces arrived.

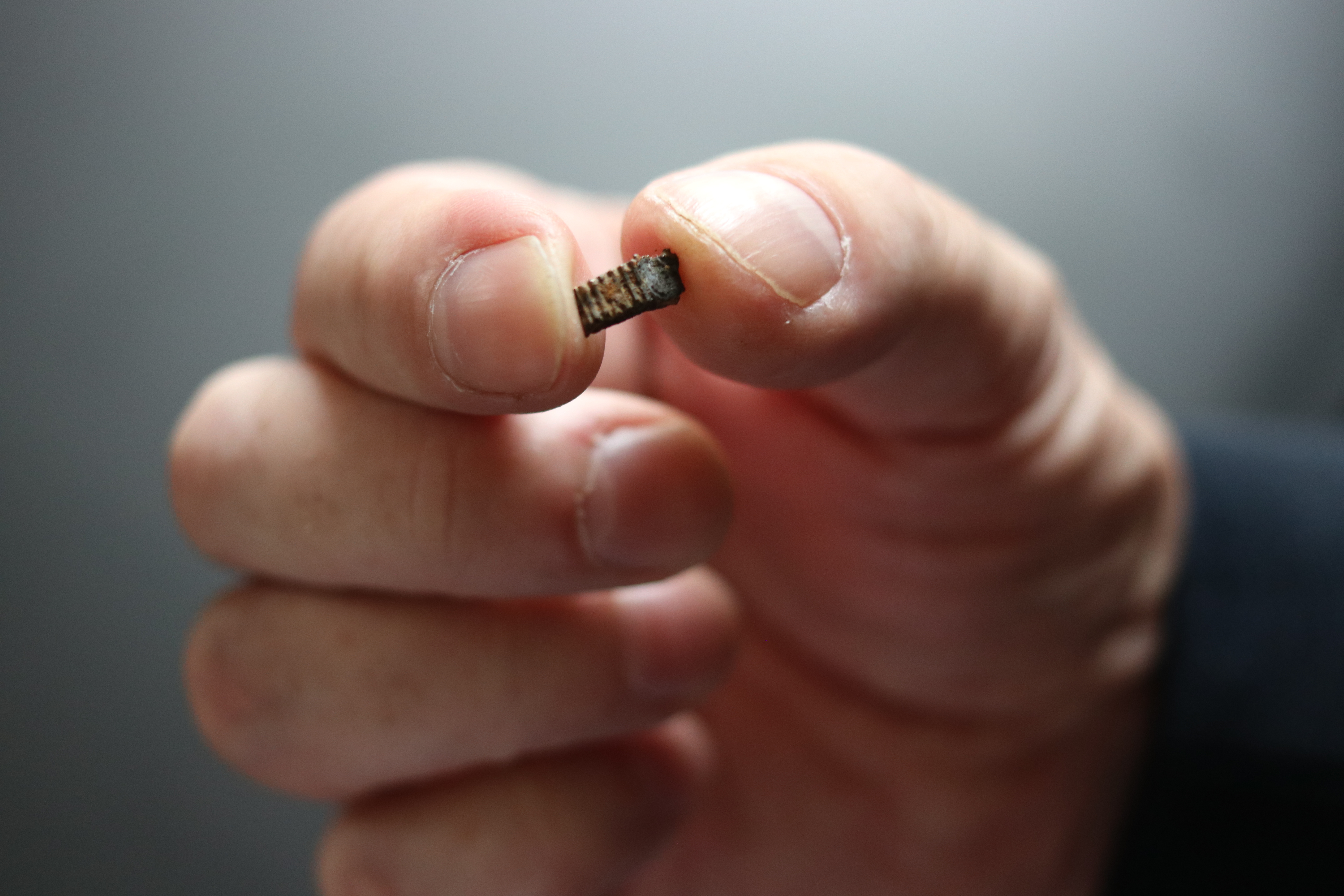

Rushton hit the ground in Varaville. Hours later, he would be struck by shrapnel while running along a hedge. The piece of metal would remain in his body for the next 74 years; despite the pain it caused, the shrapnel sat too close to a nerve to be removed.

His family had it taken out after he died.

Rushton's Second World War service came to an end on March 24, 1945, just months after he survived the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. Although the Pictou County man lived through a battle that saw 75,000 Allied casualties, he was shot in the thigh after he crossed the Rhine River and landed in western Germany.

He was 27.

The bullet would never be removed because doctors told him there could be complications.

Before the war, Rushton worked on his family's farm. Afterward, he bought and ran a store in Salt Springs, N.S.

But like the metal in his body, soldiering remained in Rushton's blood. When the Korean War broke out, he handed the store's keys over to his mother.

A return to battle

Age and his injuries, however, made a return to the battlefield more painful, his friend says.

"The physical strain, no doubt, must have been a great deal more on guys in their 30s, particularly guys who had been wounded in the leg and were carrying a bullet around with them," said Vincent Courtenay, 84, a fellow Korean war veteran who befriended Rushton later in life.

Robert Rushton, one of the man's four sons, recalls how the injury affected his father.

"In particular, when he was climbing the mountains in Kapyong in Korea, he found that it bothered him — although he did continue on to do his job as a soldier."

But it wasn't in Rushton's nature to complain or let on about the injury to others.

His former brother-in-arms, Bernie Cote, 89, was unaware of the bullet lodged in Rushton's leg; Cote said he only learned about it through speaking to CBC News. Instead, what he remembers of the soldier he served alongside in 1951 was his laid-back attitude and the way in which he inspired the men around him.

He was a "real guy from down East," Cote said. "And all the guys in the platoon thought the world of him."

Rushton's past wartime experience made him a role model for those serving alongside him, Cote said.

"When you get somebody that knows something and you don't know nothing, they were like a father figure to you," said Cote, who was then 22 to Rushton's 33 years of age.

"You felt safe with them."

An example of this came when Rushton's platoon worked to capture Hill 532, a mountainous piece of terrain named for the fact it was 532 metres above sea level.

Their platoon led the offensive and Rushton took charge after his platoon officer was injured at the start of the mission, says Courtenay, who wrote about the offensive in the book Rideau Hall, which follows the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry from 1950 to 1951.

He says Rushton and his comrades fought all day through ankle-deep snow to reach the heavily defended summit before the Pictou County soldier made a critical decision.

Becoming a leader

"His platoon had taken many casualties — they were virtually out of ammunition — and he asked the captain in charge of the company to call off the action," Courtenay says. "If they took the position, because it was close to nightfall, they were going to get counterattacked and would just be wiped out."

The commander agreed.

The next morning, the forces took Hill 532 with little opposition.

Courtenay credits Rushton's decision with saving numerous lives. And while Rushton started the battle as a corporal, he finished as a sergeant.

Rushton's service in Korea came to an end in 1951 because of a hearing problem, his son says.

Once he was discharged, Rushton returned to running his store for several years, and he and his wife Margaret raised four sons together, two of whom would join the military.

Rushton never abandoned military life. He joined different regiments and later served as an instructor with the Halifax Rifles, Pictou Highlanders and Royal Hamilton Light Infantry.

He also worked as a commissionaire and later started his own small appliance repair business.

Even in retirement, Rushton kept his sense of adventure. He exercised it by travelling and in his decision to jump out of an airplane at 65, his son says.

As the jump unfolded, Rushton looked to be in danger of landing in a water reservoir.

"He started playing with the cords and he ended up slamming into the side of the hill, just below the airport," his son recalls. "He hurt his knee — he couldn't walk on it for about three weeks — but that's the type of adventurous man he was. He would do things out of the blue, just like that."

Rushton became involved with several veterans' groups. And he returned to Korea in 2003 as part of a trip to Kapyong organized by Veterans Affairs Canada.

His stories always focused on the funny moments he had overseas and the good people who served at his side. He never discussed the horrors of war, his son says, but his actions sometimes hinted at the pain to which he'd been a witness.

When he was a young boy, Robert Rushton said he'd sometimes come home to find his father listening to Hank Williams's rendition of I'll Sail My Ship Alone, with tears in his eyes.

"As the years went on and as I became a soldier, it became quite clear to me exactly what he was doing," Rushton's son said.

"Reminiscing."