July 18, 2019

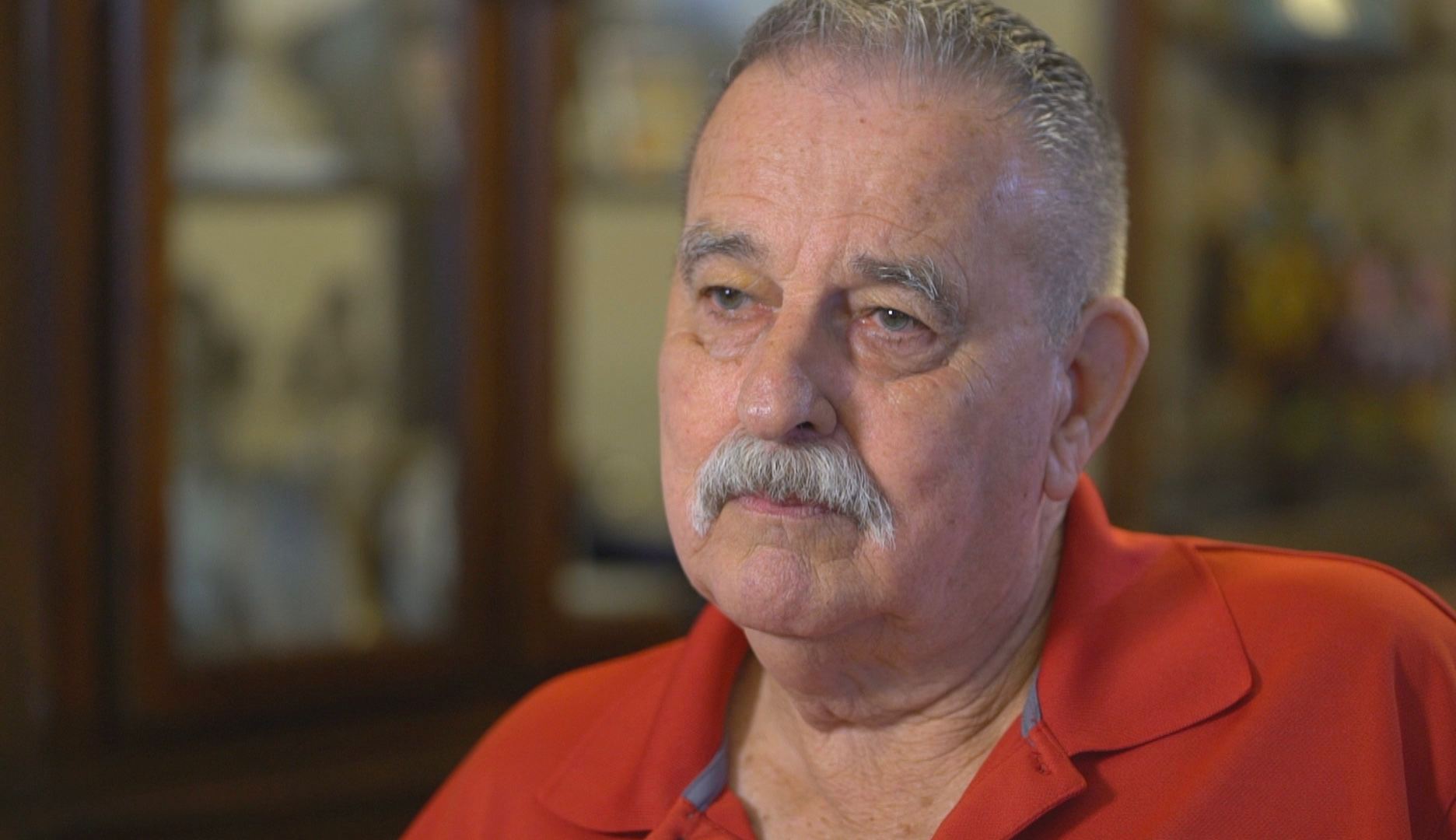

A 70-year-old Florida man says he is the son of New Brunswick's longest-serving premier, the late Richard Hatfield, who was sometimes described as "flamboyant" and a "life-long bachelor."

“I would still have loved him as my father,” said John Hall from his home in Brooksville, north of Tampa.

Retired from the U.S. Army in 1989 and now a part-time realtor, Hall said he has stitched together his story using registered documents from New Brunswick's post-adoption services, his own DNA and contacts with people living near Hartland, the small western New Brunswick town where Hatfield grew up.

He’s convinced that a young Hatfield, around the time he graduated from Hartland High School in 1948, must have been romantically involved with a classmate named Izetta "Toodie" McKeil.

Hall said he believes they maintained a loving connection that lasted until their deaths in 1991, when both succumbed to cancer, Hatfield at age 60 and McKeil at age 61.

The unwed mother

Hall was born May 16, 1949, to a 19-year-old woman at the Evangeline Maternity Hospital for unmarried mothers and their babies. The Saint John-based facility was run by the Salvation Army.

"Unfortunately, there was no physical description of your birth mother on file, nor any mention of her education, health history, interests or aptitudes," wrote Anne Doyle, a social worker with the New Brunswick government, in a letter to Hall dated Aug. 3, 2001.

Post-adoption disclosure policies at that time blocked adoptees’ access to the names of their registered birth parents. Those names were sealed once an adoption was formalized and the birth certificate would show only the names of the adoptive parents.

"Your birth father was named on the file but our legislation does not permit me to disclose his identity to you," Doyle further explained.

"Unfortunately, there was no other information gathered about him, other than he was also from New Brunswick and that he has 'failed to assume any responsibility.’"

Who found Toodie McKeil?

Hall said he never questioned his adoption to Janet and Earl Hall until after they passed away in the 1980s.

Hall moved with his family from Coldstream N.B. to Houlton, Maine, when he was in Grade 4.

“I had a loving home. They were loving parents,” he said.

However, before she died, Hall’s adoptive mother told him that his birth mother’s last name was McKeil and that she lived in the Waterville area.

When Hall was ready to step up his search, he turned to Parent Finders New Brunswick, a non-profit group that’s operated by Marie Crouse, who lives in Wakefield, south of Hartland.

Crouse started a file on Hall and with the help of her volunteers, concluded that Hall’s mother must have been Izetta “Toodie” McKeil, the only daughter of the McKeil family, who lived on a hog farm near Hartland and later moved into town. McKeil was the right age and lived in the right place.

“She was the only one that fit,” said Crouse.

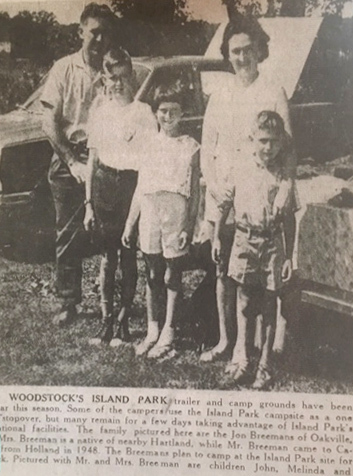

By 2010, Hall had tracked down McKeil’s son, Jan van den Breeman, who was living in Ontario.

Both gave their written consent to post-adoption services to tell them if they were siblings. The answer came back, yes. For Hall, that matter was solved.

'Every time she'd see him on TV, she'd say, ‘Oh, there's Dickie. There's Dickie. He's a big shot. He’s a big shot now.’’

McKeil moved to Ontario in 1949 almost as soon as she was allowed to leave Saint John.

According to post-adoption services in that letter to Hall in 2001, his birth mother had to stay at the Evangeline home until late September because her baby had been suffering from pneumonia and then gastro-enteritis.

Hall learned that his birth mother had also been referred by the Evangeline home to the “local Children’s Aid Society because she wanted to make adoption plans for you.”

After moving to Ontario, McKeil was married within a year and went on to have three children, including Jan van den Breeman. There was also her daughter, Belinda van den Breeman Hoffman and Dougie van den Breeman, who died in 2006.

In the 1960s, the family travelled to New Brunswick for two or three summer vacations.

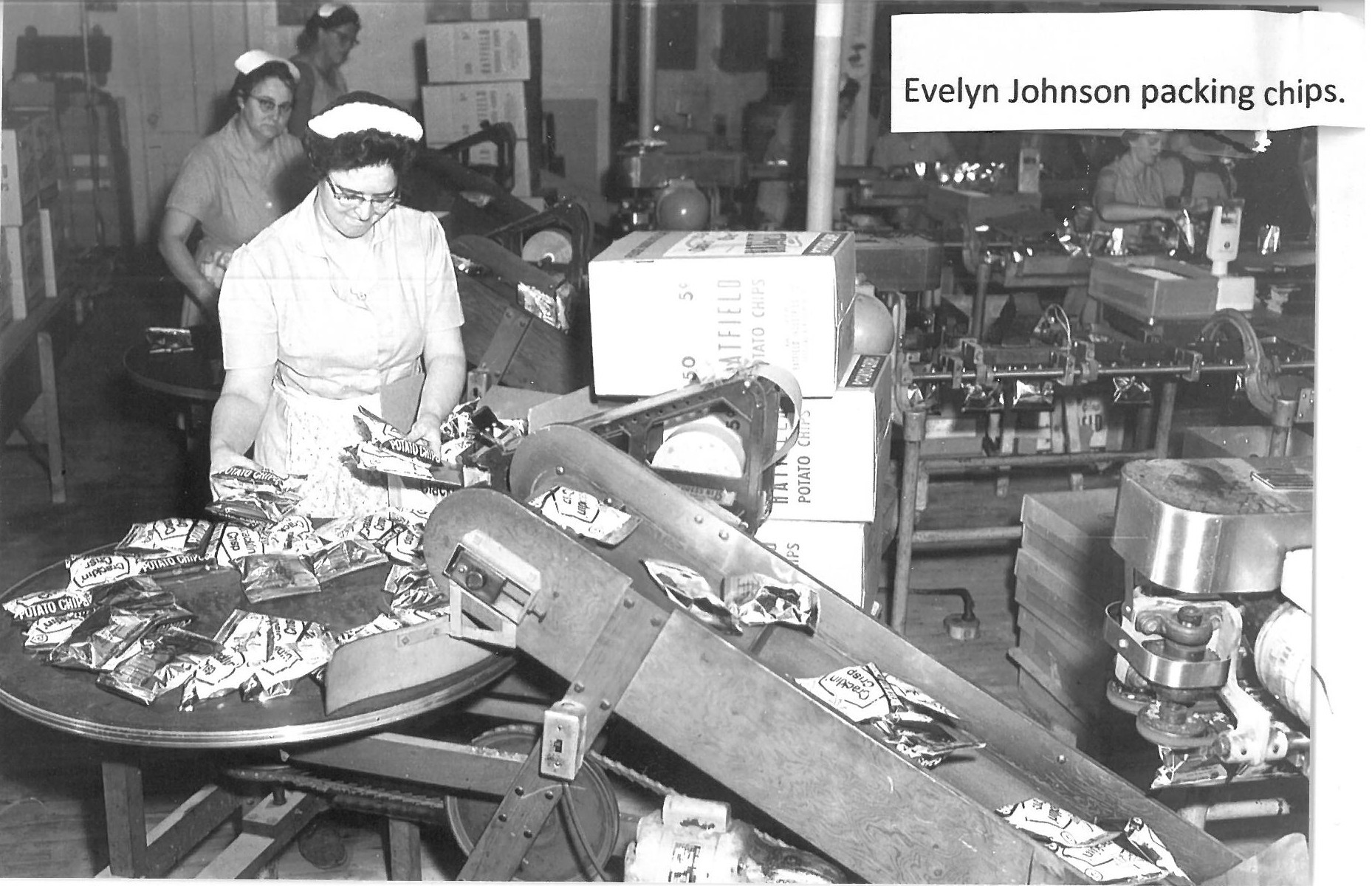

Just before the start of one drive home, Hoffman said in an interview she remembered her mother insisting on “saying good-bye to Dickie” at the Hatfield potato chip plant where Richard Hatfield worked in sales before he went into politics.

Hoffman has vivid memories from that day. She called it a “stinking hot day” and said it felt like they waited “forever” in the back of the family’s 1963 Chevrolet Biscayne parked in the potato chip factory parking lot.

"It was gold. The big car. Full size. I'm a car buff," said Hoffman explaining why she feels so certain of these details.

"We sat outside waiting for her to come out. It was like a lifetime sweating in that hot car,” she said. “Then she came out with three big bags of potato chips just to shut us up, I think."

It used to be possible to buy large paper bags full of loose potato chips hot off the cooker for about 50 cents.

Hoffman also recalled how her mother paid particular attention to the New Brunswick premier if he appeared on the news.

“Every time she'd see him on TV, she'd say, ‘Oh, there's Dickie. There's Dickie. He's a big shot. He’s a big shot now,’” she said.

The 1st meeting

Jan van den Breeman also said he remembers the day he sat with his siblings in the back seat of that car, eating those chips.

He met Hall for the first time in 2012.

Van den Breeman said his mother never spoke of having a child before she got married. He said it wouldn’t have gone over well with his strict father, who died in 2014.

Belinda Hoffman said finding Hall has also caused her to reconsider a comment that her mother used to make.

"When I was going on a date, she would tell me, ‘Keep that aspirin between your knees. Don’t let what happened to me, happen to you,’” she said.

“I think she was talking about herself, without telling me she had a son out of wedlock.”

McKeil’s funeral

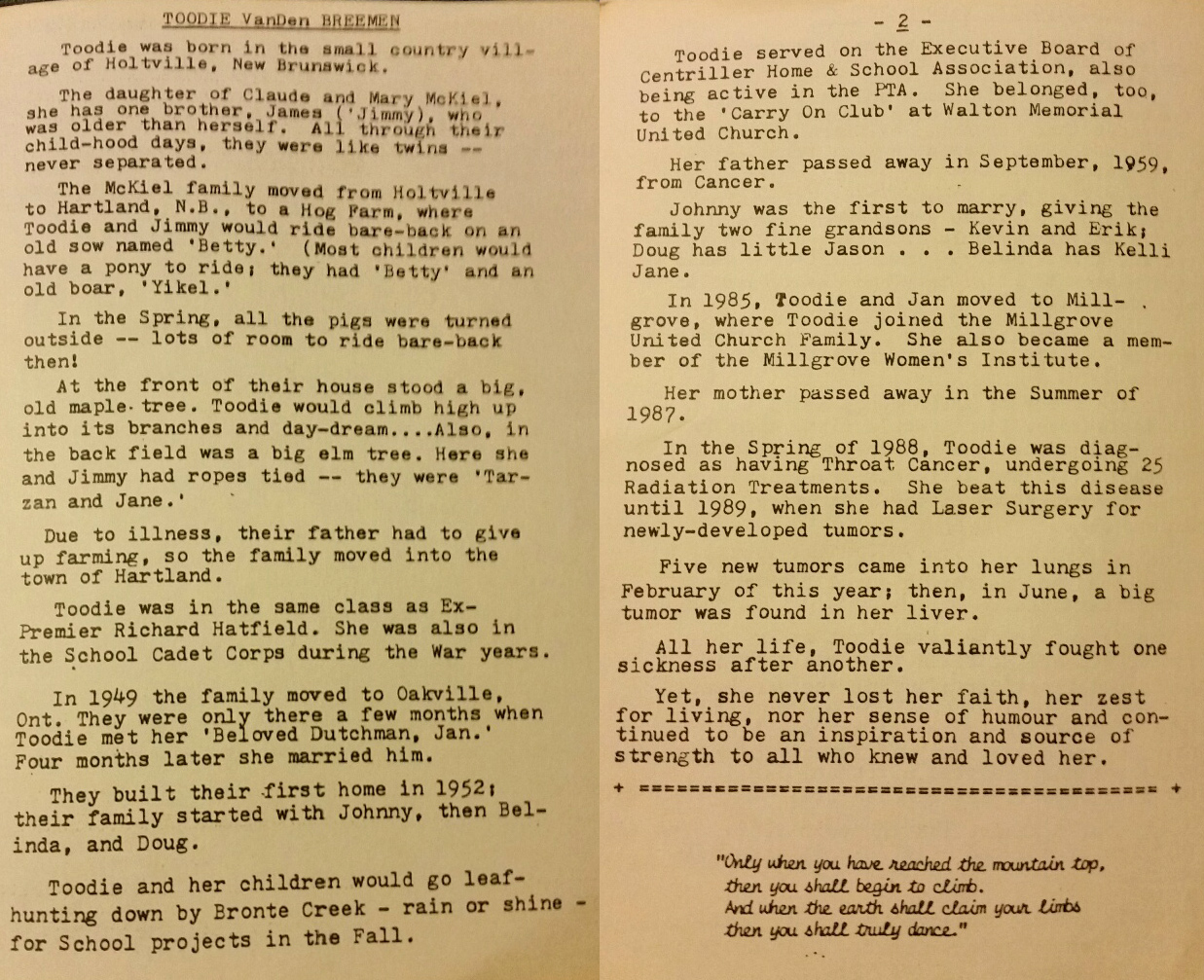

McKeil’s funeral service spoke of her valiant fight with one sickness after another, including throat cancer, which was diagnosed in 1988.

Her son, Jan, said she prepared her own funeral service which was held at Millgrove United Church, in Millgrove, Ont, after she passed away on June 6, 1991.

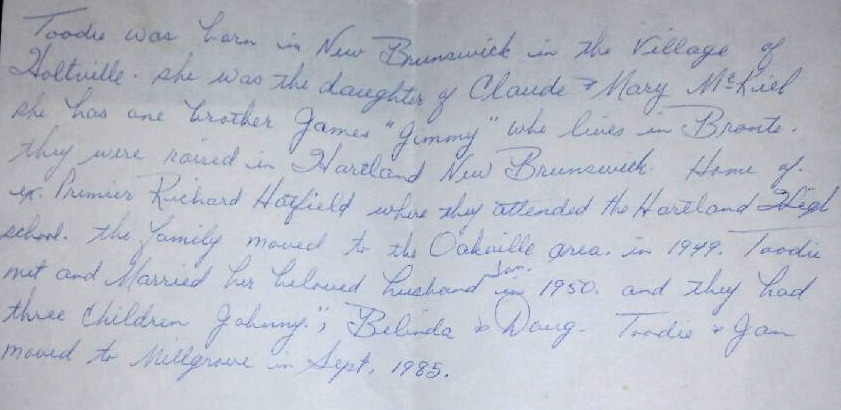

In her hand-written eulogy, McKeil notes that she and her brother James were “raised in Hartland, New Brunswick home of the ex. [sic] premier Richard Hatfield where they attended the Hartland High School.”

“She and Richard chummed around a lot,” said van den Breeman. "She said they played around on the farm and always kidded about how she would make him hold the electric fence wire and get shocked."

The funeral notes also make mention of McKeil living on a hog farm near Hartland, where she and her brother would ride bare-back on an old sow named Betty.

Again, it’s mentioned that, “Toodie was in the same class as ex-premier Richard Hatfield.”

There is no hint of any pregnancy in New Brunswick or giving up a child.

Instead, the eulogy skipped to her move to Oakville in 1949.

“They were only there a few months when Toodie met her beloved Dutchman, Jan. Four months later, she married him.”

DNA puzzle

Janet May, Hall's 48-year-old daughter, said she's 90 per cent certain that Richard Hatfield is her biological grandfather.

She got her father to submit a saliva DNA sample to Ancestry.com in 2016 and May has been working since that time to fill in the family tree.

May has devoted many hours to solving the unknown spaces in her family tree and she believes her answer is evidence-based.

She said she found a DNA connection between her father and Richard Hatfield's niece, Emily Clark Dingle, the daughter of Richard Hatfield’s sister Rheta.

Clarke Dingle, who declined to be interviewed, comes up as a possible fourth cousin to John Hall, according to May.

May said she's also found three connections on Hatfield's mother's side.

May said she did consider the possibility that her father’s paternity might be linked to other members of the Hatfield family, such as Richard Hatfield's two older brothers, or even his father, the successful potato broker, Heber Hatfield. But she said she can’t see it.

“There’s no resemblance to any of them like there is to Richard,” said May.

It’s an emotional pursuit for May, but she said she tries to park her feelings and follow the facts.

"I'm looking to give my dad some closure. I'm looking to give him some family,” said May, pausing for a few seconds to compose herself.

“I’m not going to put something there, that’s not there and just destroy all these peoples’ lives. That’s not what I’m looking to do.

"I need to look at this with my head and not my heart."

Timeline: A Florida man's 20-year quest to find his father leads him to Richard Hatfield.

Digging through old photos

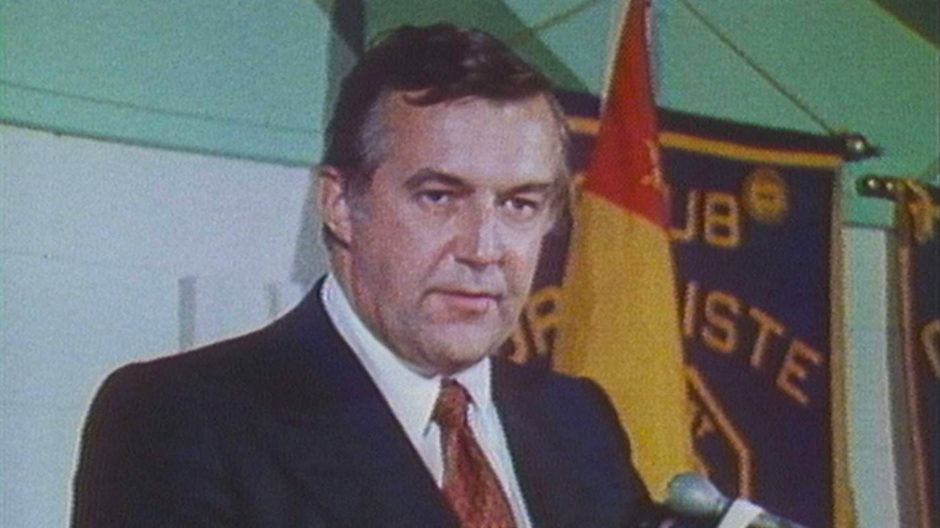

Old photos of Richard Hatfield aren’t hard to find. He led a public life from the time he entered politics as a Member of the Legislative Assembly in 1961 and most notably, when he served as premier of New Brunswick from 1970 until his defeat in 1987.

He also served as a senator from 1990 until his death, the following year.

But of all the photos May saw online, one in particular, blew her away, she said.

She found it on Beth Hatfield Barton’s online family tree on Ancestry.com. She was so struck by its likeness to her father, she sent a copy to her mother, who had been married to John Hall for 20 years before they divorced.

"She said to me, 'Jan, why are you sending me photos of your father. I know what your father looks like. It's a picture of your father, in an ugly suit, I don't know why you're sending me this."

"I said to mom, 'No mom, look at the date on the side of the picture, April 1968. Dad would have only been 19 that year. The man in that picture is in his 40s. That's Richard Hatfield.'"

John Hall said comparing the photos also made him a believer.

"Look at the pictures," he said. "You see Richard, you see me."

Hatfields reluctant to be interviewed

Richard Hatfield never married.

However, Hatfield’s two older brothers and two older sisters, now deceased, did have children and altogether the former premier ended up with 19 nieces and nephews.

“John would be the 20th,” said 63-year-old Deborah Hatfield, daughter of Richard’s brother Harold.

CBC News also contacted nieces Susan Hatfield Everett and Emily Clark Dingle because Hall said he’d also been in contact with them.

Everett declined to be interviewed on the record. Dingle said any family statement would be coming from her cousin, Bruce Hatfield.

Bruce Hatfield also declined to be interviewed on the record.

Deborah Hatfield said she doesn’t know for certain if Hall is Hatfield’s son but she said she is open to the possibility.

'Everybody deserves to know the truth.'

She’s in regular contact with Hall, mainly through Facebook Messenger, and if he comes to New Brunswick in August, as he said he is planning, she intends to meet him.

“I look forward to it,” she said.

There are some in the family who don’t think it’s possible at all, said Deborah.

She said she has asked around and hasn’t found anybody who can link Richard Hatfield to McKeil or ever heard of a pregnancy or a child that resulted from such a relationship.

Still, she doesn’t discount Hall’s effort to find his roots or his conviction about who he is.

“Everybody deserves to know the truth,” she said.

'Adventures with Uncle Dick'

Hall said his greatest regret is that he never got a chance to meet McKeil or Hatfield before they died.

Of all the reading and research he’s done, Hall said he has nothing but the highest regard for Hatfield and views him as a visionary and a man before his time.

Many New Brunswickers are familiar with Hatfield’s official biography, how he served as premier for 17 years, how he was involved in constitutional negotiations in the 1980s or how his government tried to create an auto industry in the province by producing Bricklins.

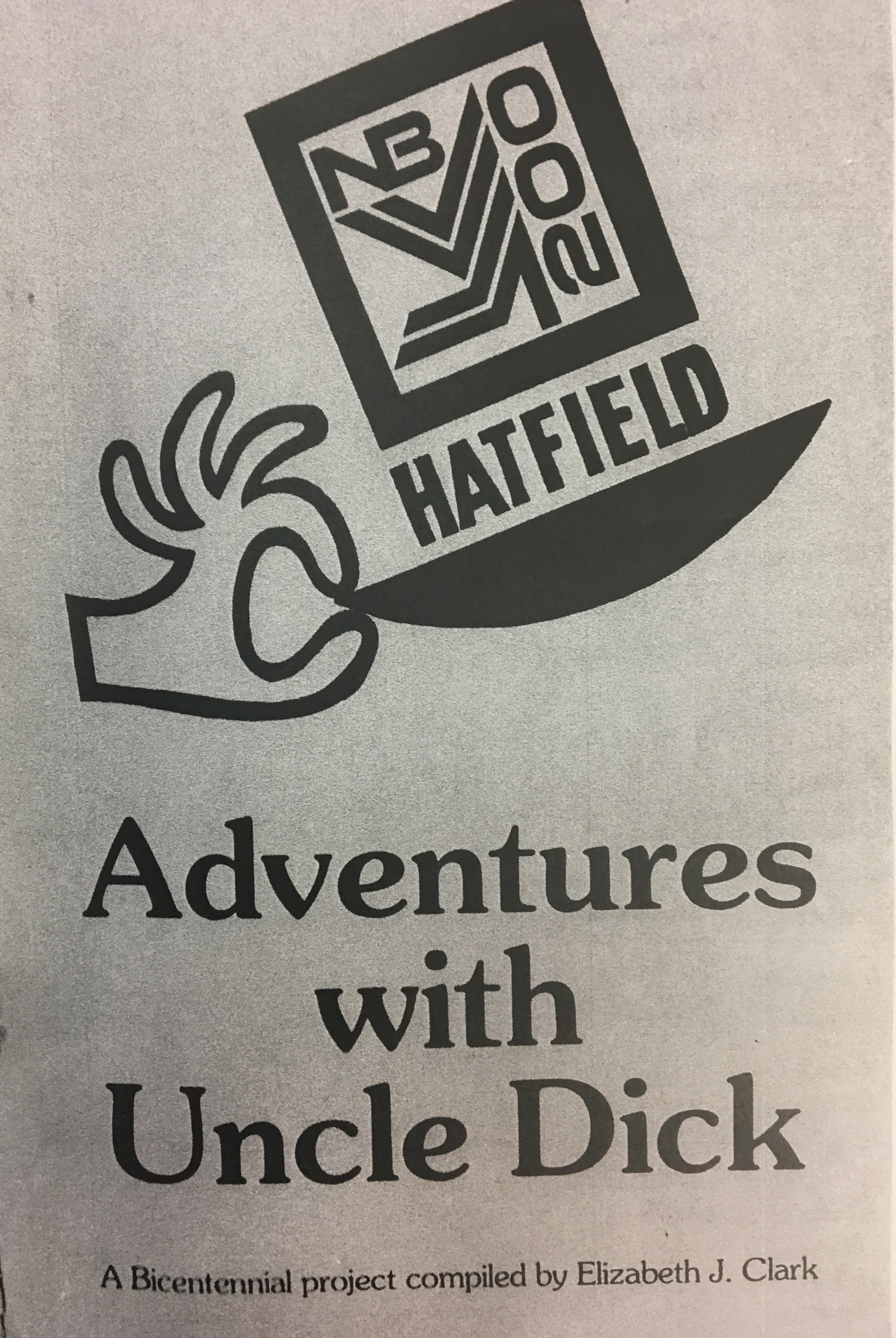

But Hall said he thinks Hatfield would have been a loving and generous father, based in part, on a booklet he was sent by Hatfield’s niece, Susan Hatfield Everett.

“Adventures with Uncle Dick” is a compilation of first hand accounts from Hatfield’s nieces and nephews that details how he doted on them with gifts and attention and took them on trips and introduced them to famous people.

He was the uncle who dressed up for Halloween as a headless man, with a ketchup-bloodied collar where his neck should be.

“This book is for you, Uncle Dick, with our many thanks,” wrote Elizabeth Clark in the introduction.

“I have always been proud to have an Uncle like Uncle Richard,” wrote Wendy Everett.

Hall said he hopes to have his cousins accept him into the family.

“If they think I’m after something … well, there’s no money there,” said Hall.

“Maybe there used to be, but not anymore,” he said.

“I’m just after the truth.”

Waiting for his answer

Hall recently applied to the New Brunswick government’s post-adoption services branch for his statement of original registration of birth.

It’s a fairly new option for adoptees who have reached the age of majority.

As of April 1, 2018, changes to New Brunswick legislation now allow grown adoptees to ask for these statements, which identify the name of the birth mother and her place of birth.

However, the new rules do not guarantee the birth father’s name will be released in every case.

If the father was unknown or did not sign the registration, his name will not appear on the statement of registration.

Even if the father was mentioned in the file by the mother or a social worker or some other source, if he did not sign the registration, his name may not appear.

When Hall receives his documents in the mail, he said he doesn’t expect to see any father listed at all.

“There is a name, but they will not release it because it’s not on the birth certificate so that’s not going to happen,” he said.

He hopes that when his story comes out, somebody in the Hatfield clan who knows something will say something.

“Eighteen years, 20 years I’ve been looking,” said Hall.

“At this point, you’d have to prove that Richard Hatfield was not my father.”