September 18, 2021

Warning: This story contains graphic details.

As the Cold War lurched toward its demise in the mid-1980s, leftists and union organizers in Guatemala started to vanish ― students, professors, a doctor, a poet.

No charges were ever laid against these purported "enemies of the state," as the government of this Central American country called them. No arrest warrants were ever issued. But people in the labour movement came to fear the windowless white vans driven by death squads with links to military and police forces — and the young men and women forced into them at gunpoint were rarely seen again.

Fearing for their lives, members of many targeted families fled to other countries, including Canada.

Wendy Mendez's family was among them, arriving in Vancouver in 1985 as political refugees after the disappearance of her mother, who worked for a university newspaper and promoted organized labour.

She has never been found.

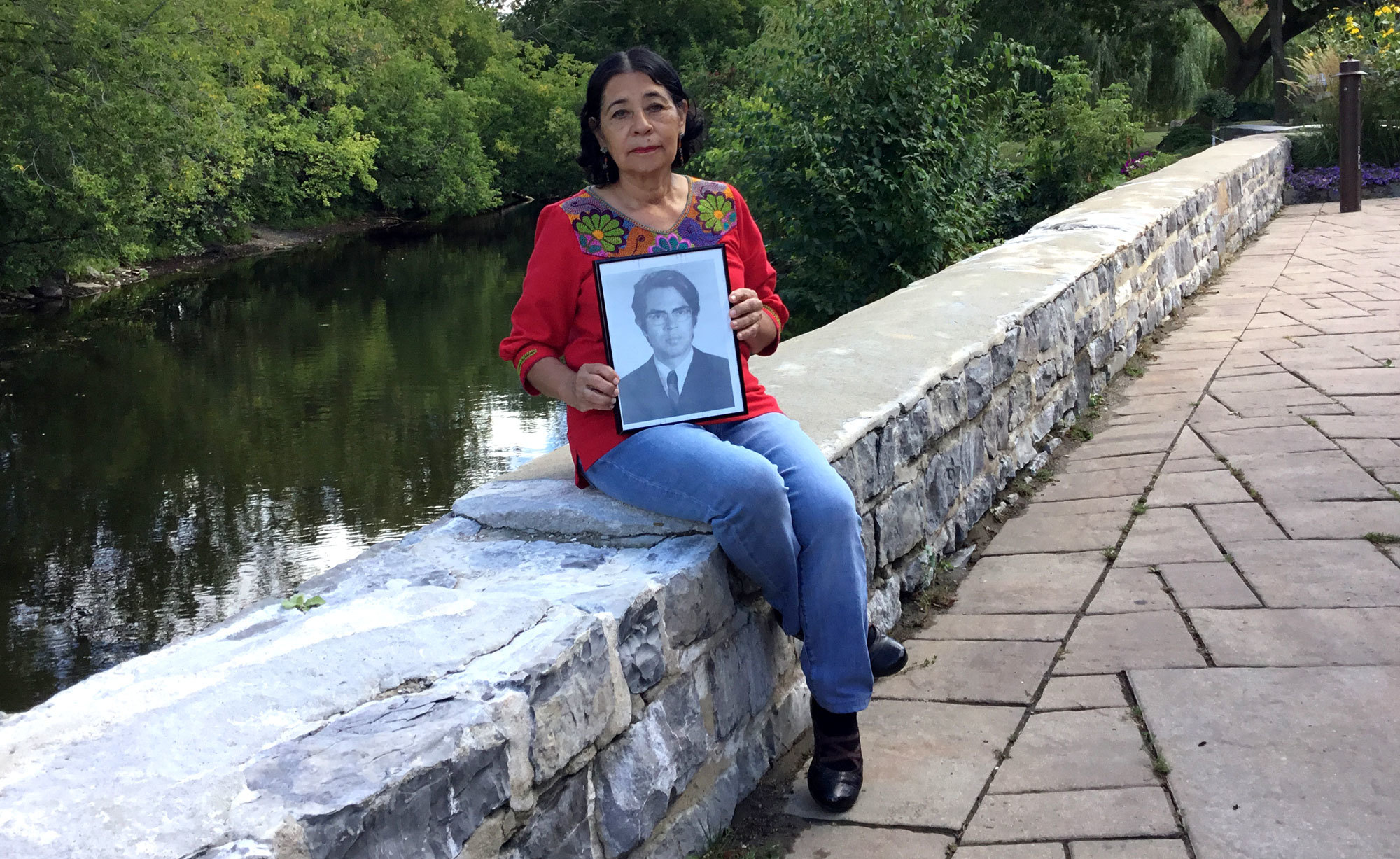

"The crime continues every day," says Mendez (photo above), 37 years later. "The anguish and torture of not knowing where your family members are is part of that crime. So the forced disappearance is not just to take [the person] out of their family, their job, their neighbourhood or their community. It also has to do with the effect on the people around the person who has disappeared … the ripple effect."

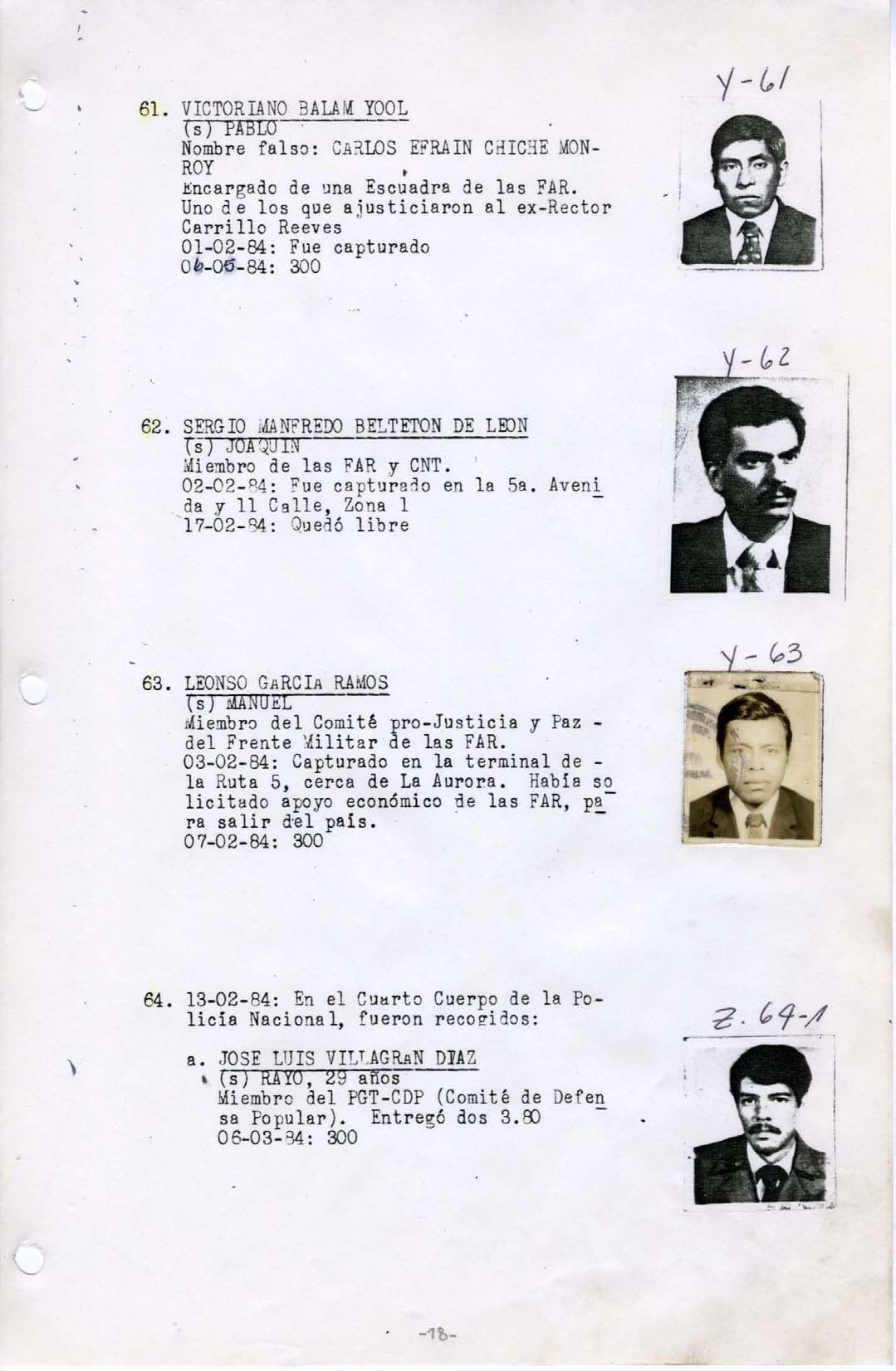

The code '300' at the end of the entries is understood to mean the person was executed, although the location of their remains is unknown.

According to the 2016 Canadian census, 17,275 people listed Guatemala as their birthplace, with 6,665 saying they arrived in the 1980s, a higher number than any decade since.

At the time, the Guatemalan army, supported by U.S. military aid, said it was fighting terrorists bent on a Communist overthrow. Government opponents said they were merely struggling to provide more rights to impoverished Mayan peasants being squeezed off the land by fruit growers and coffee conglomerates, or employed by those same companies for low wages.

The civil war, which lasted from 1960 to 1996, resulted in the deaths of about 200,000 citizens — mostly Mayan people in mountainous villages accused of harbouring guerrillas — including some 40,000 disappeared activists.

In 1999, families of the disappeared received the first evidence their loved ones had been captured, likely tortured and then killed, when the so-called Military Diary was leaked to researchers at the Washington, D.C.-based National Security Archive, a repository of declassified government documents from around the world.

The Military Diary is a disturbing catalogue of 183 entries containing photos, political party and labour connections of mostly young activists, along with the date and location of their capture. The code "300" at the end of entries is understood to mean they were executed, although the location of their remains is unknown.

In June of this year, a judge ruled that 12 former members of the Guatemalan military will be tried in court on charges connected to the diary, including torture, murder and forced disappearance. The trial will start to hear evidence in a Guatemala City courtroom on Sept. 21, amid an ongoing campaign by army veterans and some politicians to issue a sweeping amnesty for crimes committed during the war.

It's part of a long journey for a country trying to mend the deep divisions in its society. Since a peace accord was signed in 1996, only a few dozen former military officers have been jailed.

"We're all clear, all the families of the Military Diary, that we're not seeking vengeance. We're seeking justice," said Annabella Jiménez, who escaped to Canada in 1983 with her two-year-old son after her husband's disappearance, and now lives in Montreal.

"[We want] a just punishment to reach a stage of reconciliation and peace," she said. But above all, the families want to know the ultimate fate of their loved ones.

A mother and daughter abducted

Even as a young child, Wendy Mendez knew when to keep quiet. As a girl in Guatemala City, she'd seen a decapitated body on a sidewalk through the window of her school bus, seemingly ignored by people on the street who dared not go near it. No one inside the bus said a word about it.

"I remember my brain couldn't wrap itself around that. I was taught at home to not talk about these things, because it could be dangerous," said Mendez, now 47 and a human rights advocate and public educator. "It could generate violence against you, just talking about it."

Her father, a professor at San Carlos University, and her mother, who worked at the student newspaper, were both members of the Guatemalan Workers Party (PGT). And in the early ‘80s, that alone was enough to be labelled enemies of the state.

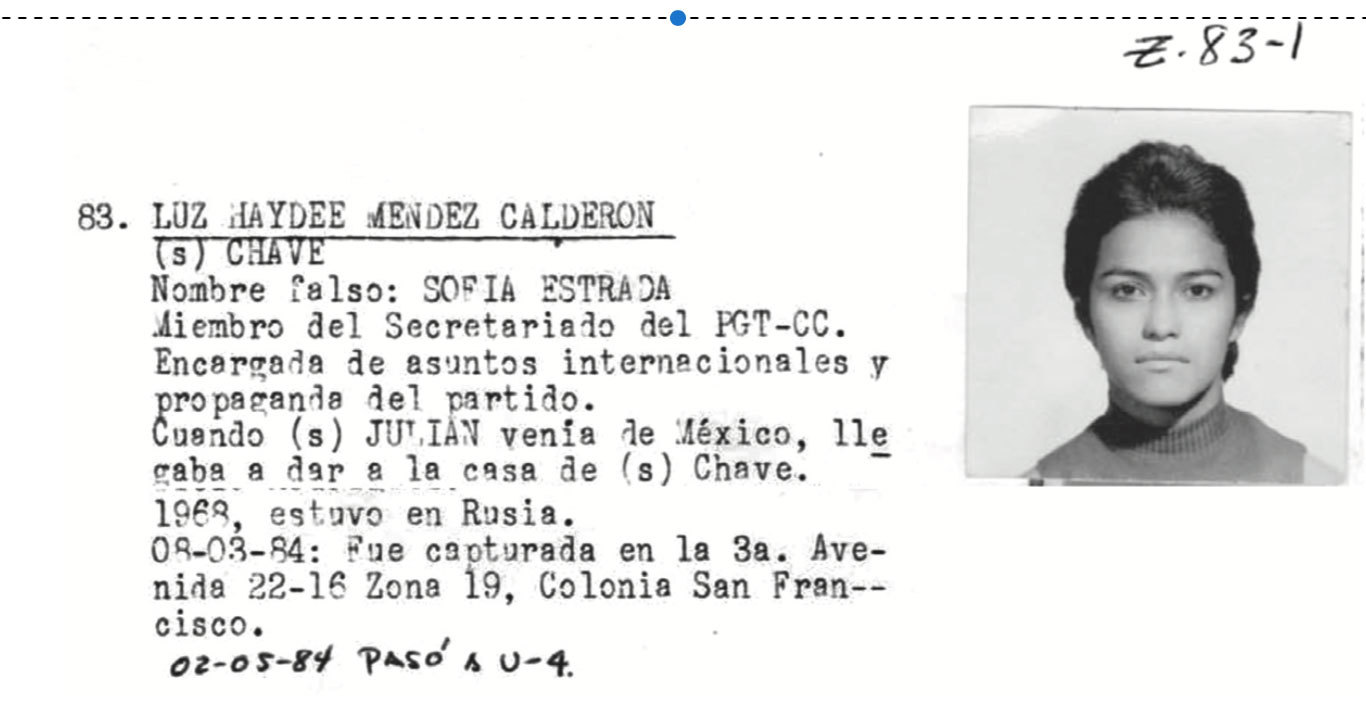

Mendez was nine years old on March 8, 1984, the day a group of men abducted her and her mother, Luz Haidee Mendez Calderon, and took them to a clandestine detention centre.

"[My mother] was charismatic when she talked to people. She was very strong, very beautiful," Mendez recalled. "I think it was like a prize for them that they found her and her daughter [to terrorize]."

That day, Mendez not only witnessed her mother being tortured but was sexually assaulted herself.

"It's not just a pervert that decided to rape a nine-year-old ― the rape was a part of the terror," Mendez said.

She believes she was drugged through food that she was given. "I felt disoriented…. The memories are just pieces of puzzles," she said. "[But] I remember the smell of blood that was new and old in that ... room." Mendez doesn't recall the sequence of events, but news clippings from that period say she was sent home a day or two after the abduction.

The Military Diary contains a final entry for Luz Haidee Mendez on May 2, 55 days after her disappearance: "Paso a U-4 [Went to U-4]." To this day, its meaning remains a mystery.

When Mendez, her brother and father fled to Canada in the mid-'80s, thousands of people from destabilized Central American countries did the same. Like many others whose lives were shattered by state violence, Mendez's family did not discuss the tragedy they left behind.

The family didn't know whether Luz Haidee Mendez might be alive in jail or in hiding. Without a body and a burial, the question hung over their new life in Canada.

As a young adult, Wendy Mendez returned to Guatemala to search for her mother, even taking part in archaeological digs that were beginning to uncover mass graves. She eventually told her story to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in San José, Costa Rica, which ruled in 2012 that Guatemala was responsible for the forced disappearances described in the Military Diary and had not sought justice for the victims and their families.

"The depression, the trauma … it's always going to be there, I just find new tools to cope with it," said Mendez. "And definitely one way to cope with that is to demand justice."

WATCH: Wendy Mendez talks about the search for her mother's remains:

The most prominent trial arising from the civil war saw former president Efraín Ríos Montt convicted in 2013 of genocide and crimes against humanity for his role in ordering a military campaign that destroyed Ixil Mayan villages and killed 1,771 inhabitants in 1982-83. But Guatemala's Constitutional Court overturned the ruling. A retrial began in 2017, with Rios Montt absent due to ill health. The trial did not continue after his death in 2018.

Mendez's greatest hope for the upcoming trial based on the Military Diary is that the defendants will break the code of silence that has surrounded other cases arising from the long and brutal war.

"I find it very healing to know that there is a judge, like a real judge, in an actual court with the people there who committed the crimes," she said. "There's a formal legal system that's actually looking into this case. After 37 years of impunity? Wow, that feels amazing."

A doctor taken in broad daylight

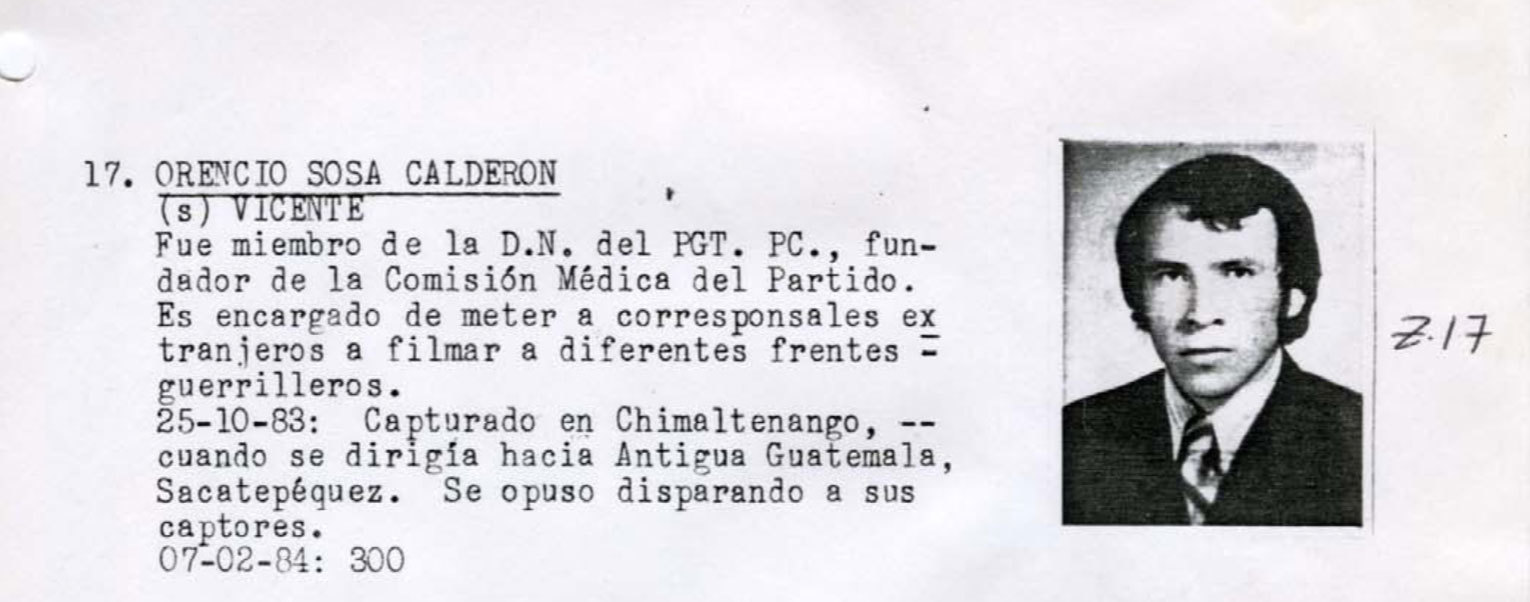

Like Mendez, Maria Consueleo Pérez remembers the day that left her family broken. At 11 a.m. on Oct. 25, 1983, panicked staff at a hospital in Chimaltenango, west of Guatemala City, called her with the news: her husband, 39-year-old Dr. Orencio Sosa Calderon, had been taken in a van after gunshots were fired.

Sosa had been wounded, they said. And he was now gone.

Later in the day, Pérez's in-laws took her to a cemetery known to be a dumping ground for bodies of the disappeared. While Pérez stayed in the car to comfort her four-year-old daughter screaming for her papa, her sister-in-law checked the grounds, but found nothing.

"There was so much fear," Pérez told CBC in Spanish.

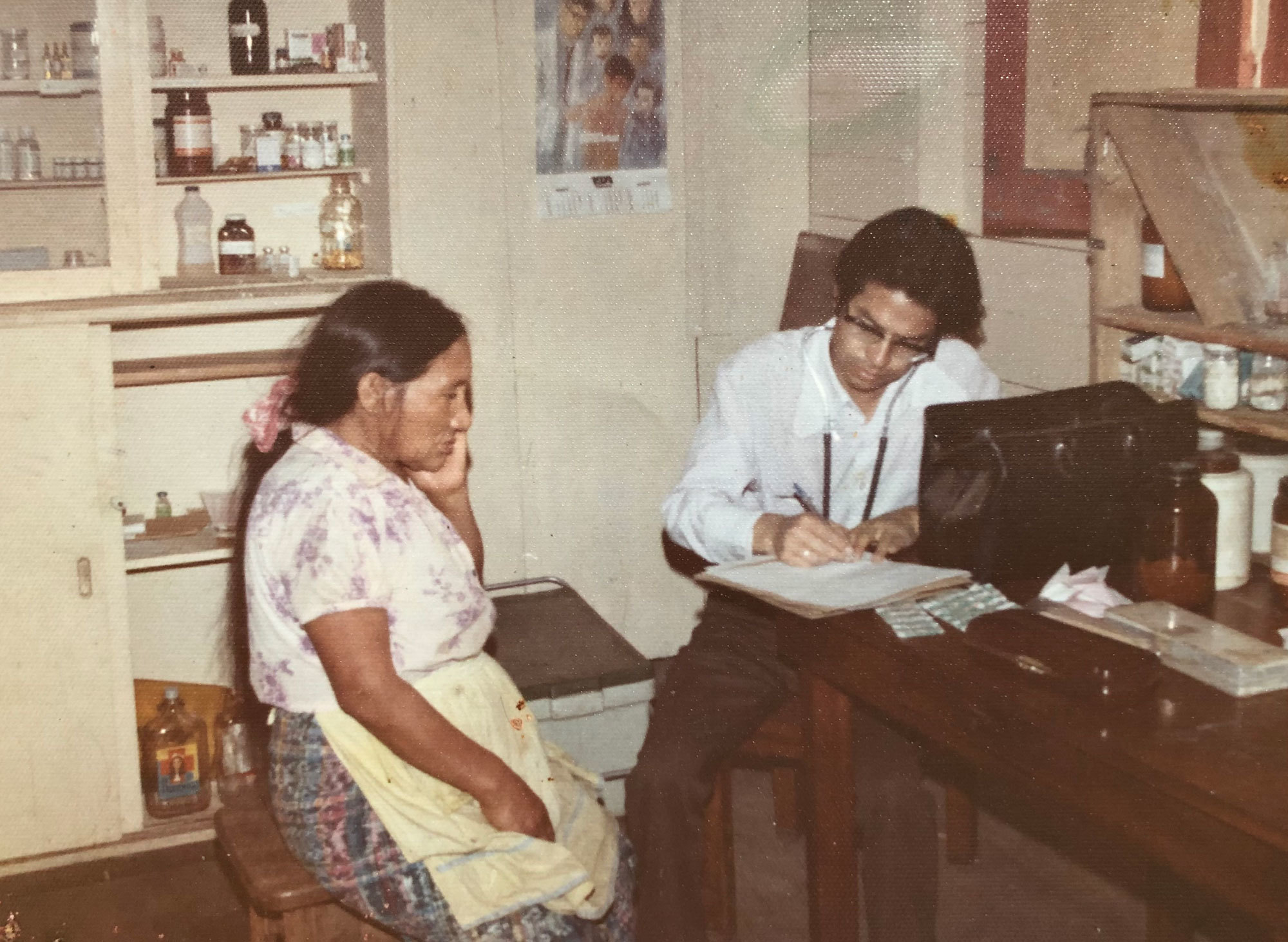

Sosa had founded a medical committee for the Guatemalan Workers Party and had also helped foreign film crews interview Mayan opponents of the government.

"He wanted to help people as much as possible. He wanted to make things better for children," said Pérez. "That there would be equal access to education, medicine, for a better future."

Pérez, then 30, was taking care of her four kids and terrified that she herself could be taken and tortured to name names. Her family made arrangements with Amnesty International to move them to Mexico as soon as possible, and the family ended up living there until 1994, when Pérez and her youngest child came to Canada to seek a better life.

Now in her late 60s, Pérez works in child care in Hull, Que., while her other grown children remain in Mexico. She says the events in Guatemala caused her family to disintegrate and created long-term psychological damage for her daughters.

While the release of the Military Diary in 1999 answered some of her questions, it also revealed agonizing details.

"We know [Sosa] fought back against his captors. So when they took him, he was already wounded," she said. "And from the Military Diary we found out that he was held for three months and 13 days, most likely being tortured — we don't know the circumstances. That knowledge is very, very painful for us."

Pérez's horror at the thought of what happened to her husband can still be heard in her voice today.

"I'd like to see the trial finish ... so everyone will know how the people in Guatemala were treated at the time."

A missing husband

In October 1983, Annabella Jiménez, then a 22-year-old private school teacher, was staying at her mother's house because her foot was in a cast.

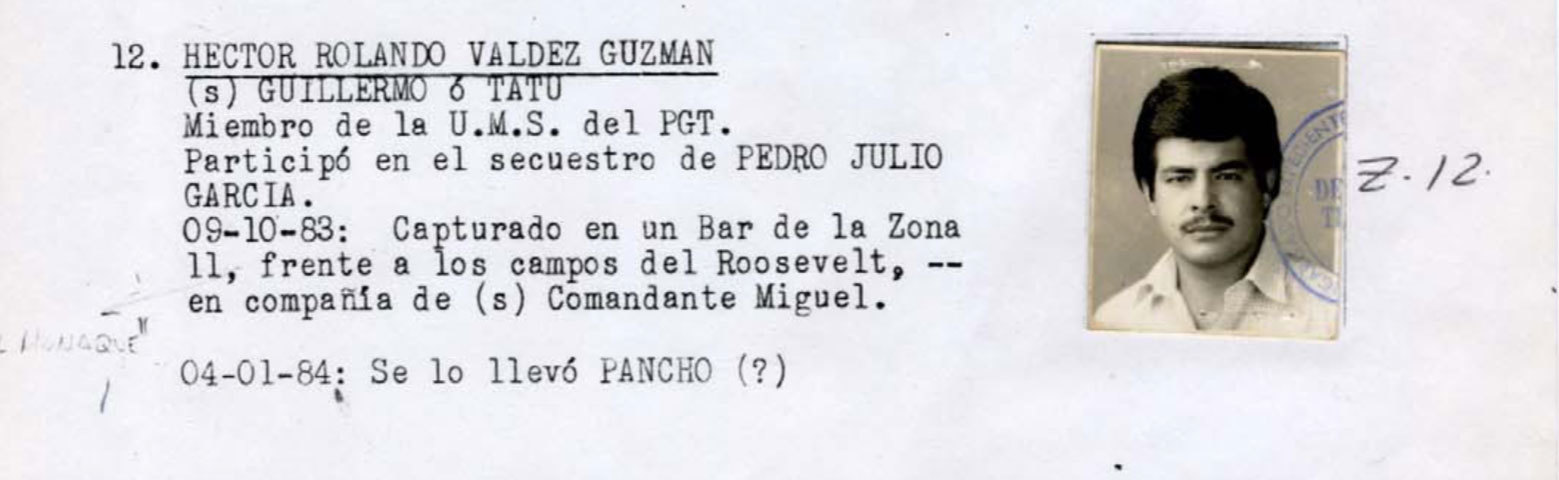

One Sunday, her husband, 25-year-old Hector Rolando Valdez Guzmán, picked her up along with their young son and dropped them off at a circus in Guatemala City.

"Rolando came and got us ... There was a show in the morning. He was supposed to come back at midday to take us to my mother-in-law's house," Jiménez said. "It was a family tradition."

But Valdez Guzmán, who was also a teacher, never came back. That night, Jiménez was stunned to see black-and-white images of their home splashed across local TV news. A breaking news report said government officials had raided a guerrilla stronghold and apprehended unnamed criminals.

"So I concluded that Rolando had been arrested," said Jiménez. "But we thought it was just an arrest, not that he was disappeared."

Why would Valdez Guzmán attract attention? Because he was an organizer for the Guatemalan Workers Party.

Jiménez stayed in hiding with family, everyone afraid of what would happen next. They soon decided it was best for her to leave the country, so she changed her son's official government documentation to remove any reference to his father's name, and sought refuge in Canada.

By the end of that year, with complete silence surrounding Valdez Guzmán's disappearance, Jiménez began to believe he was gone forever.

"He would never leave his son that way; he couldn't go two days without seeing his son. His son was his whole life," she said, barely holding back tears. "So I knew he would never come back."

In December 1983, she and her son arrived in Canada as political refugees. Jiménez worked at the Montreal-based Catholic humanitarian organization Development and Peace for 21 years. Earlier this year, she started a job at a college library.

All three women are adamant that hearing the truth about the location of their loved ones' remains would be a victory of sorts.

Mendez wants to provide a proper burial for her mother. Some of the skeletons found in mass graves at a former military centre in Cobán, about 200 kilometres north of Guatemala City, were bound or blindfolded. She wants to free the dead from their bonds.

"On so many levels, there's a need for us to say goodbye to our family members," said Mendez.

Said Pérez, "I want to bury [my husband] in a traditional ceremony and to know where he is, to remember him and bring flowers to him."

WATCH | Annabella Jiménez talks about her hopes for the trial:

Jiménez wants to be able to take her son and grandchildren to Valdez Guzmán's grave and remember his love and legacy.

"The people who hurt him, tortured him, killed him, they have had the right to a happy life, the right to a Christmas, the right to a birthday party. All that was stolen from us, and no [prison] sentence is going to pay for that."