October 13, 2021

As Shauna Pinkerton made her way down the back alley, she pointed out the spots where used needles had been lying scattered along the ground just hours earlier.

The multi-unit building next door looked battered. Its broken windows were boarded up.

A notice of vacant possession was taped to an apartment window out back. The words "f--k off, I don't care" scrawled just above it.

"This is a known drug house," Pinkerton said. "It's a flop house. There's one person that has an apartment, but 15 that are flopping there."

Pinkerton said it reminds her of Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, where she lived for years.

But this isn't Vancouver. Nor is it Toronto or Edmonton.

It's Dryden. Ontario's smallest city.

The thing is, it's not just Dryden. It could be many small towns and cities right across the country.

If they don't get the resources they need to address cascading mental health, addiction and housing crises, some communities could soon be overwhelmed, experts warn.

Pinkerton is worried that's already the case here.

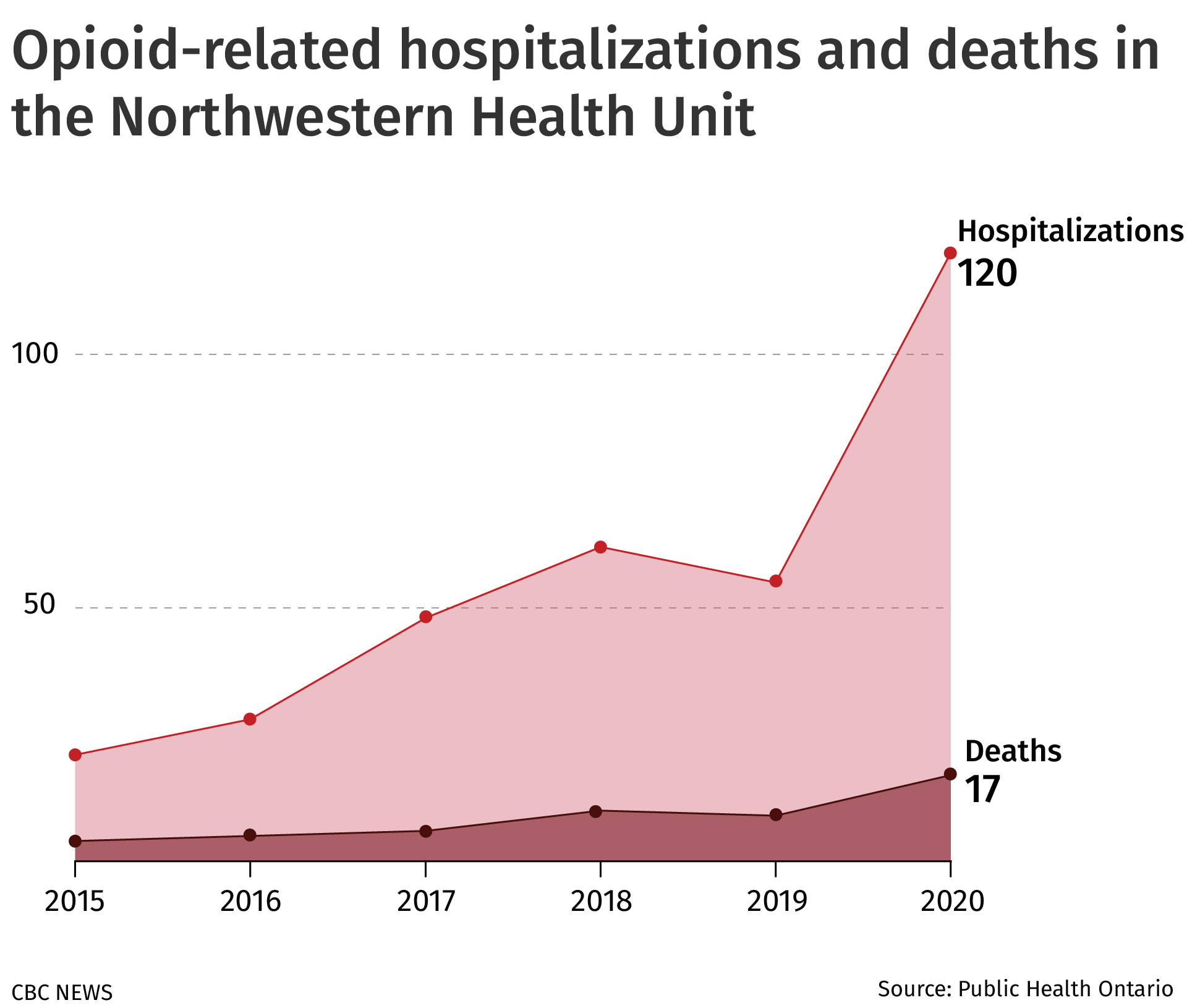

Seventeen people died in 2020 from an opioid overdose in the area covered by the Northwestern Health Unit, which includes 19 small municipalities, including Dryden, and 39 First Nations, spread across one-fifth of Ontario's land mass.

"We're in a very dire situation here," Pinkerton said. "I don't know how much more death and despair we need to go through before we can get some help here."

WATCH|Shauna Pinkerton tells her own story of addiction and recovery:

Shauna Pinkerton, 44, was born and raised in Dryden, Ont. She wants to bring attention to the mental health, addiction and housing issues affecting the city.

The flop house

Mikey Verbonac was carrying a full garbage bag through the alley when Pinkerton called him over.

Turns out, he was the one who cleaned up the needles earlier in the day.

Verbonac pays $780 a month to live in a narrow, one-bedroom apartment in the building next door, so it's important to him to keep the area clean.

When Pinkerton asked how he's doing, Verbonac pointed to a large hernia protruding from his abdomen.

"If it breaks, I'm dead," he said doctors have told him.

"I'm a drug addict. I like to use drugs, I like to drink, but I also like to wake up. That's the most important part of my day."

Pinkerton called her friend "our star survivor," as they recounted the 32 times Verbonac says he's been stabbed, including twice in the head, which left him in a coma for several days.

"I got stabbed, I died and came back," he said. "There's got to be a reason for me coming back, so now I just try and help everybody. I help out more people than I help my own self."

He said he walks around at night helping people in need. He hands out new needles and picks up discarded ones on the ground.

Inside Verbonac's apartment, the ceiling fan hummed while music from the local radio station played in the kitchen.

He said he often has to make space on the floor for people to sleep.

"When you gotta get up to use the washroom, you gotta crawl over bodies because I got nine, 10 people here sometimes at night," he said.

There is no homeless shelter in Dryden.

At last count in 2018, there were 67 homeless people in the city of about 8,000.

Verbonac said it's hard to keep opening his door. He said he's had a lot of things stolen: his bank card, keys, dishes, even some of his dirty clothes.

"They're all homeless. They have no place to go, and I open my door to them."

As Pinkerton went to say goodbye, she turned to her friend.

"Is there anything that you need?"

"No, I'm good," he said. "Love you."

"Love you, too."

Later in the day, Pinkerton went back anyway.

Strained resources

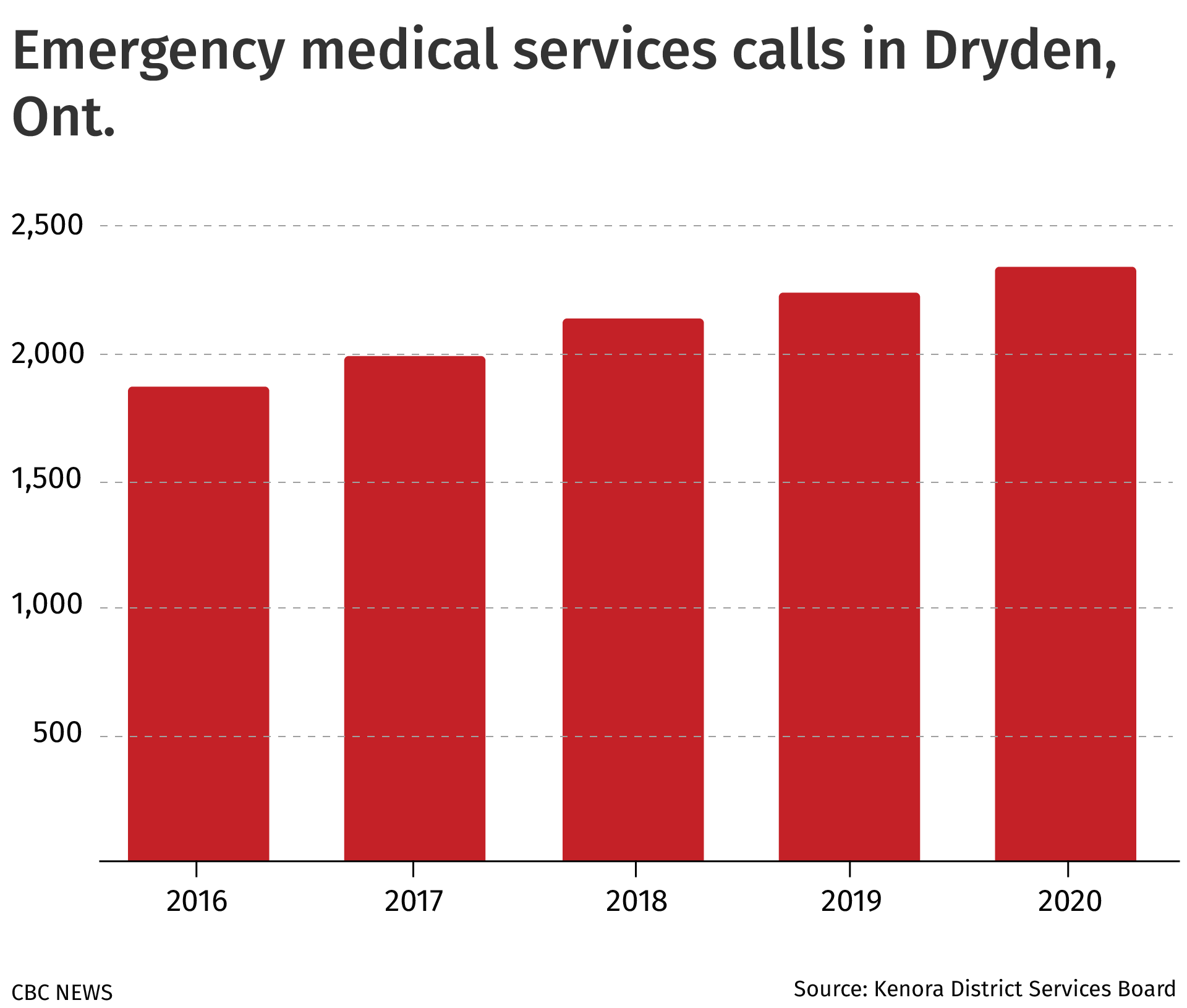

In the past five years, there's been a 25 per cent increase in calls for EMS in Dryden.

Since 2019, there has been a 60 per cent increase in mental health and addiction-related calls.

Dryden had one-third of all overdoses reported in the Kenora district last year despite having one-tenth of the region's population.

Opioid-related emergency department visits have also dramatically increased since 2015 in the Northwestern Health Unit area.

Meanwhile, other dangerously addictive substances, such as crystal meth, continue to flow into Dryden.

It's all putting a strain on the resources that are available, said Doug Palson, the city's police chief.

Not only does the city lack a shelter, it doesn't have a permanent warming or a cooling space. There is also no safe consumption site or detox centre.

People are in the streets at all hours, whether it be 30 C in the summer or -30 C in the winter, Palson said.

Sometimes, people are too intoxicated to take care of themselves and have nowhere to go.

"The majority of these issues are not crime issues," he said. "They're not even something that police should be directly involved in, unless there's a safety issue."

But police are the only social services response available 24/7, so a lot falls to them, he said.

"We respond as best we can, but ... it's a bit frustrating."

It's also taking a toll on front-line health workers.

Marcel Penner is the director of mental health and addiction services with the Dryden Regional Health Centre.

He said the number of referrals to mental health programming has remained consistent over the years, but there are more people coming to the hospital in crisis.

"The pressure is very high," he said.

It's heightened, he said, because the hospital's mobile crisis team is understaffed and unable to run on a 24/7 basis, like it's funded to do.

"It's a matter of recruitment," he said.

This story in Dryden is one that Sarah Kennell says she hears all the time.

She's the national director of public policy with the Canadian Mental Health Association, a national organization that provides advocacy, programs and resources to support mental health.

It's a story that's being experienced in small towns and cities right across the country, she said.

Many front-line service providers are burnt out, anxious and depressed. Many are now leaving the profession, Kennell said.

Meanwhile, wait lists for supportive housing and treatment centres grow. Opioid and other drug overdoses and deaths continue to climb across the country.

And despite the attention briefly given to mental health, addiction and homelessness during this past federal election, little regard was paid to the particular problems facing rural and remote communities, Kennell said.

But she said the solutions are well known.

They include investing in supportive, affordable housing; opening treatment centres in smaller communities; training specialized health-care workers and sending them to rural areas; expanding Indigenous-led mental health programming; and ensuring access to a safe supply of drugs and supervised injection sites.

"There's no doubt, we know what the solutions are," Kennell said. "It does come down to political will and resources."

Dryden's mayor says the political will is there, but the resources aren't.

"We see media releases by the governments saying we're going to spend X number of billion dollars over the next so many years on increasing mental health support," said Mayor Greg Wilson.

"I don't feel like a lot of that money has come through the system effectively."

In an emailed statement, the Ontario government said it has invested $525 million in new funding since 2019, and has promised to invest $3.8 billion in mental health and addiction services and supports over 10 years.

The statement also said the government has tasked Ontario's Mental Health and Addictions Centre of Excellence, a government agency created in 2020, with implementing its plan to modernize the province's mental health and addictions system, including the development of performance metrics.

Shauna's story

Everyone living and working in Dryden who spoke with CBC News about the mental health, addiction and homelessness situation in the city said a version of the same thing: The problems are growing and becoming more complex.

So, what will happen if Dryden doesn't get the investments that many say it needs to help people?

Some struggle to answer the question, but Shauna Pinkerton doesn't bat an eye when asked.

"People will die."

Pinkerton, 44, knows because she's been living with addiction for much of her life.

"By 12, I had smoked crack. By 15, I was completely dependent on THC and alcohol," she said.

A few years later, she moved to Vancouver with her boyfriend at the time, and within a year, she was living in the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood.

"I did get involved in prostitution and hustling when I was on the street, so I basically went into pure survival mode."

After a year without a single call home, Pinkerton's mom flew to Vancouver, tracked her down and brought her back to Dryden. That was in the mid-90s.

Back home, she had her first son and continued to struggle with addiction. Then, her son was taken from her.

"After he got taken away was the big wake up," Pinkerton said. "Then it was like, what do I need to do to get back on track to get my son back living with me?"

It took her about a year to get her son back.

She did a little bit of advocacy over the years, writing letters in support of bringing a needle exchange program to Dryden, but mostly tried to help in the background, she said.

That all changed this past winter.

Three young people died by suicide. Someone else died after a serious assault. Another overdosed. All people Pinkerton knew personally, all in the span of a couple months.

It was too much.

As COVID-19 forced the few remaining resources in town to shut their doors to the public, Pinkerton couldn't just sit quietly anymore.

She started a Facebook page to bring attention to the mental health and addiction crisis ravaging the city. The group has more than 1,200 members.

She started distributing clean needles to houses where people commonly gathered to use drugs. And buying groceries and essential items for those in need. Handing out water. Giving rides. Lending her phone for remote court hearings. Naloxone kits went out as quickly as she could get them, she said.

She gave whatever she could.

Pinkerton said she faces a lot of criticism. Some people call her reckless. They say she's enabling drug users.

But at 44, having been through everything she has, Pinkerton said her harm reduction approach is not up for debate.

With such limited resources available in the community, if she doesn’t do this work, Pinkerton is worried no one else will.

"Every day is a struggle," she said. "People say, 'Why would you put yourself in danger like that? You've got kids to think about.'"

Pinkerton said she's been talking to her counsellor about the toll her harm reduction work has been taking, but she has no plans on stopping.

She said people never gave up on her, so she can't give up on others.

"I'm smart enough to know that I'm not going to save the whole world, and I'm not going to save everyone," she said.

"But if I can save one person or help one person, then I'll do my job."

The solutions

As the director of mental health and addictions at the Dryden Regional Health Centre, Marcel Penner is tasked with providing the addiction management resources that people need.

But he says his ability to do so is severely hampered.

There is no detox centre where people's withdrawal symptoms could be managed. There is also no residential treatment centre for people who are ready to start treatment today.

"Those services don't exist. They're not very easily accessible in our area."

Those sentiments are echoed by other mental health program directors in the region, Penner said.

Instead, people in northwestern Ontario typically withdraw on their own, or they go to the emergency department.

"That's not really the best-case scenario," Penner said.

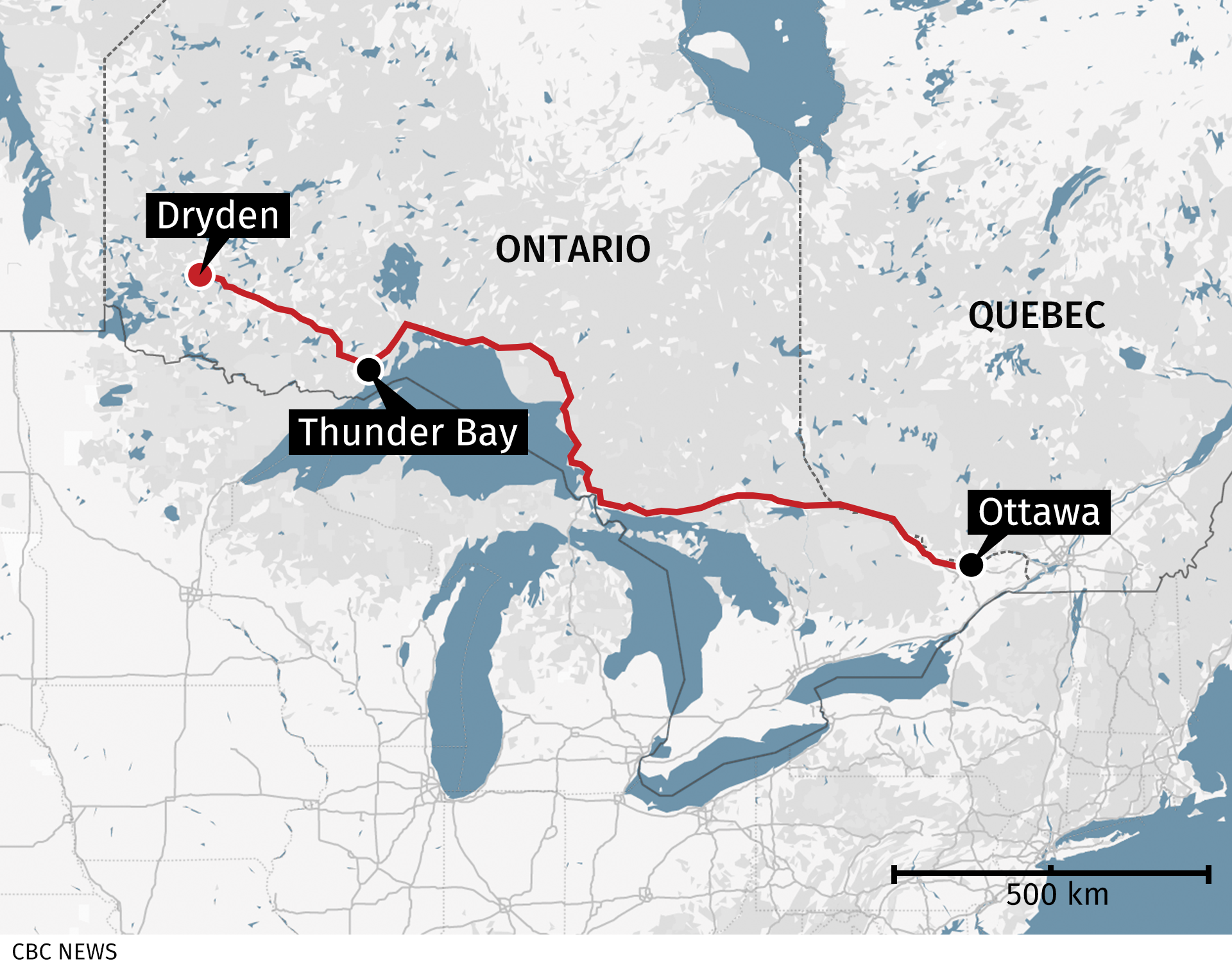

If someone is ready for treatment, they would then need to get a referral to a treatment centre hundreds of kilometres away in Winnipeg or Thunder Bay, or sometimes even farther away.

That separates people from the network of personal support they may have built up in their community. Not to mention the long wait lists and transportation obstacles they often face.

"If you have to wait months to get into a treatment program, you can imagine it's just very difficult for many people to get to that point," Penner said.

One solution, he said, would be to build a treatment program right here in Dryden.

"Maybe a dream of mine, but it could make a difference," he said. "These things can happen, but they can take a great deal of time."

That’s something Henry Wall is trying to accomplish.

He's the chief administrative officer of the Kenora District Services Board. Whenever a conversation about mental health and addiction starts, Wall's name is inevitably mentioned.

Wall said there is a desperate need to "de-industrialize treatment" and bring it back into the community.

The idea that people need to leave their community and travel hundreds of kilometres to be treated doesn't work, he said.

"It hasn't worked in the last generation, and it's certainly not going to work moving forward."

He recounted how there was recently a young woman who was ready for treatment, and workers with the services board helped her get a bed at a residential treatment centre in Ottawa.

That's 1,820 kilometres southeast from Dryden.

All the arrangements were made for her trip to Ottawa. But when she arrived, the bed wasn't ready for her. She was told she'd have to stay in an emergency shelter until the bed became available.

"We brought her back because we knew that we'd just set her up to fail," he said.

It's a story that is bound to repeat itself, he said, if more isn't done now.

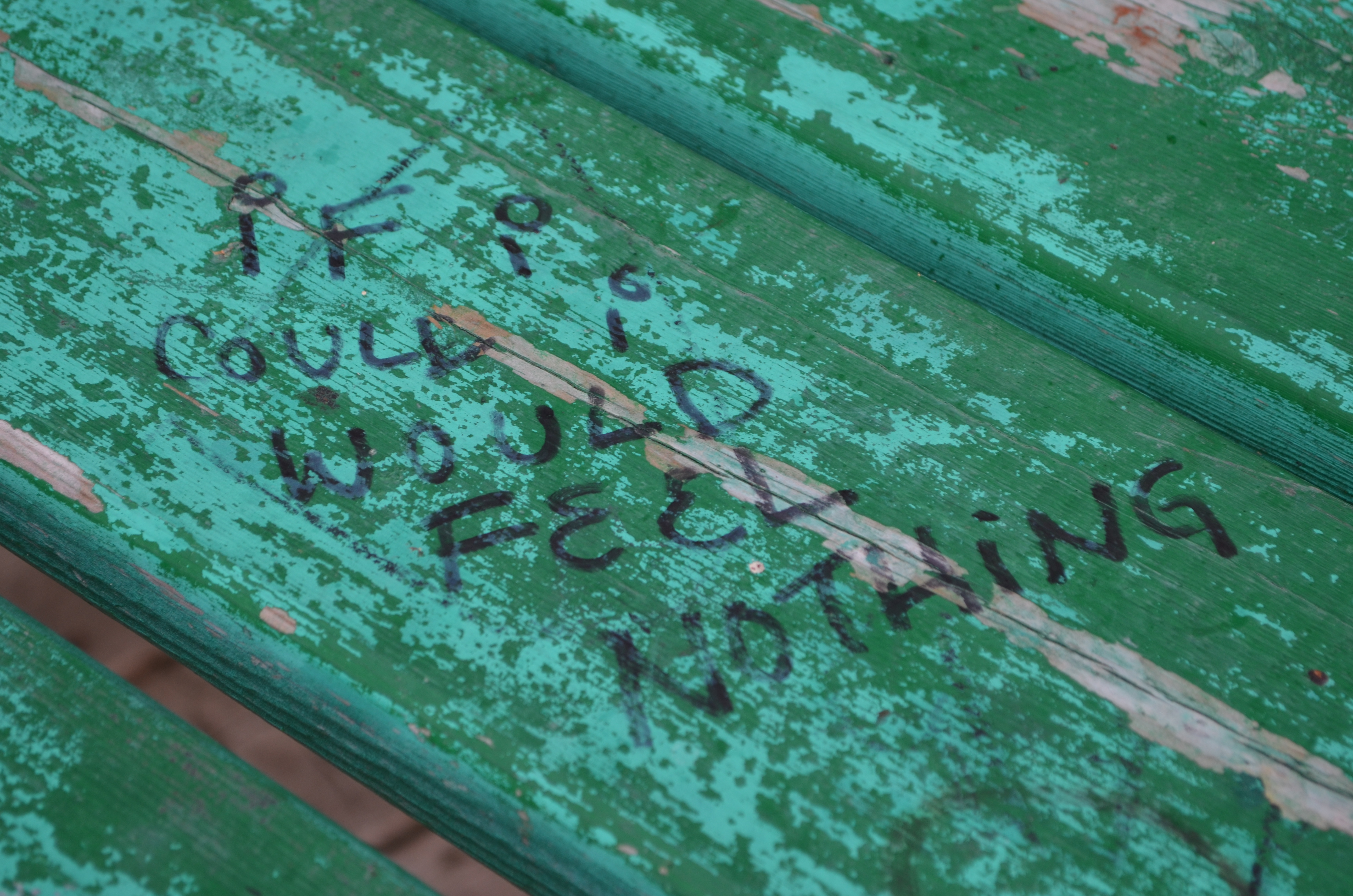

A note scrawled on a picnic table in a downtown park in Dryden reads like a cry for help to Shauna Pinkerton. (Logan Turner/CBC)

'If I could, I would feel nothing'

As the sun set over the city of Dryden, Shauna Pinkerton walked through Cooper Park on the banks of the Wabigoon River.

The park connects to the downtown core and is a gathering place for many community events.

Pinkerton passed a memorial for a friend who died the previous winter and pointed to the words written on a green picnic table: "If I could, I would feel nothing."

She said this is what people in Dryden are up against. The pain of past traumas. The hurt of not feeling seen. The desire to hide it all with substance use. The apathy.

Pinkerton isn't sure if she'll stay in Dryden forever.

But before she goes, she said, she wants to see change in her hometown.

"It looks like kindness and compassion. That empathetic voice at the end of the day."

It looks like people feeling seen, she said, and having their stories heard.