December 29, 2020

Latresha Jackson initially recoiled at the idea of moving to a community with a notoriously racist past.

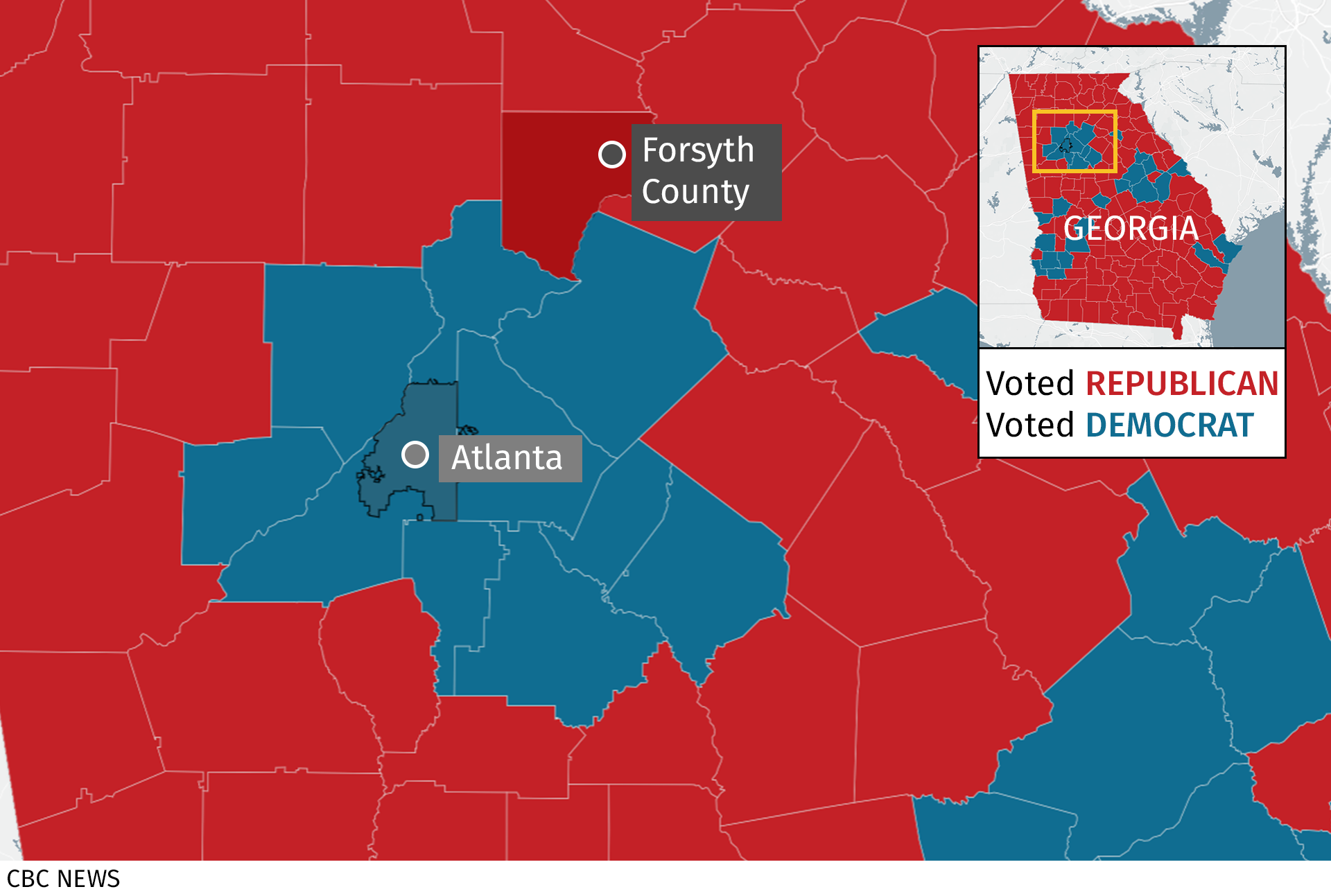

It was infamous as a whites-only area just north of Atlanta. About a century ago, Forsyth County's Black residents had been chased away by their white neighbours, who established a zone of American apartheid so shockingly durable it made national headlines into the late 1980s.

An African American woman originally from New Jersey, Jackson chafed when her realtor kept sending her listings for homes in Forsyth County.

"I was like, 'Dude, we're not going there.' I was like, 'Stop it,'" Jackson said. "Because of the history."

But the schools won her over. An MBA and accountant who moved to Georgia for an executive job, Jackson wanted the best possible education for her children, so in 2013, she settled in Forsyth. As have tens of thousands of other people from all over the United States and around the world, drawn by the area's stellar schools, large houses and proximity to the economic juggernaut of Atlanta.

That influx has political implications. Jackson, for example, now volunteers locally with the Democratic Party.

The dramatic changes in this one county provide a vivid snapshot of a broader story, one that’s now drawing national and international interest.

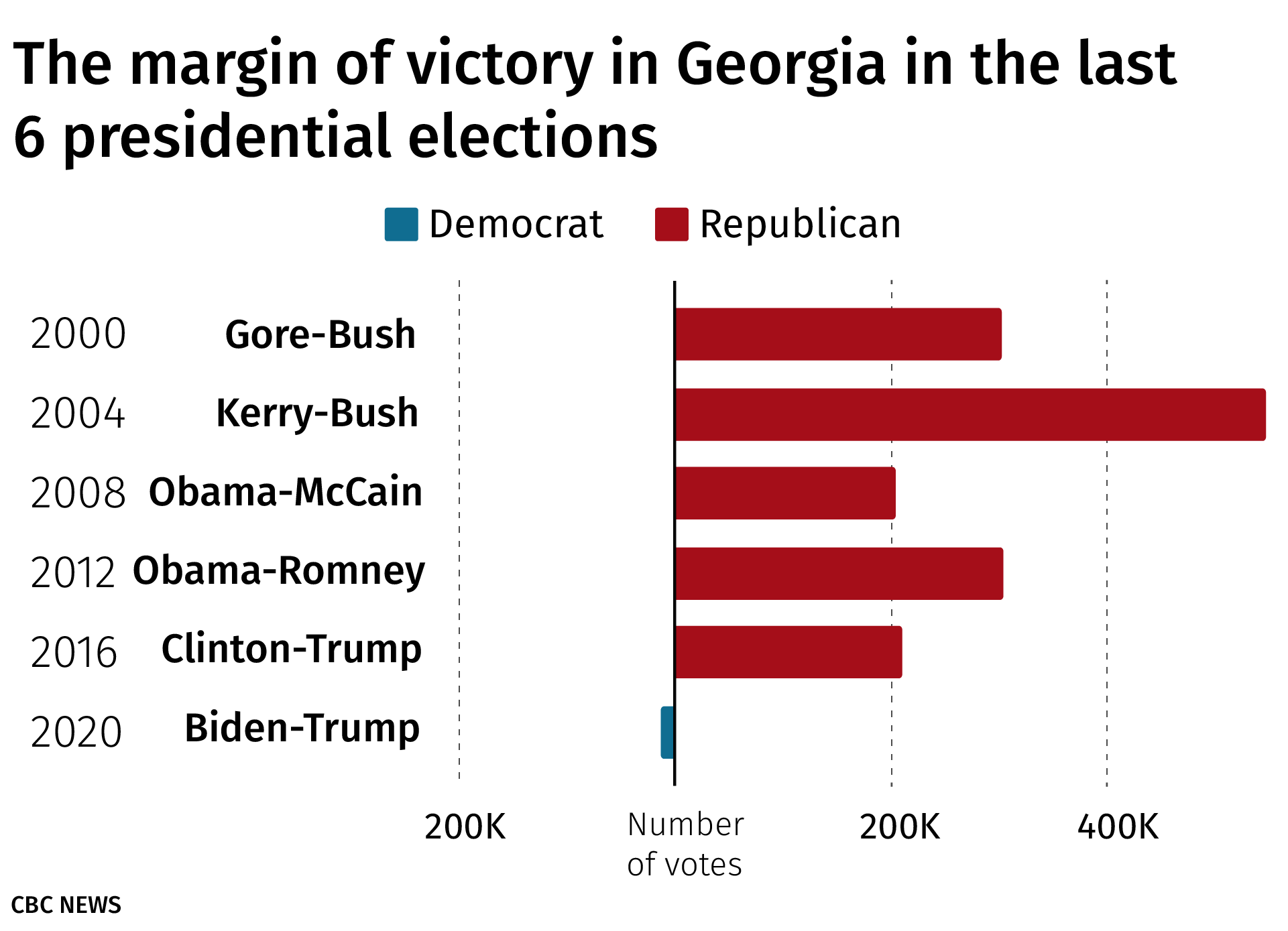

It's the story of how Georgia has catapulted to the epicentre of American politics. On the heels of a surprise victory here for Democrat Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election, the state will now play kingmaker in deciding which party controls the U.S. Senate, with two hard-fought races on Jan. 5 — one pitting David Perdue (Republican) against Jon Ossoff (Democrat) and the other between Kelly Loeffler (Republican) and Rev. Raphael Warnock (Democrat).

Hundreds of millions in political donations and thousands of political party operatives are pouring into the state for races that hold considerable consequences for Biden's presidency.

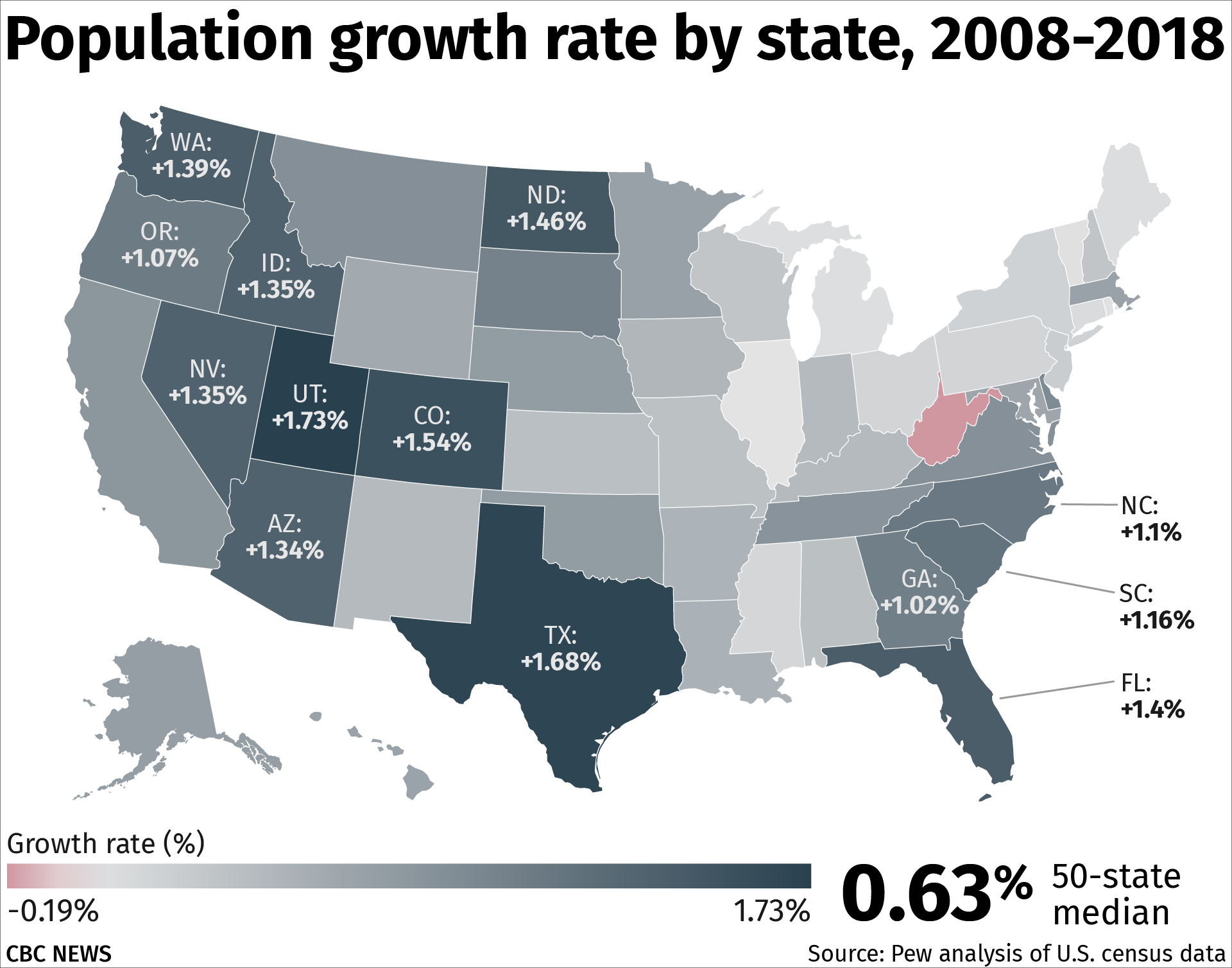

Atlanta's booming economy has radiated growth into an expanding ring of suburbs, including Forsyth, which in just a generation has metamorphosed into a thriving area hosting plants owned by German, Japanese and Israeli companies.

That explosive development has seen the county population double, then double again, then grow some more — multiplying six times since 1990, with old farms being gobbled up by new housing subdivisions, shopping centres and luxury-car dealerships. It's now part of a broader Atlanta region that houses the U.S. or global headquarters of Delta Air Lines, UPS, Coca-Cola, Porsche, Mercedes and Home Depot.

Unemployment is nearly non-existent here (2.8 per cent), even during the pandemic, while education levels are sky-high — the 53 per cent postsecondary graduation rate is nearly double the state average.

For geographic context, Forsyth County is just outside the inner suburbs of Atlanta, those places that constantly popped up on cable-news screens during the multi-day drama that was the 2020 U.S. presidential vote: the counties of Fulton, Gwinnett, Cobb, DeKalb.

Forsyth is just beyond the suburban ring, which voted Democrat. Republicans still dominate here, but the numbers have been shifting with abnormal speed. Democrats were being outvoted here by nearly five to one; it's now two to one, with Democratic vote totals tripling since 2012 and growing by almost 24,000.

It resembles the trendline playing out in some southern and western U.S. states experiencing an influx of migration.

What makes Forsyth County, Ga., unique, however, is its not-so-distant racist past. This was a place that even legendary civil rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis would not venture to, according to one local politician. It's a place where Oprah Winfrey taped an episode of her talk show in the late '80s and fled town before sunset, because she felt unsafe spending the night.

II. What happened in Forsyth

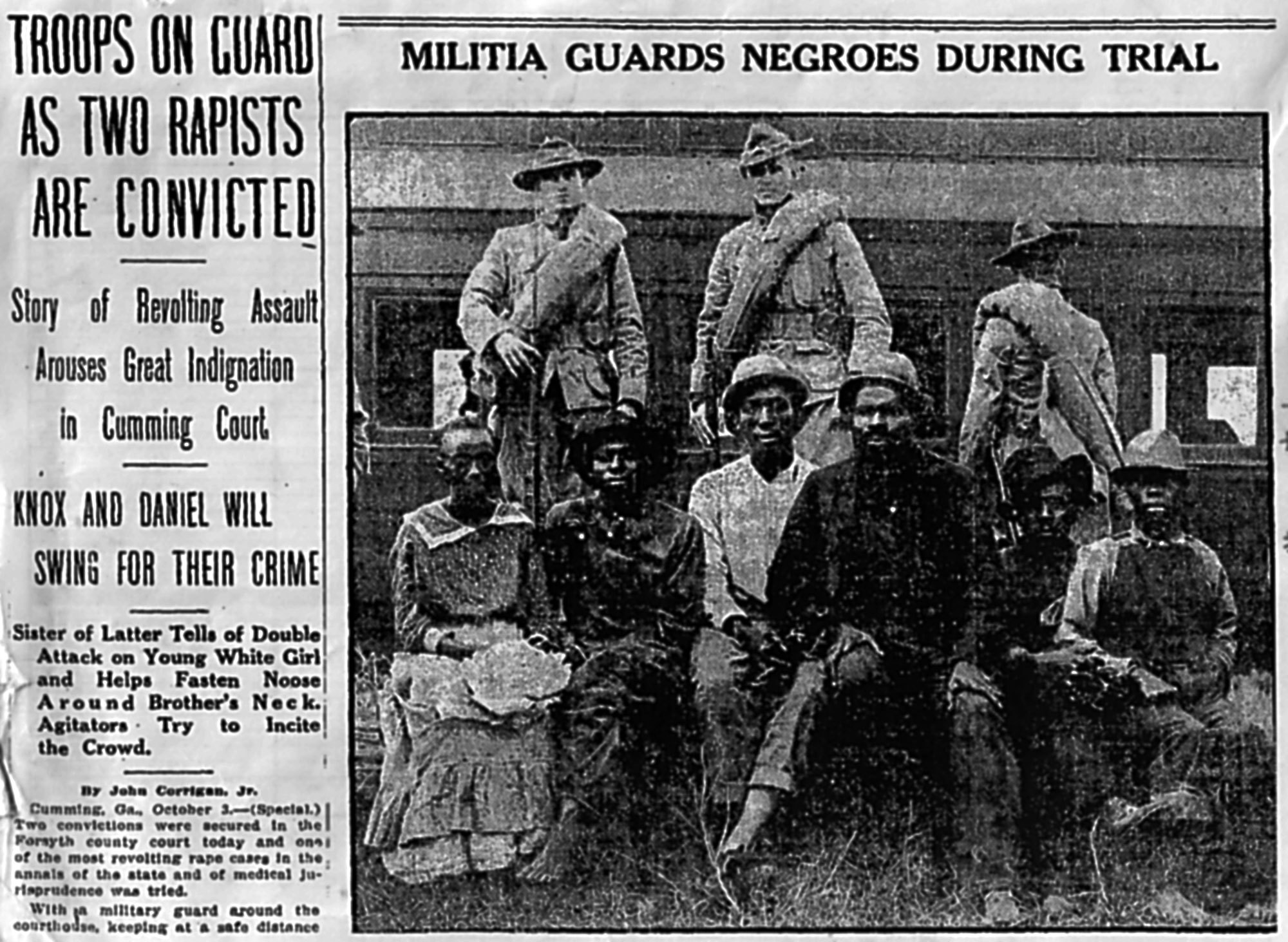

The events of 1912 made national news, albeit on a scale that barely conveyed the crimes perpetrated north of Atlanta.

On Page 11 of its Dec. 26 edition that year, The New York Times ran the headline: "Georgia in Terror of Night Riders." The report about escalating tension in the area cast whites as the victims, emphasizing how two white women had been attacked and that white landowners were being threatened for employing Black labour.

A fuller account of what happened came in Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America, a deeply researched book published in 2017 by Patrick Phillips, a former resident of the area. The book begins a few decades before the tragic events and suggests the stage was set by an earlier mass expulsion.

Area residents had grown up hearing about how in the 1830s, in this same county, the Cherokee were brutally uprooted from their Indigenous homeland and forced west. Then, a new generation committed the same crime — against new victims.

Phillips says this "racial cleansing" began when a white farmer arrived home around midnight in the fall of 1912. He reportedly said he heard a scream, and entered a room to find his wife in bed with an African American man. He said his wife declared she'd been attacked.

In a separate incident days later, another young white woman, Mae Crow, was found in the woods after being beaten. She soon died from her injuries.

In response, a mob of angry whites lynched a Black man and mutilated his body in the town centre of Cumming, the county’s largest municipality.

Following a trial for suspects in the Crow attack — conducted under a cloud of legal irregularities — there were two public executions in that same square, as thousands of white residents cheered while a pair of Black suspects were hanged. Milling about among the cheering mob was the county sheriff, who later became a charter member of the Ku Klux Klan.

In a wave of mob violence, Black homes and churches were burned, rocks were tossed through people's windows, bullets were fired into front doors and residents were ordered to leave by the next sundown.

Within months, virtually all of the 1,098 African Americans listed on census records had been chased from the county. Former neighbours, the area's white residents, took their houses, possessions and livestock.

According to Phillips's book, that racial vigilantism was in force well into the modern era. In 1980, a local man shot a Black visitor in the head, nearly killing him, upon spotting him at a company picnic in Forsyth. Phillips also writes that in 1986, five Mexican construction workers were beaten by a group of residents and told they'd be killed unless they left the county.

In 1987, civil rights protesters came to the county for marches, and were confronted by white-power rallies, Confederate flags and signs that said things like "Keep Forsyth White."

These incidents brought a gusher of national media attention. Oprah Winfrey came here to tape a 1987 episode of her talk show. Still viewable online, it features a jaw-dropping torrent of racial epithets and slurs from audience members.

A Washington Post headline that year called Forsyth "[The] County That Progress Forgot."

But even in the midst of that, signs of progress were emerging. A number of the guests on Winfrey's show said they knew things needed to change. And change they did — the older population died off; younger residents connected with the outside world; and thousands moved in.

III. A different place today

In 1990, the census listed 14 Black people as living in Forsyth. Now, there are nearly 10,000 Black residents, making up 4.4 percent of a population with large minority communities.

Today, nearly one-quarter of the county is a visible minority, as people flock here from elsewhere in the U.S., South Asia and Latin America. That trendline will only accelerate, as area schools are even more diverse than the general population.

Retired teacher Anna Purcella-Doll witnessed the change first-hand. A native of Albuquerque, N.M., she and her husband moved to Georgia for his job in the insurance industry and settled in Forsyth in 1997.

A woman of Mexican descent, Purcella-Doll recounts mentioning to her husband something she'd noticed upon their arrival. "It's really strange," she recalled saying. "I'm the only person who looks like me here."

She later asked a girlfriend about the absence of minorities on the outskirts of Atlanta's suburbs. The friend replied: "Anna, you [don't] know about Forsyth County?"

Another friend, a Black man, once expressed disbelief that she lived there. Working as a trucker, he avoided assignments to Forsyth.

Purcella-Doll recalls the first time she saw a Black person working in the Cumming area: it was the year 2000, at a Verizon store. Nowadays, she estimates nearly one-third of the people in her housing subdivision are people of colour.

Like many newcomers, Purcella-Doll brought her politics to Georgia. A lifelong liberal, she'd stamped envelopes for Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern in 1972 and worked for a Democratic senator on Capitol Hill during the 1974 Watergate hearings.

Yet upon arriving in Forsyth, she occasionally organized events for Republican candidates she liked who were running in down-ballot races. The reason was simple: there were no Democrats competing locally.

WATCH | Democrats hopeful of winning crucial Senate seats in Georgia:

Connecticut native Eric Cohen tells a similar story. The e-commerce entrepreneur arrived in 2008 after living in different parts of the country. He came to Georgia because his wife's family is here, and they chose Forsyth for the good schools and low taxes.

He experienced culture shock when he brought his boys to school.

"Basically everybody's blond and blue-eyed. You've got these kids with a Jewish dad going into this public school and it was quite jarring," Cohen said, sitting for an interview on his front porch. "The kids were basically the only dark-haired children in the school.… I don't want to say [it was] a time warp — but things were different."

Cohen arrived just weeks before the 2008 presidential election. He recalled driving around the county and seeing only four Barack Obama campaign signs.

He said being a Democrat in this area, especially back then, created a chill in conversations. He said people would unironically tell him things like, "You're a Yankee."

When it came to politics, "you'd kind of speak in code language," Cohen said. "Democrats [here] were essentially closeted."

After Donald Trump's election win in 2016, Cohen got involved again in partisan organizing. He now volunteers locally with the Democratic Party, which he said distributed between 700 and 800 signs in the area for Joe Biden this year.

Until recently, Democratic Party meetings were held in a local funeral home. The establishment's owner, a Republican who just got elected to the state legislature, offered free space for meetings as a civic favour.

"It was a running joke that Democrats met at a funeral home, because the party was dead," said Melissa Clink, the Democrats' chair in the county. "Now [Republicans are] paying attention to us because we're putting numbers on the board."

Indeed, Biden actually won a precinct on the southern edge of the county, closest to Atlanta. A Democrat also won a seat in the U.S. Congress that includes that southern tip of Forsyth; in fact, it's the only new seat in the House of Representatives that the Democrats picked up anywhere in the country this year.

The county is split into two political worlds. That southern zone, closer to Atlanta, is increasingly Democratic; the more rural northern part, farther from Atlanta, is ruby-red — in fact, in one remote northern precinct, Biden got just 18 per cent of the vote.

Clink alluded to that divide when, during an interview in the middle of the county, a truck zoomed by with Confederate flags fluttering from it.

"Now you're getting north," she said.

Clink grew up in diverse places like Charleston, S.C., and Orlando, Fla., and moved here 11 years ago to be near Lake Lanier and the area's bountiful nature.

"When I got here, I was culture-shocked," she said. She recalled sharing her political views once with a work colleague, and the woman said, "I can't believe it. I'm gonna tell my husband I met a Democrat."

Clink's not just any Democrat — she was a delegate at the 2016 Democratic convention for Bernie Sanders, the self-described socialist senator.

IV. Culture clash with conservatism

As one might imagine, an influx of liberals and even supporters of socialists has created something of an ideological culture clash with longtime residents of formerly conservative Georgia.

Many argue that capitalism and a conservative approach to government is what made this place prosperous.

Carter Patterson, a local entrepreneur and chair of Forsyth's chamber of commerce, said the new diversity is a triumph to celebrate. But he said old and new residents disagree when it comes to political ideology.

"That conversation has taken place a lot," said Patterson, a Republican who moved into the county in the 1990s. "People move in, and they don't realize that it's really been a Republican-led evolution of our county … of conservative principles that have built the best schools and some of the highest per-capita income in the state."

Georgia has one of the oldest anti-union laws in the country and has lower-than-average corporate taxes.

Patterson is local co-chair of the Senate campaign for David Perdue, and says the area's low-tax, low-regulation attitude is worth preserving. For example, he said when the county needs more money for projects — like a new school or roads — it tries raising funds by issuing a temporary bond instead of raising taxes indefinitely.

"It keeps our politicians fiscally sound," he said.

Erick Erickson, a prominent conservative talk-show host based in Atlanta, said newcomers to the region tend to promote ideas that are popular where they're originally from. He cited examples such as expanding public rail and a preference for funding public schools over charter schools.

He said those approaches don't necessarily work for this place, given the realities of its transportation network or Atlanta's poor public schools.

Latresha Jackson said these policy disagreements sometimes stir up undercurrents of racial tension. For example, she said any talk of extending the rail system or of building affordable housing winds up prompting comments about keeping certain people out of the area.

"I'm not going to say it's all roses and butterflies up here. We definitely still have issues."

Lest the point be lost on anyone, she said, the undertone is that these certain people are Black.

"I'm not going to say it's all roses and butterflies up here," Jackson said. "We definitely still have issues."

Yet after seven years of living here, her bottom-line takeaway? This has been a good place to live.

Jackson told a story dating back to her arrival in 2013. She went to town hall to register her address for the new home she had built, and recalls something a municipal employee told her.

"I remember one woman saying, 'We're so happy you're here. This place is changing. Welcome,'" Jackson said. "People were nice. People waved. People were friendly. We thought they were kind of going to be giving us nasty stares."

It's hard to envision a more striking example of change in this community than Daniel Blackman standing where he was standing earlier this month, discussing his political plans. Blackman is running for a state-level position to lead Georgia's utilities regulator in a race happening on Jan. 5, the same day as the federal Senate elections.

The fact that he now lives in Cumming would have been hard to imagine within his own lifetime. That he's seeking statewide office; and talking about it in a media interview in the town square; and that right beside the square there's a Latino grocery store and a taqueria — all of it would have been inconceivable a generation ago.

"There was a time I couldn't stand right here. … Within my lifetime, thirty years ago," said Blackman, the son of Caribbean immigrants. "There was a culture and a sense that this area was off-limits."

This year, in the same town centre that witnessed a lynching and public hangings in 1912, hundreds of people participated in a Black Lives Matter march.

As Blackman stood there for an interview with CBC News, a police officer walked up and asked what was going on.

The officer was told Blackman was a local resident running for statewide office. The policeman sounded surprised and asked, double-checking: He's from here, running for statewide office?

Yes, he was told.

"Cool," said the officer, who gave a thumbs-up and walked away.