In the rolling hills near Bentley, Shane Juuti walks among a herd of yaks.

Wearing a cowboy hat and leather vest, he talks to the animals, then stops and pets a bull named Brutus, who was raised by Juuti’s children.

The yaks migrate from field to forest, lazily mowing grass. Some take dips in nearby ponds.

The ranch, 150 kilometres southwest of Edmonton, is in a picturesque part of Alberta known more for cattle and horses.

Horses live on Juuti’s ranch but yak’s dominate it, with close to 450 spread across his property.

It’s a business he fell into by accident nearly 25 years ago, after he bought a yak bull on a whim at an auction.

“I thought, ‘Well that's ridiculous. What am I going to do with one bull yak?’ So I bought a cow off a guy who'd bought several cows. And a week later she calved. Then it just kind of grew from there.”

Yak milk can be used on its own, or to make butter or soap. But the meat seems most popular.

“Most of what we do is, we sell meat from the animals to try to hit a natural market, just because they're easy to market that way and raised in that direction,” Juuti said.

When Juuti started raising yaks in 1996, little was known in North America about the meat. Now it’s being touted for its lower cholesterol and lower fat content when compared to traditional livestock.

Specialty stores carry Juuti’s yak meat, and Alberta restaurants have served his products. Business is booming, he said, and it has been tough to keep up with demand.

“In fact, we're struggling to come up with enough animals for slaughter,” he said. “It's taken a while to get there, but now all of a sudden we've got stores taking it.”

Yak meat in Canada is a niche market. It can’t be found in national grocery chains.

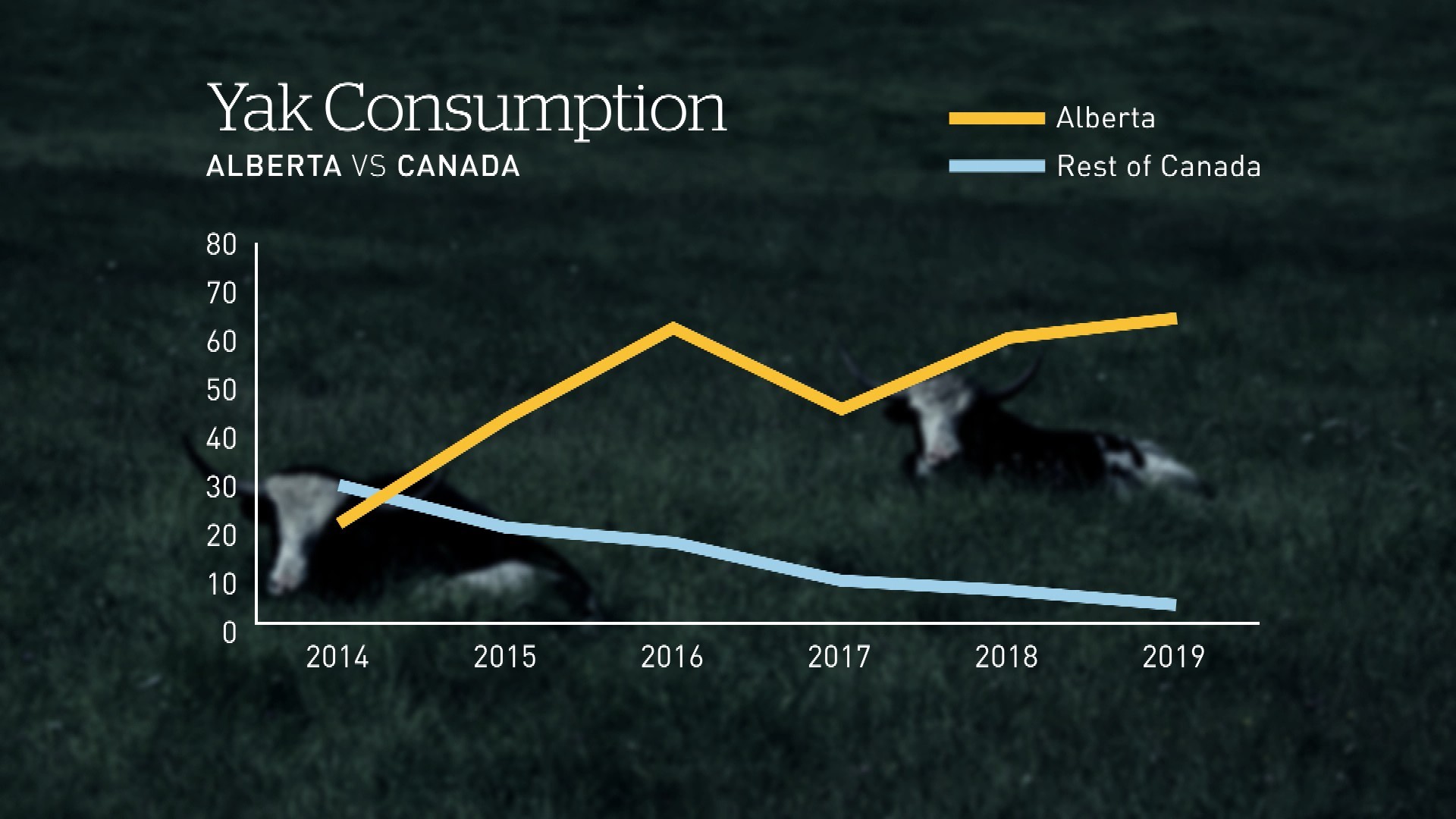

In fact, it appears to be somewhat of an Alberta phenomenon.

In the past five years, the yak slaughter has become more concentrated in the province. In fact, of the 68 animals slaughtered at provincially or federally inspected abattoirs so far this year, 64 were in Alberta.

“There's a lot of interest in traditional game meats from individuals who consume paleo diets,” said Amy Proulx, a professor at the Canadian Food and Wine Institute at Niagara College.

“So yak provides a really intriguing meat product that has a very good fatty acid profile and is high in protein.”

Yak meat is used in northern Asian cuisine and sometimes featured in restaurants looking for unique, locally sourced products.

“It's typically going to be high-end consumers in fine dining establishments looking for a really extraordinary culinary experience,” Proulx said.

Juuti thinks his decision to raise yak rather than cattle has paid off. He’s barely involved in calving, even in the winter.

“I find them way less maintenance than the cows and easier to deal with than the cattle,” he said. “So that's why I'd have a hard time switching back to cows from yaks.”

Yaks are native to the Himalayan region, which makes them a decent fit for the Alberta climate.

Life on a yak farm. Watch how Juuti's days are spent with his herd!

“They don't like the heat. If it starts getting much above 20 degrees they want to get out on a hill where they can get some wind, or else they like to go in the dugout to go swimming if it gets very warm.”

Juuti hopes the current demand for yak meat continues to be steady. He said he’s happy to help other farmers breed the animals to get their farms started.

Asked if he sees himself as a yak pioneer in Alberta, he laughed.

"I never thought about it," he said. "This wasn't the plan when we started … to have 400 head."