September 4, 2018

Teajai Travis' ancestor was a slave in the American South, and he's been looking to find more about his family history — that brought us to Southampton County, Va.

Travis, a Windsor, Ont. native, has been looking into his family's past for five years. He's always believed his family’s narrative was an important one in terms of North American black history in general.

"For a long time I've always wanted to find something incredible that I could speak proudly about," Travis said.

Over the course of multiple days, driving through states and provinces, Travis said he found that incredible missing story.

Virginia

In the small town of Courtland in Southampton County, Va., is the Southampton General District Court.

As of 2016, there were 18,057 people in the town: 62 per cent white and 35.4 black or African American, according to the U.S. Census.

The 184-year-old courthouse is on the town's main street and metres away from the Nottoway River. At the back of the parking lot is a tall monument, which you might miss if there were leaves on the nearby trees. The 1902 monument to Confederate soldiers was put there by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and moved to its current location beside the local court house in 1992.

The Confederate flag was removed from the site 3 years ago, according to the Tidewater News.

Inside, Rick Francis works as the circuit court clerk and local historian. He's been interested in local history since he was young, and his father gave tours about Nat Turner and the insurrection.

Turner led a slave revolt in 1831. He and other slaves killed more than 50 people. Francis' lineage is entwined with Nat Turner's. He's told the story of his family's survival many times. He even has a few jokes, "I think my family tree got trimmed a little bit."

Nat Turner and the Francis family

"My immediate family with my direct line was spared thankfully due to the actions of three slaves acting independently of each other during the 22nd of August, 1831," said Francis.

Francis settled in for the long story, which starts with the Travis family, Joseph Travis and Sally Francis being killed by Nat Turner, who owned him at the time. Sally Francis would be Rick's great, great grand aunt. Then more of his family was killed. His direct relative Nathaniel was warned by a 10-year-old slave that all the white people were killed his sister's house.

"Well, Nathaniel Francis didn't quite believe him, but he did take a horse and head over to his sister's house," said Rick Francis.

That left his eight-month pregnant great, great grandmother Louvina Francis alone. Another slave, Red Nelson, made it to her home before the slaves in the insurrection did, and helped hide her in a cubbyhole on the second floor.

"They're looking through the area, as family lore would have it, they reach in an even touch her petticoat, but she has fainted overhearing the overseer dying on the floor below," said Rick Francis.

Nelson said Louvina must be out in the 'tall cabbage' and they moved onto the next home. When she comes to she makes her way downstairs and Charlotte, a slave is looking through her hope chest holding one of Louvina's dresses.

Rick Francis explains how his family survived the Nat Turner Insurrection.

"Charlotte looks up and says 'Louvina I thought you were dead. If not you soon shall be,'" Francis said.

This is the last moment his family is saved by another slave during the insurrection. Ester, who had been Louvina's slave for a long time, pushed Charlotte out of the way and got Louvina to safety.

"To add even more strangeness to this, Nathaniel and Louvina would get reunited, in my family bible, first born child of that union, it's shown, born one month and seven days after the insurrection," said Francis.

His relative from Nathaniel and Louvina was born after the insurrection, four months after Nathaniel died. Francis said on one side of his family there are slave owners — the other side he can trace back to Abraham Lincoln's uncle, so he said there are abolitionists on the other side.

The drive through slave-owned land

In Francis' Prius we made stops along the Nat Turner path but did them in reverse order, starting at one of the few remaining structures from that era. We then went to the site where the ‘hanging tree’ was, and the area where his torso may be buried.

Eventually we made it to Nat Turner's first stop of the insurrection: the Travis plantation. In this home, every member of the family was killed, including an infant.

During the ride through the backroads of Virginia, Travis and Francis talked — with Travis wanting to know about land ownership, who lived in the area now and when Francis' family settled in Virginia.

As for land, Francis said it's become more diverse over the years: "more land rich and house poor." The area doesn't have a lot of employment opportunities other than farming or small businesses.

He too is researching his family. Thomas Francis was a part of Bacon's Rebellion, fighting against a governor who refused to retaliate to a series of attacks on frontier settlements by Indigenous people. The rebels lost and disappeared out into the countryside. Before 1749, it was technically illegal to cross the Blackwater river, but that's what his family did.

"My folks were not among the wealthy or powerful, they were just whatever's left after that," Francis said.

Records room

Back at the courthouse, Travis digs into old records to try and find anything regarding his family line. Eventually, he's able to find some notes on Richard Travis, but it doesn't state if Travis was white or black.

Among the shelves of books, there's a glass showcase with the history of Nat Turner, including comics, books, films, shackles, a broad axe and Turner's sword. Francis is enthused to continue talking about the Turner history.

"I don't know if anyone can be as excited to talk about it as I am," he said. "It involved family, so it is of interest to me, but a compelling story to me, because all the interactions, there's a whole lot of drama involved."

Although he loves talking about Turner, he said his daughter isn't as keen. Francis said while he's made peace knowing his relatives were slave owners, his daughter is having a hard time getting past that.

Francis is working with the local historical society and hopes to have an online tour made available.

"It will take everyone through the county and at each stop tell what happened and show at least what photographs we have of each site as it appeared in 1900," he said.

He notes there's still 'some heat' to the Turner story. Francis calls himself a Democrat in an otherwise Conservative county. He goes out and speaks about Turner and said there seems to be more anger in metropolitan areas.

"I don't know what that is. Maybe it’s that we all live together here, so we're more polite and civil to each other or try to be," he said.

Francis said there was some pushback, but it came from white people: "You know, 'why are you remembering this murderer?'"

He likes being a part of the discussion and showing people the local history. Francis doesn't want to impose his position to those he takes on tours. Instead, hoping they form their own ideas about what happened there 187 years ago.

Former Travis plantation

Teajai Travis took his first steps onto the soil his ancestors may have very well been enslaved on during his tour with Francis. Before exiting the car, Francis offered Travis a plastic bag to collect dirt in to take back to Canada.

"I'm also feeling quite powerful standing out here. I'm just looking out into these fields here and I'm remembering, like a blood cell memory exploding inside," Travis said.

The land is in Capron, Va, which isn't a far drive from Courtland, Va. It's mostly fields, trees and a few small homes, but something was missing.

"There's nothing out here to remind people passing by of the great tragedy that existed here," Travis said.

There's only one sign in the area that notes there were slaves in the area.

While on the land his ancestors may have been enslaved upon, Teajai Travis recites a poem.

Standing in the empty field, it was very quiet. Birds flew by, the wind moved through the bare limbed trees, and every-so-often a car would drive down the road. It was quiet, but felt unsettled for Travis.

"There's a piece of me that doesn't want to leave. There's a piece of me that feels like you belong here, the blood of your ancestors, this is your birthright," he said.

A lot of questions and thoughts came to him as he tried to reconcile what he saw, who he talked to and what would happen next.

"How do we measure the extent of how far we've come in seven generations,” he questioned. “I look around and think maybe we haven't come that far, but personally I've come full circle.”

Crossing the Mason-Dixon Line

We travelled like Teajai Travis' ancestor did. Crossed the Mason-Dixon Line and made our way into Pennsylvania.

In the early 1800s, Richard Travis Sr. — a free black man — and his wife Lucinda Travis (Francis) and family left Virginia. They made their way to what's now known as Stoneboro, in the northwest area of the state. Back then he bought 60 hectares of land for $2 U.S., and set up a community for runaway slaves.

He called it Liberia.

After 200 years only 0.40 hectares remain. It was overcast, cool and the sound of nature permeated through the air. On a small green hill off a country road sits the Freedom Road cemetery. Fugitives and freed slaves who died were buried here. There are a handful of wooden crosses that read, "EXSLAVE KNOWN ONLY UNTO GOD", and three stone markers.

"The wooden crosses are just here to represent people. I'm going to bet there's a number of people buried here and I'm going to even bet there's even more stones here that have fallen over and are buried," said Bill Philson, Executive Director of the Mercer County Historical Society.

It’s believed there may be as many as 80 people buried in the small plot of land, including Richard Travis Sr., who died in 1843. Stone markers have Civil War soldiers etched into them. To Travis' relief, those were black soldiers who fought for the north and for their freedom from slavery.

"It's incredible to come out here. It's beautiful for one thing. The story is crazy. The story is wild. To think that all these years ago, my oldest known ancestor left Virginia and came here and purchased this huge piece of land, 150 acres for two dollars. That's mind blowing," said Travis.

A black American settlement

Liberia was Mercer County's first black settlement. Historian and author Roland Barksdale-Hall has extensively studied the area. Slaves who made it here were able to get an education, have a business, and make their own money.

"Liberia meant land of freedom," Barksdale-Hall said.

For many this was their first chance at owning land in America. He said the settlement was groundbreaking and led the way for other free settlements in Mercer County.

Although records from that era are scarce, Barksdale-Hall found a day book. It gave a look into the lives of free black citizens who were forging their own path. The day book shows some transactions between the Travis' and a merchant. In it, the Travis family traded maple syrup for bullets and gunpowder, as well as cotton and cloth.

In Mercer County, there was a shop that only sold items made through free labour. The Zahniser Brother's Free Goods Store would cost about a third more, but people would go there and pay more so they wouldn't have a hand in supporting slavery.

Bill Philson, the Executive Director of the Mercer County Historical Society recounts some of the tales of other residents that lived in Liberia, Pa.

The settlement is rife with folklore. There was one runaway slave who became a legend in Mercer County. Auntie Strange made multiple attempts to escape her owners. She was caught and had her fingers cut off as punishment for running away.

Philson painted Auntie Strange as a stubborn woman who wasn't going to put up with poor treatment and said she, "left again and came up here and she wouldn't leave — this is where her home was.”

Barksdale-Hall imagined what it was like for her to go to Liberia, a place of freedom where she could see African Americans in a leadership role after persisting after such hardship, pain and suffering.

Underground Railroad

Liberia was more than a place for African Americans to find opportunity, it also helped fugitive slaves find momentary safety. Travis, along with a few other residents were conductors along the Underground Railroad.

It's not known how many people made their way to freedom through Liberia, because the act was illegal.

"Liberia was an anchor to freedom," said Barksdale-Hall.

The area allowed those looking to move further north different ways to escape to safety. Meadville, Pa., Erie, Pa., and Ashtabula, Ohio would take freedom seekers to Lake Erie to cross into Canada.

Even though it was Pennsylvania, it didn't mean everyone supported the freedom of slaves. There was interracial cooperation along the Underground Railroad. Even still, the county was divided into those who supported slavery, those who were against it and "a middle majority who just didn't give a damn," said Philson.

Fugitive Slave Act

There were about 24 cabins with black families settled in Travis founded Liberia until the 1849, 1850 Fugitive Slave Act was passed. The new law allowed slave owners to go north of the Mason-Dixon Line, look for former slaves and return them to the people who previously owned them.

Both historians shared stories about slave catchers who came to the area. Philson recalled one time where two women and one young man were captured, and while en route to jail the women distracted the slave catcher and the young man was able to escape.

Slave catchers also knew how important religion was to the African American community. They used that knowledge to their advantage. There was a newspaper article Barksdale-Hall found that said bounty hunters captured individuals on Sunday, because they knew they would be at worship.

Not long after the Fugitive Slave Act passed most black families in Liberia went north to Canada, including the Travis family.

Lost legacy

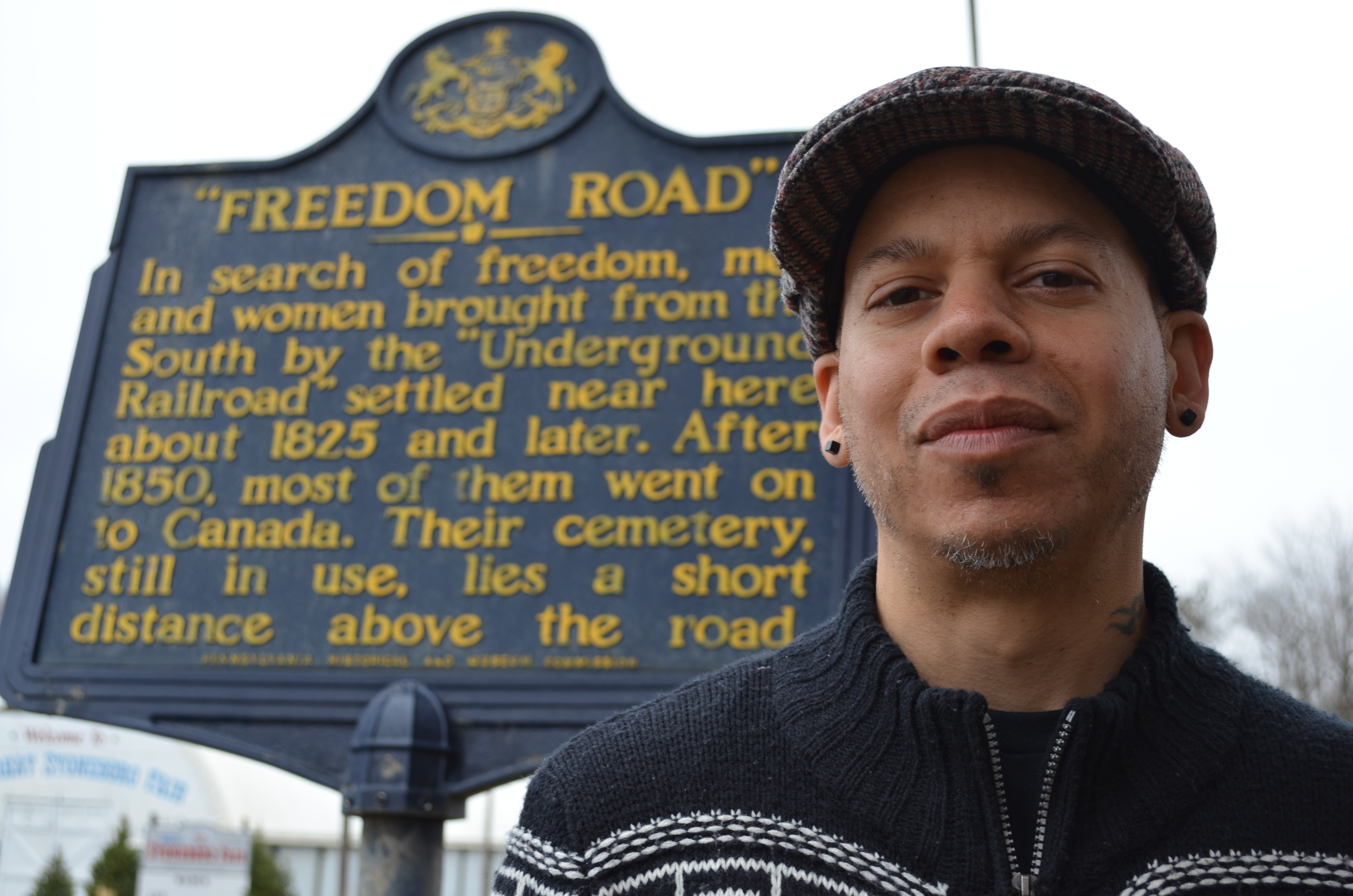

Teajai Travis came to the area once before. He wasn't able to find any information or talk to anyone, but did find the Freedom Road marker near the cemetery. There's a wooden post just before the path leading into the graveyard. A piece of paper inside a glass frame explains its history. There's no mention of his ancestors. That day he shoved a piece of paper with his family's history into the frame.

Back on the land now, someone has added this piece of paper to the post and held it safe with a plastic cover. Even though Richard Travis Sr. is known to those who come to look, it won't be enough for Teajai.

"If there's a possibility to raise some fund with the community here to get some sort of monument, some sort of marker that allows my relatives to have somewhere to go home to, that's huge," he said.

The journey from Virginia to Pennsylvania turned into an emotional rollercoaster for Travis.

"Standing on the soil at that plantation, I didn't feel much in that moment. Coming on this land here, I feel the liberation," he said. "There's parts of me that feels like yea, this is where I'm supposed to be. I wish my whole family was here too. I'm excited that I can bring a little piece of this back home to Ontario."

Home to Canada

After the Fugitive Slave Act the Travises moved from a American black settlement to a Canadian one. The family ended up in Buxton, Ont., about 80 kilometres northeast of Windsor, Ont. It became home to them and many other American families.

"Being in Buxton brings it full circle, because this is where the family is," Travis said. "When we were in Virginia and Pennsylvania, like that's where the family was, but this is where we are now."

Today the area is a mix of homes and farmland — back then it would have been a forested area. The area was well documented in news articles, said Bryan Prince, historian at the Buxton National Historic Site. People during that time travelled to America and back to Canada — up to Toronto and Niagara.

"The church connections are one thing that binds the two countries together," he said.

Many would come for annual church conventions then travel back and forth through America and keep in touch. The word about Buxton even made it to the deep south.

"There's a big exodus in 1850 after the Fugitive Slave Law. But certainly there were a lot that came from a lot of places in the south, including the deep south. Virginia, Louisiana, very deep south, where the founder and the first group of slaves came from. So scattered throughout Alabama and all over."

Buxton was founded in 1849 to be a black settlement. Prince claims the 3600 hectares of land supported 1,200 people at its peak during the American Civil War. A group of antislavery sympathizers pooled their money together to buy the land and then divided it into 20 hectare lots.

Bryan Prince, historian at the Buxton National Historic Site explains what it was like for new black settlers in Buxton, Ont.

When families first arrived they could buy one 20-hectare lot — it cost $6.25 per hectare. There was comradery between those who lived in Buxton and new arrivals. As people would move there the already settled families would help clear land and assist with building homes.

"Certainly it was a lot of back breaking labour clearing, this would all been forested," Prince said.

He went on to say many who came up America lived scattered among the general population. Often they would have the lowest paid jobs and face a lot of discrimination — Buxton was different.

"They had hoped that by having a distinct pioneer community that all of the occupations and aspirations involved in building a new community that the blacks could be a part of," he said. "So it wouldn't just be the farm labourers. They would be the school teachers, the shop owners, the blacksmiths, all of those different occupations."

In the heart of Buxton there were blacksmith shops, stores and a Temperance hotel as liquor was not allowed within the settlement.

Members of the Travis family worked in agriculture, but also helped build the school house and the Methodist church that still stands today.

Opposition from the whites

Although the settlement was created specifically for the black community, there was a military road that went through the town — and along that road lived white families. Their children went to a township school. Prince said black children were refused entry because of the colour of their skin. So, they built their own school.

"They got teachers from Knox College in Toronto, qualified teachers, so the level of education was much higher than it was in the regular township schools," he said. "So little by little the white families start to send their children to the black school. So much so that eventually the white school has to close, the township school closes and the black school is the only one in district."

One of the teachers from America as a child and lived with his aunt and uncle. James Rapier was one of the first school teachers in the last incarnation of the school house. He would move back to Alabama after the Civil War and become a congressman.

"A lot of people who were educated here in Canada that took those skills back to the United States after reconstruction and became the congressman, became the school teachers, the principals in schools, doctors, a lot of very important leaders in that reconstruction period," Prince said.

Sharing his story

During this journey Travis went through a lot of different emotions. He said being able to take dark, rich dirt from the Virginia farm, provided him some closure, however, he still felt pain and anguish while reflecting on what his ancestors endured.

"It was powerful to look at that as a person who is born liberated and with a great deal of privilege, "Travis said. "The opportunity to meet people who lived there and are entrenched in that culture was very interesting."

Meeting Francis in Southampton gave him a new perspective.

"We accept slavery as something that happened, but we moved past it," Travis said. "It's very easy to move past it as a person who owned slaves, because we don't own slaves anymore and we're doing work to reconcile in the best way we know how, but it doesn't even scratch the surface of the work that needs to be done."

It's important for Travis to talk about reparations. He said it's critical to understand how the dominant white culture enabled power and privilege to negatively affect the economic situation for everyone else.

"These conversations are important. As we travelled into Pennsylvania, you walk just north of that Mason-Dixon line, and you're like, well ok, there were people here willing to fight the good fight, but it doesn't excuse or pardon the extreme racism that was ingrained into that culture." he said. "Racism that is still here today, regardless of how far we say we've come."

Travis wants the story of his family to be one that's told inside classroom throughout Canada and America.

"Because that's huge to know that one of your ancestors founded a black settlement, known as a fugitive slave town, "he said. "Hooking up people who were escaping slavery with plots land so they could farm and better their lives and then move into the future in a meaningful way. That's huge. That's a huge story."

The records he was able to find in Mercer County are another piece to the puzzle he had been searching for. He now knows more about the life of Richard Travis Sr. and plans to pass down the story to future Travises.

Liberia was a place where, for a time, black citizens could be what they wanted to be, however, after that opportunity was taken by new laws, families began fleeing to Canada to seek out a similar situation.

"Being inside Buxton, this was and is Freedom Land, "Travis said. "We're going to come to this space and you're going to be whatever you have the capacity to be."

Teajai Travis recounts his time looking for his family roots and his intentions with the knowledge he's gathered going forward.

His father Terry Travis Sr. and cousin Rodney Jones joined Travis on his return to Buxton. Jones said although he never lived there his family roots are firmly planted in the Buxton soil.

"Walking through the graveyard there's just so many Jonses'," he said.

Jonses would come up with his dad to visit regularly. But since he's passed away he comes up to be a part of the Buxton Homecoming celebration.

The community celebrates Buxton's past. Descendants of families that once sought freedom there return to celebrate the origins of the settlement’s creation. The four-day event now draws thousand of people.

"Coming up here and the fellowship that you get from seeing people, hugging them, seeing somebody that you seen who was ready to give birth last year, they come here with their children and the comradery."

Teajai's father is very proud of all the work his son put into learning more about his family's history.

"I liked all the history he brought back, because before this I didn't know much about it until my son got out there doing it," he said.

Travis still hopes to bring his family out to see Liberia. He said pictures are one thing, but putting your feet on the same plot of land your ancestors worked hard to get is something entirely different and more meaningful. He also wants to make sure that history is never lost.

"One of the things I brought back that I spoke to some of my family about was the possibility of us pulling together and putting in a monument there," he said. "Some sort of tombstone for Richard Travis Sr., so the young people coming behind us have a place to go home to if they so chose to."

It's not just physical reminders for Travis. There is even more work he hopes America is open to when it comes to discussing slavery. He points to Canada's efforts with the Truth and Reconciliation commission and our Indigenous population.

"In the United States of American they're not even talking Truth and Reconciliation with Indigenous people and they're not even talking Truth and Reconciliation with people who were enslaved to build their powerful country. That's the reality of the circumstance. So I don't leave any of this as a victory. I don't feel like we've won by gathering this information, it just opens up the rabbit hole to jump down into and grind into really getting some answers."