October 27, 2018

I

The Halifax Explosion. Hurricane Hazel. The Great Vancouver Fire. All of these disasters stick in our collective memory.

But chances are you've never heard of the worst maritime disaster in the Pacific Northwest.

On Oct. 25, 1918, the SS Princess Sophia, a Canadian Pacific steam ship, sank in the Alaska Panhandle. All 364 passengers and crew died. There were Americans and Canadians on board, but the majority came from Yukon. In fact, the disaster wiped out 10 per cent of Dawson City’s non-Indigenous population.

And yet, a century later, the SS Princess Sophia disaster is forgotten — even in Yukon. That's because it struck just weeks before the signing of the armistice for the First World War. Although newspapers reported on the Sophia's sinking, headlines anticipating and eventually heralding the end of the war ultimately crowded it out. Around the same time, the Spanish flu hit the west coast.

Another reason the Sophia is forgotten is that none of the victims are buried in Yukon.

Historian Ken Coates, co-author of The Sinking of the Princess Sophia, was born and raised in Yukon, but didn't learn about the Sophia until he was researching a paper about the First World War for a third-year history class at the University of British Columbia.

Coates says the sinking of the Sophia had a big impact on Yukon after it had already been through so much during the First World War. Yukon had the largest per capita military enrolment of any jurisdiction in Canada. More than a thousand people enlisted in the war, and close to 100 people died.

The ship disaster "really had a dramatic effect on the sort of spirit of the place," said Coates.

"They've already been beaten a bit by the war and then this comes along and takes some of the most important citizens with it."

II

The SS Princess Sophia left Skagway, Alaska, on Oct. 23, 1918, bound for Vancouver and Victoria.

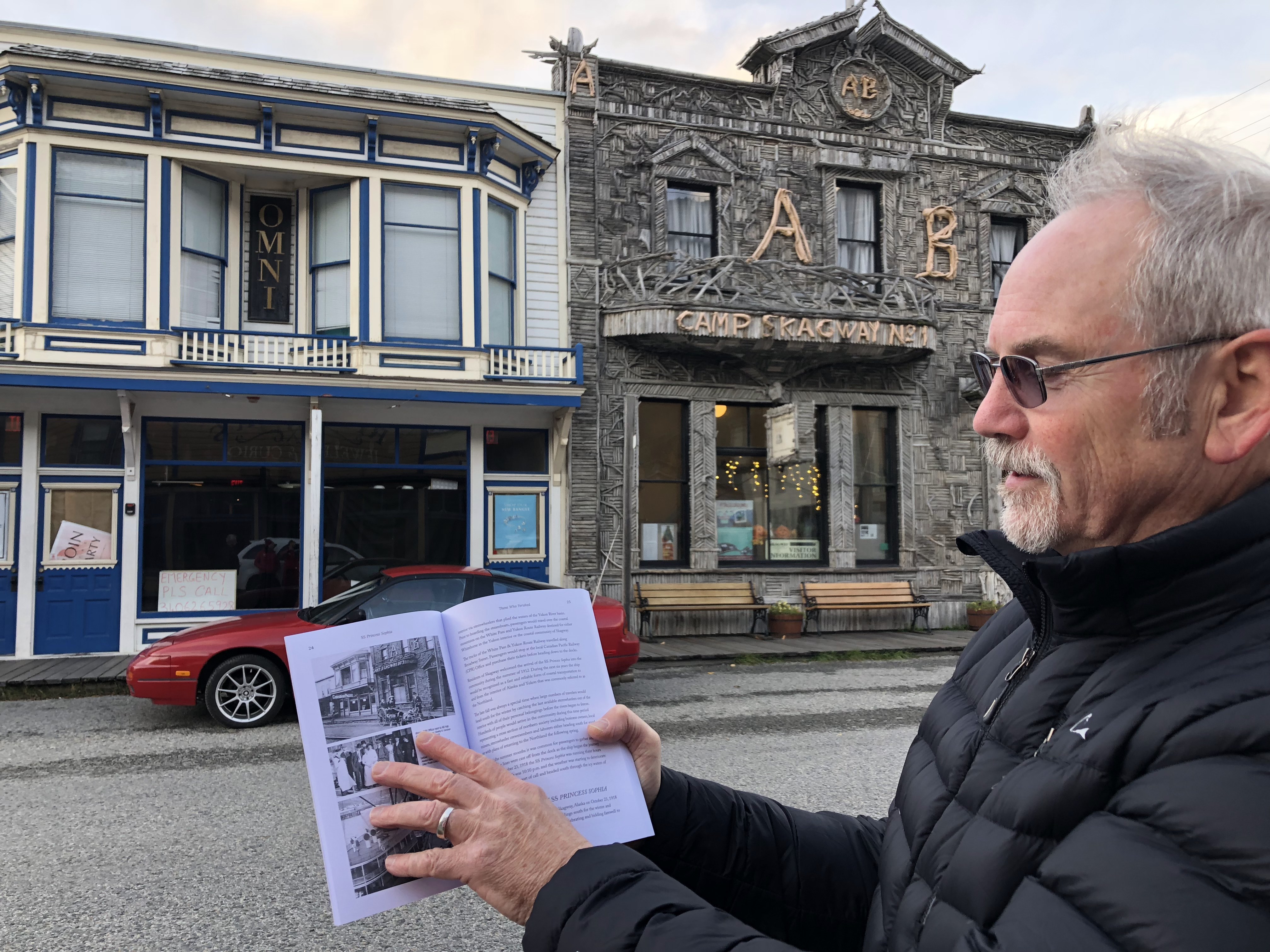

Skagway, with a population of about 1,000, is nestled at the top of the Chilkoot Inlet in the Alaska Panhandle, and is surrounded by mountains. It's always been an important transportation hub for the North. In 1898, it was the start of the Chilkoot Trail, the gateway to the Klondike Gold Rush. Today, it's a popular stop for cruise ships.

In October 1918, Skagway was lively. At this time, the rush was heading south, like it did every fall. Travellers would have sailed up the Yukon River on sternwheelers from Dawson, and then jumped on a train from Whitehorse.

It was so busy that John F. Pugh, the customs collector in Juneau, arrived in Skagway to help control the crowds. Once that job was done, Pugh got ready to get on the Sophia heading back to Juneau.

There was a mass exodus each fall for Vancouver, Victoria, and the lower 48 U.S. states. But before saying goodbye to friends for the winter, there were dances and parties in Skagway — a custom that hasn’t changed, according to Skagway's current mayor, Monica Carlson.

"The seasonal pattern of life in Alaska and the Yukon remains true," said Carlson. "Every fall, we wave goodbye to our friends and families heading south for the winter via the Alaska Marine Highway."

The SS Princess Sophia finally left Skagway on Oct. 23, 1918 at 10:10 p.m. — three hours behind schedule. The reason for the delay was because Capt. Leonard Locke had to canvass Skagway for new crew members after several came down with the flu.

Capt. Locke sailed down the Lynn Canal at full speed. One theory about his haste was that he was trying to make up time, said David Leverton, the executive director of the Maritime Museum of British Columbia.

But it was extremely snowy out, and Leverton said the ship’s crew mostly did their dead reckoning by blowing the ship’s whistle and counting the seconds to the back echo to determine where they were in the Lynn Canal.

In the middle of a snowstorm, the ship was at least one nautical mile off course.

"By the time they actually reached the vicinity of Vanderbilt Reef, it was just shortly after 2 a.m. in the morning, so it was pitch black," said Leverton. "They were in a blinding snowstorm, heavy seas."

Vanderbilt Reef was awash with an extreme high tide, and there was no light on it. "There's no way they could have seen it," said Leverton.

And so, just after 2 a.m., the ship hit the reef at very high impact.

"The bow lifted out of the water and, with a horrible grinding and tearing, slid up and onto the rock," writes Coates in The Sinking of the SS Princess Sophia.

Leverton said there was quite a bit of damage to the starboard side.

Not much is known about what happened on board, but a letter written by passenger John Maskell to his fiancée, Dorothy Burgess, in Manchester, England, gives a glimpse of what passengers experienced.

"My Own Dear Sweetheart, I am writing this dear girl while the boat is in grave danger. We struck a rock last night which threw many from their berths, women rushed out in their night attire, some were crying, some too weak to move, but the life boats were soon swung out in all readiness, but owing to the storm would be madness to launch until there was no hope for the ship."

He wrote that "the boat might go to pieces, for the force of the waves are terrible, making awful noises on the side of the boat, which has quite a list to port."

"During that first day, they really felt that if the ship was going to come off the reef, it was going to happen then," said Leverton.

"They had seven different rescue ships ready to come to the aid of the ship if it foundered off the reef. But what ended up happening was that it settled down on the reef."

Capt. Locke's barometer predicted that good weather was on its way. He told the crews on the rescue ships to leave and go rest before a rescue attempt the following day, once the weather had improved.

Around 5 p.m. that day, the sea grew rougher still, and finally lifted the Sophia off the reef, where it had been sitting for almost 40 hours.

An animated interpretation of how the sinking of the SS Princess Sophia happened (Eric Ouimet/CBC)

Then the ship turned into the sea, which ripped open the starboard bow.

Water started to pour in. At 5:20 p.m., wireless operator David Robinson sent one of his last messages to the coast guard ship Cedar. "For God’s sake hurry, the water is coming into my room."

The rescue ships returned the next morning. The sea was calm. But all they could see of the SS Princess Sophia was the foremast.

Bodies floated in the water. Their watches had stopped at 5:50 p.m.

III

Ralph Zaccarelli has a personal connection to the SS Princess Sophia — his grandfather, John Zaccarelli, was on board.

In October 1918, John Zaccarelli was on his way to Oakland, Calif., to join his wife and children. He had immigrated from Italy to Dawson City during the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush, and opened a number of stores. After 20 years, he decided to close up shop and leave the North.

Zaccarelli had a ticket on an earlier steam ship, but gave up his seat so a family could travel together, said his 73-year-old grandson.

After Zaccarelli's death, his widow moved back to Dawson City with her sons and eventually married a man named Charlie Vifquain, who lost his wife and daughter on the Sophia.

"You never really realize how many people went down on it. You know of your original relative or whatever but you don't realize how many families went down," Ralph Zaccarelli said.

The biggest family on the Sophia were the O'Briens from Dawson City: William and Sarah and their five children, Grace, 14, Pearl, 10, Robbie, 8, Billie, 6, and Ruthie May, 2.

Historian Ken Coates said the O'Briens were very active in Dawson City society and "pillars of the community." William was in local politics and well-known for his singing voice. Sarah was involved with the church and other community groups.

There was one man on board whose death may have had a direct impact on Yukon’s economy at a time when it was in a dramatic decline. That was Capt. James Alexander, who had been developing a mine on Tagish Lake.

"The story was that he was on his way outside and he had negotiated a million-dollar investment to get the mine going," said Coates.

"That was a lot of money back in 1918. You could have very well seen a substantial mining operation on Tagish, which would have really revitalized Carcross and perhaps turned it into a fairly substantial-size community."

There was one lone survivor of the disaster — an English setter that may have belonged to Capt. Alexander. In The Sinking of the Princess Sophia, Coates writes that the dog was found, two days later, in Auke Bay, outside Juneau, "half starved and covered in oil."

While a lot of Canadians may never have heard of the SS Princess Sophia, there have been attempts to raise awareness of this maritime disaster.

Earlier this month, a memorial was held in Skagway on the very pier the Sophia departed from a hundred years before. Jeff Brady, part of Skagway’s SS Princess Sophia committee, tossed flowers into the waves crashing into the pier. About 70 people attended the memorial.

Leverton says the centennial is a chance for Canadians to learn about this often overlooked part of history, and "to appreciate the people, the crew members, the families, everyone affected by the story" and ensure they are being dutifully remembered.

"That's the most important part of the story."