October 5, 2020

The following story is based on material from the podcast Recall: How to Start a Revolution, which traces the pivotal events of the October Crisis, which began 50 years ago this October. Listen to the podcast and subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Podcasts.

Late in the afternoon on Aug. 29, 1964, François Schirm and a crew of four aspiring revolutionaries climbed into a stolen Pontiac and headed for downtown Montreal. Their goal that day: to rob a gun shop to supply their liberation army.

They started out from Davidson Street, on the east side of the city, but before reaching their destination, they stopped at a tavern. They ordered a dozen beers to summon the courage to go ahead with their plan.

Schirm's group called him "The General." About a decade older than his fellow militiamen, he was 6' 2" and struck an imposing figure. His men trusted him with their lives.

An emigré from Hungary who had grown up during the Second World War, Schirm learned his skills in the French Legion, where he became a sergeant. While living in Montreal, he had experienced the everyday humiliations suffered by many Québécois at the time — being told to "speak white" (meaning English) in a majority French province, doing menial jobs and not being able to earn enough to sustain a family.

Schirm was in search of a cause, and he had found it in the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), a clandestine movement aimed at the liberation of the Québécois.

In 1963, the group began a campaign of bombings to denounce Anglo exploitation. Schirm had no interest in bomb-making, but he had military experience, which is why he had decided to create a revolutionary army, which trained in Saint-Boniface, about 150 km northeast of Montreal.

The five men made for an unlikely army. Marcel Tardif, 22, had worked for the Royal Canadian Navy. Gilles Turcot, a father of five, had been part of a Scottish regiment, the Black Watch. Twenty-year-old Edmond Guenette was married and a father of two. Cyriaque Delisle, 26, worked in the ministry of defence.

The revolutionaries hoped that media coverage of the robbery might scare the Queen and derail her visit.

All of them had experienced discrimination as a result of being francophone.

"On a daily basis, everything had to be in English," Delisle would later say. In the army, where he’d also worked, Delisle had seen bilingual and anglophone colleagues get promotions while he himself couldn't get ahead.

Delisle had only joined the gang earlier that day in August, after their original driver bailed on them. The other four had heard about Delisle's Quebec nationalist sympathies, so when they knocked on his door asking if he wanted to take part in a political operation, Delisle had not been hard to convince.

He just set two conditions: that there be no violence, and that after the robbery, he would never see them again.

Their target was the International Firearms Company on De Bleury Street, close to De La Gauchetière. The giant sign by the door promised shotguns, rifles, pistols, outboard motors, ammunition and shooter’s accessories at the lowest prices in Canada. The group's goal was to steal enough weapons and munitions to sustain their continuing operations.

The timing of the heist was no coincidence: Queen Elizabeth was set to visit the province a few weeks later, and the revolutionaries hoped that media coverage of the robbery might scare the monarch and derail the visit.

As Schirm gave final instructions to his men, he had one last bit of advice: "Personne ne tire sans raison valable." Nobody shoots without a valid reason.

At 5:55 p.m. sharp, Schirm and Guenette walked to the front door of the store while Delisle drove the Pontiac to the back lane with Turcot and Tardif. As Schirm and Guenette entered, everything was still going according to plan.

Schirm would ask the store clerk to see an M1 rifle. He would then turn the weapon on the clerk and declare: "Armée révolutionnaire du Québec, vos mains sur le comptoir et que personne ne bouge!" (Quebec's revolutionary army — put your hands on the counter and nobody move!) Within a few minutes, and hopefully without any casualties, they would have stolen enough weapons to start their army.

Instead, the operation took a tragic twist. By the time it was over, two people were dead.

During its lifespan, the FLQ's activities involved hundreds of bombings and other violent actions, which injured dozens and led to 11 deaths (four of them FLQ members themselves). The group is arguably best known for the kidnapping of British diplomat James Cross and Quebec labour minister and deputy premier Pierre Laporte, who was later found dead, during the 1970 October Crisis. But there was a string of prior events that not only signalled the seriousness of these Quebec separatists but also tested the legitimacy of their approach — in the eyes of the public and the families of FLQ members.

LISTEN | The story of François Schirm:

The bloody robbery of the International Firearms Company, orchestrated by François Schirm, was one such case.

For many people, Schirm was a terrorist with no pity for his victims. His supporters admired him for his principles. To his daughter, Sylvie, he was a man with a complicated past who taught her to stand up for what she believes in.

"My dad was a dreamer," said Sylvie Schirm.

But that idealism led to carnage on that day in 1964, a fact that wasn't lost on Régis Fortin, one of the police officers who responded to the robbery at the International Firearms Company.

Fortin's son, Daniel, is quite blunt about it: "My whole family changed that day."

II.

In a Radio-Canada interview he gave in his later years, Schirm described himself as part of a generation of kids "who were poisoned" by the Second World War.

Born Ferenc Schirm in Hungary in 1932, he was an only child. During the war, while Schirm's father fought in the Hungarian army, he and his mother became refugees in Austria. Once the war ended, the family moved back to Hungary. In 1949, as the Soviet Union was consolidating its power over his native country, Schirm sought refuge in France, where he changed his name to François and signed up to become a parachutist commando in the Foreign French Legion.

After being deployed to quell anti-colonial uprisings in Indochina and Algeria, Schirm came to identify with the people he was fighting against. Of his time in Algeria, Schirm would later say, "it was not a war, it was a killing." And so in 1956, he decided to leave the army.

Around the same time, Schirm started to correspond with a young Hungarian woman named Elizabeth, whose family had moved to Canada. (He’d found her through an ad in a newspaper for Hungarians abroad.) He eventually moved to Montreal to meet her.

When Schirm arrived in Montreal in 1957, Quebec was living in the era of Premier Maurice Duplessis, a period that later came to be known as the Great Darkness. The province was mired in poverty, with inadequate health care and education. More than half of French Canadians had only attended elementary school, and only six per cent had a university degree (compared to 12.5 per cent among Anglos). Although French speakers comprised the majority linguistic group, they ranked 12th out of 14 in terms of income, surpassing only Italians and First Nations.

Schirm married Elizabeth. Together, they had a daughter, Sylvie, and created a life for themselves in the "Hungarian ghetto of Montreal," which is how he described the close-knit community, which seldom integrated and where he didn't see himself fitting in.

Schirm found odd jobs in construction, as a security guard and a night watchman, but for the most part, he struggled to put food on the table. There wasn’t a lot of demand for an ex-commando. Ultimately, his marriage fell apart under the strain, and Schirm wound up isolated in a country that didn’t feel like his.

"He sympathized with the plight of the French-speaking Quebecers," said Sylvie Schirm, who was a toddler at the time and is now a well-known lawyer in Montreal. "When he split up with my mom, he was very lonely and he made friends with a lot of French-speaking Quebecers who were involved in the movement of the revolution."

By 1964, Schirm had become involved with the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN), whose aim was to make Quebec an independent country — a revolutionary position in those days. The RIN, however, wanted to use democratic means to achieve its objective, an approach that Schirm eventually found limiting. He started to look to the FLQ.

In retrospect, Schirm's drift toward a paramilitary organization was not that surprising, said his daughter.

At that point, the underground movement was barely a year old. It had started in 1963, following an uproar over a declaration by the CEO of CN Rail against hiring French Canadians at the top level. On the night of March 7, 1963, bombs exploded on three military barracks in Montreal. Although there was limited damage, activists painted three letters in red on the walls: FLQ. It was the opening salvo for a movement that would last almost a decade.

Schirm decided to create an offshoot of the FLQ — the Armée révolutionnaire du Québec. In retrospect, Schirm's drift toward a paramilitary organization was not that surprising, said his daughter.

"You had this man who had military training," Sylvie said. "So to him, the solution was military."

This ultimately led him to undertake a raid for weapons at the International Firearms Company in August 1964.

III.

The plan went off the rails almost immediately. After Schirm and Edmond Guenette entered the store, the two revolutionaries announced themselves, but the shop manager, Leslie McWilliams, misunderstood what was happening. He asked Guenette to lower his gun, but the young man ended up firing it, killing the 58-year-old McWilliams.

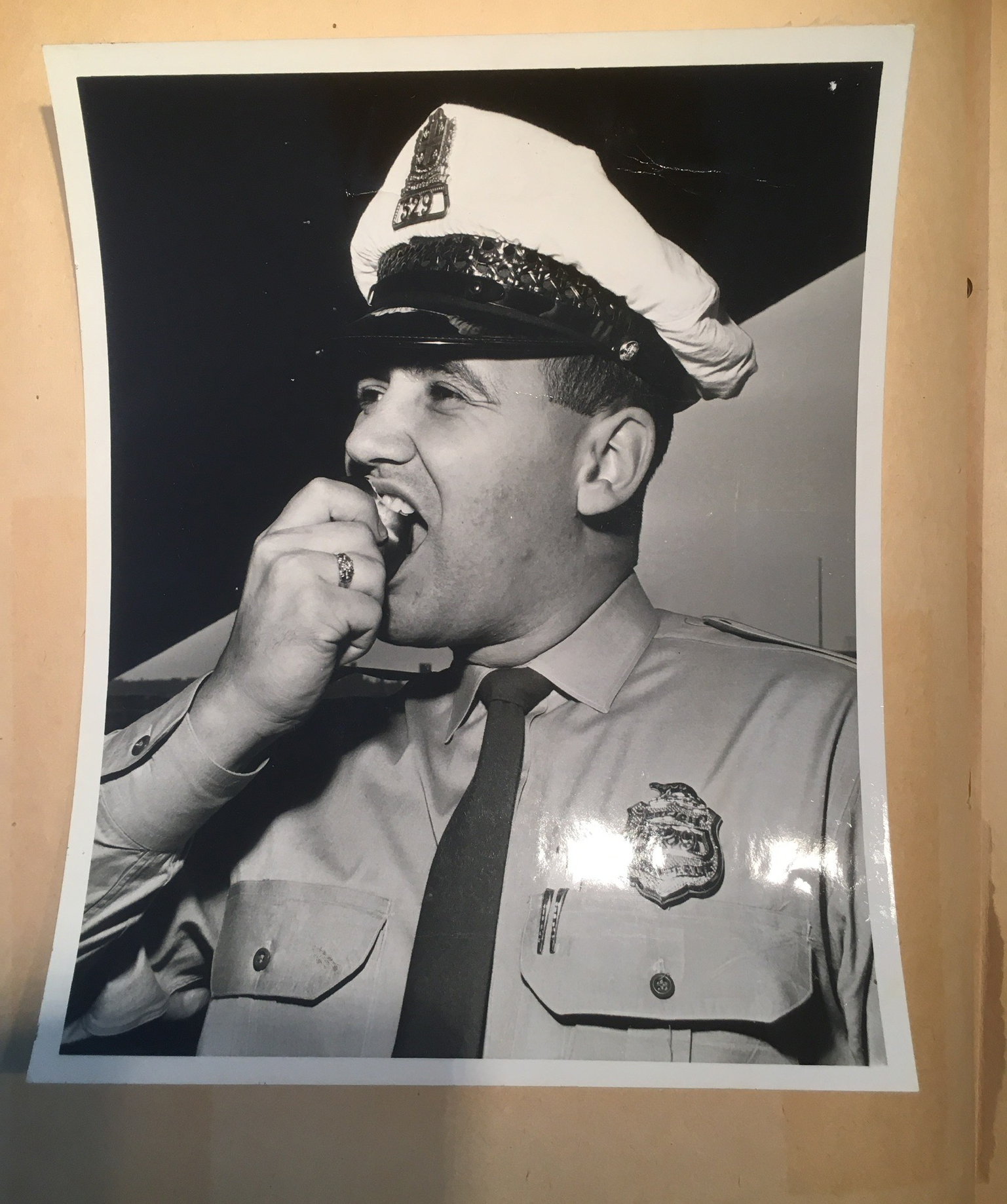

Two officers were answering a call nearby when they received notice of the situation at International Firearms. Régis Fortin and his partner, Raymond Dufault, ran to the scene and saw Schirm's men coming out of the back of the shop with arms full of guns.

"They were putting a bunch of them in the trunk of a Pontiac when they saw the cops," said Fortin's son, Daniel. That's when they started shooting. The police returned fire and rushed inside. In the confusion, Fortin and Dufault saw a store employee coming from the cellar with a rifle. Despite their pleas for him to stop, the man kept approaching — and the bullets kept coming.

Alfred Pinisch, 36, fell to the ground, pleading that he was not one of the robbers ("No, no, no, I am an employee, I work here!").

According to the coroner's report, Dufault was the one who shot Pinisch. But Daniel Fortin said that "on numerous occasions, my dad said it was him."

The heist was the lead item on the front page of Montreal's Le Devoir newspaper, which quoted the police as saying, "These are not ordinary bandits, they have revolutionary ideas."

WATCH | A news report on the August 1964 robbery at International Firearms:

Daniel Fortin said that the confrontation at International Firearms transformed his entire family. "My dad changed," he said. "He started suffering from alcoholism. He became violent ... it influenced our whole life."

In the weeks and months following the shootout, Daniel's dad started drinking. He started gambling and became abusive with Daniel's mother. Régis Fortin even did prison time for assault. By 1968, he had been demoted and forced to turn in his badge. He was less than a decade into his career.

At the root of his Fortin's problems was a deep guilt for killing an innocent man, said his son.

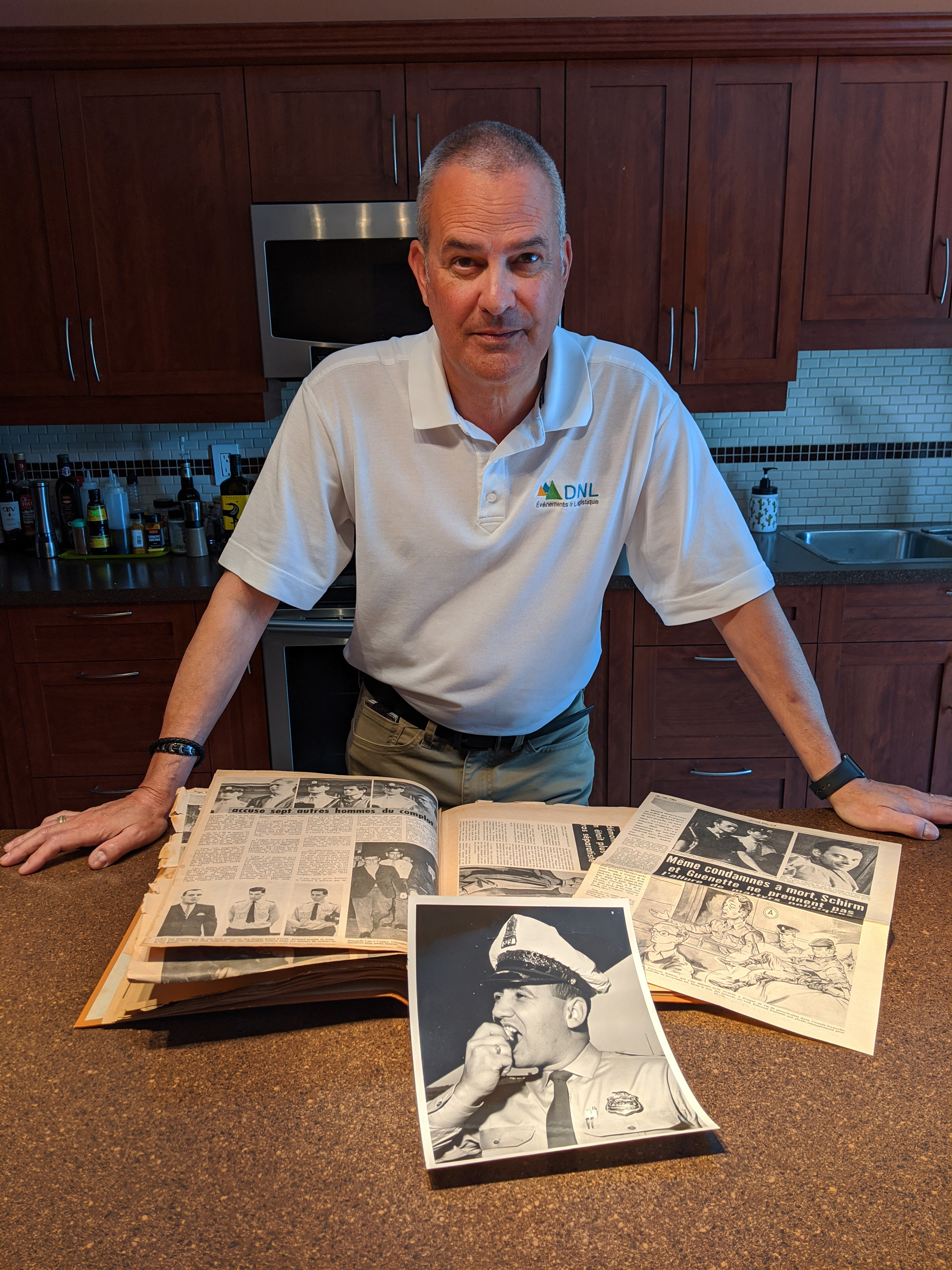

During a recent interview with CBC/Radio-Canada at his home near Montreal's Atwater market, Daniel Fortin shared newspaper clippings of highlights from his father's police career, as well as reports about the robbery and the subsequent trial.

One photo shows François Schirm on a stretcher, shortly after his arrest, smiling and making the victory sign. To Fortin, it was a sign of Schirms lack of empathy for his victims. "He really didn’t care — he was trained for that."

Following the attack, Schirm and his gang were arrested. Cyriaque Delisle, the getaway driver, was eventually forced to plead guilty, and received life in jail.

Schirm and Guenette would be tried together nine months later. Since no lawyer wanted to argue his case, Schirm chose to represent himself. (Guenette did have a lawyer, who advised him to plead guilty, which he did.)

Schirm characterized the death of the two gun-shop employees as an accident, not a murder. During his closing arguments, he told the court how as an immigrant he felt a connection with the Québécois, a group exploited as cheap labour, as he was. His speech lasted an hour and a half and ended with him saying, "Vive le Québec libre."

Schirm and Guenette were sentenced to death in May 1965. Their sentences would later be commuted to life in jail.

It took just 45 minutes for the jury to arrive at a guilty verdict for Schirm and Guenette, both on the charge of capital murder. The presiding judge, André Sabourin, took the opportunity to rip into the would-be revolutionary. "You have believed in and lived by violence. You have had no pity for men, women or children. And now you are getting what justice holds for you. You will be hanged by the neck on October 22nd."

As he heard the sentence on May 21, 1965, Schirm smirked, turned to his girlfriend and yelled "Vive le Québec libre!" one last time before being carried away by the guards.

The next day, while noting Schirm's arrogance, Montreal daily La Presse published a transcript of his address to the jury.

Schirm and Guenette were among the last people in Canada to be sentenced to death (although their sentences would later be commuted to life in jail).

That was not the end of the FLQ cause. More acts of terrorism and trials would follow.

The 1968 trial of Pierre Vallières for manslaughter associated with two bombings further contributed to the FLQ's notoriety. In a book published during the trial, Vallieres compared the feelings of injustice and humiliation of the Québécois to that of Black Americans.

LISTEN | Tapping into the revolutionary anger of the Black Panthers and others:

All of this led to the crisis of Oct. 5, 1970, when an FLQ cell kidnapped British diplomat James Cross, starting a chain of events that would lead to the abduction of another political figure, Quebec labour minister Pierre Laporte (who was found dead a week later), and the imposition of martial law.

Hours before the federal government imposed the War Measures Act — a little-known provision allowing police to search and arrest people without mandate — thousands of young activists gathered at Paul Sauvé Arena, in the Rosemont neighbourhood of Montreal, in a show of support for the FLQ. As a direct consequence, 495 people were arrested. (To this day, many of them are still asking for an apology from the federal government.)

WATCH | Troops roam Quebec streets during October Crisis:

Signs of that polarization were already visible in 1965. During Schirm's trial, Régis Fortin’s family received death threats. For a time, a police detail kept a 24-hour watch over the family's home. Daniel was sent to live with his grandmother for a while.

François Schirm's name would haunt the Fortin family. As the events of the October Crisis unfolded, Daniel recalls his dad being drunk and "crying like hell" as he lay in bed. "I remember hearing my dad talking to my mom about, 'Oh, God, I hope they're not gonna come [for] me.'"

That feeling was heightened on July 24, 1978, when the family learnt of Schirm's release after 14 years behind bars. Daniel Fortin said his father was scared there would be repercussions for him.

- LISTEN | Learn more about the October Crisis on the CBC podcast Recall: How to Start a Revolution

IV.

At the height of the FLQ's notoriety, Sylvie Schirm was largely ignorant of her father's involvement. She was five at the time of the robbery at International Firearms, at which point her mother cut ties with her father, and later remarried.

It wasn't until 1973, when she was 15, that Sylvie first learned of her father's identity and political leanings. "I remember going into my mother's night-table drawer looking for a pair of scissors, and the drawer dropped and under the drawer there were articles from the newspaper about my dad."

Following his release from prison in 1978, François Schirm wrote two books, including an autobiography called Personne ne voudra savoir ton nom, which he dedicated to his daughter. (The English translation of the book title is "No one will want to know your name," a nod to a song about an FLQ activist arrested for planting a bomb near a monument representing a British conqueror.)

"I want you to know I love you, and I want to get to know you."

Several years later, Sylvie decided to contact her father. It was 1982, and at the time, she was working for an engineering firm in Argentina. Through a company secretary based in Montreal, Sylvie managed to get more information on her dad — and sent him a letter.

One day at work a little while later, the phone rang. It was the Montreal colleague. By the tone of her voice, Sylvie sensed something strange was happening. "She said, 'There's somebody who wants to talk to you.'"

The colleague handed the phone over to François Schirm. He identified himself and said that he thought of Sylvie every Nov. 13, her birthday. Sylvie said he told her, "I want you to know I love you, and I want to get to know you."

Sylvie Schirm was 25 by then. On a whim, she decided to pack her things and move to Montreal to reconnect with her father.

V.

During the '80s, Schirm made a few public appearances in support of the rights of fellow FLQ detainees. In 1987, he took part in a documentary where he shared his views on revolutionaries.

In looking at history, Schirm said, "there are only victors and vanquished. When you are vanquished, you are a terrorist; when you are victor, you are a patriot." Despite failing in his mission, Schirm clearly saw himself as a patriot.

Sylvie Schirm said her father never expressed remorse for the 1964 robbery that resulted in the deaths of Leslie McWilliams and Alfred Pinisch.

"I think he regretted that they didn't do [the job] well," she said. "I think he was conscious of what the consequences were of that incident, and he did 14 years in prison for that. But I never heard him saying that he regretted it, that it was wrong."

Schirm died on Aug. 3, 2014.

To Régis Fortin, who had been traumatized by the events of August 1964, it was a relief. But in some nationalist circles, Schirm was vindicated. In 2014, he was posthumously awarded les Grandes Palmes d’or patriotiques by the Rassemblement pour un pays souverain, an organization promoting the French language and independence in Quebec. Sylvie Schirm accepted the award on his behalf.

To this day, Daniel Fortin is puzzled that a number of respected artists and intellectuals — including stand-up comedian Yvon Deschamps and sculptor Armand Vaillancourt — supported Schirm following his release from prison.

"My dad was a huge fan of Yvon Deschamps and Armand Vaillancourt," said Daniel Fortin. "He got so mad when he learnt this. He was [like], 'Come on, guys, this guy just killed two people.'"

Régis Fortin died in 2016, after years of dealing with alcoholism. He did not receive the same type of recognition as François Schirm.

Sylvie said that when she reconnected with her dad, he shared his passion for politics and his adopted province. She called it "an enormous amount of learning."

"It was learning who my dad was, it was learning how to have a father and it was learning what Quebec is and what being a Quebecer meant," said Sylvie, whose family on her mother's side identified with the anglophone part of Montreal.

Sylvie believes that for all the violence, a lot of good came out of the FLQ era.

"When you look back, it was a totally different Quebec than what we have today," she said. "And I think part of that is thanks to my dad and everybody who was pushing a very extreme idea, which permitted the existence of the Parti Québécois."

Founded in 1968 after a merger with the RIN, the Parti Québécois arose as a moderate solution to the province's political issues. Following its rise to power in 1976, the party of René Lévesque established Bill 101, defining French as the language of the province. The party also held two referendums, in 1980 and 1995, and the latter almost succeeded in making Quebec an independent nation (failing by fewer than 55,000 votes).

"I don't think there's room for any more revolutionary movement," said Sylvie Schirm. "But on the other hand, maybe that's what we needed at the time… thank God we don't have that anymore."

Daniel Fortin, whose father was forever changed by Schirm's revolutionary actions more than half a century ago, is less indulgent about that chapter in history.

"The FLQ used the separatist movement to do what they did. The separatist movement — they were not killers, they were a pacifist movement trying to get something better," Fortin said. "The FLQ took that movement to a whole different level."

With files from Jessica Linzey and Geoff Turner

About the author

Francis Plourde is a journalist and producer for Radio-Canada in British Columbia. He co-produced the podcast Recall: How to Start a Revolution. His work has appeared on investigative programs such as Radio-Canada's Enquête and CBC's The Fifth Estate and in 2017, he was part of the team that reported on the Paradise Papers.