September 8, 2018

It's a story that in many ways echoes the one that inspired Come From Away.

A group of ordinary Canadians rose up to assist their grief-stricken neighbours when disaster landed at their door.

But no hit musical was written about the Flagship Erie crash that killed 17 passengers and three crew members of an American Airlines flight on the night of Oct. 30, 1941.

The plane came to its fiery end in an oat field in the small hamlet of Lawrence Station, about 25 kilometres west of St. Thomas, Ont.

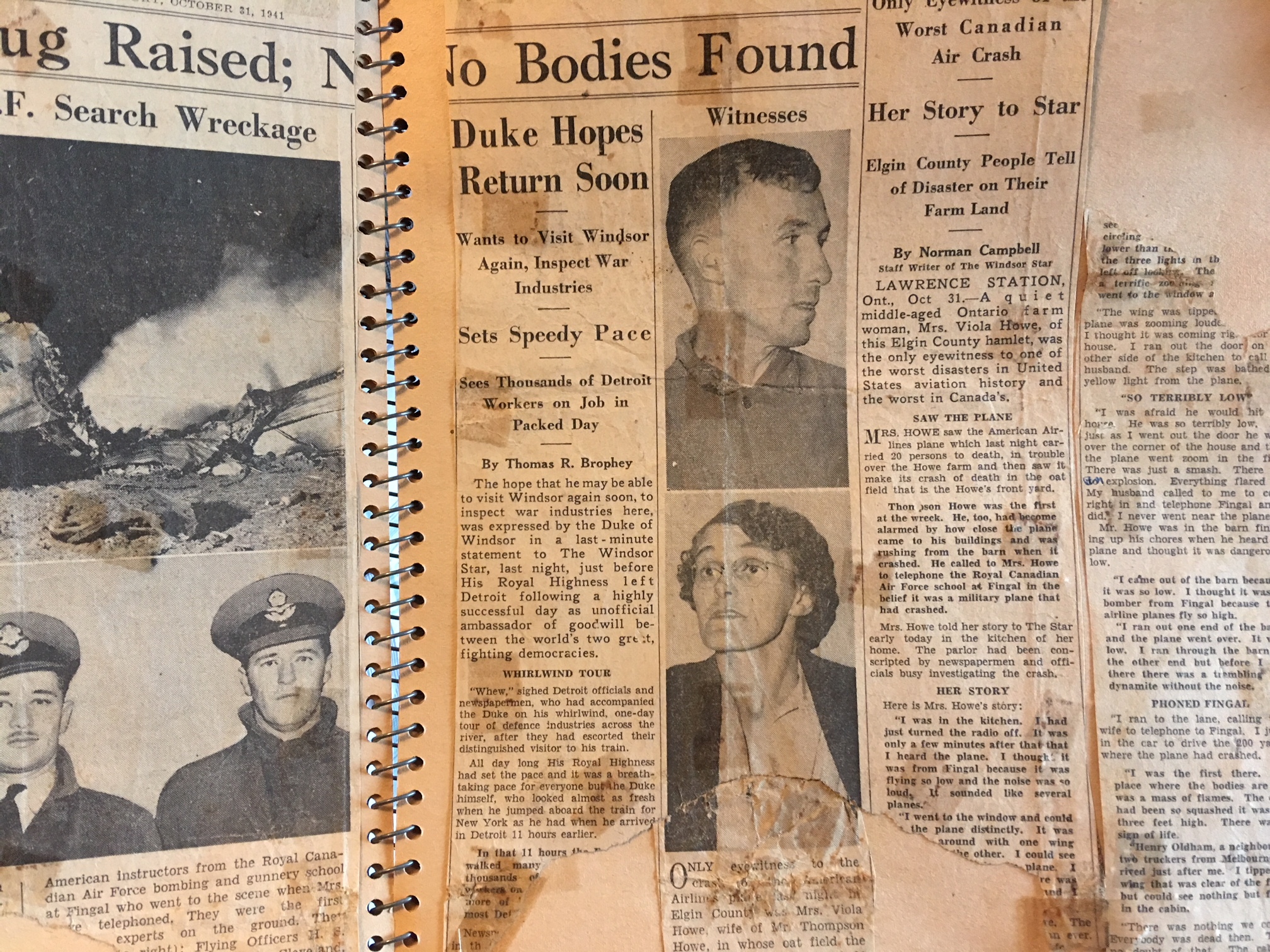

The story of the crash made the front pages of newspapers across North America. But with Canada enveloped in the Second World War and the Pearl Harbour attack to come only weeks later, Canada's worst airline disaster up to that point would quickly fade from memory.

That could change Sunday when a few hundred people will gather at the crash site to unveil a plaque that commemorates those who perished when the DC-3 went down.

For 82-year-old Ken Howe, Sunday's ceremony is long overdue.

On the night of the crash, he was a five-year-old curled up asleep in his family's farmhouse and dreaming perhaps of the Halloween party he planned to attend the next day. His brother Keith and sister Mary were also sleeping when his mother Viola Howe, staying up to sew their Halloween costumes, heard the roar of the plane's engines and looked to the sky.

It was about 10 p.m. and the plane had left Buffalo, N.Y., less that an hour earlier to make the second jump of a four-leg trip from New York to Chicago. The DC-3 was scheduled to land in Detroit that evening.

When Viola Howe looked up to the sound of roaring engines, she saw the plane loop around, pitch sideways at a sharp angle and fly past her family's house, nearly clipping its roof, before crashing about 200 metres away.

She stayed calm and called for help from the RCAF station down the road in Fingal. Airmen and firefighters arrived quickly and did what they could but the force of the crash and the spilled fuel combined to create a wall of heat and flame that made any rescue attempt impossible.

Ken's father Thompson Howe was working in the barn and would later tell his son about the crash.

"He said it shook the ground in the barn," said Howe, who now lives in nearby Shedden. The morning after the crash, his father drove Ken to school. The sight of the scorched plane is forever seared into his memory.

"It was very tragic to drive by that and see the plane still smouldering in the field," he said. "It took years off my dad's life."

Viola Howe kept an extensive clippings file of the newspaper coverage, which her son still has. The stories chronicle the family's attempt to do what they could in the moments after the horrible crash and in the dark days that followed.

The day after the crash, dozens of people arrived at the farm. Howe recalls going downstairs to find the house full of uniformed men.

Police, firefighters, airline executives, crash investigators and reporters were all being served breakfast by his mother, who kept the fire going against the damp chill outside after being up all night.

She also fielded long-distance calls from family members desperate for details and had to tell one victim's relative that no one on the plane had survived.

An Americans Airlines station manager for Windsor would later praise the Howe family for allowing their home to be transformed into a makeshift operations centre and doing what they could to help.

"The quality of people is often brought out in a tragedy," E.K. Glaves wrote in a notice published in a local newspaper. "I would like to express our gratitude to Mr. and Mrs. Howe. They have treated us 1,000 per cent right and we appreciate it very much."

The crash victims included a stewardess, businessmen and union leaders. Most left behind families with children.

The death of the pilot, Capt. David Cooper of Long Island, N.Y., meant his boys David Jr. and Peter — both younger than two at the time — would grow up never knowing their father.

Now 79, David Cooper Jr. will travel with his brother Peter and other family members to Lawrence Station for Sunday's unveiling.

Cooper Jr. holds a warm place in his heart for the Howe family and the many Canadians who live near the crash site and came to help, both then and now.

"We're enormously grateful to the Canadian people, both the people of that day 77 years ago and the Canadians of today," he said. "The people on that night, they didn't run away from tragedy and horror. They rushed toward it to see if anyone could be saved. Unfortunately, no one could be saved."

Cooper Jr. says the kindness of Canadians will not be forgotten by members of the victims' families. In previous trips to Ontario, he's stayed as a guest at Howe's house.

"This is just part of the affection that we have for the people of Canada when others are trying to drive a wedge between our peoples," he said. "This is just one more example of the closeness of neighbours."

David Cooper Jr., now 79, talks about the gratitude his family has for the Canadians who tried to help when the plane piloted by his father crashed on the Howe family's farm.

The crash and the investigations into its cause are well-chronicled in the book Final Descent: The Loss of the Flagship Erie written Robert Schweyer and published four years after his death in 2010.

His book describes a handful of exhaustive government inquiries that failed to reach a definitive conclusion about what caused the crash.

Everything from a bird strike to a mechanical problem with the auto pilot to a lightning flash was considered.

"The tragedy remains as much a mystery today as it did in 1941," Schweyer writes. "I am personally convinced that something either jammed or failed aboard the aircraft suddenly and without warning."

Two recommendations that came from the crash investigation would eventually lead to significant improvements in airline safety: The need for a device that could record what was happening on planes and a need to strengthen cockpit windows against possible bird strikes.

Raymond Lunn, 76, wasn't alive when the crash happened, but the lifelong resident of the area says he's elated there will finally be something to mark the site and the people who died there.

It will list the names of the 20 victims and include some text about the efforts the people of Lawrence Station and the surrounding communities made to help after the crash.

"It's my dream that we're getting this done finally," said Lunn. "It's a very sad thing. It was at the time and it still is in my books. To me it's out of this world to finally have this memorial."

Lunn sees a clear connection between the Lawrence Station crash and the events that inspired Come From Away, when Canadians opened their homes to airline travellers stranded in Newfoundland by the Sept. 11 attacks.

"We're Canadians and that's the Canadian way, I would say."