April 6, 2018

It’s a simple tattoo that reads: 04/07/2013. It reminds Jacob Wells of how easily he could have been one of "those guys" at a drunken party the night it all went wrong.

He really only knew Rehtaeh Parsons from the hallways of their high school in Cole Harbour, N.S., but now has the date of her death noted on the inside of his left wrist.

It marks the beginning of his awakening, one that forced him to examine some ugly truths about himself.

Because he knows he could have been one of the boys at the small Nov. 12, 2011, party where Rehtaeh said she was sexually assaulted.

The night the explicit photo was taken of the 15-year-old girl vomiting out a window as one of the boys had sex with her and gave a thumbs up, a picture that would be shared without mercy among Rehtaeh’s peers and lead to relentless bullying.

"I too could’ve caused something like that to happen," says Wells. "I too could have ruined a young girl’s life."

It's been five years since Rehtaeh Parsons was taken off life support following her attempt to take her own life.

Her death, the torment she faced when she was alive, and the justice, hospital and school systems that failed her, outraged a community and even a country, and compelled politicians and other officials to do something to prevent another tragedy.

The Nova Scotia government hastily drafted legislation to combat cyberbullying, a law struck down by a judge two years later as a "colossal failure."

The federal government took more time when it made the publication of intimate images without consent a crime, a law that has been used in at least one high-profile prosecution.

Watch CBC Nova Scotia's mini-documentary on Rehtaeh Parsons's legacy

One independent review of Rehtaeh’s case faulted police, the Crown and school officials, although it did conclude it was a reasonable decision not to lay sexual assault charges, in part due to inconsistencies between statements the girl gave to police.

Another review found her high school didn't document the cyberbullying. Yet another led to changes at the IWK Health Centre, Halifax’s children’s hospital, after Rehtaeh’s father, Glen Canning, said his daughter had been strip searched by two male workers during a psychiatric admission four months after the alleged rape.

After deciding against charges when Rehtaeh was alive, authorities reversed course following her death. Two of the boys from that night eventually pleaded guilty to child pornography-related offences.

It’s been five years of pain and reflection, but for some of Rehtaeh’s family, friends and others, the story today isn’t the photo at all. It is about sexual consent.

Last December, Jacob Wells shared the story of his own personal reckoning at an event to mark the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women in Chatham, Ont.

Rehtaeh’s mother, Leah Parsons, had helped connect him with a group there that was seeking a speaker.

Wells is now 25, lives in Lawrencetown, N.S., and works as a carpenter. But he still remembers with deep regret his high school days when he would drink, party and "get laid." Consent? Never discussed. Having sex with girls who didn’t say yes? Definitely.

He was several years older than Rehtaeh, but she was friends with his sister Amanda. After her death, the two began to talk about sexual violence. It changed his life.

These days, he writes in a journal about his reformed views on consent as a way to deal with depression.

But while he can talk to strangers about the experience, he admits he needs to grow a “backbone" when it comes to his own buddies at construction sites where he works. He can’t quite yet broach the uncomfortable topic of sexual violence.

"Nobody wants to talk about something like that," he says. "It’s the dead silence."

Instead, he listens to them talk about sports and catcall women.

That kind of uncomfortable talk is exactly what has brought 13 teenage girls together on a darkened stage in a drama classroom at Sackville High School in Lower Sackville, N.S. Their empowerment club is called Girl on Fire.

They’re brainstorming ideas for a play they’re producing for their classmates. The real-life drama stirred up by sexual assault and victim-blaming provides plenty of material.

"If you don’t hear a yes, then that means no," says Dawnavan Young, a 17-year-old.

A girl sitting next to her nods in agreement. "If someone touches you and you’re uncomfortable with that you’re not overreacting," says Mandy Geizer, who’s also 17.

The discussion is fitting for this group, which was born out of Rehtaeh’s tragedy. She was also 17 when she died, and these girls are examining the same heavy issues of consent, self-esteem and suicidal thoughts that dogged her.

Some of them were only 10 when Rehtaeh’s death made national headlines. They have, in this club, a sisterhood.

"If something like that were to happen, we’d all have each other’s backs," says Deana Symes, 16.

Girl on Fire was created by former teacher Jenny Kierstead after she was "devastated" by the death. The program, she says in the manual’s dedication, is Rehtaeh’s "life’s legacy."

More than 130 women have trained to lead similar groups in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Northwest Territories.

The Sackville High group was funded by a $3,500 grant from the Nova Scotia government so teacher Meaghan LeMoine could leave her classroom and lead the girls.

She, herself, is a rape survivor.

"I have, you know, had enough experiences in my life that I know, for me, talking about it does take the power away and it does help me," she says. "I just feel so honoured to be at this place in my life and in history and really feel like we’re doing something."

Madison Sasco was 10 and in Grade 5 when her mother had to explain to her the tragedy that was dominating the news.

She remembers being "baffled" about how such awful abuse could be inflicted, and amazed at how Rehtaeh "stayed brave for so long."

Sasco is now the same age Rehtaeh was when she went to the party that destroyed her life.

"We should just honour her by spreading her story and like, not, you know, just hiding it away, because it’s something really important," she says.

Girl on Fire is a club Rehtaeh never had.

In fact, she kept her own personal hell a secret from one of her best friends.

Bryony Jollimore remembers the day her best friend suddenly switched schools and changed her phone number without passing along a new one.

It made no sense. They had immediately clicked as Grade 10 students after Rehtaeh had arrived in February 2012 to Jollimore's school, Prince Andrew High in Dartmouth, N.S.

What Jollimore didn’t know at the time was that Rehtaeh was being humiliated by cyberbullies who were sharing over and over again the explicit photo, taken little more than two months earlier. Rehtaeh had already fled Cole Harbour High and Dartmouth High.

But her tormentors had found her again. So she was on the move once again, this time to Citadel High School in Halifax, then back to Prince Andrew in February 2013. All told, she switched schools four times in a year and half.

Jollimore believes Rehtaeh wanted so desperately to feel "normal" that she kept her pain hidden from even her best friend. The last time they talked they said they loved each other.

It was two hours before Rehtaeh tried to kill herself.

Jollimore dropped out of school for a few months to grieve, but also to get away from bullies who had turned on her after Rehtaeh’s death.

She isn’t sure why they targeted her, but one showed up at Prince Andrew High and threatened her if she didn’t stop talking about Rehtaeh.

Jollimore refuses to stop saying her name.

She’s now 22, a new mother, and has given her daughter the middle name Rehtaeh.

It’s Jollimore’s tribute to her best friend, who showed compassion and kindness, and loved animals and art — traits she hopes her child will possess.

She plans to share her friend’s story, even its sadness, with her daughter.

But she must also fend off criticism from people who tell her they can’t understand why she would name her child after, as Jollimore says they term it, "some girl that killed herself."

Her answer is simple.

"A girl who changed all the rules, changed how we view things," says Jollimore, who wants to become a youth mental health worker. Rehtaeh, she says, "almost rewrote what we think about mental health and suicide awareness."

David Fraser is the Halifax lawyer who helped bring down the anti-cyberbullying law inspired by Rehtaeh.

But even he says the whole debate over the explicit photo of the teen, freedom of expression and online trolls misses the real point of her story.

"Consent, young people, alcohol consumption, intoxication — all these other sorts of things that really was at the core of the beginning of what happened," he says.

Fraser fought the law that Nova Scotia enacted in August 2013, four months after Rehtaeh died. He argued it was a “dumpster fire,” a piece of legislation so far-reaching it allowed provincial authorities to seek court orders against those they deemed bullies for what amounted to online arguments.

In December 2015, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge agreed and struck down the law immediately.

Fraser has anxiously awaited its replacement, the Intimate Images and Cyber-Protection Act, which passed in the Nova Scotia Legislature last fall but is still not enacted. The intention is to allow victims recourse in civil court where the threshold of proof is lower than under federal criminal legislation.

The lawyer is also a critic of the new legislation, but for very different reasons. The Intimate Images and Cyber-Protection Act, he says, has swung too far by creating a heavy burden for victims that requires them to hire a lawyer and start a time-consuming lawsuit in order to stop cyber-harassment.

He hopes the concerns he’s raised with the justice minister will be considered as regulations to accompany the law are crafted.

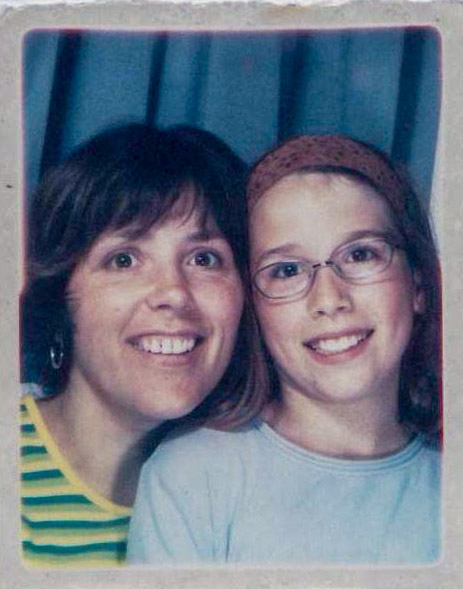

Every anniversary of Rehtaeh's death has been marked by a memorial walk through the streets of Cole Harbour, an event organized by her mother, Leah Parsons.

This year, for the first time, it will not go ahead. Parsons says it’s just too hard for her.

Since her daughter’s death, Parsons has become a reluctant public speaker. She’s given about 60 talks around the country to schoolchildren, police officers, lawyers and judges, and at trauma and resiliency conferences.

She shares a message about sexualized violence and the impact cyber abuse had on Rehtaeh’s mental health. But it reopens wounds.

"It’s been very healing in many ways, but I know now what the limit is, and so I think I’ve figured all that out," says Parsons. "It’s been a long journey."

Two months ago, she addressed a group of community college nursing graduates in Dartmouth, N.S. They were Rehtaeh’s age, and some of them knew her.

Rehtaeh could’ve been one of them. She would be 22 if she was still alive.

The emotional toll of "hitting the five-year mark is really difficult," Parsons says.

This year, she intends to head outdoors into nature to grieve.

But she’ll also think about the positive legacy Rehtaeh has left. There’s been a shift in conversation to speak out — and openly — about sexualized violence, and to show one another respect and compassion, she says.

And as it turns out, Bryony Jollimore isn’t the only mom who’s decided to name her daughter Rehtaeh. Parsons has heard of four parents who’ve honoured their daughters in that way.

"Every time her name is mentioned, her story is told — that keeps her alive in so many ways."

This new generation of Rehtaehs will grow up in a world where the conversation about consent has come alive, in part, because of a girl who helped to spark change and died struggling to be heard.