November 9, 2020

One man was watching TV at a Calgary homeless shelter in February 2016 when the priest’s face flashed on the screen.

Another was lying in bed in British Columbia when he saw it on the news. Another man, in Manitoba, saw the face he couldn’t forget flash up on Facebook.

Others were reading the newspaper — in a living room in downtown Edmonton, at work in Saskatchewan.

One by one, the men recognized the Anglican priest from their past.

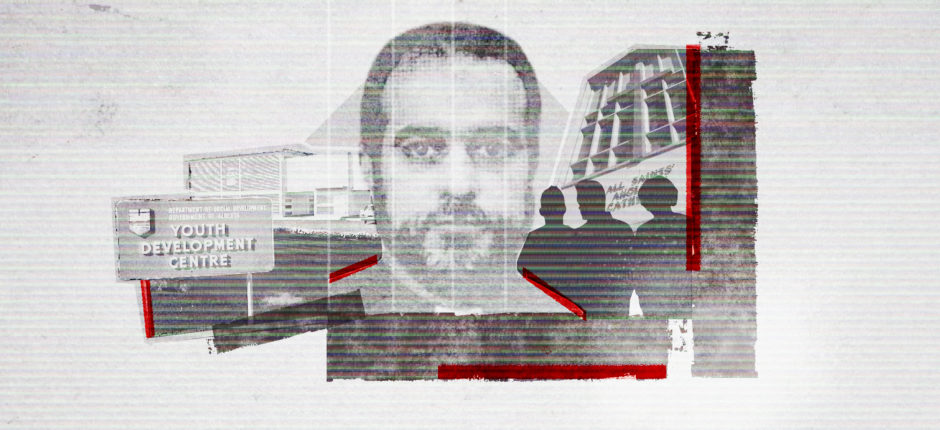

Rev. Gordon Dominey was set to go to trial on 33 charges related to alleged historical sexual offences against 13 teen inmates at the Edmonton Youth Development Centre.

Dominey worked at the since-demolished youth jail from December 1985 through July 1990.

Known to the teen inmates as Father Gord, it’s alleged he repeatedly sexually assaulted a number of boys.

“I’ve been ashamed my whole life.”

The complainants, by then middle-aged, opened up about the alleged assaults at a preliminary hearing held in provincial court in Edmonton to test the evidence against Dominey in 2017.

In the courtroom, the men found themselves facing Dominey. He wasn’t required to speak, but they were.

Crown prosecutors, and later Dominey’s defence lawyer, questioned the witnesses about events they’d spent decades trying to forget.

“It’s been an embarrassment to me my whole life,” one man told CBC News.

“I’ve been ashamed my whole life.”

After the preliminary hearing, a judge committed Dominey to trial. It was set for January 2020.

But the men never saw a verdict in the case. At a 2018 hearing, court heard Dominey was in the hospital with cancer.

He was 67 when he died on Nov. 7, 2019.

A year later, the men are taking another shot at justice by trying to bring a class-action lawsuit against the Alberta government and the Anglican Diocese of Edmonton.

In a statement of claim filed in 2017, they allege the diocese and the province are vicariously liable for Dominey’s actions.

They seek unspecified damages.

But in the years since launching their civil suit, progress has stalled.

Avnish Nanda, an Edmonton lawyer representing the men, says the church and province have gone to great lengths to delay proceedings.

To date, a judge has not certified the lawsuit as a class action.

Through an assistant, Edmonton Anglican Bishop Jane Alexander declined an interview because the case is before the court.

Alberta Justice Minister Kaycee Madu also declined an interview request.

“As this matter is before the courts, we cannot discuss anything related to the case,” Madu spokesperson Katherine Thompson wrote in an email.

“In addition, due to privacy legislation, we are not able to talk about anyone who may or may not have been a young offender now or in the past.”

Nanda’s clients are poor. They have faced challenges throughout their lives. Some remain incarcerated.

In recent interviews, three of the complainants said they want acknowledgement that they were victims.

They want the church and province to take accountability for what they say happened. They also want financial compensation for the suffering they believe derailed their lives.

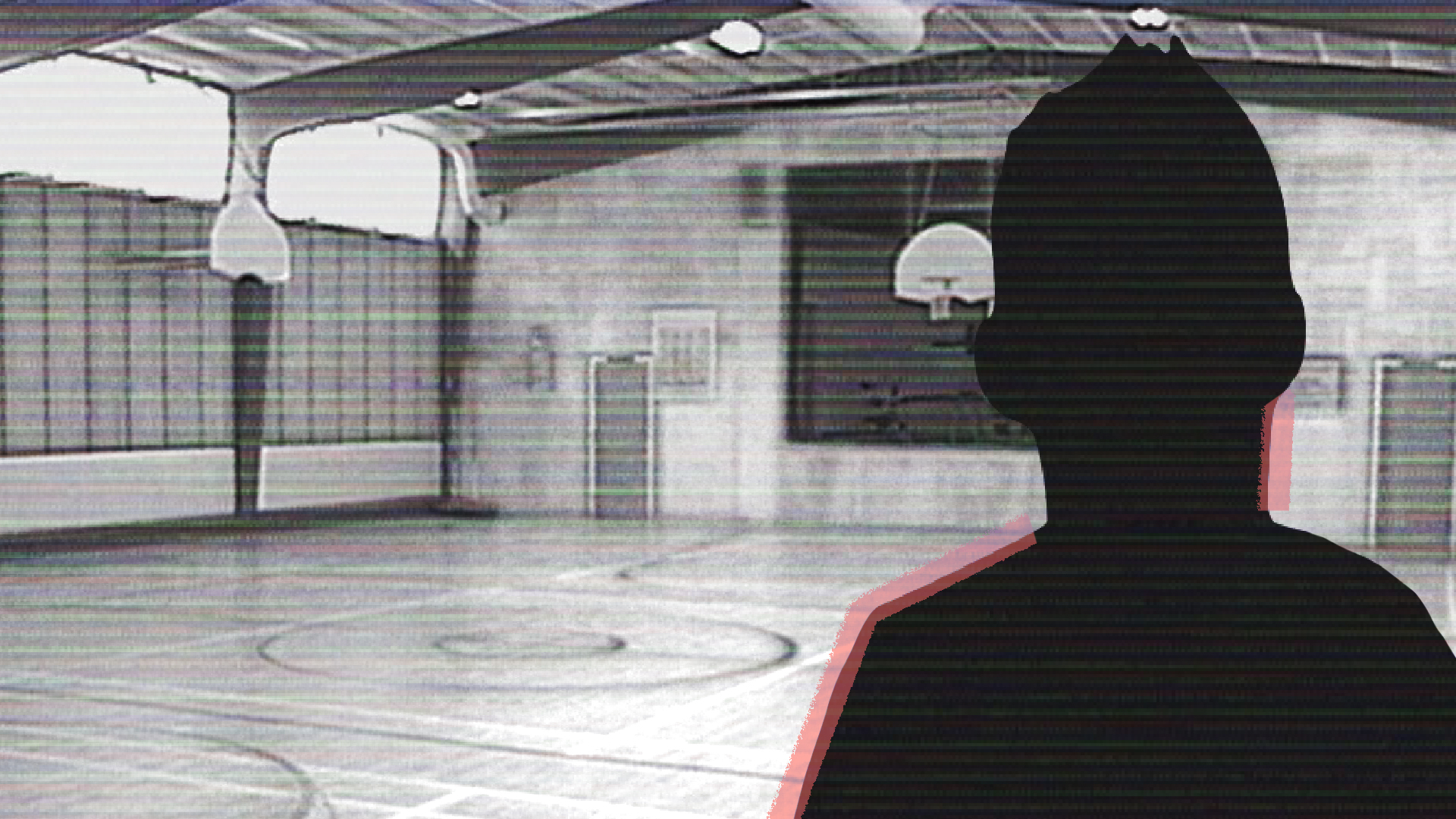

At the preliminary hearing, several men testified that while they were at the youth jail, Dominey would take small groups to the pool for evening swims.

Some said Dominey groped them in the water. Some said he sexually assaulted them in the locker room.

Others said assaults happened behind closed doors when Dominey met with them in one-on-one counselling sessions.

The preliminary hearing heard that Dominey was given access to private, sealed rooms where he met with boys.

Ronald Strauss, who was the facility’s assistant deputy director in 1985, testified that the priest would report back to him if he thought a boy was at risk of hurting himself.

“And then he would have free rein of the building in terms of the -- you know, running into the young people and spending time there,” Strauss testified.

A few of the men described one-on-one outings with Dominey.

One complainant said Dominey informed him he was taking him for a drive. The priest told him it was a spiritual journey. The man told court Dominey drove to a north Edmonton parking lot and assaulted him in the car.

Another man testified Dominey took him to a movie and then drove him to his own house, where he showed him pornography and assaulted him.

He said another staff member at the jail once asked him about the excursions with the priest, but he didn’t tell her. He said he didn’t think he’d be believed.

Others said similar things. Some of the men said they felt ashamed and embarrassed. Some said Dominey threatened repercussions if they tried to report what happened.

Some were silent until they talked to a police detective decades later.

One of the complainants couldn’t speak for himself. Instead, the transcript from the preliminary hearing shows that a recording was played in court.

On the recording, the 45-year-old described being abused by the priest.

Court heard the man killed himself 18 days after he was interviewed by police.

‘To hell with it’

Months before Dominey’s mug shot flashed on the evening news early in 2016, two inmates had decided to report him to police.

Longtime friends, the men had known each other for decades. Both had done stints in the Edmonton Youth Development Centre in the late 1980s.

They continued to cross paths later on when they were inmates in adult jails. The pair, and all of the other men alleging Dominey abused them, can't be named because of a court-ordered publication on their identities as complainants in a sexual assault case.

One of the men, now 49, said the pair took a while deciding if they should come forward.

“Because of the way of life that we’ve lived, it’s not OK to rat someone out ... it’s not OK to go to court and sit on a stand and point someone out,” he said.

“Finally we just said, ‘To hell with it.’ There’s got to be a turning point in life.”

"You could see the guilt on his face in the courtroom.”

And so they told detectives their stories.

Like others, the 49-year-old said Dominey targeted him following an evening swim.

He testified that the priest directed him into the locker room shower and used force as he assaulted him. Afterwards, Dominey threatened him with punishment if he told anyone, he said.

Like other men who testified at the preliminary hearing, he said he struggled with shame and trauma. The experience affected his ability to trust others and have healthy relationships, he said in an interview.

“I just became angrier and angrier, you know, and I use that to fuel everything I did.”

While talking about the alleged abuse is hard, he said he thinks it helps. He felt like Dominey had less power when he saw him at the preliminary hearing.

“He knew he was going to be convicted, you know. You could see the guilt on his face in the courtroom.”

He was at CDI College in Edmonton, beginning community service studies, when he got the news that Dominey had died.

It tore him apart.

“It was almost as bad as telling someone, and them not believing you, and just shrugging it off,” he said.

As his 50th birthday approaches, he believes he needs counselling to deal with his anger so he can pursue a career where he’s able to help others.

By his count, he spent 33 to 36 years of his life incarcerated. He said he never learned how to be a dad. He said he’d like to get treatment to help him repair his relationships with his children.

“I'd be a liar if I said that the money wouldn't help,” he said. “Of course it would. It would change a lot of things in my life.

“I'd be able to help my kids. I'd be able to build the things that I want to build, and do something good with my life.”

‘They’re all struggling’

Class actions are meant to facilitate access to justice: it’s cheaper and saves time for groups of people who have the same or similar claims to go to trial together, rather than one at a time.

Avnish Nanda, the Edmonton lawyer representing the men, said there’s also a social policy benefit in helping regular people hold larger institutions accountable.

“None of these individuals have financial means. They're all struggling and have been struggling since that period of time, since that incident and in many respects because of that incident,” Nanda said in a recent interview.

He said more men claim they were abused by Dominey than the 13 complainants in the criminal trial. He expects 15 to 20 men will form the class if the class-action proceeds.

But Nanda said the case is proving to be one of the most difficult he has ever had. He said the church and the provincial government are “pulling out all the stops” to delay the matter from moving forward.

“It’s disappointing. It puts marginalized folks, folks who have no money, in a very difficult position to hold people accountable for significant harms that they caused them.

“For my clients, some of them are losing hope.”

Priest transferred from Alberta to B.C.

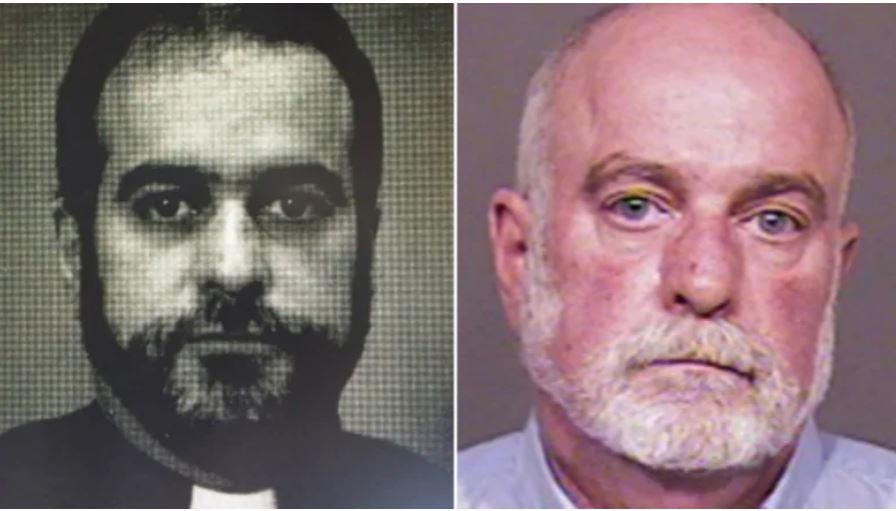

Dominey grew up in St. Catharines, Ont., according to an obituary published by the Anglican Diocese of New Westminster.

He became a priest in Ontario in the early 1980s, moving to Alberta to work for the Edmonton diocese.

In 1990, he was transferred to the New Westminster diocese in Vancouver. He worked in numerous churches.

According to the obituary, he also worked in a correctional facility in Chilliwack, B.C.

He was the priest in charge at St. Catherine's Anglican Church in North Vancouver from the summer of 2015 until his arrest in February 2016, when he was placed on administrative leave.

After the initial allegations were reported, the New Westminster diocese said there hadn’t been a single complaint about Dominey during his 26 years in B.C., and that his criminal record checks, completed every two years, had always come back clean.

At the time, one of his parishioners described Dominey as a lovely man.

"I'm very sad, very sad because I really liked him," the woman told CBC.

Dominey was survived by his husband, according to the obituary.

‘It changed the course of my life’

A cabin on a friend’s farm in central British Columbia has become a refuge for one of the complainants in the case. He got out of custody in March.

He said most mornings he wakes up and prays, and then watches the news. He’s unemployed, so he usually spends some time looking for odd jobs. Then he makes the nine-kilometre trip into town for methadone treatment for his heroin addiction.

“I just come back and watch TV. It’s a pretty boring life, which is OK with me, though. It was hectic for a lot of years. Chaos,” he said.

In and out of the Edmonton youth jail from age 13, he said he was 15 when Dominey assaulted him.

“It changed the course of my life. It turned me from a secure, confident pre-teen to a rebellious, no self-esteem, no self-worth child.”

He said he didn’t suspect that other boys had been abused as well.

“I didn’t at the time because nobody talked about it, right?”

He said he was able to hold it together while testifying at the preliminary inquiry. It felt good to finally talk about it. And it felt good knowing there were other people who understood what he’d been through.

“I don’t know if it’s weird but I felt comfort in knowing that I wasn’t the only one. I didn’t feel alone with it anymore,” he said.

“There’s power in numbers.”

‘Harder for other people to believe them’

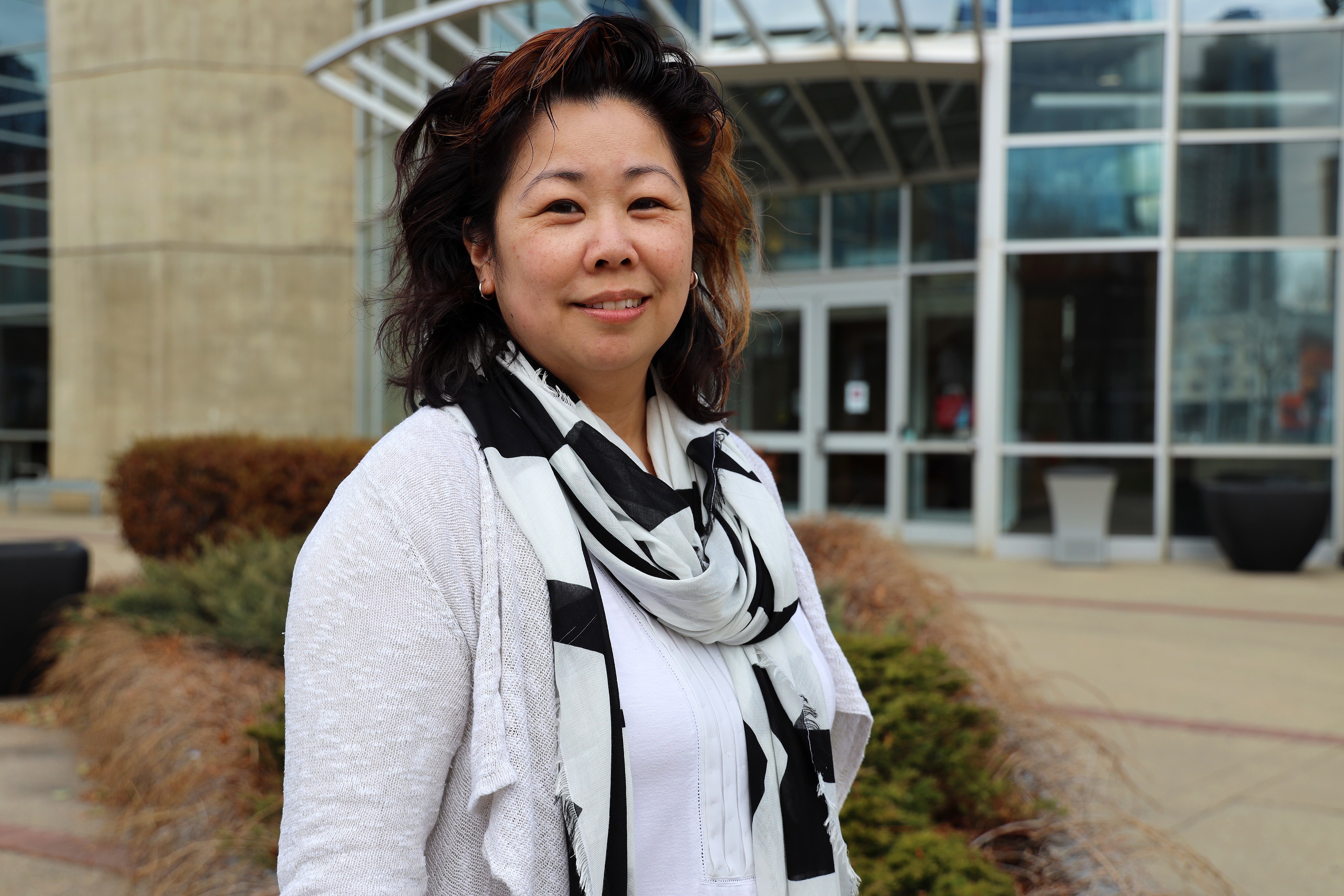

Victims who have also been offenders in the criminal justice system often face bias, said Prof. Sandy Jung, a forensic psychologist who teaches at MacEwan University in Edmonton.

“It’s harder for other people to believe them. There’s a stigma attached to them being an inmate, someone who is not trustworthy and lacking in credibility,” she said.

In a recent interview, Jung said that victims of sexual abuse of any age can experience consequences. Those consequences can be exacerbated for youth in their formative years.

“Typically what you’re going to find is that they’re going to have a hard time coping, so they start engaging in things that are really inappropriate, difficult and sometimes anti-social,” she said.

That can include drug and alcohol addictions, getting involved in a criminal lifestyle if they weren’t already and developing a distrust of adults.

For the men who allege Dominey abused them, their experience is even more complex.

Jung said that remaining in custody — in the environment where the abuse took place, either in the youth jail or moving on to other correctional institutions as adults — would be “awful” for dealing with flashbacks and nightmares.

And having an alleged abuser die before going to trial can pose an obstacle to closure, she said.

“In this particular situation, you don’t even have an offender who is going to deny it or minimize it, so for them to have to cope and struggle without having that person clearly give their account of it, and for you to be able to dispute it — there’s nothing to dispute.

“And I think that’s really unfair and unfortunate in this situation for them.”

‘A lot of guilt and shame’

In Kelowna, B.C., a man is haunted by thoughts that his life might have been different.

He had been in a bunch of trouble before he arrived at the youth jail in Edmonton in 1988, court heard during the preliminary hearing. In a recent interview, he said he was 16 or 17 when Dominey assaulted him three times.

He didn’t tell anyone. Instead, he tried to bury it.

The 50-year-old carried it with him as he tried to get on with life. He continued to be in and out of the criminal justice system but has stayed out since 2014. He worked in the oilpatch for a while. These days he works mostly as a house painter.

He’s uncomfortable dealing with people, even if they’re in his own family.

“You worry about how you act, and then I eventually had kids and I’m worrying about what they think about how I’m acting around them,” he said. “I’ve felt uncomfortable even being around them in certain situations. It’s just a lot of guilt and shame.”

Those feelings resurfaced when he saw a news report about Dominey being charged, but he decided he needed to tell his story anyway.

“I wanted to tell my side to make sure he never did this to anybody again.”

After speaking to police, he reached out to the Anglican Church in Edmonton. He wanted the church to take accountability for the kind of people they were hiring. He said he was told by the church to contact their lawyer.

But he reached out instead to Nanda, who looked into the case.

At the time, Alberta had a time limit on suing for sexual abuse: a suit had to be filed within two years of knowledge of the abuse. But Nanda wrote to Alexander, the bishop, anyway.

In a letter dated May 3, 2016, he outlined his client’s allegations and explained the trauma the man lives with.

“Justice for [my client] would include an apology from the Anglican Archdiocese of Edmonton, and financial restitution for the harms he has experienced and is continuing to work through,” Nanda wrote.

“Our aim is to not litigate this matter. Rather, it is to engage in meaningful dialogue between the parties so that [my client] can heal and move forward with his life.”

On Aug. 4, 2016, Nanda got a letter from lawyer Peter Gibson, representing the diocese.

“I note that at no point do you suggest that the diocese had any involvement in or knowledge of the events [your client] alleges,” Gibson wrote. “As you may appreciate, the proposition that the diocese should provide restitution with respect to events it has no knowledge of is decidedly problematic.”

Dominey was still alive at the time. Gibson said he should be presumed innocent of the assaults until proven otherwise.

He said that in the meantime, Nanda could reach out should any further information relating to the assaults arise, particularly any documentation.

But in May 2017, the provincial government changed the law about filing civil claims related to sexual abuse, eliminating the two-year time limit.

In September of that year, Nanda and his clients filed a statement of claim, seeking to have the group of Dominey’s alleged victims declared a class.

As the named plaintiff representing the group, the Kelowna man had to testify yet again, this time describing the abuses for the civil case in the Court of Queen's Bench in Edmonton.

Nanda said all his clients’ evidence has been submitted, but the province and church have continued to drag their feet.

At the latest hearing in September, Court of Queen’s Bench Justice John Henderson ordered Nanda’s clients to pay for a neutral, third-party lawyer to review all of Dominey’s records, Nanda said.

Nanda believes that’s unnecessary, and that, regardless, the church and province could have sought the information much earlier. The case will be back in front of Henderson on Nov. 10 to determine the next steps.

He said these types of administrative delays don’t happen in cases between commercial litigants, and that it’s unfair that survivors of sexual abuse have a different, more difficult path to justice.

“All the survivors have resolve, and they’re willing to move forward. But they’re of a certain age and they’re often of a certain health ... I’m concerned,” Nanda said.

‘It haunts me’

For the Alberta man who was one of the first complainants in the case, there’s nothing left to do but wait for justice to be served.

“I need this all to come to an end,” he said in a text message to a CBC reporter.

“I cannot continue to carry this because I have allowed it to consume me and consume my life.

“Those around me have suffered for it as well. I just don’t know how to get rid of the emotion that is attached to the pain. I feel it is unbearable at times, debilitating to say the least.

“I pray every day for some sort of escape from it, but it haunts me so I just want this to be over. Does that make sense? I hope so.”