June 13, 2018

Jerrie George has lost track of the number of homeless animals she has fostered over the past three years.

She's already caring for six cats, three chinchillas, three rats and a hamster in her tidy Mount Pearl home, but the latest additions don't take up too much room just yet — the four kittens are each tiny enough to fit in the palm of your hand.

They were found in a space under a large rock at a feral cat colony just outside St. John's.

Lyly Fortin has five more older kittens at home, all taken from the same site where Forget Me Not Animal Rescue had been running a trap, neuter and return (TNR) clinic over a week in late May.

The free-roaming feral cats are trapped and sterilized, and the adults too wild to be adopted are released back in the location where they were found.

"We always rescue the kittens. We never put kittens back ever, because there's hope with them," said Fortin, who co-founded Forget Me Not with friends Lisa Pike and Joan Simmons.

"When they get really hungry without a caretaker they start eating the kittens."

They started monitoring the property last year after a resident contacted them, concerned about seeing kittens that had been run over in the road. They investigated, and counted 27 adult cats living in the woods around a rural residential property.

It's just one of the countless cat colonies across the province that can spring from one abandoned animal or unfixed pet. In a couple of years, a single unspayed female that has kittens outside can turn into a colony of dozens of cats.

"There are so many cats here, I don't even know how we can deal with it ... and they live very hard lives," said Fortin.

"It's not unusual at all to have one missing a leg, one missing an eye, and they all have eye infections. When they get really hungry without a caretaker they start eating the kittens."

It's those images that keep Fortin awake at night, and keep the group busy. They rescue and find homes for stray and abandoned animals, respond to endless requests for advice and assistance, help look for lost pets, and hold TNR clinics whenever they can afford it.

The problem is human, not feline

This is the fifth TNR clinic they've done on the Avalon Peninsula since forming Forget Me Not in February 2017.

"Cat colonies are normally a human problem, not a cat problem," said Pike.

In six months, kittens born outside are old enough to start reproducing themselves, and one female can have three to four litters of six or seven kittens each year.

"Within a short period of time it can get totally out of control. You can't throw a nickel in Newfoundland and not find a cat. So everyone is trying their best to to help out the ones that they can."

The group has removed 48 kittens from that site alone in the past eight months.

Traps are set at various locations around the property, with trays of tuna placed inside.

A pungent kettle full of old moose meat from someone's freezer is boiled up on a propane stove set up on the hood of a car.

While municipalities in some other provinces contribute to the cost of TNR clinics, the group doesn't receive any financial assistance from any level of government.

"I have become a beggar," said Fortin.

"We sell everything in sight. We have auctions all the time, tickets on stuff, 50/50. We do a lot of education too. We are constantly raising money nonstop, and that alone is exhausting."

Running this TNR clinic is exhausting, too. Volunteers spend 12 hours a day at the site, most of it sitting in their cars all night, monitoring the traps.

The colony at this location has a caretaker — someone who regularly puts out food in a shed in their yard. The cats here aren’t starving, so the group’s menu has to be more enticing.

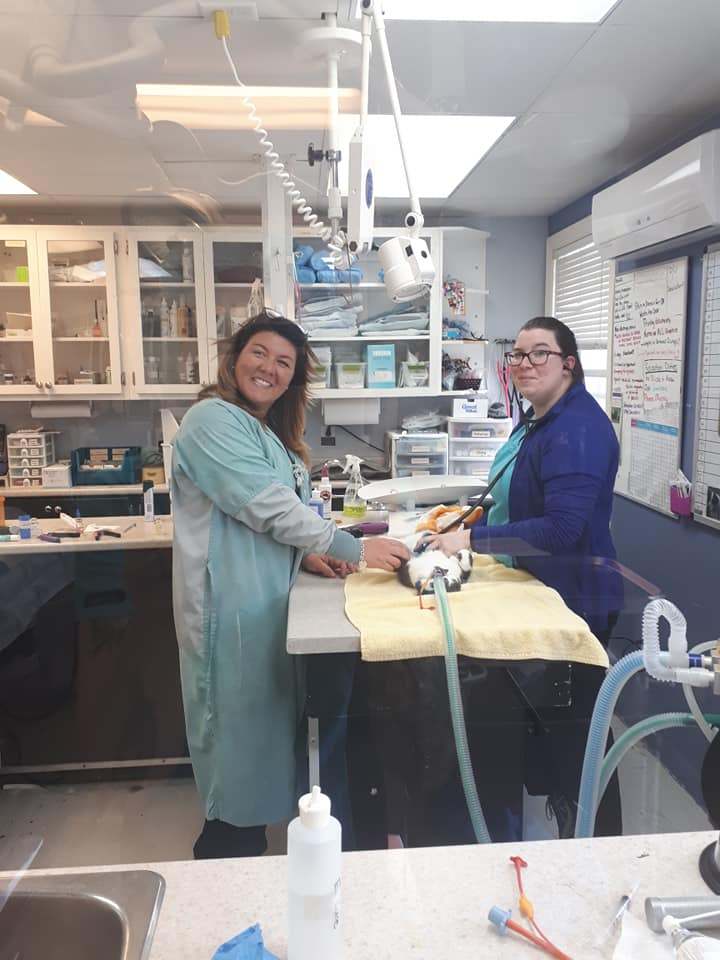

There's an added urgency because Avalon Animal Hospital in St. John's is donating the cost of spay and neutering of 25 cats, and that's a lot of tickets the group won't have to sell. Pike is using vacation time from work to make sure they trap as many animals as they can.

"It's just a passion. Helping little animals is probably the most rewarding thing that I've ever done in my life,” she said. “And even though I don't think that we're making a huge dent in the animal population in Newfoundland, the ones that we are helping, it does the soul good."

"There's nothing worse than seeing scared, starving, wet little kittens," added Simmons. "They're struggling, and some of them get sick, some of them get injured — it's just hard to see."

Despite the moose, and the tuna, and five long nights of waiting and watching, there are only eight carriers lined up on the property on release day.

"You can't throw a nickel in Newfoundland and not find a cat."

Watching the animals race back into the woods once the cage door opens is a moment of celebration for the group.

"It's fantastic. Their life is new, new, new. Now they can lie in the sun … no more babies … now they can retire," joked Fortin.

But the happiness is tinged with concern. Just hours before the release a neighbour approached them with some news — someone may be shooting the cats with a pellet gun.

"We need to find out more, but it's pretty clear that something happened. There should have been at least 50 cats here and there were only 11," said Fortin.

“Usually people poison them, but there's a lot of people that use them as target practice."

It's one of the reasons the group never reveals the location of the colonies they help.

While some people see feral cats as a nuisance or are concerned about threats to birds and other wildlife, advocates of TNR believe it is the best way to humanely control and eventually decrease the population.

“Rounding these animals up and euthanizing them year, after year, after year, is not making a lick of difference,” said Dr. Beth Marshall, a veterinarian and co-owner of Avalon Animal Hospital in St. John’s.

“It is a vicious circle: you trap, you kill, there’s more and potentially more even the following year. It's inhumane, it's horrible. It's a human-made problem and it's just not addressing the issue at its core,” she said.

Marshall said TNR causes the population to go into decline, whereas the animals not captured and killed continue to reproduce with less competition for resources, which can lead to even higher rates of reproduction.

“The reason the problem exists is because animals are not spayed and neutered, They are disowned by their owners, sometimes left in apartment buildings, thrown out on the street, abandoned,” she said.

“The heart of TNR revolves around spaying and neutering them so they can no longer reproduce and over time nature takes its course without replenishing the population,” said Marshall.

She has seen it work first-hand, taking care of a colony of cats that went from a population of 35 to three through TNR and continued care that includes providing food, shelter and monitoring for illness.

“So it really makes a difference long term.”

Forget Me Not is one of just a few other not-for-profit groups in the St. John’s area doing their best to tackle a huge problem, and it can be overwhelming.

"This is just people like you and me going crazy on their free time, and we're not making a dent," said Fortin.

"We need to lobby government. We need help from the top. We need a structure. We need much stronger laws and we need reinforcement,” she said.

“We need people who help us stop this, and we need people to spay and neuter their pets."

While they'll do their best to care for the cats that have been fixed and returned back to an uncertain future, the outlook for the colony's tiny rescues is much brighter.

The four kittens that were found under a rock have already been adopted, and will go to their new homes in a few weeks.