March 19, 2018

This time last year, he didn't care if that hit of fentanyl killed him. There were times when he would have welcomed death.

After several failed attempts at recovery and the break down of a relationship, the man whom we will call Andrew — the CBC has agreed to shield his identity — was suffering.

His journey into the world of opioids began in 2012, while home in Newfoundland and Labrador. Andrew was in a house with people who had the painkiller Percocet.

He didn't hesitate taking it. After all, he had been using cocaine and other drugs for years.

Three years later, Andrew stuck a needle into his vein and never went back.

"I stopped swallowing them. I stopped snorting them. And IV was the only way I wanted to use the drugs," Andrew said in an interview with CBC News at his St. John's-area home.

When he heard fentanyl had come to St. John's, and then about the subsequent wave of overdoses, Andrew wasn't worried about inadvertently taking the drug.

To the contrary, he sought it out.

"When I heard there was fentanyl available, I was like a kid at Christmas time," he said.

"I knew that now I could find something that was stronger that could basically get me where I wanted to be much quicker."

All the while, Andrew was working as a high-paid professional in his field, doubling secretly as a highly-skilled employee and drug addict.

On this day, he wears a cautious smile and is dressed in a neat plaid shirt and pants.

He's in his mid-30s, is well-educated, and breaks any stereotype people may have about the opioid crisis across Canada.

For years, he hid it well. Eventually, his lying and growing addiction became too much, and the things he held dear began to unravel.

The physical symptoms caught up to him. The withdrawals were too hard to conceal. The detox chased him.

"I lost very important roles in my career, and I was at a place where it was getting harder and harder to find work," he said.

Addiction wasn't new to him. It was an insidious disease that started young, and it meant concealing things with manipulation and lies — things Andrew admits he did well.

"When I had my first drink, something happened and I felt a sense of relief in my body," he said.

"I remember looking up to the sky and thanking whoever was up there for bringing alcohol into my life."

Andrew was 15.

Alcohol turned to cocaine. He went to university. The addiction worsened.

"Addiction doesn't do a background check when it comes knocking," he said.

"I have tried to outsmart it, outwit it but none of that has ever worked."

Suboxone is bridging the gap

Just when Andrew thought he was out of options, his doctor put him on Suboxone, a relatively new opioid-fighting drug that's been lauded across the country as the newest — and best — way to heal opioid addicts.

It's a combination of Buprenorphine and naloxone.

Suboxone blocks the opioid receptors in the brain, and produces less of a high than methdone.

It's also harder to overdose on — but not impossible, especially when mixed with alcohol or other drugs.

"Methadone has an effect where by you can have a buzz. It’s something that can make you very tired and drowsy," Andrew said.

"I’ve seen a lot of people continue to use on methadone, on drugs that can be cleared out of your system quickly."

Last year, seven people died in this province with methadone in their systems. Their deaths, however, may have been caused by a combination of methadone and another drug.

Dr. Bruce Hollett, divisional chief of family medicine, chronic pain and addiction at the Waterford Hospital in St. John's, is helping educate other doctors on how to prescribe Suboxone.

He recognizes some doctors may be apprehensive.

"The first fear was, is Suboxone Oxycontin? Is it just [that] we haven't been far enough down the road to see that this is an abusive drug?" Hollett said.

"My response to that is, that makes me afraid as well, after living through the Oxycontin scare, but we have 25-30 years of Suboxone being used world-wide and it hasn't reached that yet, it's always remained just as it is now."

It is Hollett's belief that Suboxone — paired with the right therapy — is effective.

"It’s the patient that's important," he said.

"We need to provide, perhaps, the safest of all opioids — Suboxone. We need to be able to put that in the hands of people where it will do good."

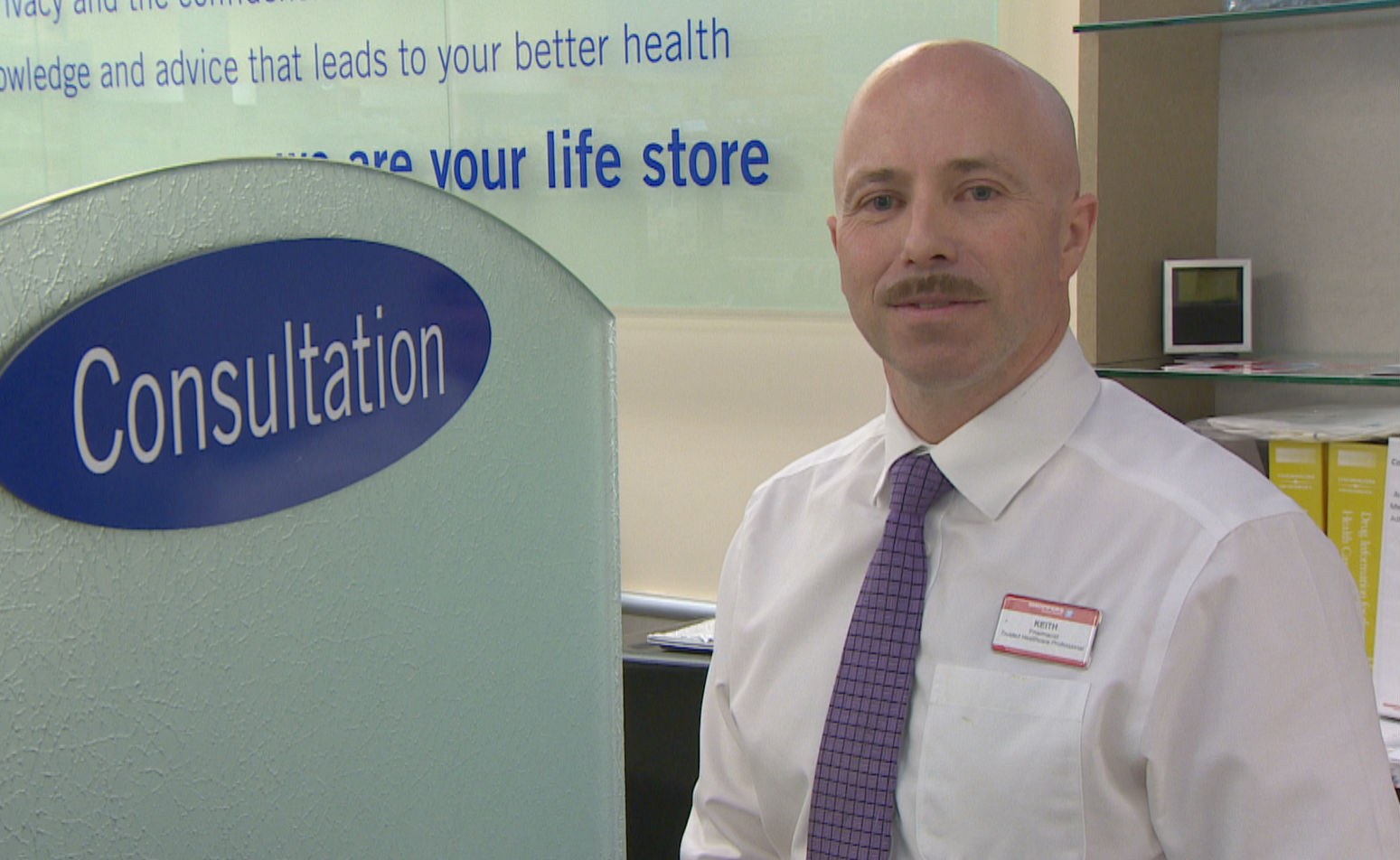

Pharmacist Keith Bailey treats some of those patients at Shoppers Drug Mart in Conception Bay South.

He estimates 15 per cent of his opioid-addicted patients are on Suboxone. The majority are on methadone.

"Suboxone is another feather in our arsenal," Bailey said.

He warns methadone shouldn't be dismissed all together, because it does work for some people.

And, he said, Suboxone isn't without its own set of challenges.

"It can be crushed and injected and when combined with alcohol and other drugs [it] can be very, very dangerous."

Methadone is a liquid that is diluted with a juice to be swallowed quickly. People on Suboxone could take as many as four tablets.

Pharmacists like Bailey have to wait until the pills are fully dissolved until the patient can leave.

"It is very much a crunch. Time is a real barrier. I'm in a private room with that person for 10 or 12 minutes."

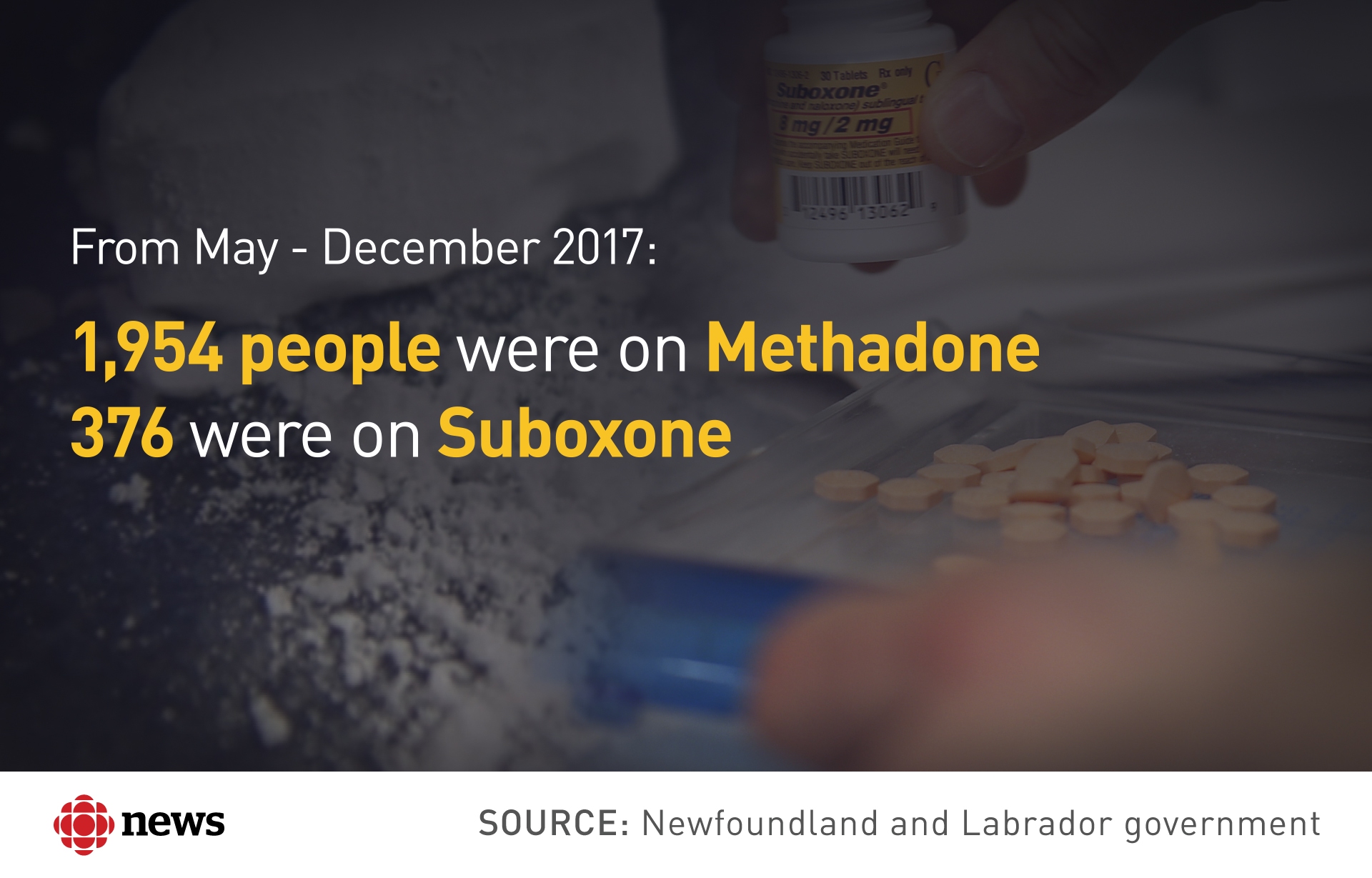

The province brought in Suboxone 18 months ago.

But there are far more doctors prescribing opioids than doctors prescribing treatment to get off those drugs.

Health Minister John Haggie said the shift will be gradual.

"I think methadone will always be part of the treatment process," he said.

"Experts tell me that there are a group of people for whom Suboxone simply won't work and methadone is the drug for them. But it's a second line treatment, not a first line treatment."

Andrew wants to help others with their addiction.

He hopes families of addicts can stick with their sick family member because it is a disease, he said.

His recovery is more than just Suboxone. He dedicates a minimum of two hours a day to getting better.

"I believe that if the province is going to invest in my recovery and spend a tremendous amount of money to help me recover, I believe that I have a tremendous responsibility to life up to that commitment," he said.

Suboxone has bridged a gap and allowed him to be free from the cravings that nearly killed him.

"It's not something I want to be on for life, but it's something that I've welcomed with gratitude, it's actually saved me likely from dying because using fentanyl, there was a very short distance from life and death," Andrew said.

"I want to continue down this path, I want to have a life worth living."