June 28, 2020

Even before the pandemic hit and upended life as we know it, Newfoundland and Labrador already had high rates of food insecurity, and there were already fears that things could get much worse in an rocky economy.

Groups that typically tried to shore up gaps for the vulnerable were left wondering if they could even continue to operate.

Things were conspiring against those groups in the early days of the pandemic. Distribution became a challenge. Some charities closed their doors as they went into emergency mode. The supply of cash dropped as the demand for food spiked. Fundraising became close to impossible, as people lost work, or prepared for worst-case scenarios.

The pool of volunteers who keep food banks and community groups running — many of them seniors — evaporated as many people went into self-isolation.

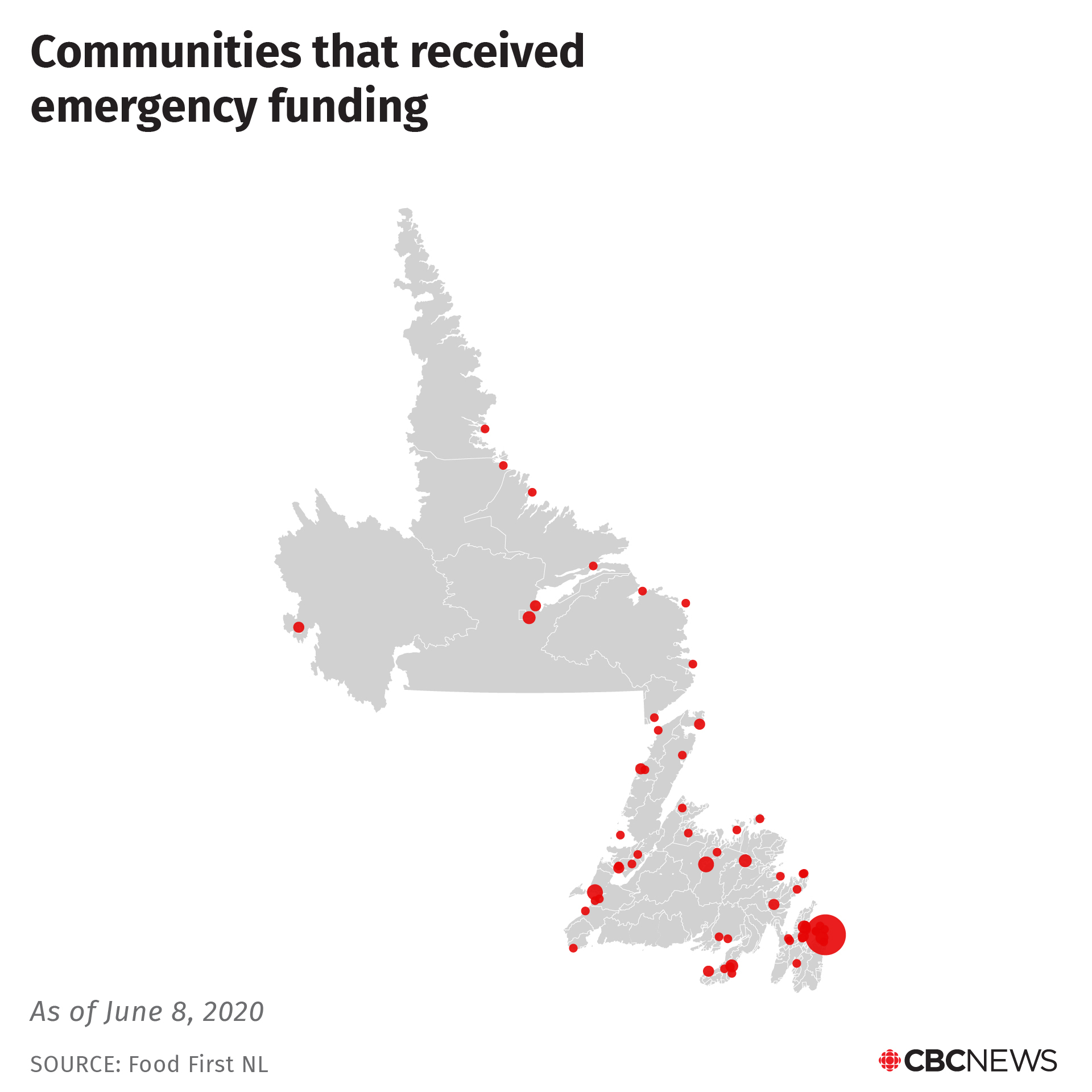

To deal with an unprecedented emergency, about half a million dollars in food funding was provided by the provincial government, to be distributed by the non-profit organization Food First NL.

Some 131 different groups have since received funding to help people who needed food.

The recipients are spread across the province (see the map below), and are quite diverse.

Indeed, this story is really a collection of stories, of the many different solutions and techniques that community groups have found to address specific needs on the ground, where they live.

Some groups have been in the business of helping people for years. Others had little to do with food assistance before the pandemic, but they saw a need and decided to do something.

Each group had to adapt and evolve in order to operate in a way that was safe and effective. Many of them also managed to find extra money for their efforts — through federal funding, for instance, or donations from local businesses.

We spoke to 11 of those groups.

Each one has a different pandemic story about what they did, and who they helped.

Finding pride and building community

Fogo Island Pride

Fogo Island Pride was still deciding on what events to hold in 2020 when the pandemic started to ramp up. Come April, the group realized COVID-19 wasn’t going away so it decided to pivot from Pride events toward community outreach.

Group co-founder and co-director Evan Parsons said the focus switched to food support for people who needed it. The group posted online and gave info to the local community TV channel. As the info got around and word spread, there was an influx of calls.

“We had a lot of people call us and inquire about the program,” said Parsons, adding the group thought they might receive 10 inquiries.

The number of individuals and families who needed food assistance quickly grew to about 35.

The calls were a mix of seniors, people with disabilities and people earning low incomes. All of them were vulnerable to an increase in food prices and saw COVID-19 make the act of getting groceries more of a challenge.

Parsons said the program provided eligible families with essential grocery items under Canada’s Food Guide at a value of $75 to $125 per month for up to four months. Since the start, local businesses have also donated money or assistance to the program. Looking at what they’ve achieved, Parsons said this kind of outreach also helps broaden knowledge of the LGBTQ+ community, which is one of the main goals for Fogo Island Pride.

If they can’t come in, go to where they are

The Gathering Place, St. John’s

Its name says everything about the raison d'être of the Gathering Place, a vital hub for people who live on the margins in downtown St. John's.

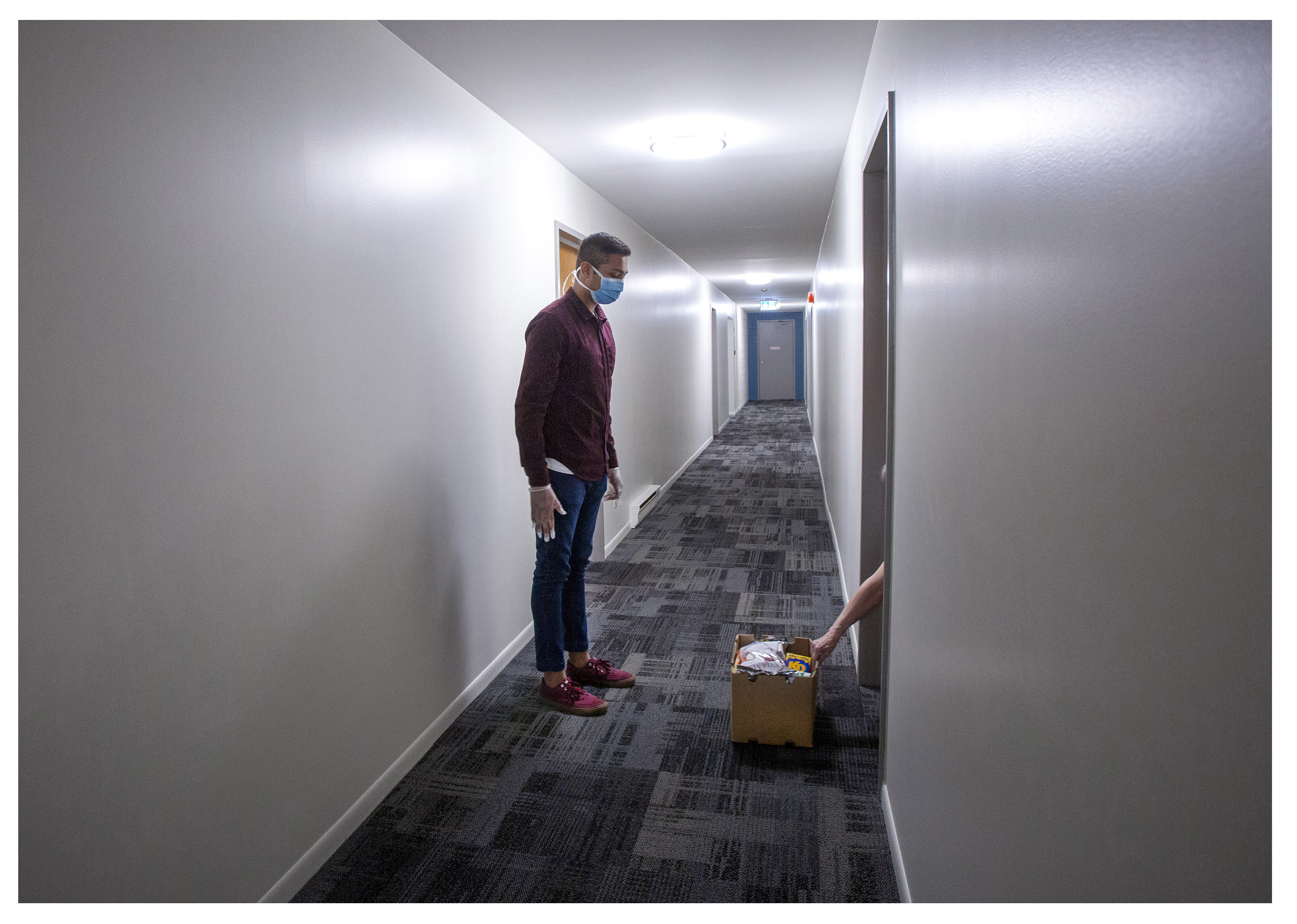

The pandemic, however, forced the Gathering Place to throw out its playbook and start over. If guests — the people who rely on its services are treated with respect, and that includes the noun by which they are known — could not come in for meals and life supports, the Gathering Place would go to them.

“Food insecurity hasn’t changed. What’s changed is how we ensure people receive basic food items,” said executive director Joanne Thompson.

In addition to producing takeaway meals, it also started delivering hampers. Thompson said the hampers are sent out with the needs and circumstances of each individual recipients in mind — the hundreds who frequent the Gathering Place tend to live in precarious housing and are some of the most vulnerable in the city.

“We understand some people don’t have abilities for refrigeration, some don’t have access to stoves and some don’t have the ability to even process that. What we pack in those boxes is really aligned with somebody’s lived housing needs,” she said.

The hampers are meant to supplement what people get from food banks and are set up for two-week cycles.

In addition to hampers and meals, the Gathering Place is also doing wellness checks on people — which means observing physical distancing guidelines and wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).

“We still have to find ways to meet people. To do it safely. It might require full PPE but that’s OK. We have to meet people where they are. We can’t ever think that we reach a point where we don’t engage with each other,” said Thompson.

What will the kids need?

Hopedale Inuit Community Government

Lift the lid of the community freezer in Hopedale and you’ll find a variety of frozen goods, mostly wild game and fish that has either been harvested by local hunters or donated by the Nunatsiavut Government.

There’s char, bison, moose, seal meat and turbot, to name a few.

The freezer was set up 10 years ago as a way to help provide traditional foods to vulnerable families in the community of about 650 people. Inside the community pantry, which goes hand in hand with the freezer, you’ll find the main staples: flour, sugar, salt and milk.

In a northern town where prices are high and incomes are low, foods that many of us take for granted can go a long way, especially if you’re a kid.

When acting town manager Donna Flowers saw an email from Food First NL about the emergency funding, she knew exactly what she’d use the money for.

But it wasn’t for the regular items. Not the milk, or flour, or char. She thought of the children in the community and about the foods they might be missing since the schools and their breakfast programs were shut down.

Flowers placed a bulk order from a grocery store in Happy Valley-Goose and stocked up on snacks like popcorn and nutrigrain bars. She also bought diapers and baby wipes for families — not food, but essential items all the same.

Before the pandemic started, the freezer and panty were open once every two weeks. The need has since increased, so now it’s once a week. Flowers thinks about 100 households are taking part, and she said that this help doesn’t go unnoticed. “They really appreciated that they were thought of in that way, making them feel like they are a part of the community and they are important.”

Putting dignity to the fore

Family Food Initiative, St. John’s

The Family Food Initiative is a brand new collaboration that came about in response to COVID-19 and serves students and their families in the east end of St. John’s. It was started by a group of women, including Krista Brodeur, who also helped start the St. John’s Baby Clothes Library.

During the pandemic, Brodeur recognized the elevated need for support for families who have relied on programs like the Breakfast Club and the local School Lunch Association. As a member of the congregation of St. Mark’s Anglican Church, and seeing the community work the church already does, Brodeur approached Rev. Robert Cooke to be a partner. He was only too happy to help.

A couple of schools in the area — East Point Elementary and Macdonald Drive Elementary — also came on board. Together, the group identified families in the area who could use some help.

“The thing that has struck me is the cross-section of the population. There's no stereotypical or socioeconomic status that this has affected — it's across the board,” said Brodeur.

With the funding from Food First NL, along with donations from the public and Colemans grocery stores, the group was able to support 60 families. Each week, these families were given grocery gift cards, so they could buy their own food. Cooke said that was an important element.

“With the gift card, you can go and you can pick up the things that you need rather than getting a hamper that might not specifically work for your family,” he said. “One of the things that was really, really important to us was to let people keep their dignity.”

Mental health is important, too

Flat Bay Band

On the west coast of Newfoundland, Flat Bay Band chief executive officer Liz LaSaga said food and mental health assistance were what people in her self-governed Indigenous community needed when the pandemic hit. That meant a lot of mental health services had to move into the virtual world.

She said the community has a variety of issues — people with compromised health due to chronic disease; vulnerable seniors; addictions and mental health challenges; homelessness — and all of them need support.

On food security, LaSaga said the band sent out a community memo offering help for people who needed it. Then they partnered with the local grocery store so that people could place orders.

“They call the store up and [place] an order into the store with what they need, whether it’s juice or eggs, or meat,” she said, adding the band has even helped out seniors with licences for salmon so they can have fresh fish.

So far, at least 178 families and individuals have received food help.

They used to be strangers. Now they play on the same team

School Lunch Association | Choices for Youth | St. John’s Farmers’ Market

This story is about an urgent need to solve a problem, and how a creative solution was found by making connections where they had not existed before. It involves the above three groups.

First, though, take a moment, and picture what feeding 6,300 people looks like.

That is, basically, like hosting a dinner party for a town the size of Clarenville.

It’s also the number of meals served to students in 36 schools across the province every day through the School Lunch Association.

Abrupt closures of the schools in March meant quick thinking on the part of John Finn, executive director of the School Lunch Association, not only about what to do with all of the food that had been pre-purchased for the full school year, but about who in the community could use it.

"None of us knew each other to begin with, but non-profits, they always find ways to work together."

— John Finn

When you think about all those daily meals, you can get a sense of just how much food needed to be redirected.

Finn’s first phone call was to a friend at Choices for Youth, a non-profit organization that provides support to vulnerable youth in the St. John’s area. He was soon in touch with Jen Crowe, the strategic initiatives coordinator with Choices for Youth. They came up with a plan to collect the food from the schools, find somewhere to store it, and then distribute it to the people who need it.

What better place to do that than the St. John’s Farmers’ Market?

Executive director Pam Anstey was only too happy to come on board to offer up the market’s 14,000 square feet of space. The move meant a shift in that organization's perspective.

“We’re the Farmers’ Market, so we do food but we don't do food distribution,” said Anstey.

“It was a really big kind of adjustment for us as well to try to wrap our head around how we could do this safely and in the most immediate way possible.”

Others pitched in. Businesses donated tractor trailers and moving trucks, and Royal Newfoundland Constabulary cadets helped transport the food.

This intentional yet impromptu grassroots project wound up providing food to 18 different groups, including shelters, residential centres and food banks.

New bonds were forged, too.

“None of us knew each other to begin with, but non-profits, they always find ways to work together,” said Finn.

‘We shouldn't have to make people climb ladders’

Safe Harbour Outreach Program

Many people who’ve found themselves out of work have options, like unemployment insurance or the federal Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). But what happens to those whose industry isn’t protected, or where there aren’t traditional employment benefits?

According to Heather Jarvis, program coordinator with SHOP, or the Safe Harbour Outreach Program, the pandemic has been especially devastating to sex workers. They’ve experienced a huge loss of income because of physical distancing guidelines and self-isolation measures, as well as a decrease in overall service.

In the six years of its existence, SHOP has assisted more than 550 people, a number that Jarvis said is climbing quickly. But their team is small, made up of only two full-time employees.

With an increased need for more support at the start of the pandemic, they had to act quickly. With the Food First NL grant money, SHOP hired a long-time volunteer as a temporary outreach worker. Her job: to deliver grocery gift cards to sex workers who find might find themselves struggling. A seemingly small gesture, but an example of meeting the needs of those who may already find themselves in challenging circumstances.

“COVID-19 has helped a lot of people understand the gravity of the inequality we're seeing in our communities and the immense power imbalances,” said Jarvis.

“I'm really hopeful that on the other side of this we will be seeing some big shifts in how we support people … and how quickly we can give people access to basic resources. We shouldn't have to make people climb ladders or tell us every personal detail about their lives to simply access a resource.”

Rallying around seniors

Saltwater Community Association

In Bonavista, Saltwater Community Association CEO Betty Fitzgerald said the pandemic caused a great deal of concern about one group in particular.

“We were worried about our seniors in general, especially those who are widowed or single seniors and we were wondering how we would go about helping them out,” said Fitzgerald, a former mayor who is a senior herself.

Fitzgerald said an increase in food prices meant it became harder for many seniors to afford the basics. The association got $5,400 in funding to start and used that to purchase 141 food hampers and 50 gift cards. Calls kept coming in from people who needed help, so the group kept looking for — and finding — funding, both locally and federally. They’ve since brought in another $20,000, and have expanded their help for anyone who needs it.

To date, they’ve given out 774 hampers in the Bonavista region. Fitzgerald said she’s also been contacted by some of the people they’ve helped.

“One lady called me and said it’s the first time anyone has given her anything. And it came at a time when she was wondering what she was going to have the next day for her meal,” Fitzgerald said.

A food bank that delivers

NL Eats

This is an organization that started as a family affair. When the pandemic hit, six people — all related and living in the same home — felt they needed to do something to help out.

So they started a food bank that delivers.

“We’re trying to cater to a bunch of different niches but at the core of the sentiment is seniors, elderly, immunocompromised … people with existing physical or financial conditions,” said Mahmudul Islam Shourov, the group’s chief marketing officer.

- Read more about NL Eats: Food bank in the bubble: How this family launched a service from their home

The group saw that a lot of people had no ability to get to and from a grocery store or food bank, because of cost, lack of transport or health issues.

They’ve been filling those gaps. Since the start of the pandemic, they’ve done more than 1,000 deliveries and have grown to 80 members strong and have plans to continue getting bigger.

The group has been in talks with Clarenville and Corner Brook where they are looking at setting up services.

Shourov said food is just the first step. “Food isn’t really the primary solution now. There’s so much more to it. There’s loneliness — there’s a lot more we need to address,” he said.

NL Eats is starting to offer mental health services as well, including counselling services and check-back calls.

'Because of this we won't be hungry this week'

Town of Roddickton-Bide Arm

Roddickton-Bide Arm, located on the eastern side of the Great Northern Peninsula, was once a thriving town where both the fishing and forest industries meant plenty of work for people in the area.

But its fate would be a dismal one: the sawmill closed first, followed by the crab plant. Many had no choice but to leave and find work elsewhere.

These days the town is much more quiet. For Mayor Sheila Fitzgerald, the pandemic highlighted just how difficult it is for some families.

“There's an increase in the number of people going away that are seasonal workers, there's lots of low income families, and it’s an aging town,” she told CBC.

To address the needs, the town hired a worker to deliver food hampers and items like prescription medications. She said seniors, especially those who live alone and are more severely impacted by isolation, especially welcomed a friendly face and the extra support.

In addition to the food hampers, the town used other grant money along with personal donations to open up a food pantry, housed in the local fire hall.

The word “pantry” was intentional, said Fitzgerald. “It’s warm and inviting and we want them to feel the hospitality, to come in the pantry and get whatever you need.”

It began by using Facebook to connect with people. They received confidential requests for food which they then could bring directly to people's homes. Fitzgerald said, “We hear everything from ‘you guys are angels’ to ‘you know, this means so much to me and my family. Because of this we won't be hungry this week.’”

An international pantry

Association for New Canadians

Refugees faced multiple barriers during the pandemic.

“People who arrive as government-assisted refugees experience a higher prevalence of food insecurity in the best of times when [they] resettle in high-income countries like Canada,” said Suzy Haghighi, director of settlement services with the Association for New Canadians.

Haghighi said it’s a process to settle and make a life in a different country, with a different culture, different language and different foods. Adding to that stress was the social isolation of the pandemic and the difficulties that came with it.

Haghighi said many couldn't access food banks because of difficulty navigating systems and language barriers. Plus, she said what’s available at food banks tends to be unrecognizable for newcomers and may not align with cultural or religious requirements.

So the Association for New Canadians purchased and started delivering culturally appropriate foods by starting a dry food pantry. They also purchased gift cards to help with fresh foods, diapers and over the counter medicine that was needed. They supported about 50 newcomer families in need.

Where do things go from here?

For the most part, these groups will continue what they’re doing through the summer months and wait for whatever comes next to happen.

On the horizon is a worry about a second wave of COVID-19 and questions about whether the need in their communities will further increase if the economy doesn’t bounce back.

The work on food insecurity that these groups have taken on has no doubt been critical in helping people through an unprecedented time. It’s similar to the triage process in an emergency room, where the most urgent cases are seen first. The process, though, doesn’t prevent the emergency from happening.

“The need is really incredibly high, even in the best of times,” said Josh Smee, chief executive officer of Food First NL.

“So this has helped meet some of the emergency dynamics of the situation but there’s still a systemic problem that we have.”

About Fed Up

Fed Up is a year-long series by CBC NL, in collaboration with Food First NL, exploring the issues surrounding food insecurity and why many people in the province struggle to access food.

Here are some of the previous digital stories we have done in this series:

Hundreds of MUN international students needed help for food during the pandemic. Some still do

Pandemic drives up demand for food support groups — with more challenges ahead

Food bank in the bubble: How this family launched a service from their home

Food banks are in for a rough ride, but $500K pledge from province is big help

When you can't afford to hoard, what happens then?

This tiny town's bulk buy program is fighting food insecurity

From statistic to survival: How one family deals with food insecurity

What did Snowmageddon teach us about food insecurity?

N.L.'s fall from grace on food insecurity record 'disturbing'

Single parents hit hard by food insecurity

Unseen hunger: How a community effort brought food to those who needed it most