November 4, 2018

This story is part of a CBC News investigative series that examines ATV and snowmobile deaths throughout Atlantic Canada, a region that by some estimates takes in more than $800 million a year from the industries related to these vehicles. Look for more coverage in the coming weeks.

June McCullough pushes two dragonfly lawn ornaments into the ground on the shoulder of a dirt road in Shanklin, a 42-minute drive east of Saint John, N.B.

The new dragonflies join the flowers and butterflies already adorning a wooden white cross in the community not far from the Bay of Fundy.

A stranger made the cross and placed it here to mark the spot where McCullough's 28-year-old daughter, Randa, died three years ago.

"I think next summer, I might have to come out and paint this," the mother said.

McCullough hung butterflies from the tree her daughter hit after catapulting off a four-wheeler.

Randa hit the tree and broke her neck.

The butterflies blew away over the winter. But three small angel statuettes guarding the makeshift memorial have survived.

"I'm so thankful that this is all here," McCullough said.

It's the first time the Saint John woman has visited the memorial this year. She plans to come back soon, but it's a hard trip to make.

Visiting her daughter's grave is one thing. But here? She pictures Randa lying in the spot where she took her final breath.

"This site makes me sad," she said, brushing tears away. "I'm going to try not to cry.

"Because I know that's where she laid. It was always in my mind. Did she call for me? I wasn't here to comfort her. I wasn't here to hold her."

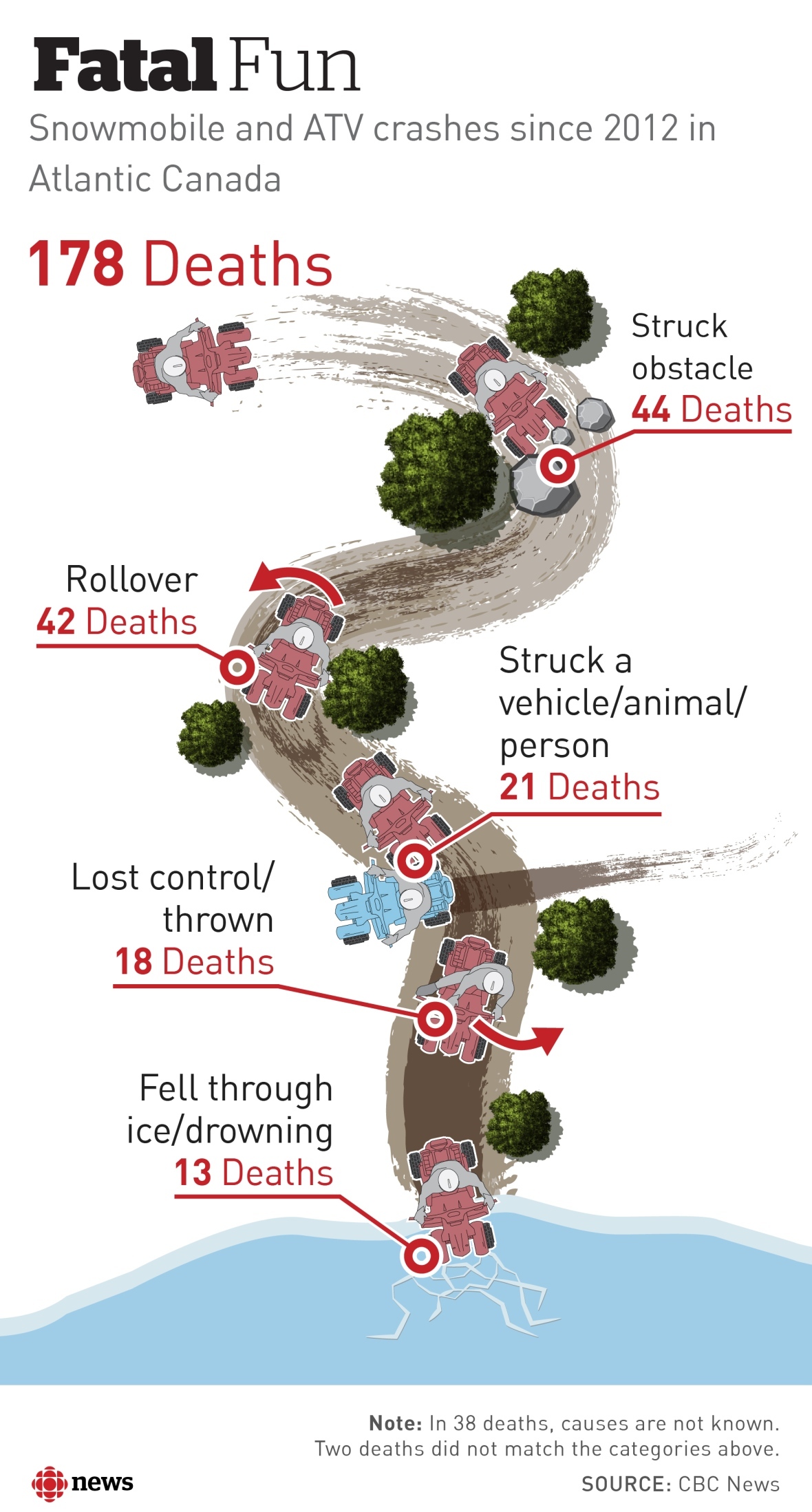

Randa is just one of more than 178 people in Atlantic Canada who've been killed on ATVs or snowmobiles since 2012, a CBC News investigation has found.

It's not clear how many people use these types of vehicles, but there are more than 360,000 of them registered in the four Atlantic provinces. Most riders use them recreationally.

CBC News analyzed the 178 deaths, collecting information from police, news clippings and obituaries and speaking with dozens of families.

It found that in most cases, victims were middle-aged men. About a quarter of the victims died in rollover crashes, and another quarter died the way Randa did: after crashing into a tree or other stationary object.

'Randa never made it'

Randa was good-natured and kind, McCullough said, the type of person who showed no animosity toward others, who loved family dinners and having girls' nights with her two young nieces.

She was proud of her job at a Sitel call centre in the city, often winning prizes for her performance. Once, she won a Sobeys gift card.

She didn’t have much in her own cupboards, but Randa heard of a family who had even less.

"She didn't know them people," her mother said.

"But she found the address out and went over and knocked at the door and gave them that food voucher. That's the type of person Randa was."

But it's her daughter's laughter that McCullough misses the most.

She's grateful that her final conversation with Randa ended with, "I love you."

On May 16, 2015, Randa and her sister, Clara, were part of a group that spent the day four-wheeling on the outskirts of Saint John. It was Randa's first day trip on an ATV.

One of their stops was the May Run, an annual event that mixes mud, machines and, for some, booze.

Randa was drinking that day, according to the coroner's report into her death. Chris LeBlanc, who took Randa as a passenger on his four-wheeler, said he was not drinking. Clara, too, said LeBlanc wasn't impaired.

After a stop at the May Run, the group went to a friend's camp. By the time they reached Town Plot Road in Shanklin, about 11 kilometres from the May Run, it was late afternoon and the sun was beating down into the riders' eyes.

As LeBlanc remembers it, he was between two other groups of riders, going 50 to 60 kilometres an hour. The machines were kicking up dust, and LeBlanc said he kept his distance from the group in front of him, trying to see through the cloud.

To this day, he isn't sure whether it was the sun or the dust that made him lose control.

"I'm not sure what happened at that point, but I came up over the knoll, and it was like a sharp turn and kind of a slope," LeBlanc said.

"That's pretty much all I remember."

He remembers rolling down into a ditch and up to the other side. His knee was turned sideways.

The pain was "excruciating" as he waited for an ambulance.

"Then I ended up finding out that Randa never made it," LeBlanc said.

"That made it even worse."

At the hospital, he found out he broke his back, suffered chest trauma and tore the ligaments in one leg. The injuries would keep him off work for almost a year.

He thinks about the crash nearly every day. He bought another four-wheeler, but he has never taken another passenger with him.

"I knew it was an accident. There was no alcohol or drugs involved, and I wasn't fooling around," he said.

"In the back of your mind, you're thinking, 'Oh God, this is their child.'"

Still, it's been hard. The only thing that has helped, he said, is a visit Randa's family paid him in the hospital. They told him they didn't blame him for what happened.

"In the back of your mind, you're thinking, 'Oh God, this is their child.'"

Randa, who was thrown from the machine, landed much farther away than LeBlanc.

There was so much dust that Clara, who was travelling behind them, didn't see exactly what happened.

"When it settled, I just noticed the bike and her in the ditch, and that was it," she said.

Clara held her sister's body in her arms until someone pulled her away.

More than 178 deaths

CBC's investigation into ATV deaths was prompted by what seemed like a steady stream of police news releases announcing yet another death on a recreational vehicle.

The deaths continued after CBC completed its analysis of the 178 fatal accidents. A little more than a week ago, 13-year-old Marc-André Gionet suffered fatal injuries when he lost control of his ATV and crashed in a quarry near his home in Haut-Lamèque.

Usually, a crash makes news for a day or two. Then it fades, until someone else dies.

The CBC investigation aimed to go beyond the headlines and examine how, where and why people were dying this way.

The analysis showed that most fatal crashes occurred between 6 p.m. and 6 a.m. More than half — 61 per cent — happened on weekends or holidays.

At least 41 per cent of crashes involved alcohol, though that is likely a low estimate.

CBC News obtained information on whether alcohol was a factor in crashes through Access to Information requests, since in some cases police said it would be too difficult to search records and provide contributing factors. No one, not even police, appears to be tracking information in a way that is easily accessible and reported.

In some cases, police know whether alcohol was involved but might not reveal it “out of respect for the families of the deceased,” according to an RCMP spokesperson in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Tens of thousands of users

All-terrain vehicles and snowmobiles are both considered off-road or off-highway vehicles under provincial legislation.

The machines are treated differently from cars under the law, but they can go just as fast and provide significantly less protection to the operator.

The appeal of an ATV or snowmobile comes from getting to see parts of the province that would normally be hidden, riders say.

"Once you ride a snowmobile, you get it," said Ross Antworth, general manager of the New Brunswick Federation of Snowmobile Clubs.

"And when you get it, you're excited about it and you enjoy it. It's a great way to enjoy winter."

But ATVing and snowmobiling are more than just a pastime. They're a way of life in Atlantic Canada, woven into the fabric of rural culture.

They're also a business.

The New Brunswick government estimated that snowmobiling tourists spent more than $17.8 million while visiting in 2014-15. That's just in one province.

The ATV industry contributed as much as $820 million to the Atlantic Canadian economy in 2015, taking into account jobs related to the sale of the machines and other services.

That's according to an independent study commissioned by the Canadian Off-Highway Vehicle Distributors Council, which represents ATV manufacturers and dealers.

Each crash is different. The factors change and collide, and sometimes it’s hard to figure out exactly what went wrong.

But all have one thing in common: every victim left behind someone like June McCullough.

"That's something that most people will not know, how that feels when that person is gone," she said.

"Especially your child. I don't get to put my arms around her anymore."

A fatal crash brings deep grief to people like McCullough, who are left to mourn a child, husband, brother or sister.

But the toll is much larger.

A report from Parachute, a charity that works to prevent injuries, estimated the cost of ATV and snowmobile injuries across Atlantic Canada at more than $42 million in 2010.

Across Canada, the figure reaches $507 million in direct and indirect costs.

That includes the cost of treating traumatic injuries. In New Brunswick alone, hospitals treated 1,143 life-altering injuries related to recreational vehicles in a span of just three years (March 2014 to April 2017), according to data from NB Trauma, a program also trying to reduce preventable injuries.

A call for safety training

Many of the people CBC News interviewed still have questions about how their friend or family member died. They don't know why things went so wrong, so fast.

Some said their relative didn't understand or underestimated the power of the machine. Others said the rider was new to the sport.

Many of those left behind want to see more done to prevent ATV-related deaths, so other people don't have to endure the pain they've felt.

In New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, there's nothing preventing an adult with no experience or training from buying an ATV or snowmobile and going for a ride the next day.

In P.E.I., riding an off-highway vehicle safely is associated with having a driver's licence. For adults there, a training course is only required for those who have had a driver's licence for less than two years.

Only Nova Scotia requires adults to take a safety training course before going out on an off-road vehicle. The rule was grandfathered in and only applies to people born after April 1, 1987.

While there is no clear cause-and-effect relationship, the CBC News investigation found that Nova Scotia, which has a larger population than either New Brunswick or Newfoundland and Labrador, had a death rate of five per 100,000, whereas rates in New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador were eight and 11.5 per 100,000, respectively.

No other provinces in the region have moved to enact blanket mandatory training.

But a group representing the ATV industry says mandatory training is difficult to enforce and could put up a barrier for low-income ATV riders.

"It's physically impossible to be able to train people right across an entire jurisdiction at any time," said Bob Ramsay, the president of Canadian Off-Highway Vehicle Distributors Council.

Both the ATV and snowmobile communities lean toward responsibility falling on the individual rider, particularly when it comes to precautions such as not driving drunk or without proper safety gear.

“We’re always looking to blame somebody. That’s crazy,” said Ross Antworth, who speaks for snowmobilers in New Brunswick.

“Why should it be government responsible to get an individual not to open a beer while on a snowmobile or an ATV?”

The New Brunswick government did not make anyone available for an interview about off-road vehicles.

For Dr. Ian Pike, director of the B.C. Injury Research and Prevention Unit, even the training someone gets to earn a driver's licence would only go so far out in the countryside.

"It's less about being able to negotiate traffic, because that may not be the case in the wilderness or out on the snowfield, but it is about being able to negotiate the environment, which may include trees, rocks, river beds, all sorts of changing environment."

For June McCullough, it's a no-brainer: safety training should be mandatory because ATV riders are operating a vehicle.

She wants the government to act before more families have to endure what she has felt for the last three years.

"How many more people are going to die before it changes?" she asked.

"That's what I want to know. How many more?"

CBC News has clarified a line that appeared in an earlier version of this report. It stated no one, not even police, appeared to be tracking the number of crashes involving alcohol. Police do record the number, however, as clarified, not in a way that is easily known to the public.

CBC News analyzed reams of data and spoke with dozens of families. Here are the stories of just five families who lost loved ones in ATV and snowmobile crashes.