April 15, 2021

CBC's Kory Siegers is spending time digging into stories just like this one that explore issues affecting neighbourhoods around the Anthony Henday ring road. We'd always love to hear your ideas. You can email us at edmontonam@cbc.ca or kory.siegers@cbc.ca

Ken Wegner spent years driving along Anthony Henday Drive frustrated by the acres of weeds that had taken over the fields around it. The thistles, four feet high, were thriving on prime agricultural land.

“I've been growing hay for 50-some years of my life," Wegner said. "That's what I specialize in and that's what I do. I saw opportunity.”

In 2014, Wegner began learning how he could get on the land and make something out of it. He tracked down the property management company and went to work.

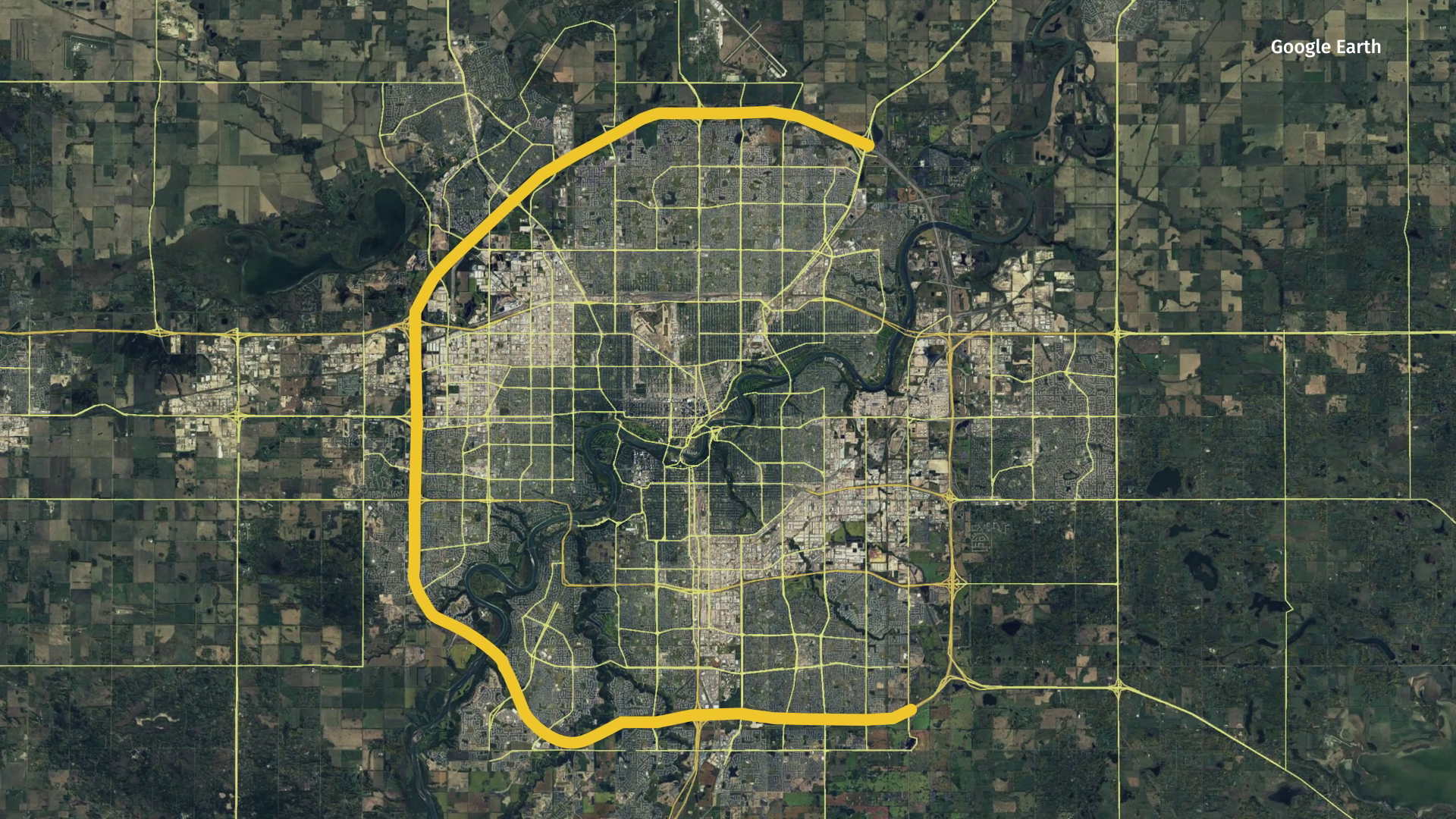

Alberta Infrastructure has 47 agricultural leases on the land around Edmonton’s ring road, known as the transportation utility corridor or TUC. About 4,300 acres is now used for farming, but it’s only in the last 10 years the program has taken off.

Wegner knew it was going to be a big job to get the land ready. It was littered with garbage, piles of iron, steel, concrete and asphalt.

He hired a rider and bought her a horse and for the next two months she rode the Northwest Henday taking photos of the mess.

Wegner took the pictures and compiled a report about what needed to be done before he could get on the land to work it.

He presented it to the government hoping to come up with a plan for the clean-up before signing a lease.

“I believe it was the infrastructure people, the minister's office or whatever, in a big meeting with secretaries and Tim Hortons coffee and doughnuts and everything in the boardroom,” Wegner recalled. “There were a lot of three-piece-suit guys in there and stuff like that, looking at all this.”

The province put the clean-up work out for bids.

Wegner believes the bid prices were in the millions.

“Being a farmer and underestimating the amount of work that was involved, thinking I could do it cheaply, I really underbid that by a lot of money,” Wegner said.

“And I did get it done. And I lost $141,000. And I carry that sticker in my truck to remind me about my mistake.”

Wegner pushed on and began seeding the following summer.

Today he has 22 leases, equaling about 2,300 acres, stretching west from 17th Street to Manning Drive.

The leases vary in size, from eight or nine acres to a large parcel of about 140 acres near Campbell Road.

The logistics are tricky, but Wegner says he takes the good with the bad — the bad being the smaller parcels with poor access, where he has to enter with his equipment through a ditch.

The province rents the land to farmers for $20 to $45 per acre, depending on soil quality and access, said Prasad Panda, Alberta’s minister of Infrastructure.

“It's not the money that we want,” Panda said. “It's more to put the land to a good purpose for usage.”

Many of Wegner’s fields are squeezed between suburban neighbourhoods and the freeway.

“I see a lot of people when we're baling hay or cutting, sitting on their balconies and having a cool one and waving at us,” Wegner said. “I think they appreciate the fact that it's getting cleaned up and it looks like something.”

He does wish more people heeded the no-trespassing signs.

“They figure they can go out and put their sandpit there for their children or grow a garden on the TUC,” Wegner said. “Little do they know that there's high pressure gas lines underneath here ... and it's very dangerous.”

Garbage is another problem — he spends about $15,000 per year cleaning up trash tossed from passing vehicles or illegally dumped.

Wegner says it’s frustrating because he considers the land more than a workplace — it’s his home.

“A big thing about being a farmer is you're not doing it because it's a job. You're doing it because it's an enjoyment to you. It's fulfillment at the end of the season to see nice bales of green hay and that and to sell them to customers that appreciate it.”