January 27, 2019

It all comes down to a click.

One single click, preceded by hours of preparation and inevitably followed by weeks of anticipation, will determine if Peegy Ontong’s family will be complete this year.

If she’s fast, her online request to sponsor her parents from the Philippines to Steinbach, Man., will make its way to federal immigration officers early.

If she’s not, it will get there buried in a virtual heap — likely tens of thousands documents high, with each one representing a family just like hers, all of them wanting to bring a loved one to Canada. Better luck next year.

“I'm envisioning that the site might go down because of the applications that are lining up,” Peegy joked, sitting in her cozy living room in Steinbach.

On Jan. 28, at noon ET — 11 a.m. CT — Peegy will be just one of thousands of Canadians hurrying to fill out a digital form, seeking approval from the government to make a formal application to sponsor their parents and grandparents to immigrate to Canada.

For the past two years, approval was distributed in a controversial lottery system. This year, it’s first-come, first-served.

“It's similar to getting your highly coveted Taylor Swift ticket — like, you got to have the spot,” she said. “And if you don't make it, then someone else will.”

Except the stakes are much, much higher.

Peegy and her husband, Krispin, lost everything when tropical storm Ondoy hit the Philippines in fall 2009. The devastating storm, also called Typhoon Ketsana, killed hundreds in that country and caused millions of dollars of damage.

It left Peegy and Kris with little else but the clothes on their backs and two laptops.

Before the storm, they’d already started the process of coming to Canada through the provincial nominee system. The aftermath of the storm made it easier to leave their home behind, Kris said. They had no choice but to start over, so they did it in the small Manitoba city of Steinbach, about 50 kilometres southeast of Winnipeg.

But leaving their home country and everyone in it was hard.

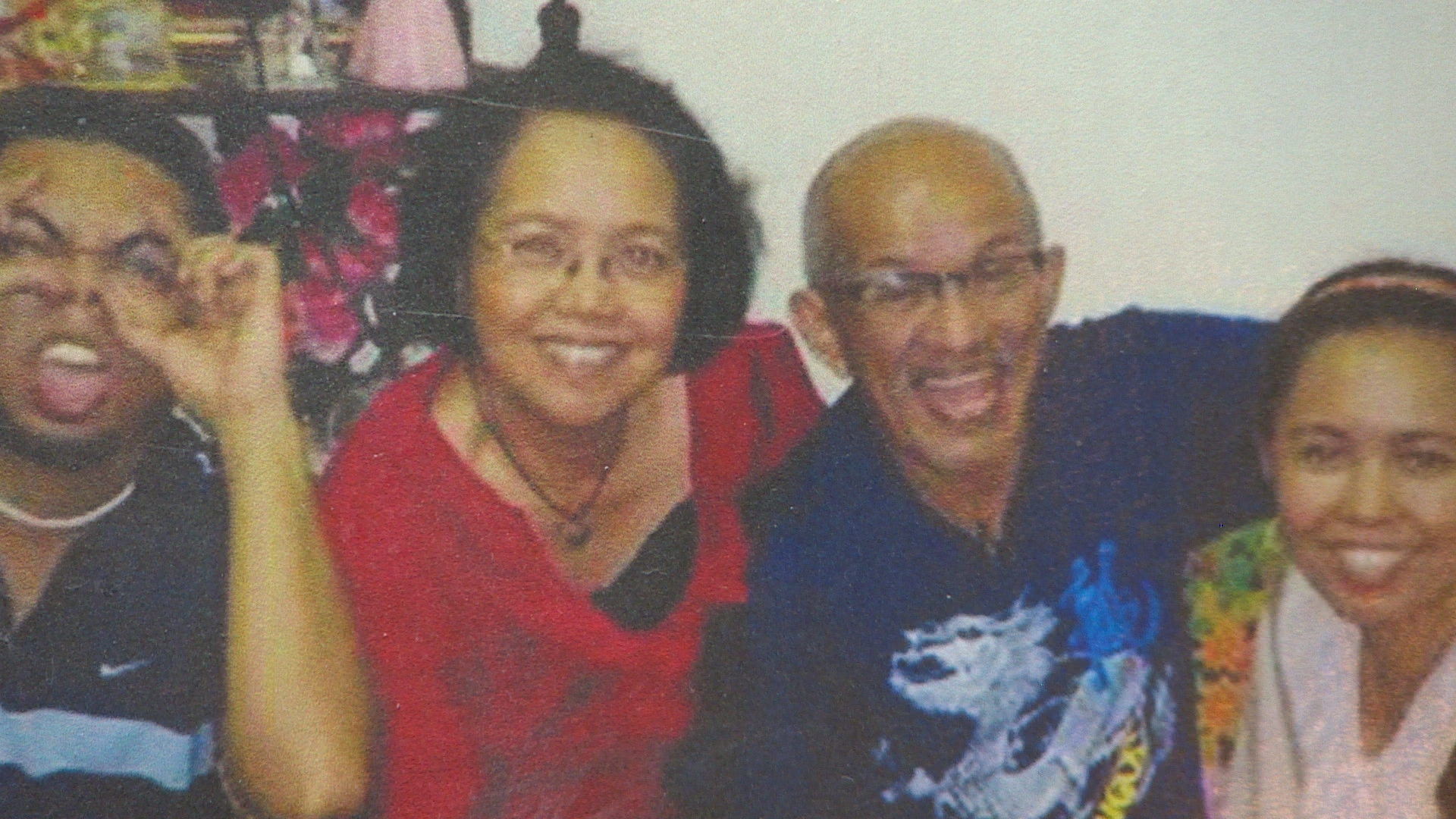

More than anything, Peegy and Kris value being close to their family. In Peegy's hometown in the Philippines she was related to most of her block, and on holidays they’d go down the street, eating at each relative’s house.

“It's that feeling of being complete,” Kris said.

As soon as they could after arriving in Canada in March 2010, they sponsored Peegy’s brother. He now lives and works in Brandon, Man., with his wife and daughter, who was born there.

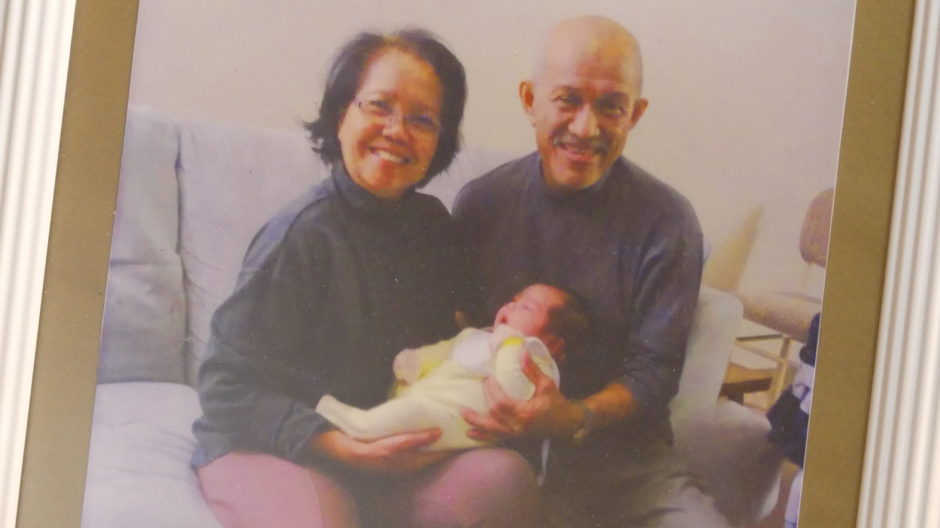

Next they sponsored Kris’s mom, Angelita.

The first time they tried, in 2015, their application was too late. Peegy mailed it, and it arrived just a few days after the application period closed.

So the next year, Peegy tried again, and was successful.

Angelita, or Angie, moved in with Peegy and Kris in 2017 and has lived there ever since. She helps with child care of their seven-year-old, Lexie, allowing Peegy and Kris to work the same hours and spend more time with the family.

Angie was the one who noticed Lexie’s ear for music, and urged Peegy and Kris to sign her up for violin lessons.

It’s the relationship Peegy wants her own parents, Lina and Rollie, to have with her daughter. She laughs when she talks about her 74-year-old dad, Rollie, and his social-media savvy. He’s got four phones, three selfie sticks and a flair for photography. She jokes the marketing firm where she works should hire him.

Lina and Rollie have been to Canada on visits, but that can’t match the closeness the family craves, and what they could have if the grandparents moved here permanently.

“We [could] go out on family outings over the weekends — maybe have a Brandon visit. They can have Lexie stay over for the night, have a grandparents night, you know?” Peegy said.

“Those sort of things that wouldn’t happen if they weren’t here. All we have are just video calls.”

Reuniting immigrant families is one of the priorities Prime Minister Justin Trudeau campaigned on. In 2016, then immigration minister John McCallum announced a “significant shift” in immigration policy toward refugees and reunification, which he said “sends a message about the importance of family.”

In 2017, the Liberal government adopted a lottery system to replace the previous first-come, first-served quota system that required applicants to mail their submissions. The lottery system was supposed to be more fair, but it sparked backlash from frustrated prospective sponsors.

“It doesn't sit well for people, I guess — not just in my community but for other ethnic groups — that you're leaving everything to chance,” Kris said.

“You go through all that trouble of preparing all [that] documentation and then at the end, when you turn it over to Immigration Canada, it's all just luck of the draw.”

And yet, the family planned to do just that this year for Peegy’s parents. Then, in August 2018, the Liberal government announced it was scrapping the controversial lottery system and resurrecting a first-come, first-served system with quotas — this time with an online submission form.

Alongside the announcement that the government would boost the cap to 20,500 parents and grandparents — up from 17,000 in 2018 and 10,000 in 2017 — it was music to Peegy’s ears.

“At least you have a semblance of control,” she said of the first-come, first-served system. “You did your due diligence to have everything ready, just to make sure that you make it to the quota.”

During the 2017 lottery period, more than 95,000 people filled out forms online to bring their parents and grandparents to Canada over the course of a month.

This time around, it’s first to the finish line. And some say that could spell techno-trouble.

Ronalee Carey, an immigration lawyer in Ottawa, says a first-come, first-served system has the potential to be a fair set-up. But if the website crashes — and she’s worried it will — it will plunge applicants into a chaotic scramble that could give people advantages if their browser works better than another’s.

“At that point in time, the system will have failed,” she said. “It will be inequitable and they're going to have to come up with a different way."

There are other pitfalls to the first-come, first-served system, too, she said.

“What if you can’t get the day off work? What if you can’t get internet access at work? How is that equitable?” she said.

“This is not a ticket to a rock concert,” Carey said. “This is your life, and it's all riding on whether or not the system crashes.”

A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada told CBC News in an email the government has taken steps to ensure potential sponsors have "as equal-as-possible" access to the internet on the day, and to prepare for the high volume of traffic on the site.

"The Department has done extensive testing to ensure systems are able to handle the volume," the spokesperson wrote. "However, if anything happens with the system, we will promptly communicate with clients and stakeholders."

Kris is the outgoing president of the SouthEastMan Filipino Association, one of the province’s largest Filipino associations.

When he posted about the opening of the program and the boosted cap on the association’s 800-member Facebook page, he saw the excitement building.

“There was an avalanche of likes for that post,” he said.

Peegy said she knows there will be competition for the coveted spots. She’s meticulously prepared herself to be ready on the day.

“I should be ready with my computer at maybe 10:00 or 10:30, just to make sure that my internet connection is OK, I have all the details in a document that I can just maybe copy and paste,” she said.

“If you don't click fast enough, you risk losing the opportunity this year to get your parents.”

Watch Peegy Ontong submit her form on Jan. 28: