September 12, 2018

Warning: This story contains graphic images.

In a windowless room in the basement of a Montreal hospital, a small army of surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists spent several days in the summer of 2017 engaged in a surreal, choreographed rehearsal over two cadavers.

Dr. Daniel Borsuk and his team were focused on two operating tables set up side-by-side in the centre of the room. Above each table was a surgical light with a sheet of paper taped to it. One was marked "donor." The other, "recipient."

Repeating and refining their technique for hours at a time, they practised incisions and memorized every step from A to Z. They were training for a delicate surgery that, if they pulled it off, would be a Canadian first.

"It will work. There is no plan B."

But their odds were less than ideal. There was a 50 per cent chance the subject could die on the operating table.

That didn’t bother the prospective patient, a 65-year-old Quebec man named Maurice Desjardins, who desperately needed a facial transplant operation. Desjardins understood that the procedure would be long and incredibly risky.

Still, the doctor never doubted it could be done. Or if he did, he kept it to himself.

"It will work. There is no Plan B," Borsuk said.

But nothing was certain about the road ahead. One false step, a single mistake on the operating table, could jeopardize everything. Desjardins would soon find out whether his surgeon’s confidence was justified. He was betting his life on it.

II.

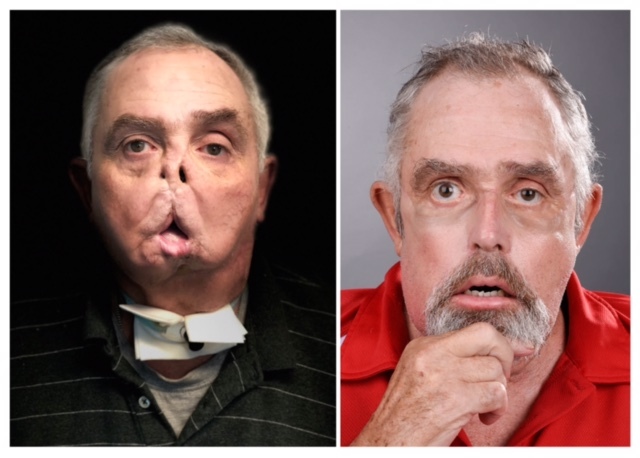

Desjardins was disfigured in a hunting accident in 2011. His injury wasn't just skin deep — the incident severely damaged the nerves, muscles and bones in his face.

He went through four reconstructive surgeries, but despite doctors' best efforts, he was left in chronic pain and struggling with daily life. Since Desjardins had no nose, jaw or teeth, breathing was difficult. Surgeons created an air passage by making a hole in the front of his neck to his windpipe, a procedure called a tracheostomy.

He couldn’t really vocalize, so every time he wanted to speak, Maurice had to press a black button in the middle of his throat, which redirected the airflow around his tracheostomy. Without lips, pronouncing words was difficult.

Meanwhile, eating carried the constant fear of choking.

When he learned of Desjardins’s situation, Borsuk was convinced he could help — that surgery could alleviate the daily struggles and the pain, not to mention improve Desjardins’s overall quality of life and appearance.

The surgeon remembered explaining his proposal — and the risks — in a long conversation with Desjardins and his wife, Gaétane.

"I said, 'Maurice, you could die on the table, or even right after the operation,'" said Borsuk. "He replied, 'Do you think I have a life now?'"

Desjardins was all in, no matter what. Unfavourable odds didn't faze him one bit.

"I am always being judged by others. I'd rather die than keep living like this," he said in the year leading up to his surgery. "I don't care what face I'm going to get, as long as I look like everybody else."

While Desjardins was immediately on board, the procedure couldn't go forward until he'd been thoroughly assessed and cleared as a suitable candidate.

And once he got the green light, Desjardins would still have to wait for the right donor.

"For us, Dr. Borsuk is like a god, because he gave us a hope for a new life."

Borsuk warned the couple that the road to surgery would be a long and challenging one, and it would require their full commitment if it was going to work.

Even the slightest medical setback could derail everything, and the patient’s health had to be in peak condition.

Desjardins agreed to change his lifestyle without hesitation, giving up smoking and drinking practically overnight.

For Maurice and Gaétane Desjardins, what Borsuk was offering went beyond what they thought possible. In the spring of 2017, when preparations were well underway, Gaétane tearfully told CBC/Radio-Canada’s current affairs program Découverte, "For us, Dr. Borsuk is like a god, because he gave us a hope for a new life."

Before they could start that next chapter, there would be months of preparations.

In early 2017, Maurice Desjardins visited the sprawling Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital in eastern Montreal to undergo a week of intense and invasive screening. The team had to be sure he was physically and mentally prepared for the journey on which he was about to embark.

For one thing, the operation itself would last more than a day.

Desjardins was checked for anything that could compromise the precarious procedure: latent infections, cancer and the risk of a heart attack.

Weighing heavily on everyone’s mind was the possibility that Desjardins’s body could reject the donor’s facial tissue, which could lead to death if they weren’t able to find another donor in time. It could happen immediately after the surgery, or even years later.

In addition to the physical evaluations, Maurice and Gaétane met regularly with a psychiatrist, Dr. Hélène St-Jacques. Even though Desjardins had shown complete trust and faith in his doctors, St-Jacques had to monitor his mental state during the preparation process.

What he'd signed up for was no minor thing: In receiving a new face, Desjardins would be getting a new physical identity, and once in place, that change could be profoundly disturbing or upsetting to him.

Borsuk reassured Maurice and Gaétane that his decision to go ahead with the surgery would rely on the word of the psychiatrist. "If ever Dr. St-Jacques says to me, 'Maurice isn't ready,' even if it's the day of the surgery, I will stop everything," Borsuk said. "I am not taking any psychological risks with him."

But Desjardins passed all the tests with flying colours, and moved on to the next stage: waiting for a donor.

III.

No one could say for sure how long the wait for a donor would last. It could be weeks or months.

Since it would be a Canadian first, Transplant Quebec had to create a new protocol to identify the right candidate — ideally, an individual of similar age with roughly the same hair and skin colour. By the winter of 2018, the organization was searching for a match.

Asking for something so exceptional would have to be handled delicately, and it could take time. Transplant Quebec wasn’t asking for just any organ. They needed a family willing to donate their loved one’s face.

Maurice and Gaétane could do nothing but wait for the call. And it came one afternoon in spring 2018.

Given the time of year, the trees were still bare as Desjardins walked into the hospital, holding hands with his wife. The couple had been together for 49 years, and Gaétane had supported her husband at every step of his incredible medical journey. Still, she had her doubts.

A year earlier, she had admitted to Découverte that she was "really afraid that he won’t ever leave the operating table."

"He's alive now, but if this doesn’t work, if his skin rejects the face, what happens then?"

The next time Gaétane saw him, Maurice would be wearing a stranger's face.

Now that a donor had been found, the medical team had to be sure that Desjardins's body and the donor's face were compatible. (It is Transplant Quebec’s policy that the donor's identity remain anonymous.) If the tests revealed that his blood reacted poorly to the donor's cells, everything would come to a halt, and Maurice and Gaétane would resume the waiting game.

That night at the hospital was sleepless. Maurice and Gaétane lay next to one another, cuddling on a bed, waiting for their answer. When morning came, it brought a knock at the door of his room and good news. Dr. Suzon Colette, another surgeon on Desjardins’s team, announced the results.

"We can do the transplant," she said.

Gaétane let out a whoop, and Maurice clapped. But Colette reminded them that a compatible donor did not eliminate the lifelong risk of rejection. To stop his body from rejecting the graft, Desjardins would have to take powerful immunosuppressants for the rest of his life — and that still would not eliminate the threat entirely.

Twenty-four hours later, Desjardins was on a gurney, being wheeled into surgery. Gaétane followed behind, caressing her husband’s head. This could be their final goodbye. The odds of his survival might as well be a coin toss.

If Desjardins did pull through, the next time Gaétane saw him, he would be wearing a stranger's face.

Just outside the doors of the operating room, they stopped the gurney. Borsuk asked if Desjardins had any questions. He did not. Desjardins simply looked up at the doctor and said, "Good luck."

His words immediately cut the tension. Everyone broke into laughter, including Gaétane, who was holding back tears. Borsuk put his hand on Desjardins’s shoulder.

"We're all here for you, OK my friend?"

"I have faith in you guys," Desjardins answered, wiping away a tear and giving his surgeon a thumbs-up.

IV.

Borsuk and his team now had to put into practice the complicated manoeuvres they'd carefully rehearsed all those months ago.

Taped to the wall of Desjardins’s operating room were five poster-sized pages outlining the play-by-play steps for the maddeningly complex surgery they were about to perform.

Across the hall, another team was setting up for a parallel procedure — the one to remove the donor’s face.

Before starting, Borsuk asked for everyone’s attention.

"OK, guys: a little minute of silence. We're going to thank the family and the donor. They have been extremely generous," he said. After a brief pause, the marathon surgery began.

The transplant would not just involve grafting skin. The team would have to remove the donor's jaw, teeth, nose and cartilage — all in one piece. There was no room for error.

Six hours into the surgery, Gaétane, sitting in the waiting room, was struggling to match the confidence her husband had shown going in. She echoed the same fear she’d shared with Radio-Canada months earlier.

"I'm afraid. I'm really afraid that he won't leave that operating table," she said, a flannel hospital blanket draped around her shoulders.

In Desjardins's operating room, the procedure had reached its decisive moments. The team was carefully reconnecting the veins and arteries of their patient’s new face. If the blood didn't flow properly, the graft would die.

Immediately after the blood vessels were reattached, an uncanny moment unfolded. As all eyes fixated on Desjardins’s new face, his skin gained a healthy blush, and the lips turned from blue to red.

The tension in the room eased, and the team did its final sutures. Not only had Desjardins survived, the team had pulled it off without a hitch. Many members of the team hadn’t dared to imagine that level of success.

In all, it took 16 hours to prepare Desjardins’s face, 12 hours to remove the donor's and 18 hours to transplant the graft.

When they finished, applause broke out. Borsuk turned to congratulate his team.

"All right, guys. Thank you for everything. Thank you, nurses. Amazing! The team was unbelievable. Amazing experience! Maurice will be really happy!"

V.

Desjardins wasn't able to hear the good news right away. To avoid any undue suffering, he remained in intensive care, in a medically induced coma, for several days.

Once he was awake again, every effort was made to ensure he didn't catch a glimpse of himself before the grand unveiling. Even the windows in his room had been covered.

No one spoke when, two weeks later, Borsuk walked into room 609 in the transplant ward of Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, holding a mirror. Desjardins was sitting up in bed, and took the mirror into his hands. He peered into it, furrowed his brow, looked up at the surgeon and then back down at his reflection.

Dr. Daniel Borsuk shows Maurice Desjardins his newly transplanted face for the first time after the surgery. (Radio-Canada)

He tried to speak, before remembering that he couldn't.

Smiling at his patient, and holding his shoulder, Borsuk asked, "So, what do you think?"

Desjardins answered the only way he could — with a thumbs-up.

The two men embraced.

“You’re the best, Maurice!” Borsuk said. “You’re the best!”

At a press conference on Wednesday, Borsuk reflected on the moment Desjardins saw his new face for the first time.

“If you’ve ever seen a small child look in a mirror — it’s that," said Borsuk. "Touching his nose, touching his lips, and it’s almost... disbelief."

Borsuk said that was the moment when the meaning of the whole procedure really dawned on Desjardins. “When he finally looked in that mirror, it really... hit home. Everyone in the room, the security guards — we were all crying. It was very emotional.”

After two months of recovery in hospital, Desjardins was transferred to a physical rehabilitation centre. He's still relearning how to eat and speak. For the rest of his life he'll have to take immunosuppressants, which will leave his body defenceless against even the most innocuous infections.

He's grown a beard — something he couldn't do before his surgery — and he's already well enough to go out on strolls with his wife.

Desjardins still can't speak, but the success of his transformation is written across his face.