December 9, 2018

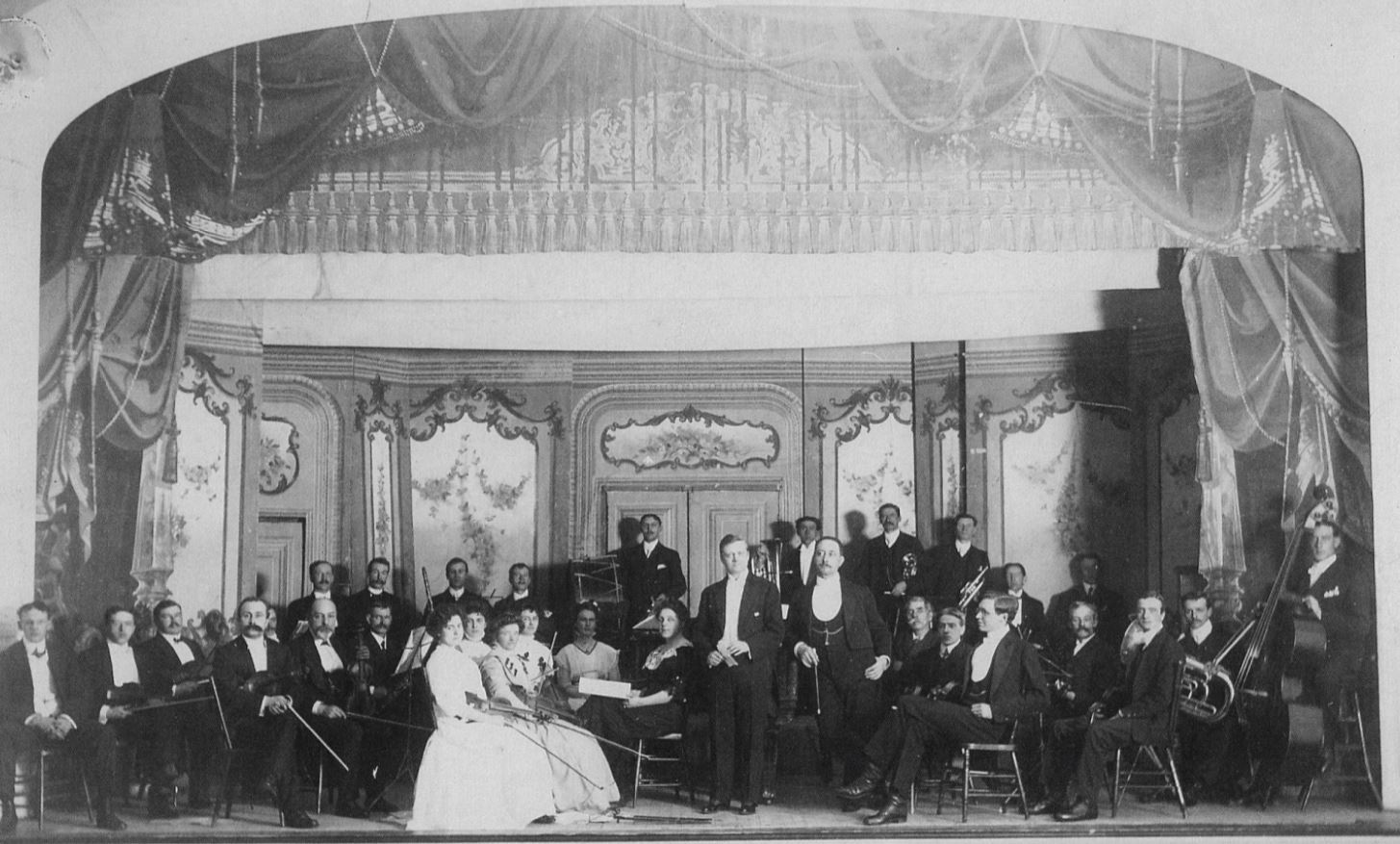

For the Regina Orchestral Society’s inaugural concert, 32 musicians performed a selection of 10 classical pieces in a space designed to contain the echoes of city council debates instead of the crescendos of Mozart and Bach.

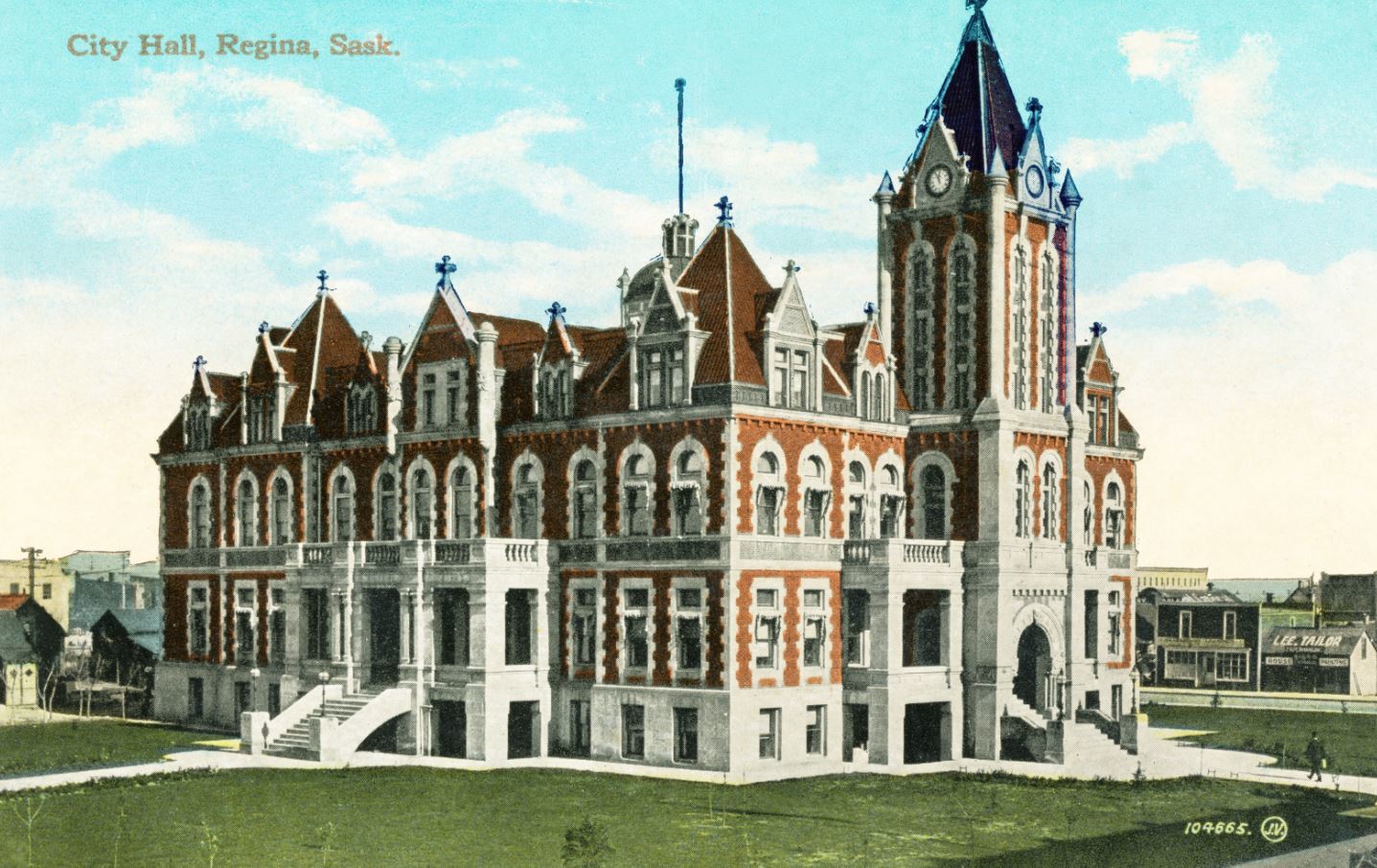

It was Dec. 3, 1908, and the Regina Symphony Orchestra’s predecessor was performing in the “Gingerbread” City Hall — the fledgling prairie city’s first municipal government building, then located at 11th Avenue between Hamilton and Rose streets.

The orchestra wasn’t the only thing making noise that night. As the musicians worked through Robert Schumann’s The Two Grenadiers, Edvard Grieg’s Iche liebe dich and Francis Thome’s Simple Aveu, they had to contend with the chorus coming from the jail housed in the basement of City Hall. Prisoners clanged their cups against the bars, and even cat called throughout the night.

Still, The Morning Leader newspaper said the concert was “unquestionably a great success,” calling it “undeniably brilliant and striking.”

“We hope this is only the first of a series of orchestral concerts,” it wrote.

And it was.

Later that month, the orchestra performed Handel’s Messiah, which would become an annual tradition the symphony maintains to this day.

Although the Regina Symphony Orchestra has changed venues a handful of times over its 110-year history, the reasons for its survival and growth over the course of two world wars, the Depression and financially trying times has remained the same: passionate community members dedicated to seeing Regina’s musical scene flourish.

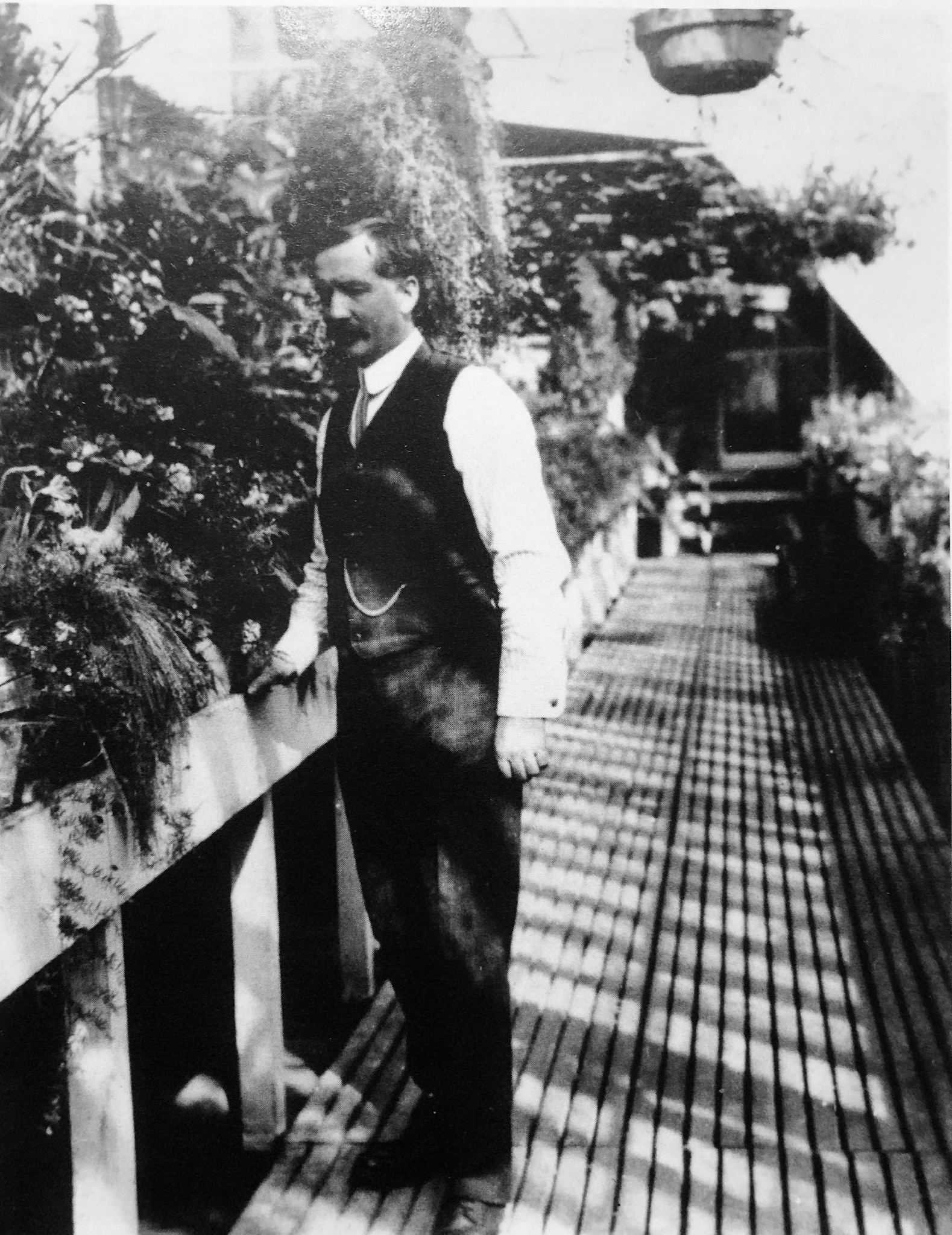

On Aug. 25, 1908, George Watt watered the greenhouse at Government House, stacked chrysanthemums and used a scythe to cut weeds by the fence along the street. The resident gardener — and flutist — then attended a Regina Orchestral Society meeting where the organization’s first rehearsal was being planned.

“George Watt’s diaries are fascinating, because I don’t think there are many records from people that are personal accounts of their activities during that period of time,” said Dave Hedlund, a Regina Symphony Orchestra board member who has been collecting archival material about the organization.

Listen to Hedlund speak with Saskatchewan Weekend guest host Peter Mills here.

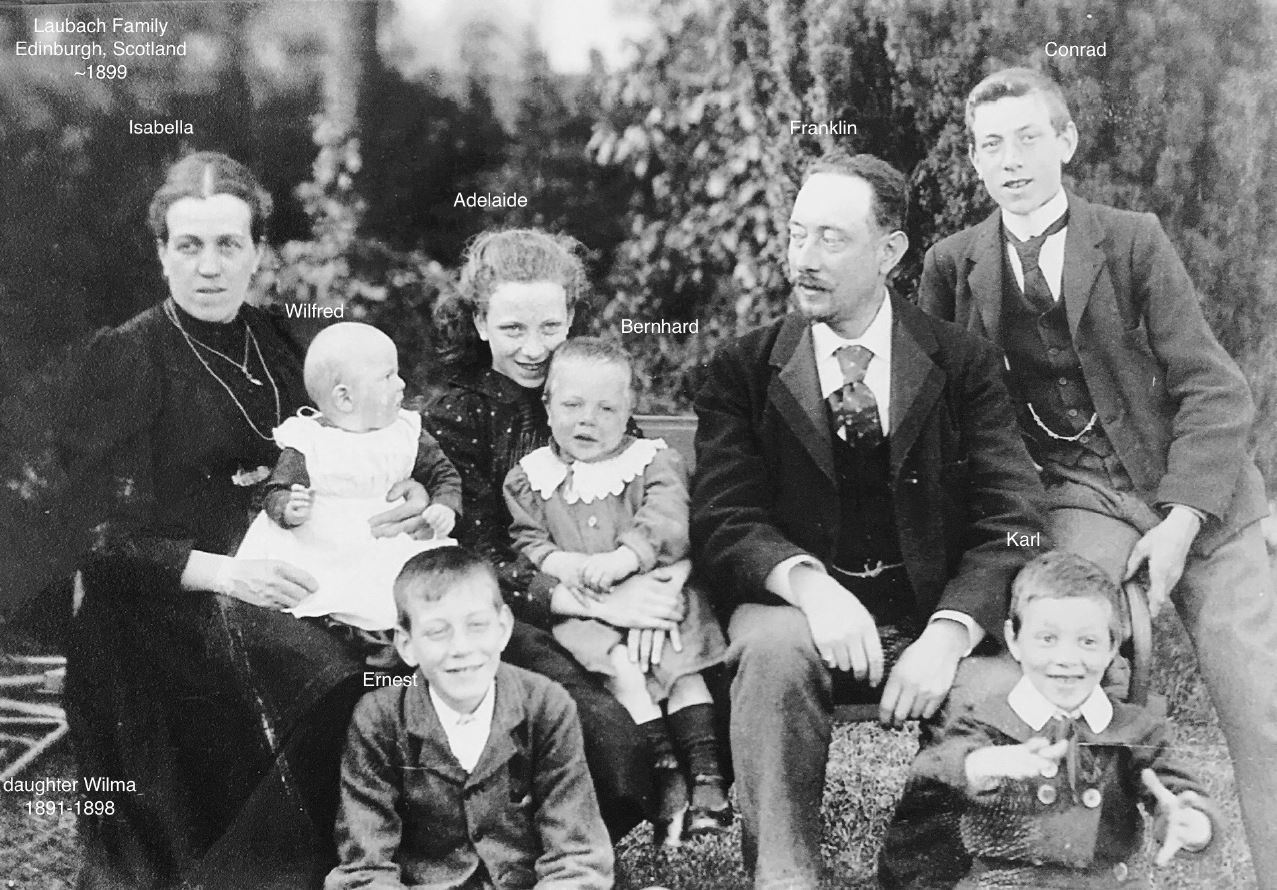

But it was Franklin Laubach who would become known as the Father of Regina Music. Laubach came from Edinburgh, Scotland, with his wife and six children in 1904. He was the conductor of the Leith Orchestra and president of the Edinburgh Society of Musicians.

The Laubach’s first farm home was more like a shack, so they had difficulty keeping their instruments dry from the rain. They eventually moved into a house in what is now Regina’s Cathedral neighbourhood. Franklin's daughter Ada noted they could see all the way to Moose Jaw, Sask., from their home.

Of the many roles he filled, Laubach co-founded the Regina Philharmonic Society, the Saskatchewan Provincial Music Festival, and was appointed as one of the first music department faculty members at Regina College.

Despite The Morning Leader’s pronouncement that “the steady interest taken in musical matters is always a healthy sign Regina bids fair to become the musical centre of Saskatchewan,” the Orchestral Society would have to contend with major forces over the course of its first few decades.

When the First World War broke out, Laubach and his four sons were conscripted to serve overseas.

Even so, the orchestra played on, but not as regularly.

Then the Spanish Flu hit. The City of Regina banned people from gathering in groups. The orchestra couldn’t get together.

“So performances were out. Practising was out. But these people still practised in their homes,” said Jackie Schmidt, the vice-chair of the Regina Symphony Orchestra board.

“Because of the tenacity of all these people, they were not going to let this [orchestra] die, because music is such an important part of their life.”

As the war wound down, Laubach started rehearsing with the orchestra again.

He also began a war of his own: For a new venue.

In December 1919, Laubach wrote a scathing letter to the editor for The Morning Leader. In it, he says that during his time in Regina “there has been nothing done by the city to promote culture or to help the people lead happy and temperate lives.” He wrote that, not only the orchestra, but other music organizations formed since required better practice and performance spaces.

Laubach moved to Vancouver in 1922 and died there the next year, having never seen his request come to fruition.

Before the Depression hit, though, a blessing: in 1924 Francis Darke donated $100,000 to build a new music and arts building for Regina College.

The Depression itself affected the Orchestral Society in much the same way it did its musicians, who were finding it hard to make ends meet: Annual budgets got smaller and smaller.

“One person couldn’t afford to feed his family. His family was living with his in-laws. He was still on the board,” said Hedlund. “He was still doing what he could to keep music alive in Regina.”

The Second World War saw the orchestra fraught by a similar stop-and-go as the Great War. The conductor at the time, Knight Wilson, joined the army. Since he was transferred, the orchestra board put performances on hold indefinitely. Then the Conservatory of Music stepped in and provided leadership.

“They didn’t know if they were going to be doing that for the long haul or not, but they made sure some of the people who wanted to play and some of the people who wanted to listen to orchestral music still got to do that during war time,” said Hedlund.

Years later, one of the orchestra’s future concertmasters, Malcolm Lowe, was fortunate enough to see the orchestra at its first permanent home.

“I remember vividly sitting in the second balcony in Darke Hall before I played with the Regina Symphony Orchestra,” he said.

He credits his first orchestral experience with his decision to pursue a career in music. He remembers the rehearsals more than the concerts. He was curious to listen to what they were working on.

“Without that experience even at a young age, and even though I didn’t know what that meant being a concertmaster, I wouldn’t have ended up as concertmaster of the Boston Symphony if I had not had that.”

Lowe’s family, like the Laubachs, was one of many that played together in the orchestra over the years. His two brothers and sister, along with his parents, were involved. He likens it to a family being on a sports team.

“We would go home after a concert whether everyone played or not. We were all wondering what the other family member was doing or thinking in that passage or at this moment or that moment,” he said.

Lowe ending up serving as Regina Symphony Orchestra’s concertmaster from 1975-1976 — a time when the organization faced incredible financial challenges and simultaneously had a conductor who dreamed big.

Hedlund recalled one of the ambitious projects was putting on Madama Butterfly. It lost a lot of money. For two consecutive years, the orchestra had a deficit of about $800,000 in today’s dollars.

Alan Denike, who played as the orchestra’s principal bassoonist for 42 years, recalled one of the lowlights was when the string players were fired because of the deficit situation.

“Luckily they were quickly rehired when it was realized that they could maybe run the office through the volunteers, with the chamber players,” he said. “We volunteered to help out for free, as did the women’s association with the RSO. ... That went on for a couple of years before they hired office staff.”

Hedlund admired everyone who stepped up during economically challenging times. He remembers board members selling citrus fruits, putting on fantasy auctions and a symphony ball.

“That’s why we’re still here 110 years later, because many times people met the challenges with the insistence that we had to have a strong and vibrant culture of music in our city.”

The future of the orchestra is in good hands with prospects coming from the South Saskatchewan Youth Orchestra, which is in its 42nd season. About 50 per cent of the current Regina Symphony Orchestra is alumni from the youth contingent.

Denike has been in charge of the youth orchestra for the past three decades. He said his experience playing in the National Youth Orchestra of Canada influenced him to make a career out of music.

Some of the alumni have landed jobs across the country and even abroad, including New York and Amsterdam. Lowe’s brother Darren was also part of the youth orchestra. Today, he is the concertmaster of the Quebec Symphony Orchestra.

Schmidt said the youth orchestra helps youth figure out what they want to do with music at an early age — and, in many cases, gets them hooked so they join the ranks of those committed to the larger music scene in Regina.

“Once you’ve been involved in music, it takes a hold of you and it’s a part of your life. I feel sorry for people who don’t have music in their life all the time. Because it’s such as a major important element. It has such a positive force on people. That could also speak to why we have it here. Once you get it started, you just can’t stop it.”