December 2, 2021

For weeks, the pressure was mounting with no easy fix in sight.

It’s June 24, and managers and executives within Eastern Health are scrambling to find space at two St. John’s hospitals where there is none.

“Surgical interventions have been cancelled every day at [the Health Sciences Centre] and [St. Clare’s Mercy Hospital] due to staffing issues and bed availability,” says a briefing note prepared for Debbie Walsh, a vice-president of Eastern Health.

“Patient volumes and delays have placed patient admissions, surgical lists and interventions at risk.”

All nursing units at both city hospitals were “critically short,” the note states.

CBC News requested documents and data on the number of Code 111 meetings called during June and July, when capacity at the emergency room of the Health Sciences Centre was front and centre on social media as patients waited extraordinarily long times to be seen by a doctor.

The emails paint a grim picture of a system in crisis mode: at one point patients waited up to 31 hours for a bed.

Code 111 meetings were called when the health authority needed to immediately address critical overcrowding, or when capacity was soon expected to become an issue.

There were 13 Code 111 meetings scheduled between June 1 and July 31 at the Health Sciences Centre.

Hundreds of pages of documents show what was happening behind the scenes while patient complaints were being aired online. The question now is what's being done to address the issue?

‘Unprecedented’ number of patients flood ER

During one week in late June, “the acute care, city hospital facilities have seen unprecedented presentation of patient volumes through their emergency departments,” wrote Michelle Alexander, regional director of clinical efficiency.

Alexander explained the higher number of admissions was driving ambulance offload delays at the emergency room, causing further problems as paramedics became tied up at the ER instead of responding to calls.

The issues persisted throughout the next week.

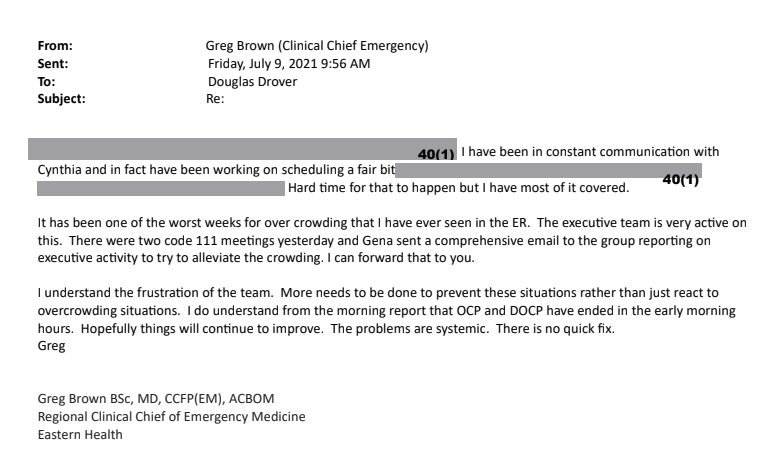

“It has been one of the worst weeks for overcrowding that I have ever seen in the ER,” wrote Dr. Greg Brown, regional clinical chief of emergency medicine, on July 9.

“I understand the frustration of the team. More needs to be done to prevent these situations rather than just react to overcrowding situations… Hopefully things will continue to improve. The problems are systemic. There is no quick fix.”

Doctor, doctor

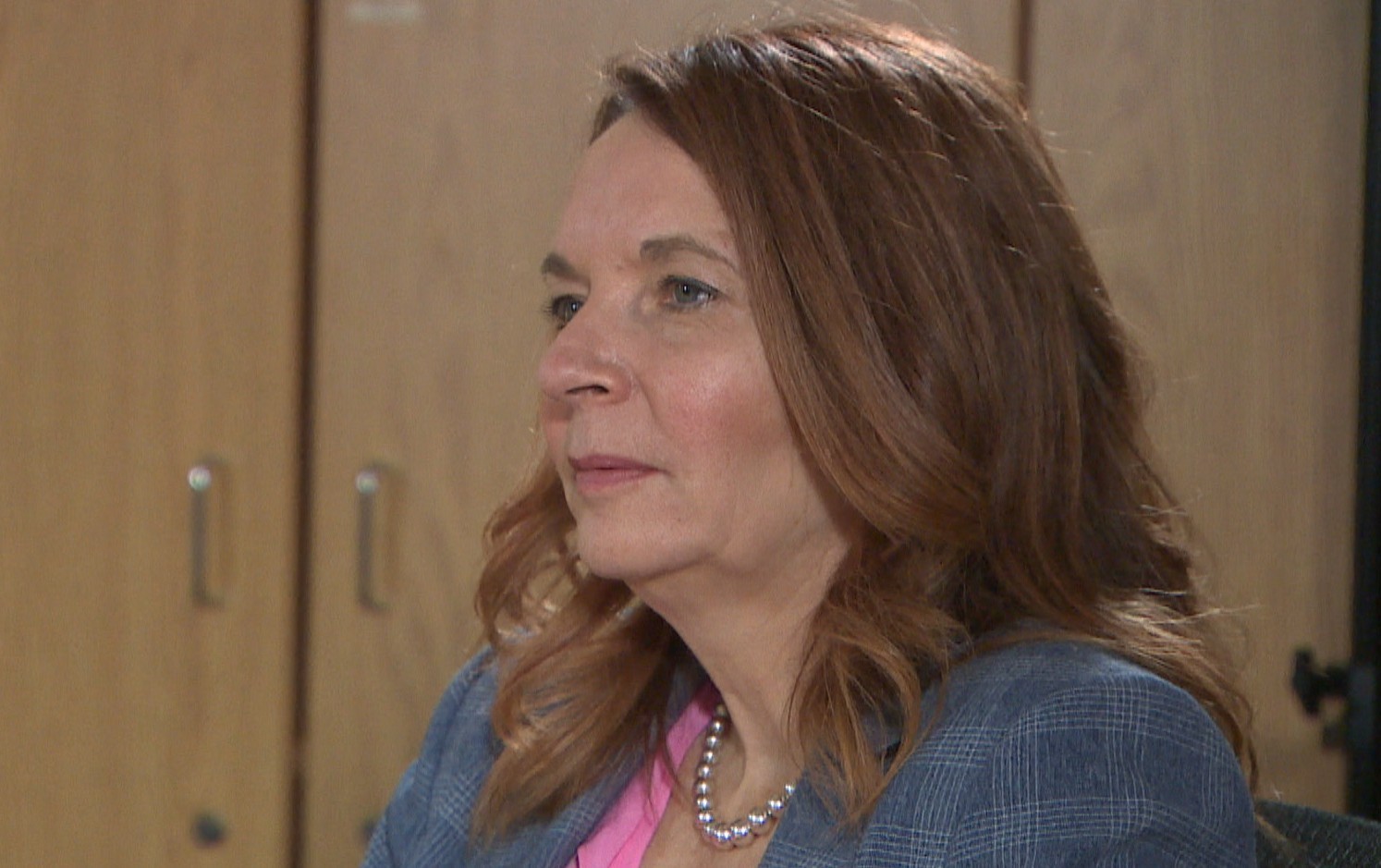

Six months later, Liz Kennedy, executive director of adult emergency programs, looks back and is glad that period of time is over.

“It was definitely one of the most challenging periods for that week or more, consistently. We have seen in the last six to eight months the numbers of patients coming to emerg are really back where they were prior to COVID,” Kennedy said during a recent interview.

But capacity, she says, remains an issue.

There is not one factor that contributed to the mass number of patents coming into emergency rooms, Kennedy says, but many. She references the need to give nursing staff time off, especially given the long, arduous hours they worked during the pandemic.

Combine that with a lack of family physicians, and capacity reached critical levels.

“We’ve heard numbers out there on the number of people without a doctor. I think it’s close to 100,000 so we definitely get the sense that a lack of an access [to a] GP is certainly impacting people’s ability and they’re coming to [the emergency department,” she said.

Working inside the ER

For one St. John’s doctor who works inside the system, a shortage of family physicians means there will be a continuing crunch in the waiting room of the emergency department.

Dr. Steve Major has about 2,000 patients at his practice on Campbell Avenue in central St. John’s. He’s been doing regular shifts at the emergency department at the Health Sciences Centre and St. Clare’s since 2001.

Lately, his two worlds have been colliding.

“If you have a medical issue and you have nowhere else to go, emergency is your last last opportunity for health care. That's where our system is set up,” Major said during an interview at his office.

“But unfortunately, it ends up putting a lot more stress on the emergency department because patients that could be seen by a family physician are now seen in an emergency, which is probably not the best place for them to be seen for those with more minor or or long-term chronic illnesses.”

Not only is Major seeing more patients, he’s seeing sicker patients — some past the point of saving.

“We're seeing people who are presenting with metastatic cancer, whereas if they had a primary-care provider that might have detected it earlier than they might have more of a chance,” Major said.

Major stresses the importance of the provincial government doing more to recruit and retain new doctors, beyond the already-announced collaborative clinic teams.

He said a lack of general practitioners is costing the province financially, but it’s the human cost that worries him most.

“People are suffering because they can't get the care they need and people are dying, probably, because they're preventing this more advanced illness. And that advanced illness is then not curable.”

No doctor. Now what?

What Major sees in a professional capacity, the Murphys of Bay Roberts are living in their personal lives.

James and Tracey Murphy have had to go to the emergency room, in both Carbonear and St. John’s, on a handful of occasions, at times leaving after an eight-hour wait.

“The doctors that are on staff there, they’re swamped,” said James Murphy.

“The nurses that are there are overworked. Working overtime and doing a double shift. As a patient walking into that doesn’t really leave you feeling very… what's the word? Relieved.”

That was before they lost their family doctor in September.

“I don’t have that luxury now of calling my doctor to get an appointment, I don’t have the luxury of getting my necessary testing done,” said Tracey, who has an autoimmune disorder.

“I can make arrangements to go to an ER to get the testing done but I have no one to deal with the results of said testing. So it’s one thing to get it done but when you have no way to get the results, you have no way to continue proper treatment.”

The Newfoundland and Labrador Medical Association says recent polling shows the number of people without a family doctor is approaching 99,000. That’s one in five people in the province who don’t have access to a general practitioner.

Tracey Murphy says her medical condition is such that a 811 call won’t suffice. James Murphy needs regular testing and monitoring for his diabetes.

They say they’re left with no other option but to go to the emergency room for health care while they search for a new family doctor.

“We’ve tried in St. John’s, we’ve tried Holyrood, we’ve tried Carbonear, we’ve tried Whitbourne, we’ve tried Victoria,” Tracey Murphy said.

“Nurse practitioners are taking appointments four weeks in advance and they also have their own patients.”

Struggle for RNs continue

Yvette Coffey, president of the Registered Nurses' Union Newfoundland and Labrador, says her members are still struggling through staffing shortages and capacity problems.

During the summer, Coffey spoke publicly about how understaffed long-term care facilities in St. John’s were, and warned of the consequences on patients.

In June, Eastern Health stopped admitting new patients to four long-term care homes in St. John's due to nurse shortages.

At the time, Coffey said, there were 50 registered nurse vacancies in long-term care.

“The current situation hasn’t changed,” said Coffey in an interview late last month.

Coffey said the province is down 500 nurses. She suspects that number will increase as more nurses leave the profession due to stress, and retirements.

“Every RN in this system and our patients deserve better. Because when you have physically and mentally exhausted nurses your patients are not getting 100 per cent care and attention,” Coffey said.

The Paramedic Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, however, has seen an improvement since the summer.

But association president Rodney Gaudet says offload delays are still commonplace.

“[Paramedics] can't just simply drop the patient onto the floor or into a bed that's not being staffed by nurses,” Gaudet said.

“So then the paramedics are stuck there with the patient, providing care, continuing to provide medical care until a bed becomes available.”

Over four days in June, 54 ambulances spent an average of more than two hours in offload delay, just waiting to drop off patients. The longest wait was 8½ hours.

Having paramedics tend to patients in the emergency room is not a good use of their time, Gaudet said. It means there are fewer ambulances on the road, which can lead to an increased number of red alerts — when there’s no ambulance available on standby and ready to take a call.

New paramedics were added to the St. John’s complement in November.

But Gaudet said the issues faced by health-care professionals, like paramedics, are still not addressed.

“We can't just turn our backs to it and say it no longer exists at all because it is still there. And so we need to continually look at it and constantly be looking at it and constantly making changes.”

Taking a proactive approach

Eastern Health’s Debbie Walsh, who oversees clinical efficiency, says officials are reframing the way the health authority views patient flow.

One of those changes happened after the capacity crunch in the early summer.

The health authority no longer holds emergency Code 111 meetings, when a crisis is looming. Instead, Walsh says, every morning the clinical team meets to assess hospital capacity in an attempt to stop overcrowding before it happens. Not just at the emergency level, but in every department.

“It’s much more proactive and as well we’ve seen the benefit of that. It embeds that conversation every day into our clinical leadership team,” Walsh said.

Walsh said a new visual management system has been introduced that allows staff to see exactly where patient flow is tight, or where there is space, in real time.

In the long term, Kennedy says, she is encouraged by the promise of an extended emergency room at the Health Sciences Centre. The emergency room currently can hold up to 33, but that include hallway spaces. The expansion will increase that number to 50.

Though space is needed, Kennedy says addressing the doctor shortage would go a long way in assisting all aspects of the health-care system.

“To say to people who’ve had a lengthy waits in the at emerg, we’re really sorry for the experience,” Kennedy said.

“We want to reassure them that this is something we’re really focused on and want to improve because it could be us in the emergency room any day or our loved ones.”