October 28, 2018

In hundreds upon hundreds of photographs, and pages upon pages of notes, a prominent Winnipeg doctor set out to prove he was communicating with the dead.

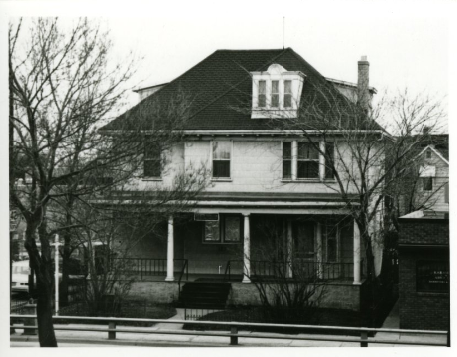

In his grand home on Henderson Highway, T.G. Hamilton built what amounts to a ghost laboratory in the first decades of the last century: a locked room, an open cabinet, more than a dozen state-of-the-art cameras.

Their star-studded guest list included Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a Nobel-prize winning scientist and a former prime minister of Canada.

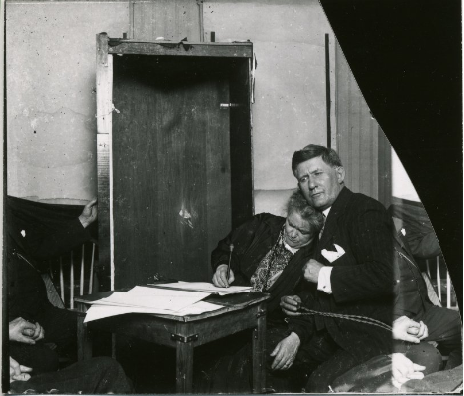

Mediums and guests alike were searched before they entered and asked to sign witness statements before they left. His wife, Lillian, wore the key to the room around her neck.

The seances started as an anguished mission to talk to their son, Arthur, who died of Spanish flu in 1919 at only three years old.

But as their “home circles” gained international success and fame, the focus of the project shifted, said Serena Keshavjee, a University of Winnipeg art historian who has done extensive work on Hamilton.

By the time of his death in 1935, Hamilton and his family were working to prove, scientifically, that ghosts are real and we can talk to them.

Shelley Sweeney, head archivist at the University of Manitoba Archives, said it appears T.G. himself and others like him were genuine believers.

“I think that people believed that there was life after death — and that if they could just open the door a crack, they might be able to find out how their loved one was doing.”

Thomas Glendenning Hamilton, sometimes called T.G.H., was born in Agincourt, Ont., to Scottish parents in 1873, and later moved with his family to Saskatchewan.

After the death of his father and sister, he and his brother eventually landed in Winnipeg, where T.G. attended medical school and became a doctor — and later, a husband and father.

He married Lillian Forrester, a nurse from Emerson, Man., and the pair had four children. Hamilton was a prominent physician and community leader: deacon of his local church, president of the Manitoba Medical Association.

He was an MLA in the Manitoba Legislature for six years, a school trustee for nine years and the provincial representative on the board of the Canadian Medical Association.

In 1918, a professor friend introduced Hamilton to the paranormal and Spiritualism — a movement that saw its peak in the late 1800s and early 20th century.

The following year, his son died of the flu pandemic that gripped the Western world.

“It’s very traumatic for the entire family,” said Sweeney.

“Probably because Hamilton was a doctor, he was particularly, I think, anguished by the fact he was not able to save Arthur.”

From there, the family’s interest in the paranormal grew. By late 1920, T.G. and Lillian had started their own experiments at home, with the help of their children's nanny, Elizabeth Poole, who was a medium.

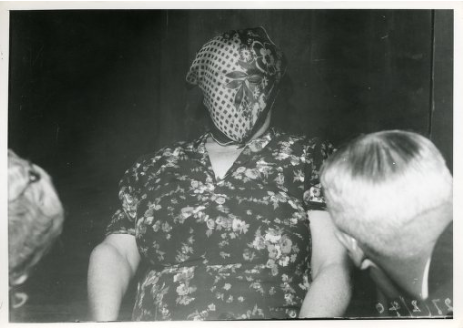

The experiments initially focused on telekinesis — remotely moving objects. A few years later, they expanded to home circles, also called seances, and added two additional mediums: Mary Marshall and her sister-in-law Susan Marshall, also called Dawn and Mercedes.

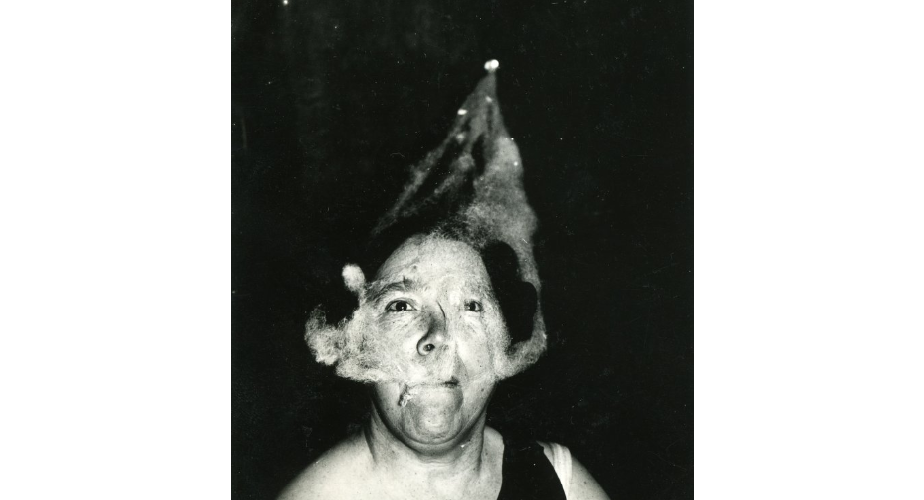

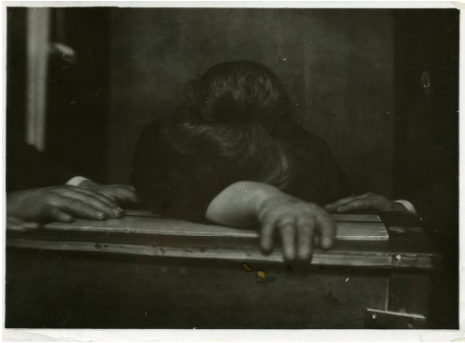

That’s when, according to Hamilton's reports, they started to see ectoplasm — spooky white masses, alleged to be the physical manifestation of spirits, emerging from orifices on the mediums’ faces and visible only in photographs.

Each seance was diligently photographed by the bank of cameras Hamilton purchased, at great expense, and modified so they could be operated by someone seated at the table.

In the interest of scientific rigour, they invited prominent guests, including celebrated Winnipeg doctor Bruce Chown and lawyer Isaac Pitblado.

As Hamilton's fame grew, so did his guest list: former prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, Nobel Prize-winning physiologist Charles Richet and Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle all attended.

After Conan Doyle’s death, his wife returned to speak to him through the medium.

The mediums weren’t paid for their work, and records indicate T.G. Hamilton himself was earnest in his belief, Sweeney said.

Reports of the paranormal phenomena continued for a decade after Hamilton’s death in 1935 — a fact which draws into question the notion that Lillian had rigged the images to make her husband feel better after their son's death, Sweeney said.

“So the question is,” Sweeney said, “if there was fraud in the room, who perpetrated it?”

When Hamilton began his paranormal investigation, many in the Western world were grieving: roughly 60,000 young, healthy Canadians had died in the First World War, and thousands more were killed by the Spanish influenza pandemic in 1918 and 1919.

“What you get is a worldwide phenomenon of people trying to make contact with their dead relatives, or dead lovers, or dead children,” Sweeney said. “This is not an isolated incident.”

Hamilton was part of an international revival of modern Western spiritualism, Keshavjee added. He gave more than 80 talks across North America and Europe, and was supported by the work of several other paranormal scientists, many with backgrounds in medicine.

At the time, cameras were considered a neutral eye, she said. The mass development of photographic technology — and the ability to capture split-second images thanks to improved flash bulbs — came hand-in-hand with the revival.

“The camera, then, is the proof. And that’s what Hamilton thought - his photographs were evidentiary proof of materializations,” Keshavjee said.

“It took the invention of that technology to allow scientists to see ghosts.”

After Hamilton died in 1935 from a heart attack, Lillian continued the experiments until 1945.

Sweeney said she doesn’t believe Hamilton was ever psychologically imbalanced, or driven insane by grief. Despite his public interest in the paranormal, it appears he wasn’t dismissed as a kook.

“Maybe, OK, everybody didn’t necessarily believe what he was saying,” she said. “But I think that they would have been persuaded by his passion and his anguish.”

Sweeney said it’s not clear exactly why the experiments wound down — although the tide of public opinion had shifted against them by 1940 — or whether the family really did get comfort from their work.

She wants to see more research done to answer those questions.

“Whether you believe that this was real or you believe that it was faked doesn’t matter,” she said.

“This was a social phenomenon that was occurring all around the world, and it was not simply … one single family in one place.”