December 25, 2018

Search "Chief Allan Adam" online and photos pop up of the Indigenous leader with celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Jane Fonda and Daryl Hannah. When Hollywood stars travel to northern Alberta to voice their disgust with the oilsands, the chief of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN) is usually their tour guide.

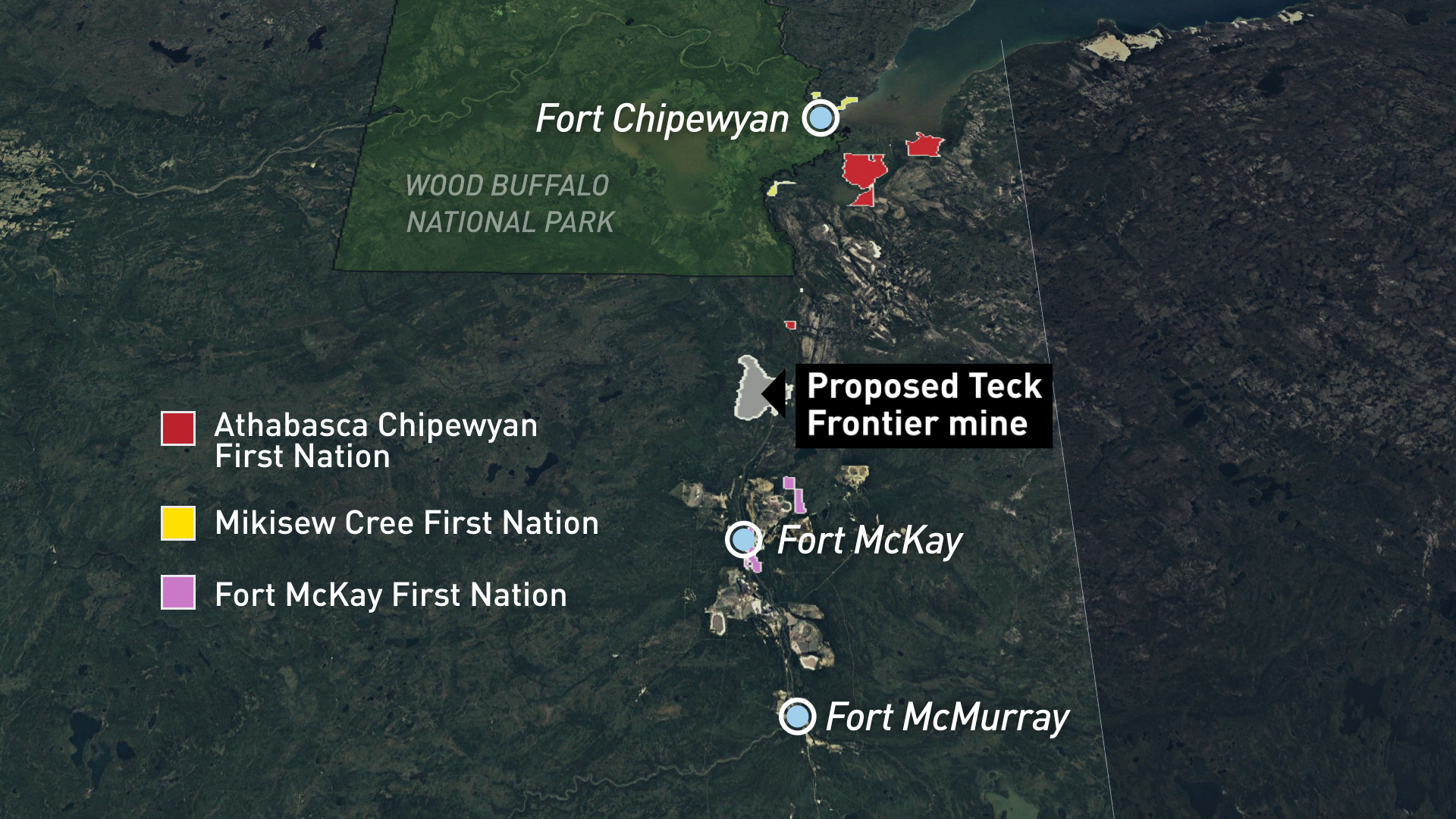

Adam and his people are based in Fort Chipewyan, an isolated community that is a 40-minute flight north of Fort McMurray, Alta., and downstream from the region's massive oilsands developments.

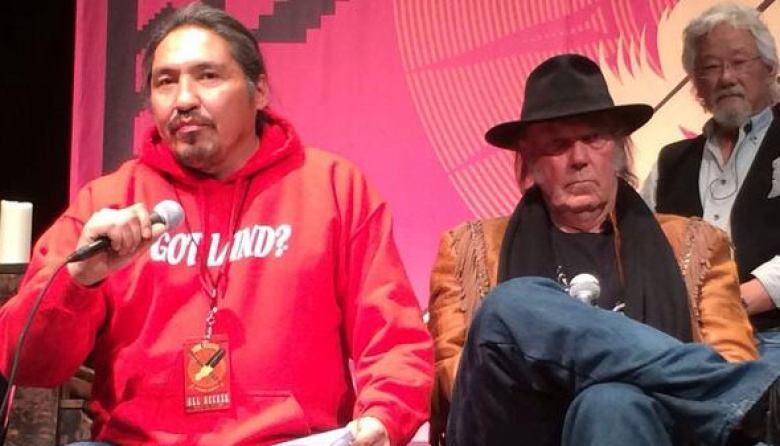

The chief was front and centre when rock star Neil Young and environmentalist David Suzuki embarked on a cross-Canada tour five years ago that raised tens of thousands of dollars for the ACFN's legal fight against the expansion of Shell's Jackpine oilsands project.

The ACFN argued the government's consultation process was inadequate.

In one of several interviews with news media in Toronto before the first concert, Adam said oilsands development had to be stopped.

"When are we going to say, 'Let's get this under control?'"

The Honour the Treaties tour made international headlines, thanks in part to Young’s occasionally over-the-top rhetoric, which included comparing the impact of oilsands development around Fort McMurray to that of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

But the headlines and ticket sales weren't enough to kill the expansion project.

The ACFN's legal challenge was dismissed in late 2014, although the project has yet to be developed.

Fast-forward to today, the same chief who shared the stage with Young as he blasted the oilsands as a "disaster area from war," has signed an agreement in support of the most massive and expensive oilsands mine project ever proposed — to be built in his community's own backyard.

Teck Resources' Frontier project is estimated to cost $20.6 billion, significantly more than any other facility in the region. It would also be the northernmost oilsands operation and cover a territory about half the size of Montreal.

Frontier is designed to produce 260,000 barrels of bitumen per day for an estimated 41 years. The company estimates up to 7,000 workers would be needed during peak construction, and as many as 2,500 people when it's up and running.

Thanks to taxes and oil royalties, the federal government would pocket $12 billion and Alberta would earn $55 billion over the life of the mine.

While the potential benefits are great, so is the potential cost to the environment, wildlife and the traditional way of life of the First Nations and Métis in the region

But what has changed for Adam and other Indigenous leaders here is they no longer see the point in resisting.

"The sad scenario is that I would have loved to fight, and I still love to fight today," Adam said, "but there has to be a time when you have to draw the line and say, 'Yes, you know, we could do this.'"

Fort Chip, as the locals call it, is an isolated town. There is no permanent road linking the northern community of about 900 people to the rest of the province, except for an ice road for a few months every winter.

Most supplies are flown in and residents must catch a flight to Fort McMurray for most services, including to see a doctor or dentist.

The view during that flight brings the enormity of the oilsands operations into clear focus. In the massive mine sites below, machinery digs into the earth and dumps bitumen ore into heavy hauler trucks.

The ACFN and other nearby First Nations have bitterly fought the development of many oilsands projects over the years, but with little success. There has been no stopping the industry’s growth.

In late October, CBC News travelled to Fort Chipewyan for the government's public hearings to find out what the Dene, Cree and Métis think about the proposed Frontier project. The hearings wrapped up in Calgary this month.

The Indigenous people's relationship with the oil industry and government is a complicated battle of wills and conflicting interests that has spanned more than a century. In the communities themselves, there are significant concerns about protecting the environment, culture and treaty rights, set against the allure of jobs, educational opportunities and financial independence.

The relationship is also defined by a lack of trust that any level of government will rein in oilsands development to protect Indigenous interests.

Adam said the real goal of his concert tour with Young back in 2014 wasn't to shut down the oilsands but to highlight how the provincial and federal governments need to stick up for First Nations and their interests in the face of oil development.

Indigenous groups in the Fort Chipewyan region often cite a lack of consultation and negative impacts on treaty rights, culture, wildlife and waterways in their oilsands lawsuits.

However, after so many battles and so many blows, the mindset of the leadership has evolved. They lack the resolve to keep going to war with the oilpatch when there's no reason to believe the outcome will be any different this time around.

Fourteen Indigenous groups have officially endorsed the Frontier project, including Adam and the ACFN, despite their concerns.

"Just because we signed an agreement with Teck doesn’t mean we are in agreement with industry," Adam said.

The Mikisew Cree First Nation (MCFN) is also based in Fort Chipewyan and has signed its support with Teck Resources. Leaders of MCFN and ACFN decided to negotiate deals with the company before the project receives government approval in hopes of being in a better position to sign benefits agreements once Frontier gets the green light.

The agreements with Teck are confidential. However, chiefs say they include some protection for wildlife habitats, water withdrawal restrictions during the Athabasca River's low-flow periods, and opportunities for contracting, employment and a potential stake in the project. The Indigenous leaders who spoke with CBC News said Teck is a good company to work with.

The chiefs hope that one day their communities will achieve financial independence and a higher quality of life.

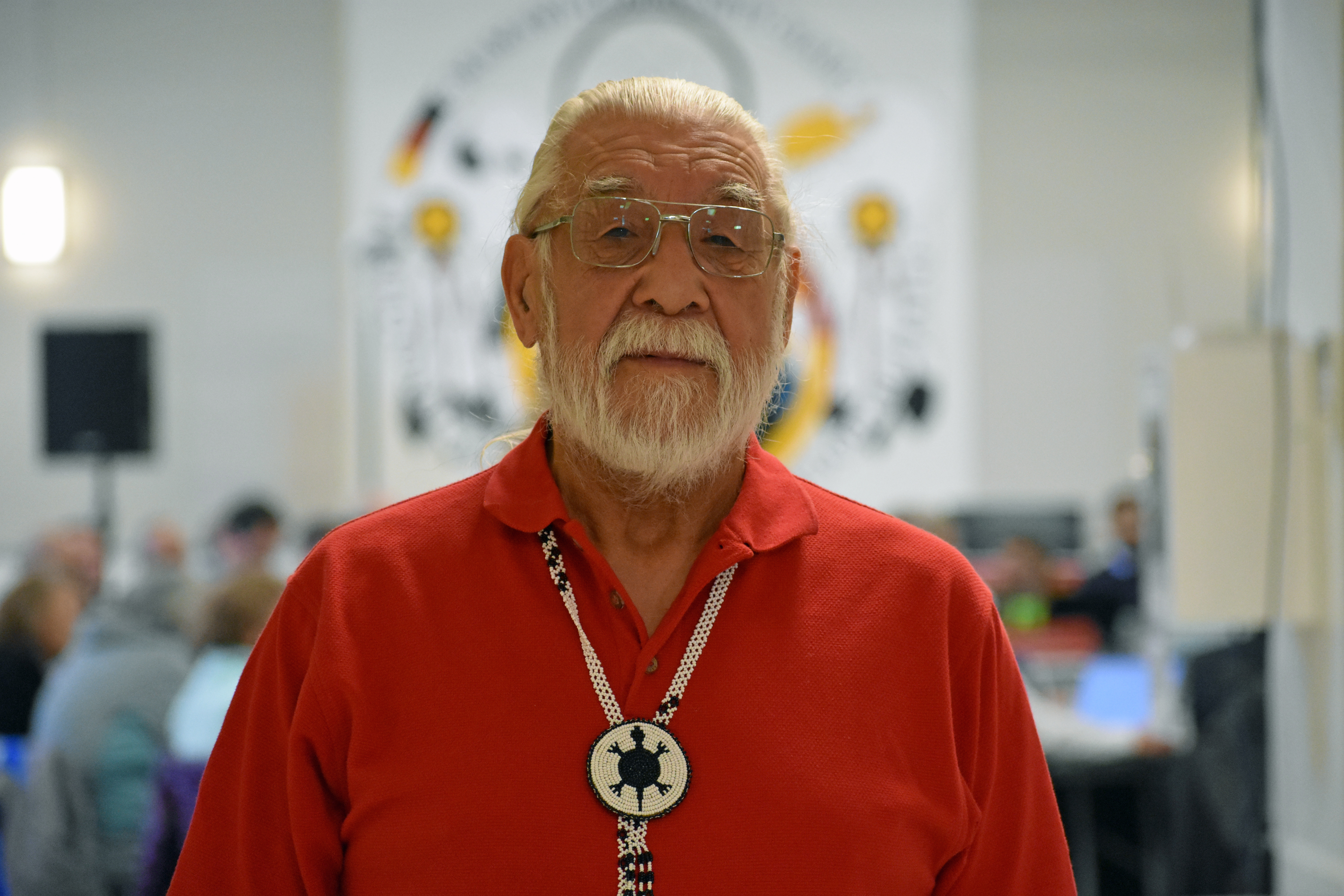

"Myself, as a First Nations chief, I look at the long term," said MCFN Chief Archie Waquan, who also runs the local gas station and convenience store in Fort Chipewyan.

Waquan used to oppose oilsands development. Now, he says working with industry directly is a way to secure environmental protections and other benefits. He said it makes sense to sign a deal with a company while its project is in the proposal phase.

"If I don’t get on that train, then I will be missing out. I never want to chase another train again," he said.

Several Indigenous groups in the region are also actively looking for an ownership stake in the proposed Trans Mountain expansion pipeline, which would ship oilsands crude from Edmonton to the Vancouver area for export. The federal government purchased the proposed project from Kinder Morgan last summer, but it doesn't want to be a long-term owner.

Waquan says MCFN has signed deals with a few oilsands companies operating in the region and is in negotiations with others. He points to the agreement with Suncor for an ownership stake in the East Tank Farm oil storage project as an example of a deal that has benefited his community.

"That is bringing in a lot of funds for our First Nation, where we can at least develop our infrastructures, get our people well educated, hopefully do more business. And hopefully when we do more business, we don't have to rely on federal funds," he said.

"I’d rather we be independent and we get our own coppers from our developments and businesses."

After the government hearings into Frontier wrapped up one afternoon, the chairs were cleared at the local community centre and a meal was served for everyone to enjoy. One of the diners was Jerry Adam, brother of ACFN Chief Allan Adam, and an environmental consultant for a company based in Calgary.

He summed up what he sees as the mood of the community toward the project.

"Let me put it this way," he said. "We can’t stop it. If they are going to develop something here in our land, it's going to happen and we cannot stop it, so we got to go along with them."

The Indigenous people are stubborn, he said, but many have learned there is no point in fighting industry.

"We've argued with oil companies before and we told them, 'OK, we're going to stop you,' but we could never do it."

He wishes oilsands development would slow down, but he's not holding his breath.

"Pretty soon, when you look across the lake here, you’re going to see oil smoke stacks coming up," he said. "I see that in the future."

The list of Indigenous groups that have officially endorsed the Frontier project has grown to 14:

- Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

- Mikisew Cree First Nation

- Fort McKay First Nation

- Fort Chipewyan Métis

- Fort McKay Métis

- Fort McMurray Métis 1935

- Fort McMurray First Nation #468

- Métis Nation of Alberta - Region 1 and its member locals:

- Athabasca Landing Local # 2010

- Buffalo Lake Local # 2002

- Conklin Local # 193

- Lac La Biche Local # 1909

- Owl River Local # 1949

- Willow Lake Local # 780

According to Teck Resources, every Indigenous community in the region that could be affected by the project has signed an agreement with the company.

Still, the Frontier proposal stirs up strong — and often conflicting — reactions among Fort Chipewyan residents. The desire to protect the environment at all costs bumps up against the reality that many people here are employed in the oil industry. The fragile balance between ecology and economics is tricky.

Chief Adam knows there is no consensus.

"There's a double-edged sword to everything I do," he said. "And consequences."

Jean L’Hommecourt grew up in Fort Chipewyan and now lives in Fort McKay, a 45-minute drive north of Fort McMurray. The fact Fort McKay First Nation has also endorsed Frontier brings her to tears.

Government hearings are pointless, she said, because the outcome is always the same — oilsands developers get the green light.

"They're signing agreements with these companies and they're signing our death warrant," she said. "The government doesn’t give a f**k about our people and this hearing is just a gong show."

L’Hommecourt was sent to a residential school at the age of six and stayed there until the facility was shut down when she was 12. She credits her connection to the land and nature for helping her to cope with her pain.

She believes First Nations are making agreements with the oilpatch because they have so little faith in government to defend their interests. Simply put, the communities trust industry more than government.

Wearing a sweater that urges the protection of Mother Earth, L’Hommecourt listed the troubling impacts she says she’s observed over years, including falling water levels, displaced wildlife, dying ducks and birds, and increased health problems in the community.

"I have so many feelings going through me. I'm angry. I'm hurt. I'm emotionally stressed. My health is affected mentally," L'Hommecourt said.

She plans to keep opposing the oilsands for the rest of her life — to try to protect the environment "for the future of our children, for the future of our grandchildren," she said.

At the Keyano College campus in Fort Chipewyan, where the next generation is preparing for their careers, classroom doorways display oilpatch donor logos: Enbridge, Total, Imperial Oil and Shell.

Alex Mercredi-Cardinal, 30, who is studying to become a teacher, said he remembers family car trips as a kid on the winter road to Fort McMurray and how all you could see out the window was trees and bushes. Now, you see sprawling oilsands facilities, one after another.

"It looks very different," he said. "The wildlife have to run through there. They’re losing their home."

Fishermen say fish populations have decreased sharply over the years and some species no longer exist.

Research has found elevated cancer rates in Fort Chipewyan and high levels of heavy metals, such as mercury, and arsenic in animals that are hunted and consumed in the region.

Some in the community are either neutral about Frontier or, like Gerald Gibot, are "in favour of it to a certain point" because it will provide job opportunities for the next generation.

Gibot is a single parent and took out his phone to proudly show pictures of his two sons.

"I wouldn't say I totally support it, but then I got to look at the younger people, not only my kids but all the parents," said Gibot, an MCFN member who was worked in the oilsands.

"With the oil plants here close to Fort Chipewyan, if [the children] choose to go to work at the oil plant, they'll be making their own living. If they choose to live in Fort Chipewyan and hunt and trap, it's up to them."

Rubi Shirley likes to bring out-of-town guests to her brother's property on Allison Bay, a 10-minute drive east of Fort Chipewyan, to show off its beauty. She's a council member with the MCFN and hasn't decided whether she supports Frontier.

"Many people here feed their families with oil. At the same time, it destroys our land and we are very worried about people's health," she said.

Regardless of whether the federal government approves the project, she wants Ottawa to understand the concerns of her community — as a step towards reconciliation.

"Show us results," she said. "Show us that you're supporting our language, our land, our water. That's my answer."

Roy Ladouceur knows every part of the land where Frontier would be developed. His home is just 16 kilometres away from the proposed site.

He is not sure how he would continue his lifestyle of hunting, fishing and trapping if the project goes forward. He is furious that industry continues to expand operations in a region that is already experiencing environmental consequences.

Ladouceur has endured many struggles during his life, including nine years in a residential school.

"I survived alcoholism and a very dark period of my life where I had suicidal thoughts. Now my livelihood will be destroyed. I have to find a way to survive."

He made the 3 ½-hour journey by boat to Fort Chipewyan, snaking up the Athabasca River from his home near Poplar Point, to take part in the government hearings.

Ladouceur wanted to share his grave concerns for the buffalo, caribou and other wildlife in the area, as well as the survival of his way of life, which is directly connected to nature.

"Living off the land, you learn how to respect the land," he said. "You treat it well and it comes around and around. You misuse, misjudge, misdo anything to Mother Nature and Mother Nature will bite you back."

At 70 years old, he's growing tired of the constant strife as the oilsands continue to expand, regardless of opposition from people like him.

"I'm getting to that point," he said. "Sometimes I wonder, 'Am I wasting my time?'"

Watch the mini-documentary by CBC Fort McMurray correspondent David Thurton on the shift in the relationship between Indigenous groups and the oilsands industry.

For now, Frontier's fate remains in the hands of regulators.

The Alberta Energy Regulator and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency have jointly conducted public hearings to assess Frontier’s potential impacts. The review panel is expected to deliver its report in the spring. Then it's up to government to make a decision on the project.

But the ultimate challenge for the project may be economic. Even if Frontier is approved, Teck would still have to make a final investment decision about whether to proceed. Considering Frontier’s hefty price tag and the low price of oil in recent years, some industry experts say there's no guarantee Teck will move forward.

Some experts even question whether any new oilsands mines will ever be built.

For Chief Allan Adam, the battle has spanned more than 25 years. In retrospect, he says, Indigenous communities should taken a stand much earlier.

"It should have started 40 years ago," he said. "Maybe right from Day 1, when the oilsands started coming into the picture."

Like Adam, the community of Fort Chipewyan and its people are on a long journey — one of conflict, heartbreak, compromise and hope — as they navigate the future of development on their ancestral lands.

While environmental and other concerns have not abated, Indigenous groups are increasingly willing to partner with oilsands companies rather than fight the same battles of the past.