July 29, 2018

Each year, when the winds are calm enough, there’s the familiar sight of rowers out on Quidi Vidi Lake, preparing for the Royal St. John’s Regatta.

The oldest organized sporting event in North America takes place the first Wednesday in August, weather permitting, and tens of thousands of spectators flock lakeside for the so-called “largest garden party in the world.”

But that’s not this story.

The lake has a rich history, that goes far beyond that one summer day.

“Quidi Vidi has always been an integral part of life in St. John’s,” said Larry Dohey, the director of programming and public engagement at The Rooms.

Dohey says while the regatta may be the first thing that comes to mind when talking about Quidi Vidi Lake, its influence goes far beyond. The area has always been a popular destination.

“We're not the first people to use the lake as a place of leisure or relaxation; go for a run, go for a walk — that has been [happening] since St. John's has been here, really,” he said.

These are the other stories from the lake’s shores — the stories you probably DIDN’T know about Quidi Vidi.

The parties and music

The north shore of Quidi Vidi Lake is known for its deep military roots, but — to this day — it’s also the place for some wild parties and epic musical performances.

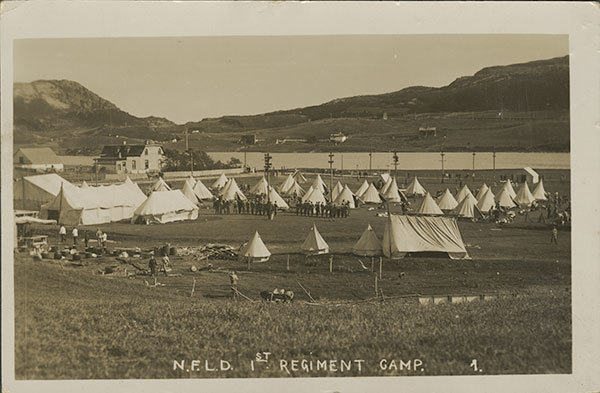

It all started during the First World War, when the Newfoundland Regiment set up training camps in the area. The troops worked hard, and they played hard, with what were called "smoking parties" held in the tents.

"A smoking party is a bunch of men gathering and drinking," explained Dohey.

"It comes out of an old English tradition where they would gather in very fine rooms and they would smoke and discuss philosophy. But … these men would gather under tents and it was really all about the drinking and all about the dancing and all about the music."

Nowadays, the modern equivalent are the Iceberg Alley concerts.

"These tents are put up and essentially on the same location and for the same purpose!" Dohey said.

The party atmosphere continued into the Second World War, when the United States set up its Fort Pepperrell base (designed in the shape of a cowboy hat) in Pleasantville.

Newfoundland guitarist Sandy Morris said the base had its own military band — directed by legendary film composer John Williams before he hit it big in Hollywood — and the locals developed close ties with the American soldiers.

The military would also bring in musical acts to play the officers’ mess.

"You'd have all sorts of stars ... Everybody you could think of, basically," Morris said, including Frank Sinatra.

"Local bands would play there, and they would have their own combos that would play there. And it was a huge place, and musicians loved to play there, because the beer was so cheap — 25 cents a beer."

The soldiers would watch the Newfoundland groups and suggest records — and clothes — that they should order.

"I remember distinctly when we were growing up, we were always poisoned that our T-shirt necks didn't come up as far as the American T-shirt necks did, because they looked better,” Morris recalled.

“We used to turn our T-shirts around backwards, so we'd get a higher neck on them."

Pepperrell also had its own radio station, called VOUS, which Morris says would play music unlike anything Newfoundlanders had heard before: R&B, deep country, and jazz; acts like James Brown, Buddy Guy, and B.B. King.

“I couldn't believe what I was hearing," Morris recalled.

"I think the first time I ever felt high, a natural high from listening to music, was listening to Booker T. and the MGs on VOUS. It captivated me. And it still does to this day."

The Newfoundland and American musicians eventually started jamming together. Morris said he played in a band called The Ambassadors with Tony Gaines, a professional singer from New York City.

"When he got out of the service, he moved back here so he could stay with the band — and that became the Garrison Hill, which at the time was the hugest band on the island," Morris said.

That American influence stayed with Morris, and can still be heard in his music today — including on a recent album he released with Anita Best.

"Some of the way I play those Newfoundland songs are directly influenced by the R&B that I heard as a kid, no question about it," he said.

"I tried to find grooves to put underneath the Newfoundland tunes."

The hotel

Tales of parties on the north shore started well before the Great War.

Back in the 1800s, anyone who was anyone had to be seen at the Royal Lake Pavilion on Quidi Vidi Lake.

It was known as a “roadhouse,” an elaborate building with a restaurant and rooms, which was owned by an eccentric man by the name of Professor Charles Danielle.

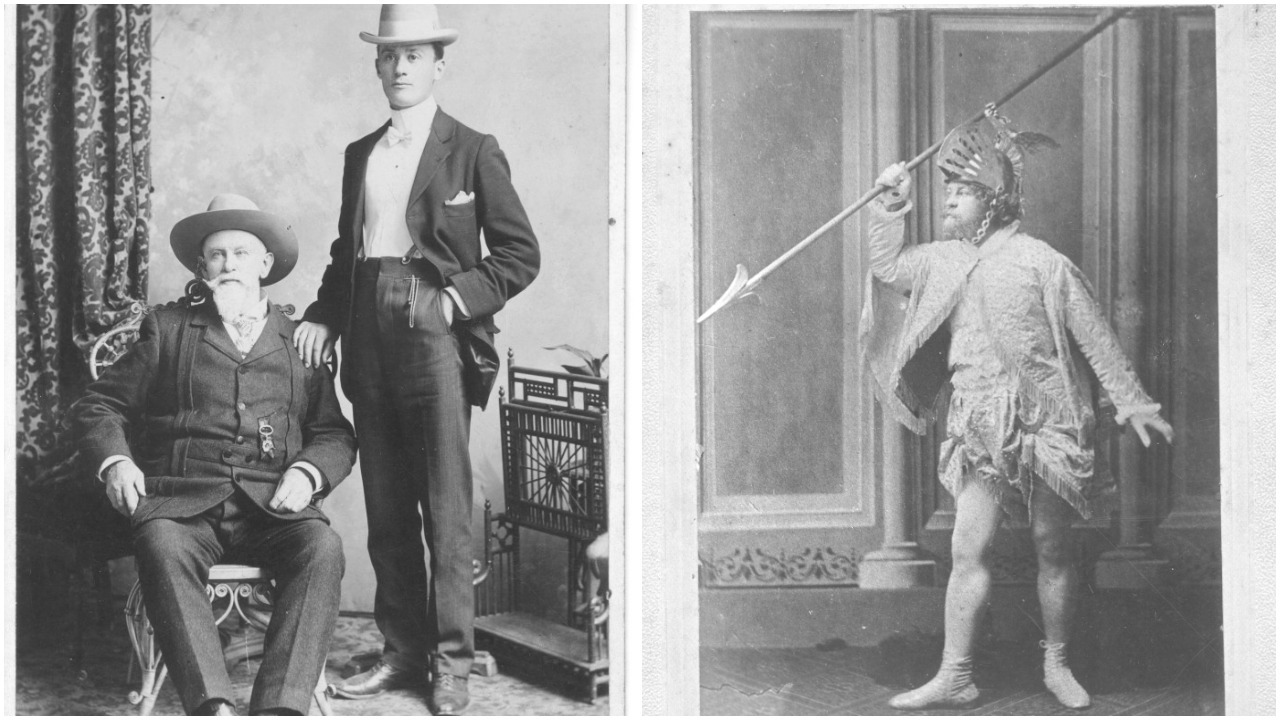

Born in Maryland in the 1830s, Danielle mysteriously showed up on the shores of St. John's some 30 years later. He was a visionary, with a penchant for elegance and large, lavish displays.

"In the parlance of the day, Charles Danielle would be described as a big personality," said Dohey. "He's a real entrepreneur. He's a dance teacher, he's a restauranteur; he's someone really engaged with the whole community."

Dohey says the Royal Lake Pavillion was a beautiful building, built on farmland on the outskirts of St. John’s, that was quite popular.

"This was elaborately dressed with all kinds of oriental design and drapes and [was] really quite elegant,” he said. “And that's where you would want to go if you were of any means in St. John's."

Danielle was renting the land from farmer Joseph Ross but Hilda Chalk Murray — an author who has written about farmland in Newfoundland and Labrador — said the two didn’t get along.

“I don't think people knew quite what to make of him."

“He wanted everything elegant and just so. If you're working with cows all day out on the field, that's rather foreign,” she said.

Murray said the farmer wanted to increase Danielle’s rent.

"Ross said that he was getting rent of $12 a year ... and he said that wasn't enough to keep two goats alive!" she said.

Dohey said Danielle was not too pleased with the news, and so he took down the roadhouse, board by board, and moved it to Paradise.

"He carted it by horse and cart to the railway station, and took I think it was two car loads by train, took it out to what was called then Irving Station, which is now in Paradise. And built his Royal Octagon [Castle] ... on the side of the lake, which now takes the name Octagon Pond," Murray said.

The Octagon Castle, named for its shape, was another substantial building, and everyone wanted to go there.

"If you were going to go for a fine dinner or for accommodations, [back] in the day, they used to refer to it as an 'excursion.' So you would go out to an excursion around the bay; you would go to [Paradise]," said Dohey.

Danielle was always thinking outside the box — or about the box, in this case. He designed his own casket, with a glass top, that he put on display in a room at the Octagon Castle.

"He was always pretty keen on doing something that might be unique, to bring the crowd," said Dohey.

"The idea was: 'That'll get the conversation going in St. John's. The crowd will want to come out and see this.'"

Danielle passed away in 1902, and he was as extravagant in death as he was in life.

The professor was specific in his instructions for his funeral. His casket was put on a train, and brought into St. John's, where about 30,000 people — most of the city’s residents — lined the streets to catch one last glimpse of him during the procession.

"They saw the passing of a significant person ... He did influence the culture and the heritage of the place."

His final resting place is across the lake from his first hotel, in the Anglican Cemetery on Forest Road, where his headstone still stands today.

The cemeteries

The Anglican cemetery is one of two graveyards on the shores of Quidi Vidi Lake, which were established in 1849.

Prior to that, interments were located within St. John’s, including at the Roman Catholic cemetery on Long's Hill, which opened in 1811, and the Belvedere cemetery on Newtown Road, which was the "merchant cemetery," where well-to-do families were buried.

But after a fire ravaged the city in 1846, a typhoid epidemic broke out.

"Everyone living in the town were convinced that the cause of this epidemic ... was because as the bodies deteriorated in the cemetery, the residue was going into the well water," Dohey said.

That's when government decided it would close cemeteries in the city's core, and establish two graveyards on the outskirts. The Anglican Cemetery had a mix of ornate and simple headstones, while Mount Carmel Roman Catholic Cemetery, off the Boulevard on the other side of the lake, was considered "the fishermen’s graveyard,” where the poor were buried.

Some of the graves from the Roman Catholic cemetery were then moved to these two graveyards — which is why two graves in the Mount Carmel cemetery pre-date the cemetery itself.

Meanwhile, the Irish part of the old Long’s Hill graveyard is now the "forgotten cemetery," buried underneath the asphalt of the St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church parking lot (The Kirk).

Unusual sports

Between the two cemeteries that stand on opposite hills is the head of Quidi Vidi Lake, and an area that’s known for sports.

While rowing might reign supreme on the lake these days, other popular sports used to be held there.

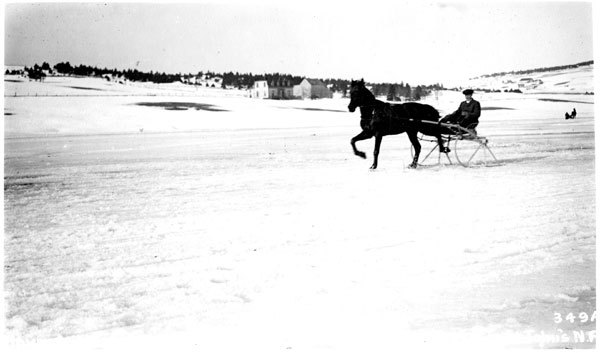

The oldest reference to sport in Newfoundland and Labrador is an account in the late 1700s of horse-drawn sleighs racing on the frozen lake. The sport, also called “tilting” and “ice racing,” continued into the 1940s.

Two other interesting games that took place at the Regatta involved grease.

In the greasy pole contest, people would test their balance as they tried to walk along a greasy pole, placed over the edge of the lake. If they made it to the end without falling into the water, they would find their prize: a bag of flour, cash, clothing, or a ham.

People would also try their hand at capturing a greasy pig.

Johnny Burke, the Bard of Prescott Street, wrote about the greasy pig contest at the Regatta in 1912.

"But to add to the difficulty of retaining him, he was carefully greased all over the body and legs. At a given signal he was released, and was the prize of any who could capture him,” Burke wrote.

“Squealing as only a pig can, he rushed through the crowds who would try to capture; being no respecter of persons, he would bowl over men, women and children.”

The prison

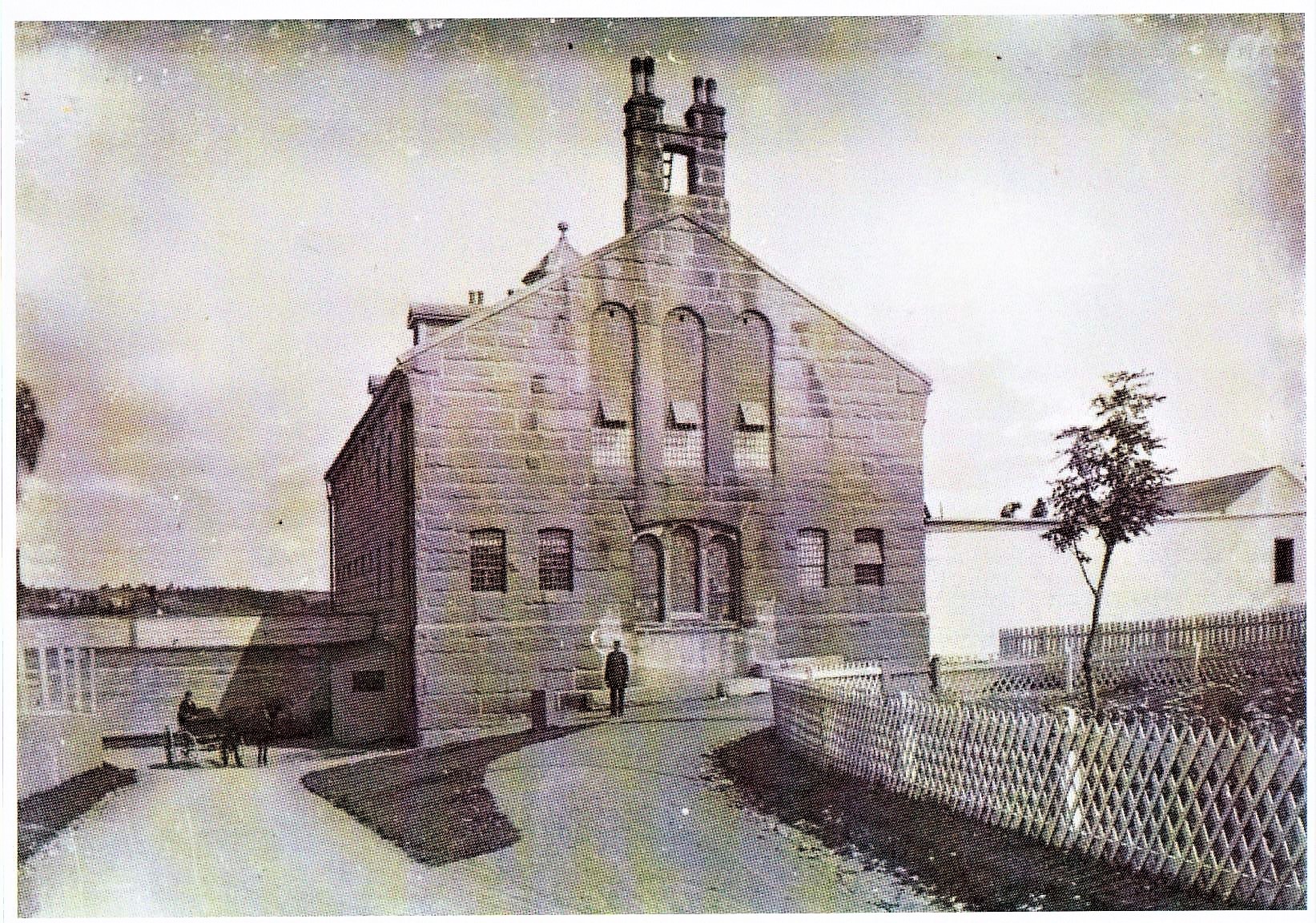

Standing in stark contrast to the revelry of Regatta Day, on the south side of the lake, is a cold, foreboding building.

Her Majesty’s Penitentiary is one of the oldest stone buildings in St. John’s — and still in use today.

Construction was originally set to begin on HMP in 1852.

The plan was to build the facility outside city limits, because no one wanted a prison in their backyard. But it was put on hold, due to financial constraints.

"There was a lot of materials already purchased and there was a lot of stone shipped over from Ireland to build the prison. So what they did, they auctioned off a lot of the materials that they had here," said David Harvey, a retired captain of HMP.

"The RC Episcopal Corporation ... bought up all the materials and they built the present day St. Bon's College. So if you ever drive by [it] on Bonaventure Avenue, you can look in and say, 'That was the stone originally meant for the prison here.'"

Her Majesty's Penitentiary was finally opened in 1859, and currently houses almost 200 inmates.

Gradually, other people started moving into the area of the lake, which became known as Hoylestown. It was a working-class neighbourhood, until the upper-classes moved into the Forest Road area in the 1890s.

Prison break

There was excitement in Hoylestown around that time, when a prisoner escaped from HMP.

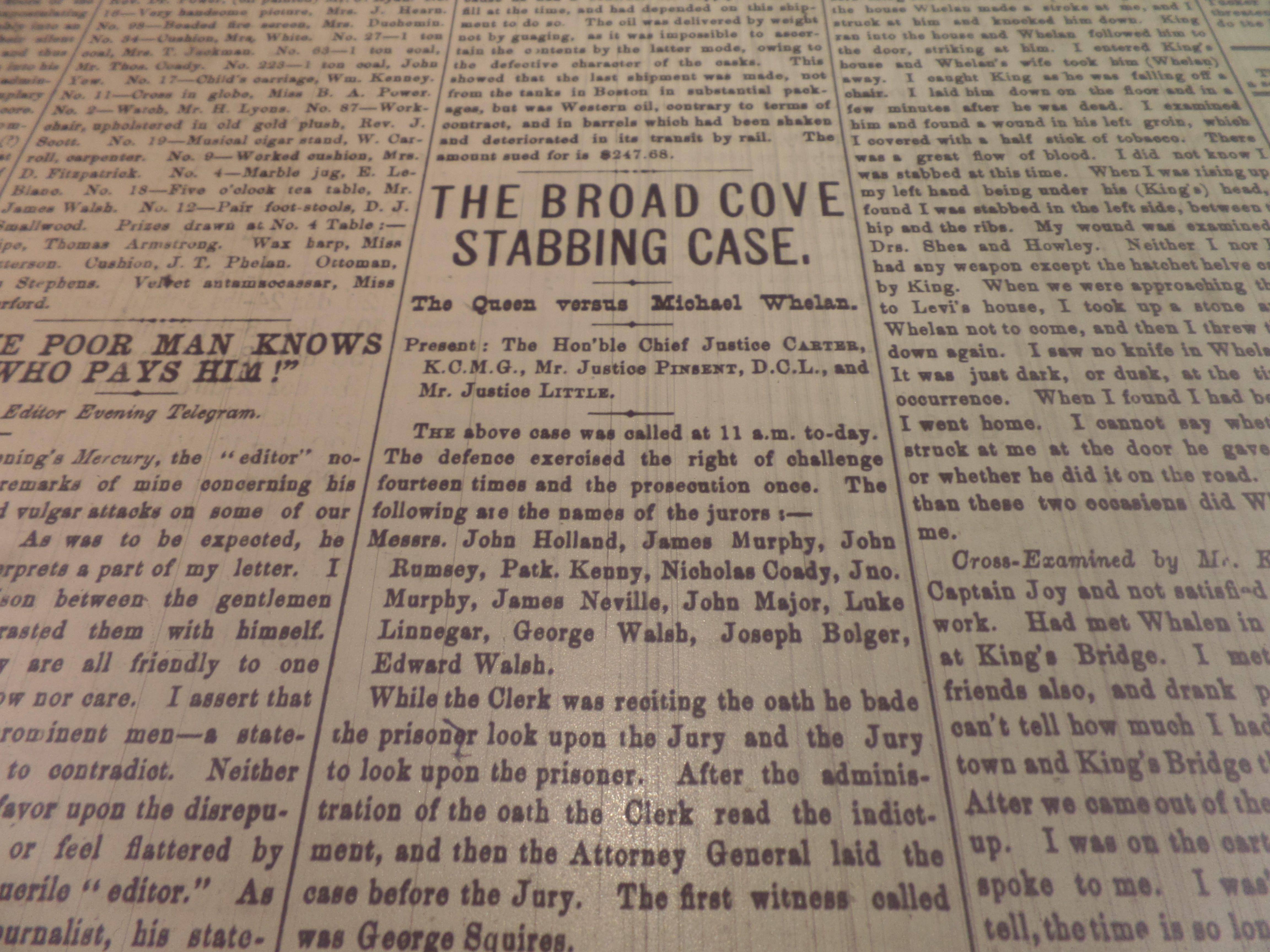

In 1883, Michael Whelan, originally of Horse Cove (which is now St. Thomas), was convicted of killing Levi King of Broad Cove. After spending four years in jail, Dohey says, Whelan had developed the reputation of being a good prisoner — so he was placed on work detail.

"One day ... they're working over by the old General Hospital on Forest Road, and they're digging away at a trench," Dohey recounts.

"And he excuses himself because he has some 'private business' to do. And so he walks away from the guards and the work crew, behind a tree, and he looks back and sees an occasion. So he starts to run."

It's said that Whelan ran around the lake, with the prison guards chasing him — but he was fast, and he ran right into the White Hills.

"Which is pretty ironic now, because if you run into the White Hills ... you're running towards the RCMP headquarters," Dohey said.

Whelan is the only escaped prisoner from HMP to never be see again on the island.

"The last time we heard anything about him was in 1905. We know that there's a Michael Whelan living in Boston, and we're pretty certain that he did move to the United States," Dohey said.

"His wife eventually left Newfoundland — and rumour has it she left to go join her husband, who had escaped from Her Majesty's Penitentiary."

The church

When Michael Whelan made his escape, he may have passed by Quidi Vidi Village, a small fishing village with a protected harbour that’s tucked away behind a hill at the far end of the lake’s east side.

One of the most iconic buildings along the narrow main road is an old Anglican church. It was featured in the final scenes of The Viking in 1931 — the first Canadian feature film to record sound and dialogue on location.

Now, it’s where Aiden and Pinky Duff call home.

That act of converting the old church into a functioning house marked the beginning of the heritage movement in Newfoundland and Labrador.

"It was in the '60s, and the church was no longer in use, and the Anglican Church was going to tear it down. And there was a group that got together: Shane O'Dea, and Shannie Duff, amongst others, and they put together a group they called the Newfoundland Historic Trust," Aiden Duff recalled.

"They were the owners, and they decided they didn't want to be into property management anymore, and they asked me was I interested in buying it."

It took a lot of hard work, time, and money to make it into a dwelling, but Duff says it was a fun project, and he’ll never part with it. He says the building was pretty rough and wide open when they took ownership, with the pews and altar already taken out.

Duff says he’s required to maintain the unique features, like the church windows and curved mouldings. But he says the building also has its own quirks, including an inscription on the arch in what is now his living room.

"That was underneath plywood when we moved in. We didn't know it was there 'til we took the plywood off and found it," Duff said. "My wife got up on a scaffold and spent ... a week with an artist brush painting around the gold letterings."

If you look further up, towards the ceiling, there are two large, interlocking hooks.

"They hold the two ends of the building in. They basically perform as the bottom chord of a truss," Duff said.

"It's just bent and twisted. But you know, it's an old building. It was built in 1842 ... When we're that old, we'll be bent and twisted as well."

The ceiling also has its own story.

"Someone told me that the Americans put that up, when they were blasting over here, they put a few rocks through the roof, and to compensate, they fixed the roof, and put a new ceiling in," he said. "I don't know if it's true or not. It's a good story though!"

Duff said the neighbourhood has changed a lot since he first moved in. He says there are more businesses setting up shop, like Mallard Cottage and Quidi Vidi Brewery.

"There's a few extra houses here now — bigger houses ... That's the biggest change. And people wanting to move here now,” he said. “When we moved here, it wasn't a popular spot. Now, everyone wants to be in Quidi Vidi.”

Development and “shebeens”

The issue of development in Quidi Vidi can be traced back to complaints being made in the 1890s.

At that time, many little trails started popping up from St. John’s towards the lake — and so did some shoddy structures. They became known as "shebeens," an Irish term meaning shady, unlicensed establishments that sold alcohol.

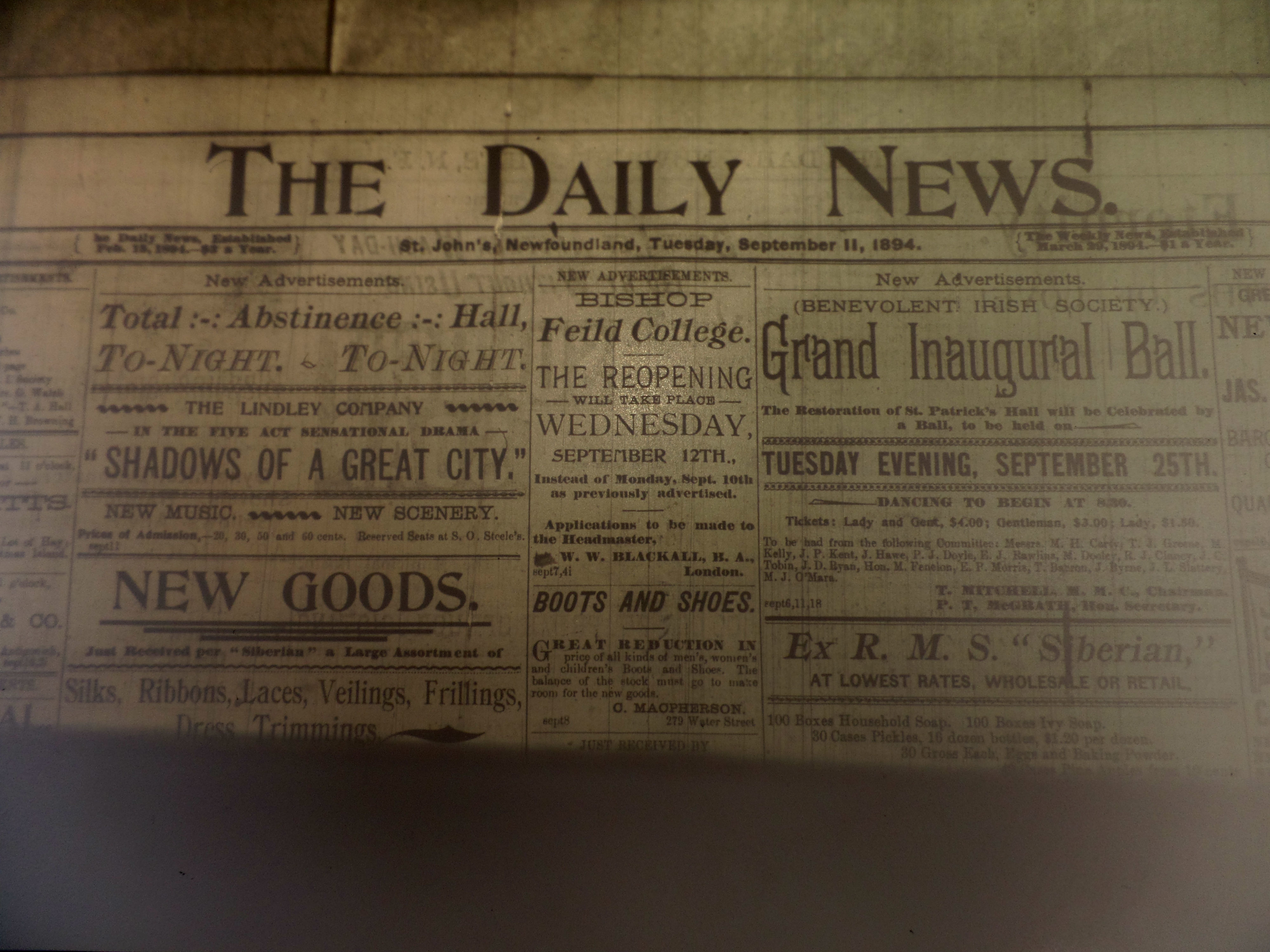

In 1894, there was a letter to the editor printed in the Daily News, complaining bitterly about the drinking going on in these places.

"And he ends off the letter by saying, 'You know, everything is gone to hell in a handbasket. Start thinking about that beautiful lake. The next thing you know, what's going to happen down there, there's going to be a ... slaughterhouse,'" Dohey recounted.

"And of course if you go around the lake nowadays, there is a chicken slaughterhouse."

Development did become front of mind for Newfoundland Prime Minister Edward Morris in the early 1900s.

Dohey said Morris had heard that the farmers along the north shore of the lake were being approached by private developers, so that they could build a new subdivision.

"He realized that if these people sold these properties to private individuals or to corporations... then the people of the town would not have access to the lake," Dohey said.

"So he rallied with some friends of his and he raised the equivalent nowadays of about $500,000 and he approached the 15 farm families that owned and had titles to the land, and he purchased the land so that he could secure this place as the site for the Regatta."

The lake today

And now, thanks to Edward Morris, we’re set to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Royal St. John's Regatta, and the public enjoyment of the lake continues.

The people and the area may have changed, but the one constant is the lake itself — a place where people, to this day, still come together.

“Quidi Vidi was always a place to come to, or gather, or go for a leisurely walk … a place to come to for sports…. We come to regatta every year,” Dohey said.

“So it's history constantly repeating itself.”