February 8, 2021

Two days are especially vivid in Felix Ndayitwayeko's memories of Fredericton.

The first is the day he arrived, excited and hopeful about a new life after years in a refugee camp.

The second is the day he was chased outside his home by men with bats.

The Burundi-born Ndayitwayeko was pulling up to his home on Fredericton’s north side when he looked at his rearview mirror and saw masked men chasing his car.

He had been visiting his sister, and it was almost midnight on a weeknight when he parked on Wilson Row, a cul-de-sac off Doone Street.

It was as if they’d been waiting for him. As he got out of his car, two white men threw rocks, eggs and sticks at him while spitting racist slurs.

“They started calling me the N-word, like, ‘We’re going to kill you, we’re going to send you back to your country,’” said Ndayitwayeko.

He was living in subsidized housing built 50 years ago along Doone Street and Wilson Row, a neighbourhood of 64 townhouses, with small windows, and green, tan and brown siding.

From Doone Street’s start, crime and street fights seemed common.

But for decades, tenants had someone to turn to for help. They also found — through programs offered by the New Brunswick government — help getting out of poverty.

Today, however, many tenants of Doone Street are immigrants, the government has abandoned its active helping role, and the newcomers have had to confront an additional problem: racism.

Some families fear their own neighbours.

‘I didn’t even know if they had different weapons on them.’

That October night in 2017, the rocks didn’t frighten Ndayitwayeko. But when the baseball bats came out, he was just a few steps from home. He ran in the opposite direction.

“I wanted to go and hide inside, but my fear was that I had my parents inside and my youngest siblings,” said the 23-year-old.

“I didn’t even know if they had different weapons on them, a gun or something. So if I ran into the house and they catch me before I lock the door, or they break into the house, that would have been a different story.”

As he tried to hide from the men chasing him, Ndayitwayeko called the police.

They arrived about 30 minutes later, according to Owanjema Ahuka, Ndayitwayeko’s neighbour, who witnessed what happened.

After hearing screams, Ahuka, 22, came out of his house and was almost hit in the face with a bat. Things settled down after police got there.

“They just told us, ‘Go back in your house. We fixed things up,’" said Ahuka, who was born in Congo but grew up in Burundi. “And we saw the people that were fighting us, they were walking away.”

Two days later, Ndayitwayeko, who’d spent half his life in a refugee camp in Tanzania, saw police moving his assailants out of Doone Street.

Nobody was charged, he said.

Insp. Kim Quartermain, in charge of the Fredericton Police patrol division, called such a removal of tenants an intervention but said she cannot speak to specific investigations.

“Not that displacement is always the answer, but sometimes that’s a tool that is used in a small community, if we are calling the Doone Street area a community.”

Racist incidents in an area of public housing known as Doone Street in Fredericton have left some immigrants fearful of their own neighbours.

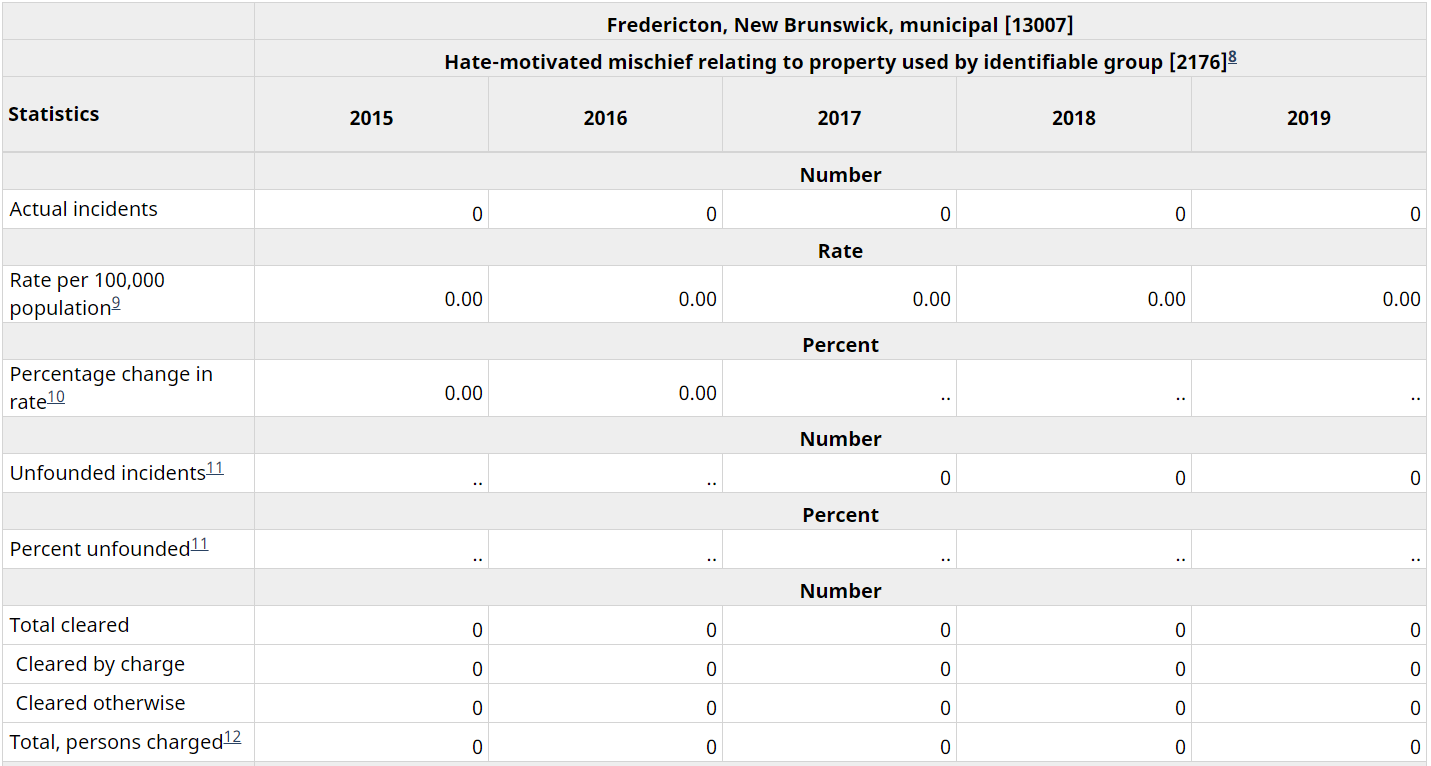

Fredericton police are required by Statistics Canada to track the number of hate crimes, but from 2015 to 2021, none have been recorded.

In 2019, Fredericton police said they investigated 12 cases where hate was the suspected motive. Half caused property damage, and no charges were laid.

No charges were laid in 2017 or 2018 either, when a hate-based motivation was investigated twice each year, according to police.

More victims

On New Year’s Day in 2019, Ahuka’s family was attacked on Doone Street.

Ahuka, his sister and his mother were coming back from the hospital with his 85-year-old father, who had been treated for high blood pressure.

It was around 4:30 a.m. and Ahuka, who was driving, stopped for a man crossing the street after coming out of a Doone Street unit.

“I thought he was just going to pass, but I just saw the guy coming to my car and then start, like, hitting the car, punching the windshield,” he said.

Ahuka didn’t know if the man was armed, so he stayed inside the car with his family.

The man ran back into the townhouse.

Ahuka reported the incident to police, who later told him the man didn’t live in the area.

Ahuka never heard if he was charged.

Ahuka has since moved across the St. John River, and Ndayitwayeko moved to Hamilton, Ont., where he has three jobs and lives in a tiny apartment.

Their families still live in the old neighbourhood.

Every day, Ndayitwayeko said, he fears for his parents and five siblings.

Stuck at Doone

News stories about Doone Street from the late 1970s say police cars responded to tenant calls almost daily.

A councillor characterized the area as a blot of rowdiness “progressing to the stage of gang warfare.” A government housing official said in areas like Doone Street there’s “no way to avoid all the bad apples.”

But in recent years, the makeup of the neighbourhood has changed, especially with the influx of immigrants in Fredericton starting in 2012 and 2013 — from Syria, Congo, and Burundi, among other countries. The worries of Doone Street tenants, many of them newcomers, increased.

Complaints about racist attacks in the area became regular, according to Marisa Rojas, a social worker at the Multicultural Association of Fredericton.

There was a consistent theme among the complaints to the association. Some Doone Street residents were targeting newcomer families and harassing them into leaving, she said.

“They do things that you probably don't want to hear the stories about,” said Rojas.

When tenants reach out to Rojas at the Multicultural Association, she helps by calling the police and Social Development.

But Rojas, who lived on Doone Street from 2004 to 2007, said there’s not much she can do about the government’s decision to cut the community involvement co-ordinator who did so much to get her and her two kids out of poverty and out of Doone Street.

“Programs to promote, to help, to support, are not in place. So the people now are stuck there.”

A Social Development official said the department doesn’t track the number of immigrants in social housing.

‘They want to send us back'

Meryem Najiya moved to Canada in February 2016 with her kids, Huseyin, 15, and Ghazal, 9.

When a bomb detonated near their home in Syria and killed her husband, Najiya and her kids went to a refugee camp in Turkey.

A few months later they got an offer to move to Canada.

During their first few months in Fredericton, the family lived in an apartment in Boyne Court and in December 2017, moved to Wilson Row, across the street from Ndayitwayeko.

Najiya, although grateful for the kindness shown by other Canadians since her arrival, said she hasn’t received a call or a visit from the Department of Social Development since she moved to the neighbourhood.

“Nobody [from the department] checks up on how I’m doing here or how the situation is,” Najiya said, with her daughter Ghazal acting as interpreter.

“Sometimes I find in my mailbox, like a card or invite to go for a turkey dinner or barbecue, but because I don't understand [English,] I don't go.”

In fact, Najiya and her children stay home as much as they can because Ghazal and Huseyin were bullied whenever they tried to play outside.

Older children would walk up to Ghazal and her brother when they played soccer in front of their townhouse or in a nearby field.

“They say, like, they want to send us back to our country,” Ghazal said. They say bad words. That makes us feel bad.”

“And sad,” added her mother.

Najiya attends daily online English classes hosted by the Multicultural Association and is looking for a job.

“If my children, they need to go to play, I go to a different area, like to the park, to the lake, something that is far away from here.”

She said she was told by Social Development before moving to Doone Street that she could live here for as long as she needed to, but Najiya, who earned money as a seamstress in Syria, said she will leave as soon as she is financially able.

Coming out of poverty

Life at Doone Street for Rojas was very different.

She left Colombia in 2000 and came to Fredericton with her two sons to escape the guerrilla movements in her country.

In 2004, Rojas got a call from Social Development, offering her a unit at Doone Street.

When she told her kids about it, “they said this neighbourhood has a really bad reputation” and asked their mother not to take it.

But she did. Tenants in public housing in New Brunswick pay roughly 30 per cent of their household income for rent. Rojas was determined to save her money to buy a home.

Unlike Najiya and Ndayitwayeko, when Rojas signed her first lease at Doone Street, she was told by Social Development officers that they would help her move out of subsidized housing as soon as possible.

“And they did.”

Rojas said courses on how to save money and manage finances were always available to the community.

Ndayitwayeko, Najiya and Ahuka had never heard of these opportunities.

Rojas is still grateful for a program called Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition.

It was an eight-week course offered by Social Development where tenants learned how to identify their marketable skills and gain confidence, so they could find work.

“They would give feedback on the skills you were using every day and helped you see yourself in a different, more valuable way.”

Police, meanwhile, were on Doone Street once or twice every week, following up on reported incidents, Rojas said.

A Social Development community involvement co-ordinator was there too.

“The government used to have this person that was in charge of the community and was always there,” Rojas said. “If someone was misbehaving, doing big conflict or partying late in the evening, they would be called."

Programs cut

Rojas thinks life for Doone Street tenants has become more difficult because the programs that helped her have disappeared.

Tammy McMaster, who has lived on Doone Street for 17 years, agreed. Ever since the community involvement co-ordinator position was taken away more than 10 years ago, “things gradually fell.”

“I don't think the government really sees it,” McMaster said. “It helped people.

“We used to have a hot-lunch program, bingos, summer programs for the kids. There used to be an adult learning centre in the community building.”

Asked about Social Development’s responsibility for helping newcomers feel safe in social housing, Minister Bruce Fitch said, “That is a broader role for the community.”

He said the role of the community involvement co-ordinator was redefined in a “broader” way, and the person in that job is now called a program officer.

Fitch suggested CBC News talk to a program officer, but his department would not allow this.

McMaster said the community involvement co-ordinator would go to different public housing areas in Fredericton and help the tenants association in each. Doone Street’s association has not been active lately.

A program officer is more like a landlord, enforcing and signing leases, making sure people are doing what they’re doing in the community,” she said.

McMaster said program officers sometimes come to the area but have many other things on their plate.

“Creating programs for the community — that’s a small percentage of their job. When we had the community involvement co-ordinator, they worked a lot more in the community. We saw them all the time, I could call her. Now, it has changed.”

No programs have been available since the co-ordinator position was dropped.

“We don't have anything,” McMaster said. “Language barriers can be a thing. It’s also a lack of interest. No one wants to volunteer.”

'It's not enough'

Rojas said the Multicultural Association has a community support system available to immigrant families on Doone Street.

But they are treating symptoms, not the cause, and this, she said, is not enough.

“That, in my opinion, is where the main problem is. If the people are not integrated and the people have nothing to do and the people have no support, then what will the people do?”

Giving up on New Brunswick

March 13, 2015. Ndayitwayeko remembers the exact day that he landed in Fredericton with his family.

He remembers the excitement he felt, he remembers the snow, he remembers thinking how, after living in a refugee camp in Tanzania for years, everything was, finally, going to be good.

“I was 17 and excited to be in a new place and make new friends.”

But Ndayitwayeko also remembers running from the two men with bats, while his siblings stared through the windows of their home and screamed.

All he could think of was protecting his family.

In Hamilton, Ndayitwayeko works 90 hours a week at the Toronto and Hamilton airports, and he has no plan to return to New Brunswick.

“I feel like the system there, it was not meant for us,” he said.

“I’m trying to find a safe neighbourhood in Hamilton for my family to eventually move to.”

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.